April 1968, somewhere in New York City. Alexander ‘Skip’ Spence, mercurial genius of San Francisco five-piece Moby Grape, has flipped. Sweating like a madman, his hair is tufted at wild angles, his once-trim beard looks for all the world like it’s just been savaged by a hatchet. He’s just ripped chunks from the door of bandmate Don Stevenson’s room back at the Albert Hotel, where the porter is left gibbering about a crazy man wielding an axe. Steeped in LSD and the occult, the crazy man believes Stevenson and fellow Grape Jerry Miller are evil and must be destroyed. Right now, axe in hand, he’s following their trail to Columbia Studios on 30th Street. In a taxi. In his pyjamas.

In truth, the damage had already been done. Moby Grape had begun to splinter long before Stevenson’s hotel door was splintered. American rock’s Next Great Hopes were in chaos. Police arrests, record company hysteria, aborted tours, wretched luck and managerial conflicts had all played their part. In fewer than two years, Moby Grape had gone from golden child to diseased waif.

“I actually feel kinda blessed,” Jerry Miller says today, his words heavy with irony. “It’s such a unique distinction to have messed up everything. We had our stuff together pretty much, but then a lot of things just fell apart along the way.” Stevenson agrees: “It was a huge missed opportunity. It’s just too bad there wasn’t somebody around who had our best interests at heart. We needed someone to bring the best out of us, rather than take us into a back room and chop us up into little pieces for publishing rights.”

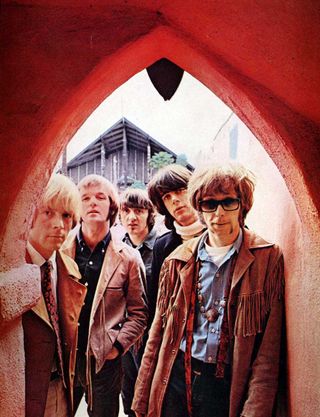

In many ways Moby Grape’s story is similar to that of a thousand other West Coast bands who fluttered briefly then flopped. Except that the Grape were real contenders. With an embarrassment of riches – five members who could all write, sing and play – they were touted as the Bay Area’s own wet dream team: as scorched as the Stones, dreamy as the Byrds and soulful as Hendrix. Seven major labels were jostling to snap them up by the end of 1966, including Elektra, Atlantic and Columbia. But they still blew it, trapped in a contractual mêlée that haunts them to this day.

Only now, 40 years on, have they achieved closure with ex-manager Matthew Katz. Lesser people would have given up, but the Grape fought on. The four remaining members – Miller, Stevenson, Peter Lewis and Bob Mosley (Spence died in 1999) – have all shared this marathon struggle, bound by a belief in some kind of legal and karmic justice. They wanted what was rightfully theirs.

“There may be some redemption to all this,” Lewis offers today. “For us it’s not really over. Everybody has to accept responsibility for what happened. It doesn’t do good to go through all that and learn nothing. Some of us paid a heavy price, Skippy especially.”

It had all started so brightly. Before heading for San Francisco in 1964, Miller, from Tacoma, and Seattle drummer Stevenson had cut their teeth on the hip bar scene of Washington’s Pacific Northwest, alongside garage legends like the Sonics and the Wailers. Guitarist Miller had toured with Bobby ‘I Fought The Law’ Fuller and crossed paths with a young Jimi Hendrix.

Stevenson had held the beat for blues shouters like Etta James and Big Mama Thornton. “When we left for ’Frisco,” Stevenson explains, “it felt like we were off to the promised land.” For their band the Frantics they soon recruited tough San Diego R&B man Bob Mosley, from the Misfits.

“I thought he was the coolest thing I’d ever seen in my life,” says Stevenson. “Bob was like some surf god. He had this beautiful energy about him, was about as macho as you could get. And he sang better than any black guy I’d ever seen.”

It was short-lived, though. While Miller and Stevenson formed Marsh Gas, Mosley quit for LA, hooking up with future Flying Burrito Brother Joel Scott Hill and Peter Lewis, the brooding son of 40s film actress Loretta Young.

