The turning point may well have been the moment that Tony Blackburn heard Pinball Wizard for the first time and pronounced it “sick”. The Who had always been controversial; they had consistently been louder and harder than any of their contemporaries in the British charts; they had written the book on the art of hell-raising; and they had destroyed many more guitars, drum kits and speaker cabinets than they could possibly pay for. But now, lyrically, they were venturing into new and adult territory.

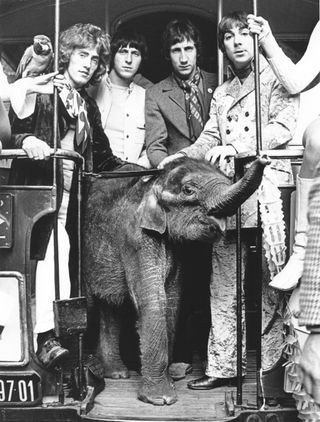

And with that came a wider approach to the music The Who were making. The one-time mods from Shepherds Bush had thrown away their natty ties and Union Jackets, plus the fussy shirts and floral prints they had briefly adopted during psychedelia. Now they were emerging as the era’s consummate rock band. And if they looked the part, they sounded like it, too.

For better or for worse, The Who were about to introduce the world to the ‘rock opera’.

From 1969 through to 1978, The Who would give Led Zeppelin a run for their money as the greatest rock band anywhere, careering from one triumphant peak to another and leaving in their wake a trail of chaos, devastation, burning rubble, smoking stages and smashed-up hotel rooms.

The Kinks had invented the heavy metal riff in 1964 with their You Really Got Me. But The Who, with their first run of hits the following year, were clearly a tougher proposition. The short, sharp, truculent outbursts of I Can’t Explain, Anyway Anyhow Anywhere and My Generation – the timeless battle-cry of the angry young man or woman – expressed a belligerence hitherto unknown in British pop.

They may have dressed smartly and spectacularly in Carnaby Street’s finest threads, but The Who were not about to revel in the euphoria of Swinging London. They were not mindless, they were not complacent, they were not content – and they were therefore very special.

In Pete Townshend they had an enormously intelligent thinker, a musical genius and an outrageously explosive performer. Townshend never loved Roger Daltrey, and their personal animosities would produce the final spark of frustration that made The Who such a combustible and tumultuous live band. Daltrey was, of course, the ideal frontman for all of this boiling aggression. On stage, he would react to Townshend’s rage with a furious energy of his own. On TV, even in the earliest days, Daltrey’s sullen glare was in startling contrast to the delivery of so many other grinning, goofy popsters of the era.

Stirring up a whole bunch of mischief of his own, both on and off stage, was the baby-faced Keith Moon. He was described in his Alperton Secondary School reports as ‘rather young for his age’, ‘idiotic’ and ‘retarded artistically’. His behaviour in The Who was equally child-like and attention-seeking, although hilarious at the same time. His extravagant, gurning, forward-drumming, cymbal-crashing bravado can be seen, retrospectively, to be right in character.

With three such battling egos continually colliding and erupting in one band, John Entwistle’s role as ‘The Ox’, the straight man, the strong, solid and utterly immovable bass player, was the crucial grounding force, the springboard from which all kinds of mayhem could spontaneously blow up.

In 1965, ‘rock stars’ as we know them now did not exist. But if anybody had the line-up, the chemistry, the attitude and the talent to be rock gods of the future, it was The Who. We knew it even then, but we couldn’t explain.

My Generation had been a classic, defining statement. But Substitute, which charted in March 1966, was the great consolidation. It was the moment of clarity, the one in which The Who achieved the perfect mix of musical violence, melodic verve and savage social comment. No other record that year was so primitive and so powerful, except perhaps for the Small Faces’ All Or Nothing, which followed in the late summer.

Coincidentally, both groups would soon wander way off the mark they had each made so memorably with those two songs, being sure to wear a few flowers in their hair, or at least drop a tab or two of acid, when it was the cool thing to do for a while. Steve Marriott’s band carried on from there, successfully, into vaudevillian Cockney whimsy; The Who eventually plugged back into the socket that had electrified both themselves and the public. It took a couple of years, though.

