In 1987, guitarist Dave ‘Snake’ Sabo, bassist Rachel Bolan and drummer Rob Affuso waited anxiously in the kitchen of the New Jersey house owned by the Sabo family. Guitarist Scotti Hill had been sent to the airport to meet an important arrival.

Also soaking up the atmosphere of expectation was Sabo’s mum, affectionately known to all as Mrs Snake. There was an acute awareness that the guy whose arrival they so nervously anticipated had to be the one. Frustrated by futile auditions and unsuitable appointments, the time had come for them to shit or get off the pot.

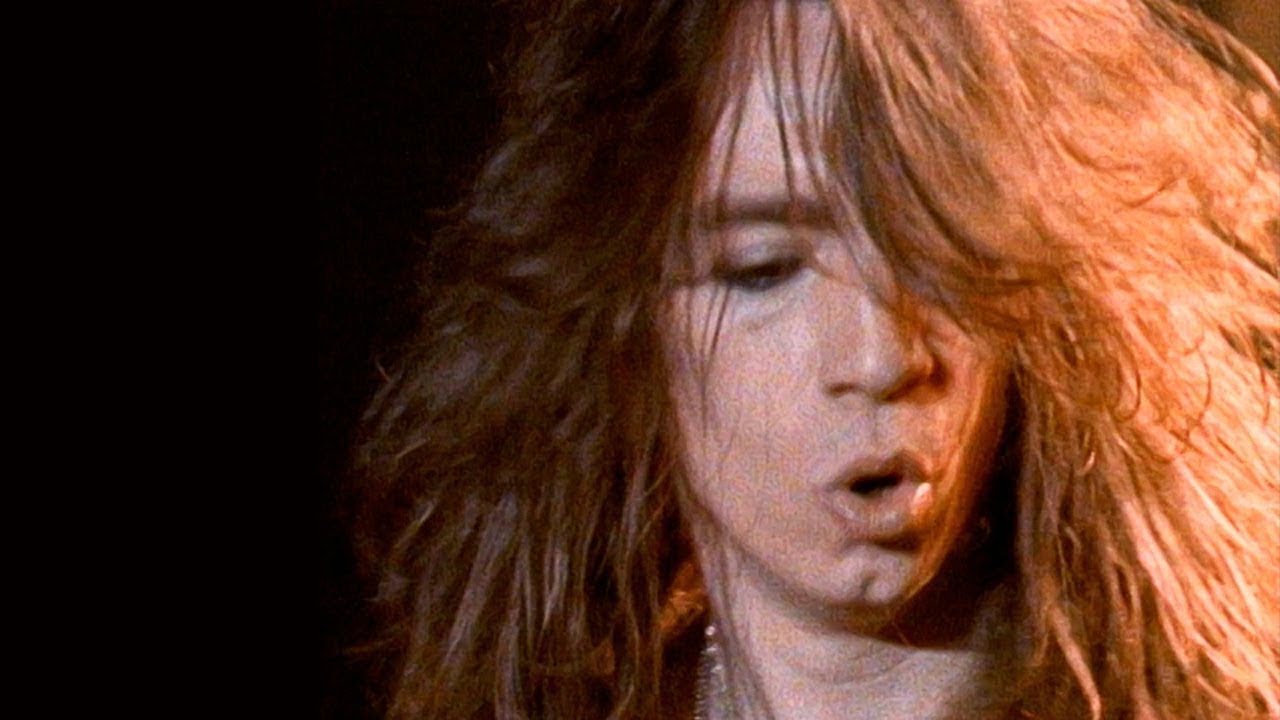

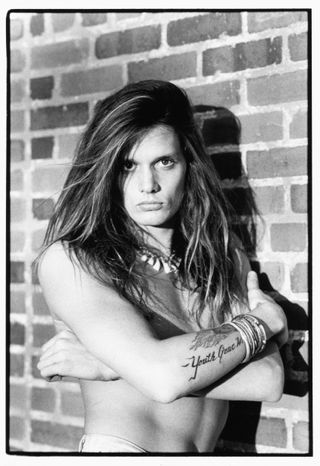

Finally, the door swung open, and the lead singer that Skid Row had pooled their cash to fly in from Canada ducked his head and entered the room. Six feet three of cheekbones, vanity and profanity, hair and attitude, Sebastian Bach broke the silence by gleefully introducing himself to all present: “Du-u-u-u-u-u-des! I’ve got a ten-inch dick!”

The blue touch paper had been well and truly lit, and for the next nine years Skid Row would achieve most of their rock’n’roll ambitions – although the triumph wasn’t to be without its share of agony. Sebastian Bach was the X-factor that transformed them into a world-class act. But the singer’s infantile hedonism was a constant source of irritation to the other reluctant occupants of his live-in bubble. Depending upon which day of the week it was, Skid Row would be adored, banned, sued, lauded for entering the Billboard album chart at No.1 or lambasted by their rivals. One thing, though, was for sure: they were rarely ignored.

Like all comets, Skid Row burned brightly for a relatively short time. And when their star eventually faded, its plummet back to Earth was seemingly unstoppable. Incredibly, however, the band exist again, and in 2003 gigged around the UK for the first time since a spot on the bill at 1995’s Castle Donington festival – but this time minus Bach, and much the happier for it.