Then they met Jefferson Airplane’s ex-manager Matthew Katz. “Katz said for Pete and I to come up to San Francisco and start a band,” Mosley recalls. “So we did that, and got a hold of Jerry and Don, told them that Katz had this amazing guy from Jefferson Airplane, Skip Spence.” Canadian-born Spence – a one-man tornado – had briefly played in Quicksilver Messenger Service, then been the drummer on Jefferson Airplane Takes Off.

In August ’66, just as ’Frisco began its acid bloom, Moby Grape was born. “San Francisco was really something then,” Miller remembers. “It was just beautiful to People would come over from the Avalon and the Fillmore. I’d look out from the stage and get freaked. It was like playing music to a buffalo herd. There were a lot of really strange people. The thing was to play 20-minute songs, but we were doing original four minute pop gems.

“It was incredible, because we’d be playing there with Lee Michaels, Janis Joplin, Buffalo Springfield and the Grateful Dead. A lot of people nobody had heard of that were just about ready to explode. There was some awesome music going on. Buffalo Springfield were so fucking good. The whole scene had this amazing inertia. Everyone was playing day and night, working their asses off. It was probably the greatest music ever.”

Soon Moby Grape were the most talked-about phenomenon in town. While many of their peers tripped about the cosmos with acid jams and stoned mantras, the Grape hot-wired themselves to the raw soul of rock’n’roll. Urgent and aggressive, they cut through the fug like a flashing blade. “We played into this thing of being punks,” explains Lewis. “With the exception of Skip, we were all club musicians. And club musicians had this kind of subcultural attitude where you pushed everybody around with a sort of controlled foolishness.”

Big Brother’s Sam Andrew, an Ark regular, declared them better than the Beatles. Fascinated by the inimitable Spence, Steven Stills and Neil Young became fans too, Buffalo Springfield alternating sets with the Grape during their residency. When they weren’t there, Stills and Young would be off spreading the word.

Inevitably, the majors labels soon came calling. Columbia Records producer David Rubinson turned up one night to see headliners the Sparrow (soon to be known as Steppenwolf). As it turned out, they were blown away by the opening act, Moby Grape. A host of others – Elektra’s Paul Rothchild included – were clambering for their signature, too. But when it came to business, things were already turning sour.

“I thought Matthew Katz was cool at first,” admits Stevenson. “He had credentials and did a hell of a job in doing the promotion and getting the Ark going. I guess he called himself the Pied Piper of San Francisco or something. We were all pretty optimistic, but it was probably very naïve of us.”

In October ’66, having already signed management and publishing agreements with Katz, the band unwittingly signed away ownership of their name, too. “We were just stupid young guys,” Mosley admits. “Rubinson had come out from New York to try and sign us to CBS. So Katz told him that if we didn’t sign contracts giving up the name and management and rights to publishing, he’d stop the contract from happening.”

Lewis: “We were so young. All we wanted to do was be free. What made us feel worse was that Buffalo Springfield seemed to be getting along fine. They didn’t like Katz at all. Neil Young was up there at the Ark, sitting right there when we were told we had to sign this paper giving away rights to the name. I remember him sitting there, playing this orange Gretsch he had and staring down at his feet. He didn’t say anything. But after that meeting, he told us not to do it. Don’t ask me why, but we did. When Rubinson came along, he said that if we signed with Columbia he’d get rid of Katz for us. Then after he got us signed [in February 1967] he came back and said that the Columbia lawyers couldn’t do it, that they’d made a deal behind our backs. Then we were really screwed.”

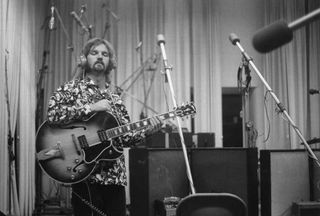

Nevertheless, in early ’67 Moby Grape headed for Hollywood to record their debut LP.