Not that there had been anything too dreadful about The Who’s A Legal Matter or (especially) The Kids Are Alright; I’m A Boy and Pictures Of Lily were amusingly naughty, although the lightweight Happy Jack had been only mildly diverting.

Treading water with a year-old song, I Can See For Miles, in October 1967 and Magic Bus a year later, The Who needed to reconnect with the forcefulness that had propelled them to their early successes. But they still had some way to go to rival the stark intensity of My Generation or the tuneful brutality of Substitute.

They had just about survived a series of bitter arguments and physical fights. They were also aware that whatever they did next had to be really brilliant, because they were in a shit-or-bust situation: they had trashed so much equipment at gigs that they could no longer survive financially, even though they had hired-hands continually picking up bits of guitar for Townshend to glue back together and trying to salvage whatever was possible from the debris of each night’s show.

It was the biggest gamble of their career. Townshend had been writing a rock opera called Tommy, which The Who would release as their next album. If it failed they would have to split the group. If it succeeded – which, of course, it did beyond their wildest dreams – then they would be able to stay in business.

Townshend had been toying with the idea of a rock opera for some time. Early on, he had considered writing one specifically for singer Arthur Brown. He intended to call it Rael.

The Who album A Quick One, released at the end of 1966, contained what was billed as a ‘mini-opera’ – A Quick One While He’s Away – which ran to 10 minutes (an unprecedented audacity in those days) and was crafted from a number of Townshend pieces slotted together.

With The Who Sell Out, released in January 1968, the band produced a pop-art concept album focusing on marketing and advertising. Their original plan to include real adverts on the LP did not materialise, but The Who, it seems, were ahead of their time – some 18 years later that idea would be turned into a reality by preposterous rock renegades Sigue Sigue Sputnik on their Flaunt It album.

So The Who had done a little bit of opera, they’d done a lot of ‘concept’, and it only remained for Townshend to fuse the two together. That he and the band would succeed with such confidence, style and imagination – and such a huge understanding of theatrics and dynamics – came as a surprise to everyone.

Tommy was The Who’s entry into the world of rock heroism. They had always been a singles group, and they would continue to put out excellent singles, but from now on they would function primarily as an albums band. This made a world of difference, both in how they would proceed with their music and in how they would be assessed, respected and adored.

The double Tommy was also a pioneering release. It wasn’t the first-ever rock opera (the Pretty Things had beaten them to it with S.F. Sorrow in 1968) but it was the one that swept an ambitious format into the mainstream, setting an astonishing precedent as it streaked up to No.2 in the UK albums chart in the early summer of 1969, and then to No.4 in the US.

Townshend had written some of the songs earlier, earmarking them only generally for a possible later use and not necessarily to be part of his masterwork. However, Welcome, We’re Not Gonna Take It, Underture and Sensation happened to suit the general atmosphere of Tommy as it came together, and were easily incorporated.

Other tracks were, of course, written specifically to tell the story of the deaf, dumb and blind kid – Tommy – who can only interpret the activities of the people and the things around him through vibrations – or music. As a result of Tommy’s extreme sensitivity, he is able to achieve heroic status and invoke religious fervour as the undisputed champion of the pinball machine.

Tommy, a normal child traumatised (by witnessing a murder) into his state of extreme disability, has also been subjected to LSD (The Acid Queen) and abused by his wicked Uncle Ernie (Fiddle About) – which would seemingly support Townshend’s recent contention that he has for many years been concerned about the effects of child abuse, having himself been a victim. But that’s a whole other subject.

The story of Tommy is allegorical. On one level it aimed to reflect the rise, the glory and the subsequent fall of a pop star. On another it represents the spiritual quest of a young man who was reputedly Townshend himself. The Who guitarist had been in and out of the psychedelic experience, enduring a terrifying STP trip during the flight that brought him back to England after the Monterey Pop festival in 1967. Asserting that mind-altering drugs could rip a personality apart without any guarantee of putting it back together, Townshend had taken refuge and comfort in the teachings of Eastern guru Meher Baba, and the guitarist was determined to chart this personal journey in his writing.

But if Tommy was a massive confessional for Townshend, it meant just as much to Roger Daltrey, who later revealed that it enabled him, finally, to find a real voice in The Who. And what he found was a rock voice. A rock voice that still ranks among the finest ever committed to vinyl.