Helmed by Rubinson and made in just 13 days for a paltry $11,000, the results were spectacular. “When you’re broke and prepared, it’s amazing what you can achieve,” Stevenson laughs. “We just didn’t know any better. We’d rehearsed well and knew all our parts.”

“The band had a lot of chops,” Lewis explains. “When I first heard Jerry, it was like ‘Fuck!’

Skip loved Buffalo Springfield, used to talk about them all the time; this whole idea of having three guitarists. The chemistry was so good. We realised that if we could present that to people, we’d produce something that they’d like.” In the studio, Spence was both catalyst and talisman.

“He was a jubilant guy, a real outgoing hippy,” says Mosley. “He really made the music happen. He’d do a lot of arranging during rehearsals. The strangest thing was, his singing voice didn’t shine until we got into the studio. That’s when it really came through.” Crackling alongside Miller/Stevenson rockets Hey Grandma and Changes were Lewis’s roaring Fall On You and patchouli-scented ballad Sitting By The Window.

Radically realigned by Spence, Miller’s Someday disappeared into the kind of strange harmonic mists usually reserved for the Byrds. Mosley’s soul-searing Come In The Morning and Lazy Me marked him down as a white Wilson Pickett on a Motown tip. Then there was Spence’s rippling Indifference – complete with echoing be in the hub of it.”

Lewis says: “There was a magic up there, an innocence about the place, whereas Los Angeles, where I grew up, was always desolation row.” With Katz as self-appointed mentor, the Grape got together in his Polk Street basement. The rapport was instant. With Stevenson and bassist Mosley locking down the rhythm, it was pretty unique, too.

“Everybody wrote, everybody sang and everybody played,” Miller enthuses. “What was great was that Skippy played really good basic rhythm, Peter played complementary finger-picking style, and I was left to do my thing. Even though there were three guitars, each one of us had a wide open space to play in.”

After an inauspicious start – Moby Grape’s first gig was at California Hall in front of a reported five people – the quintet started playing at an old houseboat-turned-club in Sausalito, the Ark. The schedule was relentless, often stretching until dawn.

Stevenson: “We’d play there after hours. guitar riffs and wholly unexpected key change – and perhaps the greatest song in the Grape canon: the devastating Omaha (later covered by, among others, Michael Stipe with the Golden Palominos).

As classic debuts go, Moby Grape is up there with Television’s Marquee Moon or The Velvet Underground And Nico. Live on stage, too, the band were exhilarating. “I’d put my vocal mic in front of one of my old basses and get a beautiful natural echo,” smiles Miller. “Then we’d start doing things like Dark Magic and Space Now and get everybody off to what we called the Purple Planet. The eyeballs would be bugging out.”

The Grape didn’t know it then, but they had already peaked. Next came Columbia’s laudable hard sell. For a band that didn’t need it, Moby Grape were hyped to hell. On June 6, 1967, at the Avalon Ballroom, CBS threw an outrageously lavish press junket to launch the album. Journalists were flown in from all over the States to witness the Next Big Thing.

Mosley: “I remember parking the Porsche, walking in and there were two people at the door who handed you a five-singles box set and a bottle of wine with ‘Moby Grape’ on the label. There were millions of purple orchids flying from the ceiling; they were all over the floor.”

In addition to turning the floor into an orchid icerink, Columbia’s smart marketing men also neglected to provide corkscrews for the 700 bottles of wine.

And then there was the singles fiasco. Convinced of their marketability, CBS took the unprecedented step of simultaneously releasing five Grape 45s. Inside the purple velvet press pack, they claimed that “the label is convinced that each of the 10 sides has the potential to make it to the top of the national charts”. There was also a Moby Grape Manual issued to sales and promotion execs. Confused by the ploy, radio stations didn’t know which single to play. “That whole thing was nuts,” says Miller. “If they’d just put out Omaha with 8:05 on the B-side, people would have known what to push. That would have been the big hit.”

Out in radio land, the backlash began. “In retrospect,” Stevenson offers, “you can see that people thought we were hyped. And we weren’t. That’s a completely unfair assessment of us then and now.” To compound matters, the Avalon night had ended with the arrest of Miller, Lewis and Spence up in the Marin County hills. Caught with three underage girls, they were charged with contributing to the delinquency of minors and – in Miller’s case – possession of marijuana.

“It was bullshit,” contends Miller. “The way it came out was that it was just the Grape involved, but it wasn’t. There was a whole bunch of people out there on the mountain looking at the stars. Then everybody scrambled when the police came. I had one of the roadie’s Mustangs at the time. The police ploughed through the ashtray until they found what they thought was an empty marijuana paper. But there was nothing there. And the stuff about the girls was bullshit too. So we spent the night in a holding facility and the papers are full of ‘Moby Grape busted on drug charges!’ They really made it look ugly.” All charges were dropped, but the mud stuck.

“Actually,” Lewis asserts, “it was good publicity. The Doors would have just jumped on that. But instead, Columbia got freaked out.”

The band were packed off on a US tour with the Buckinghams and the Mamas And The Papas. “That’s really when we started going south,” concedes Stevenson.

Mindful of the Marin County incident, some promoters panicked and cancelled dates. To compound things, the Grape (having been promised equal billing) would find themselves in tiny letters underneath the Buckinghams, with the Mamas And The Papas headlining.

“At one point, we were beside ourselves,” says Lewis, “so Skippy ran out on stage while the kids were all screaming at the Buckinghams and screwed the whole thing up. When we came on and played, we were crazy and animated. People were saying: ‘What the fuck is that?’” The Grape’s frenzied set would blow everyone out of the water. The Mamas And The Papas’ mellow vibe seemed like extended anti-climax.

“It wasn’t the best way to bring them on,” says Stevenson. “We’d end with Omaha and it sounded like a buzzsaw going off. Then they’d come on and do something super-soft like Monday Monday.”

Lewis: “By the time they came on, people were filing out. The next day at breakfast, Mama Cass came up to us and said: ‘You guys are a bunch of punks. You should be grateful to tour with the biggest band in America.’ We survived one more date, then The Mamas And The Papas kicked us off the tour.”

With Columbia eager to recoup expenses, Moby Grape were hurried into the studio to record their follow-up album, Wow, with Rubinson again producing.

It was too early. Exasperated by their hard partying, the label decided to send them to New York, where there were supposedly fewer distractions. It turned out to be a disastrous call. The band were kicked out of Manhattan hotels for ill behaviour.

“Going to New York just brought trouble to New York,” says Mosley.

Recordings were disjointed. Only two or three members would be present at any one time. As a counter, Rubinson smothered the songs with horns and strings.

Lewis returned to LA to try and save his failing marriage, but failed. “When I went back to the band,” he remembers, “I started medicating myself with downers so I wouldn’t be too upset about it all. The rest of my time with the band was kinda like a Fellini movie. I remember some of it, but most of it was like wandering around in a haze of pot smoke and barbiturates.”

Then Skip got into serious trouble, taking up with a white witch called Joanna Stevenson: “He was living down in the Village and taking quite a lot of hallucinogenics. There was an old man hanging out with Skip and Joanna, too, who they’d picked up off the street. It was strange. The old guy was some sort of oracle and Joanna was a self-proclaimed witch. She definitely had powers over Skip.”

Lewis: “Skip was a very Messianic character. People would get with him and he’d convert them into these admirers, or sycophants, and get them on Skippy’s trip. But with this girl it was the other way round. She worked him.

“In the 60s, there were these chicks who were like sex witches. They used their crank as a whip. There were all these girls who’d been repressed, taken LSD, then all of a sudden it was like the leash was off. And they realised they could use this thing. Skippy was the ladies’ man. He loved women to the point where he’d want to hang out with them more than the guys. So he was the perfect candidate for that – meeting somebody who gives him lots of drugs. Then all of a sudden Skippy shows up with a fire axe and he’s gonna change the whole thing.”