The Who were working on Tommy throughout the second half of 1968, and their excitement, their true commitment to the music the group were making, resulted in an unusually harmonious working atmosphere.

It emerged as an album of contrasts, of light and shade, with enormous power chords ringing out in urgent contrast to moments of fragility and calm, all fitting together perfectly. At the time, it was big and it was clever.

Even if curiosities such as Fiddle About and Cousin Kevin may now sound less than sensational, they were perceived at the time to serve a practical function as part of the narrative drive, and those two songs have never detracted from the triumphalism of Pinball Wizard (the first single to be taken from the album), the climactic drama of the See Me, Feel Me/Listening To You sequence, the exhilaration of I’m Free or the rampant anger of We’re Not Gonna Take It, with Tommy’s disciples finally turning on their messiah.

Released three months before the album, Pinball Wizard was a top-four hit – despite its failure to ring Tony Blackburn’s bell.

The Who were back. They were bad, beautiful and as brash as they had ever been – but now more colourful. Once again, they were contenders. And when they took Tommy out on tour in Europe and America, they were just unstoppable, and rose quickly into the realms of rock royalty.

The Who had always put on a spectacular show, but now they had a whole new set that was deserving of all of that passion and fire and raging intensity.

Daltrey acquired a new and aggressive sexuality as a performer. He was and is a smallish man, but his on-stage presence was enormous. Whirling his microphone lead around in the air like a lasso, his hair in long tangles, his chest bare and his sleeves bedecked with two-feet-long white fringes, he became the archetypal rock frontman – a situation that was quite new to him, since he had previously only been ‘the singer’. And even then it had taken Tommy to provide him with ‘the voice’.

Daltrey later explained that this was all made possible by the role-play required to bring the characters to life in the rock opera.

Townshend, at the opposite end of the spectrum, had taken a liking to wearing boiler suits. These undoubtedly facilitated the massive leaps with which he hurled himself and his guitar around the stage, windmilling his right arm wildly and attacking his equipment in nightly bursts of violence.

The demonic Keith Moon, certainly enthused by the band’s new popularity – and financial recovery – became increasingly outrageous, dressing in ever more ridiculous costumes, throwing hilarious shapes and making faces as he threw and caught drumsticks with effortless expertise. Moon also joined in Townshend’s concluding orgies of destruction, kicking his kit to pieces across the stage.

Yet Moon, in his own, flamboyant way, was a fabulous drummer, powerful and indefatigable as his percussive displays took flight from, but still usually observed, the security of John Entwistle’s rock-steady bass lines.

And still Entwistle didn’t move.

Playing at Woodstock, you’d think, would have been a highlight of this period. There, on August 16, 1969, The Who gave what is still considered to be one of their greatest shows, capturing the spirit of a generation no less, in front of the mud-slimed masses at Yasgur’s Farm in Bethel, New York. But as Daltrey groaned later: “It was the worst performance we ever did.”

The Who had been required to hang around in the swampy chaos that was Woodstock for around 15 hours, finally taking the stage in the darkness of the early morning. And, like many artists appearing, they had unwittingly ingested a lot of acid, since all of the drinks backstage had been spiked.

None of the band reportedly enjoyed the set. Townshend, in his misery and anger, attacked camera director Michael Wadleigh and then smashed his guitar over the head of left-wing militant Abbie Hoffman, who had made the mistake of walking on to The Who’s stage to protest at the jailing of MC5 manager John Sinclair.

The only bright spot was a literal one. The sun came up just as The Who finished their set, so that Townshend, personally, left the stage marvelling at nature’s coincidental light show.

With Woodstock sealing The Who’s reputation as gods among men, they went on that month to play with Bob Dylan at the August 31 Isle of Wight festival – and for once the band, their critics and their audiences all agreed that here The Who’s was a magnificent performance.

No one had ever seen or heard anything like the sound system they assembled for the festival; it was so loud that fans were warned not to come within 15 feet of the speakers.

So how could The Who follow Tommy? Certainly not with that most perilous of adventures, the live album?

In June 1970 they released Live At Leeds, which had (supposedly) been recorded at the city’s university four months earlier on St. Valentine’s Day. Now acclaimed as one of the most lethal live collections ever committed to vinyl (or compact disc), it captures both the diversity and the raw attack of The Who at maximum overdrive at the turn of the decade.