Stevenson: “It was kinda like the spirit of Charles Manson. It was around the same time, and there was some strange stuff going on. Cosmic stuff which is hard to explain. And some of these spiritual forces really bought into murder and mayhem. I really didn’t think it was down to Skippy. “We were staying at the Albert Hotel when Skippy came looking for us. Luckily Jerry and I were at the studio. I guess he took a fire axe and took it to the door. It was like, ‘Here’s Johnny!’ When he went to the hotel, we were at the studio, and when we came looking for us at the studio we were back at the hotel. Murder and mayhem never had their way, though the potential was there.”

When Spence eventually arrived at the studio, he was disarmed by Rubinson.

Mosley also had a close call. “He freaked out on us,”he recounts. “I went into the office of Bob Cato, CBS’s art director at the time, and Skip and Joanna were there. Skip was going to leave Moby Grape and go off on his own, and he asked me if I wanted to join him.

I said: ‘Yeah, but I don’t want your girlfriend around, telling me what to do.’ She jumped up and started firing at me, so I grabbed her hands, threw her against the wall and took off. Then she got a pair of scissors and went after Cato with them. So he called the cops. The cops picked them both up and Skip and Joanna went to jail. I wouldn’t press charges, but Cato did. Next thing I know I’m in a courthouse with [then Grape manager] Michael Gruber and they’re sending Skip and Joanna off to Bellevue [a New York mental hospital]. The Grape were totally shocked. We hauled ass straight back to San Francisco.”

Released in June 1968, Wow was hardly a disaster (it peaked at No.20 in the US), but it was a disjointed affair. Mosley’s creepily hypnotic Rose Coloured Eyes and Bitter Wind – despite being drenched in backwards effects – were classic Grape, as was Stevenson’s funked-up Murder In My Heart For The Judge and Spence’s clap of dirty thunder, Motorcycle Irene.

With Spence gone, the foursome regrouped in Santa Cruz and began working on what became Moby Grape ’69. Although all concerned admitted it was a rushed affair, today it sounds like the perfect comedown album. Rootsy and introspective, it reads like the distillation of years of broken promises and false dawns.

Rubinson’s laughably apologetic sleevenotes attest to the guilt implicit in CBS’s handling of the band: ‘Few recording acts get the initial build-up which the Grape got when they started. They themselves demanded the enormous hype… but they didn’t know what they had started (nor did I) and, logically, they couldn’t ever live up to their notices.’

“Rubinson’s whole trip was in going up to Bob and telling him it was all about him,” says Lewis. He caused a lot of dissension. With Moby Grape, when you get all these energies together, you come up with these great songs. But soon as you start manipulating these guys and turning one against the other, it’s over. That’s how I explain our demise.

“Around Moby Grape ’69 we were all going through a period of introspection, trying to make sense of everything. The other records we’d made had been to get an effect from everyone, so they’d think we were great. Moby Grape ’69 reminded me of The Notorious Byrd Brothers. You can achieve greatness with those kinds of songs, but it depends if you’re willing to make that step. Sometimes, all you want to do is go to bed and start sucking your thumb.”

After a tour of Europe (during which the Beatles declared themselves Grape fans), Mosley had had enough. He quit for the Marines. Miller: “That was really strange. He was 26 years old. I would have thought Woodstock would have been more fun. I guess it was a stability thing with Bob. He wanted to be as far away from any hippies as he could.”

Mosley: “After Moby Grape ’69 it just started getting boring for me.

I didn’t have nothin’ to do. I wasn’t sick of rock’n’roll, it was the fact I wasn’t doing anything. I was just trying to move on. So I went back to college, then I got a draft note from the army.” Developing schizophrenia, Mosley was discharged on a medical in July 1970.

“They’ve been paying me ever since,” he says. “I take some medication once in while and I’m in pretty good shape.”

For the Grape, their career was nearly all over. Recorded over three days in May 1969, Truly Fine Citizen (with just Miller, Stevenson and a reluctant Lewis) was little more than contract filler. Meanwhile, ex-manager Matthew Katz – given the boot by the Grape in September ’67 – had launched a lawsuit against the band, claiming he still had ownership of the name. In 1970 the California Labour Commissioner voided all Katz’s contracts with Moby Grape, but his appeal meant the issue lay dormant for another three years. Meanwhile, Katz formed a fake version of the band and sent them on the road.