The band had recorded something like 80 hours’ worth of music from their recent US shows with a view to compiling a live album, but they chose to ditch everything from those tapes in favour of their incendiary performance at Leeds.

And as if to show that they were still a force to be reckoned with, that they could do even better than the next guys, they carried on by releasing the landmark Who’s Next.

Townshend had been having a frustrating time with his bandmates, trying to realise his plans for what he called the Lifehouse project (reactivated much later). Intending it to be an exploration of spirituality and an experiment in interaction between The Who and their audience, but unable fully to inspire his colleagues, a brandy-sodden and occasionally suicidal Townshend – now in the grip of alcoholism – admitted defeat for the time being. So all four members of The Who instead poured their energies into Who’s Next.

Somehow they gelled intuitively, unforgettably, in spite of whatever personal demons were afflicting Townshend and Moon, who was also reeling out of control. Released in September 1971, it would be The Who’s first and only number one album. But it was a deserving chart-topper.

The jewel in the crown of Who’s Next is Won’t Get Fooled Again – by a long way the most vigorous and vibrant accomplishment of their career. (This is despite the fact that it incorporates the synthesiser, an instrument viewed by purists at the time with great suspicion.) Destined to become an all-time rock anthem, it is an astonishing outpouring that alternates a chopping ferocity and an infectious swagger, topped off with some hair-raising yelling from Daltrey.

Also outstanding on the album is Townshend’s synth-dominated Baba O’Riley, which pays tribute at the same time to Meher Baba and to Terry Riley, a musical pioneer who had fascinated Townshend for years. (Riley’s Rainbow In Curved Air is still often cited as an early example of electronic music genius.) And Behind Blue Eyes remains a highlight.

But, typically, The Who had no real appreciation of the masterpiece they had just created with Who’s Next. As far as they were concerned, tomorrow was another day, and they had things to do.

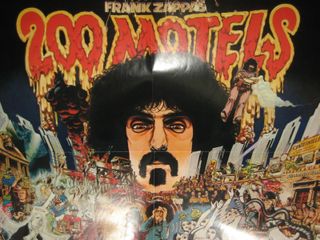

Together and individually, they were in great demand. In 1972, Entwistle released his second solo album and Townshend his first. Keith Moon turned up all over the place – in the early summer he joined his heroes the Beach Boys on stage at London’s Crystal Palace as a compere. He also made two memorable film appearances, playing a nun in Frank Zappa’s on-the-road movie 200 Motels, and a drummer in a holiday-camp band led by rocker Billy Fury in That’ll Be The Day, which co-starred Ringo Starr and singer David Essex.

The Who visited the charts only once that year. The creditable Join Together, a Top 10 hit in July, was one of a run of Who singles that had not been taken from albums, following The Seeker (1970) and the rather lacklustre Let’s See Action (1971). Relay, released in 1973, would be another such purpose-built single.

For the band, 1972 was really a quiet period, although they emerged at the end of the year to perform an orchestral version of Tommy at London’s Rainbow Theatre on December 9. That extravaganza, which involved some 200 singers, musicians and technicians, coincided with the release of Lou Reizner’s orchestral production of the album, featuring The Who, Ringo Starr, Rod Stewart, Maggie Bell, Stevie Winwood, Sandy Denny, Merry Clayton, Graham Bell, Richie Havens and Richard Harris.

Tommy was clearly not going to go away. But rather than react against the omnipresence of this most revered concept album, Townshend set about writing another one, Quadrophenia. Again it was a double album, and at its heart the theme is exactly the same as Tommy, dwelling on the search for spiritual enlightenment through the story of the central character, another young male. This time it’s Jimmy the mod.

Jimmy is unlucky enough to have four personalities. Each is attributed to a member of The Who, and each gives rise to a personal theme in Quadrophenia: Helpless Dancer (Daltrey), Love Reign O’er Me (Townshend), Bell Boy (Moon) and Doctor Jimmy (Is It Me?) (Entwistle).

Produced by The Who and released in the UK in November 1973 (a month later than in America), Quadrophenia had involved endless hours of complicated work in the studio, but it seemed a more accessible rock proposition than Tommy had been. Tracks such as 5.15 (issued as a single two months in advance of the album) were regarded as well up to the glorious standards of The Who.

Townshend hoped that Quadrophenia would replace Tommy in the public’s affection so that the band could drop completely, or at least reduce in number, the songs that audiences still expected to hear live from their epic opera from 1969. He had also fashioned the storyline to reflect the band’s early career as mods, in the expectation that they could then draw a line under it and move forward, free from these past, but persisting, associations.

Townshend could not wait to start playing a whole new live set – one which did not rely on Tommy and the band’s well-loved 60s singles.

To begin with, it was looking good. Quadrophenia was a No.2 smash hit on both sides of the Atlantic, and it received some tremendous reviews in the places that mattered.

But it turned out not to have the legs of Tommy. And, even worse, it was received unenthusiastically by concert audiences. Often it went down like the proverbial lead zeppelin, and Daltrey’s attempts to help by explaining the story on stage simply made matters worse. The public wanted Tommy and I Can’t Explain and My Generation and Substitute and Won’t Get Fooled Again; they didn’t want Quadrophenia.

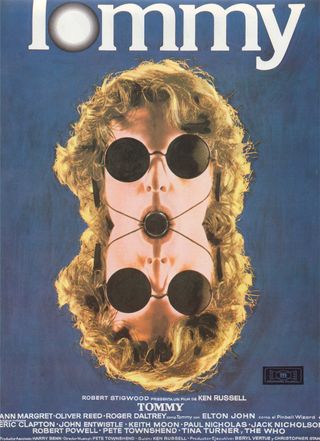

Townshend’s disillusionment with this state of affairs was compounded by Ken Russell’s film Tommy, which began shooting in spring 1974. It starred a mix of musicians – The Who, Elton John and Tina Turner – and actors, including Robert Powell, Ann-Margret, Oliver Reed and Jack Nicholson.

Of course, this latest production was a massive compliment to Townshend and to the band, and it was certainly a money-spinner, but it simply revived the cult of the deaf, dumb and blind kid playing his eternal mean pinball. In the mid-70s The Who reluctantly had to remove various songs from Quadrophenia live to make way for the crowd-pleasing Tommy selection, using innovative laser technology to sprinkle the audience with showers of starry, white light as Daltrey sang the first, quavering lines of See Me, Feel Me.

Time has been kinder to Quadrophenia. As with Tommy, the album was later made into a film, this time with the popular young actor Phil Daniels playing the title role, Jimmy, and it is generally considered to have stood the test of time more robustly than Russell’s Tommy movie. Likewise, these days the Quadrophenia record is usually rated more highly than Tommy.

The Who’s golden years were really over now, but they remained one of the world’s most devastating live rock bands.

The Who By Numbers, released in 1975, was received as a patchy business indeed, although it charted at No.7. It included the likeably tuneful Squeeze Box, which crashed into the Top 10 the following year as something of a novelty single, heaving with double and single entendres.

But it couldn’t hope to breathe the same air as such earlier standards as Won’t Get Fooled Again, and neither could Slip Kid, the follow-up, which disappeared without trace at the end of the long, hot summer of punk rock.

The times they were a-changin’, but The Who would go on to meet the new, young challenge more assuredly than many of their contemporaries did.

Their next album, Who Are You, released in August 1978 to a No.6 placing in the UK and a No.2 slot in America, was a solid enough collection, its title track recalling the apparent ease with which the band had achieved their previous, awe-inspiring balance of texture and testosterone. But the launch of the album was overshadowed by the shock death of drummer Keith Moon, which happened while he was asleep on the morning of September 7.

Earlier in the band’s career, Pete Townshend had given interviews about Who’s Next, stating his reluctance to hire a keyboard player for live gigs for fear of disturbing the crucial dynamics of the original four band members. And that view proved to be well-founded.

With the death of Moon, and his replacement in The Who by Kenney Jones, those crucial dynamics were injured irreparably.

The former Faces drummer enabled The Who to carry on, to do what they couldn’t have brought themselves to do before, to bring in keyboards for their concerts, and to turn out the occasional moment of inspiration in the recording studio, but the loss of Keith Moon left a wound that could never be healed.

Things could always be different, but they could never be the same. And they could never be as good again.

This was first published in Classic Rock issue 51.