An appalling cock-up at the August 1973 trial – in which a Moby Grape attorney fraudulently executed a settlement of the claims, effectively handing ownership of name and songs back to Katz – meant the bogus group could carry on indefinitely.

Miller: “People knew they weren’t the real Grape. It never worked for Matthew. He thought he was Moby Grape. If Matthew found out about us trying to do something,he’d put an injunction in. And it’d end up being a nightmare for the promoter. He’d have to run to the court. We didn’t want to keep putting people through that, so we’d play around with names, like the Melvilles.”

Mosley: “Katz was just an asshole to begin with. We also did a movie for 20th Century Fox called Sweet Ride. He got his fingers into that, so we didn’t get paid either. It’s been going that way for a long time. He’s got his own record label and he’s been putting out his own Moby Grape stuff that’s been leased to him by CBS. He’s made a lot of money off that and all the fake versions of the Grape he’s been putting together over the years. We never made any money from Moby Grape.”

No band has fought harder to preserve their identity and purify their legacy than the Grape. There have been various reunions down the years, although they cite 1990’s Legendary Grape – all four members, with Spence in spirit only – as their true follow-up to 1967’s debut. Spence, whose troubled life ended when he died of lung cancer in 1999, aged 52, never saw justice done. Which fiercely strengthens the resolve of Lewis, Miller, Stevenson and Mosley today.

“We’ve definitely bonded over the Katz litigation,” Stevenson says. “If you have something you’re all united against, it can unite you together. The Katz thing is what’s always put this band and its purpose at the forefront of our minds and lives at any given moment. When you look at what guys like [current Grape lawyer] Glen Miskel have done to try and get us our publishing rights and royalties back, it’s an amazing thing. It’s an important issue in all our lives.

And ironic that Matthew, of all people, is the one who’s ultimately been responsible for us to unite at any given moment.”

Some time in 2000, Lewis came face to face with Katz in court: “Katz was there, hugging me and saying that we shouldn’t have lawyers to decide everything.

I told him: ‘I don’t want to hug you, Matthew. But I’ll say this: I buried your protégé last year. I felt his hand go cold in mine. This guy died like a mouse without his cheese while you were spending his publishing money on whatever you spend your shitty money on. I want to say this on his behalf: if this whole thing was about your redemption, so that you could see that what you did to us wasn’t a cool thing, then I think he would have told you it was worthwhile. Because that’s the kind of guy Skippy was. But Matthew, go and sin no more.’ So he leaves the court, weeping. Then the next day he calls the court and tries to vacate the settlement because he didn’t think he got what he wanted!”

A breakthrough came, however, in a San Francisco court in March 2005. All four survivors and the estate of Spence filed a suit against Katz to finally resolve the litigation that has stretched across four decades. The five-day trial found favour with the Grape.

In its final statement of decision on July 20, the Superior Court Of California decreed that all ownership rights relating to recordings and songs prior to 1973 are the sole property of Moby Grape. It also stipulated that Katz was to pay back royalties. And that the band members now owned the Moby Grape name.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the history, Katz appealed. But on July 7, 2006, the Court Of Appeal upheld the original verdict. It was a momentous day for all concerned.

So, having achieved some kind of closure, what now? In the past, Mosley has been the least certain of a Grape reunion, citing geographical limitations as the main hurdle (Miller lives in Tacoma; Lewis in Santa Barbara; Stevenson in British Columbia, Canada; Mosley in San Francisco). But the wind now seems to be in Moby Grape’s sail. Lately, with Omar Spence filling in for his father, the band have been busy rehearsing for a new album.

Miller is thrilled about the reunion plans: “Bob, Don, Pete and myself are still healthy, so we’re thinking of going down to Santa Cruz and maybe doing a tribute to Skippy. Once you’ve got the idea and the energy, there’s no reason why it shouldn’t work. That whole thing we had together was so powerful.”

Who knows? The Purple Planet may still be out there.