The Skid Row story began in 1986, with a chance meeting between Dave Sabo and Rachel Bolan (real name James Southworth) in the New Jersey guitar shop where the former worked.

“I’ll never forget that moment,” Sabo recalls fondly. “This guy walked in wearing a red beret and a pink leather jacket. He looked like a freakin’ star. I just had to strike up a conversation.

“When it came to writing we very quickly realised that while we both came from different musical backgrounds – me from Judas Priest and Iron Maiden, while Rachel’s roots are in The Ramones – our styles complemented each other. It also helped that Kiss and Van Halen were a common denominator.”

Bolan proposed Scotti Hill (born Scotti Mulvehill) from a previous group he’d been in, and when their original choice as drummer was jailed for a stabbing, Sabo brought in Affuso from one of his own earlier bands. Bolan had played gigs since he was 16, sometimes having to be sneaked into bars in a flight case because he was underage, and there was never in any doubt in his mind that he would make the grade.

“Being an entertainer is something you’re born with, not something you can go to school for,” he maintains. “Whether you’re an artist, athlete or musician, it’s there inside you and you can’t shake it off.”

Sabo, too, had decided his own destiny at an early age. He and school pal Jon Bongiovi (who you may have heard of) had made a pact as seven-year-olds to become rock stars, swearing that whoever made it first would use their influence to help the other.

“It was obvious that Jon was gonna get there first, but he said that when our band was right he would go out on a limb for us,” Sabo relates. “And he was true to his word. Jon came to see us live, critiqued us and provided the benefit of his experience, which was invaluable.”

Right until the day Skid Row signed their first recording contract, the band rehearsed in the Bolan family’s garage in Toms River, NJ, using kerosene heaters to keep them warm in the winter – and with the TV in the house turned to full volume to drown out the racket. The patronage of Jon and his guitarist Richie Sambora was guaranteed to bring them a degree of expectation, and Doc McGhee (then Bon Jovi’s manager) signed them up.

Bolan says the group “pounded the New Jersey, New York and Connecticut scenes till people got sick of us”. But original singer Matt Fallon, who had also briefly been with Anthrax, lacked the rest of Skid Row’s drive. John Corabi, later of Mötley Crüe, was offered the job. Atlantic, Geffen and A&M had all expressed an interest in signing the band, but made it plain that the line-up had to be right.

A phone call came. Various industry people had seen a young singer jamming with Zakk Wylde, members of Twisted Sister and Kevin DuBrow of Quiet Riot at the wedding reception of photographer Mark Weiss. A mutual acquaintance put the newcomer, 19-year-old Sebastian Bach (born Sebastian Phillip Bierk, the Bahamas-born singer had cut his teeth with Kid Wikked, who recorded an album for Attic Records, then replaced Bret Kaiser in Madam X), in contact with Skid Row, and an audition quickly followed.

“He sang the songs so high that we had to reign him in, but after some work on his voice it all fell into place,” Bolan recalls. “Sebastian was very obnoxious and loud, but we needed a singer. The good thing was that he also had drive – and then some. But frontmen were supposed to have spirit, right?”

However, it didn’t take long for people to realise that as well as bringing along enormous positives, Bach also brought along pitfalls. There was an altercation in a bar on the very night of his arrival. Bolan now reveals that he had been warned of the singer’s volatility: “Somebody who’d been in the business for a while told me they foresaw lots of trouble down the road,” he relates. “But I wanted to make it, and none of us could stand the thought of seven more months looking for someone else.”

“That first night, we hung out at this local bar and ended up jamming on 18 And Life and a few other songs,” Sabo continues. “It was really, really awful. But Rachel announced from the stage that we had found our new singer. Later on Sebastian got really drunk and threw a punch at this guy, missing him by about a foot.”

The new-look band spent a year fine-tuning their act. A deal with JBJ and Sambora’s publishing company, Underground, was duly struck – an arrangement that they later regretted, as it allegedly diverted the lion’s share of the group’s royalties to the Bon Jovi pair. After a bidding war, Skid Row signed to Atlantic Records. However, it almost didn’t happen that way. The band had also played a “miserable” (Sabo’s word) showcase for Geffen, at which Tom Zutaut, the A&R man who signed Guns N’ Roses and Mötley Crüe, had displayed some alarming snobbery.

“One day Doc called and informed me we had signed to Geffen,” Sabo explains. “It was the day I’d been waiting for my whole life, but I was dismayed. This was the label that had told us we had maybe two or three songs good enough for an album. Tom had asked us where we rehearsed, and when I told him he said: ‘Well you won’t be seeing me in that garage’. I was amazed by his arrogance. It was like Geffen were doing Doc a favour.”

Having performed the songs countless times, recording the Skid Row album for Atlantic (who had later put in a better bid than Geffen’s) with Dokken/Alice Cooper producer Michael Wagener was a fairly painless experience. From the bombastic opening of Big Guns and the war-cry of Youth Gone Wild, to the more melodic 18 And Life and I Remember You, their debut was an album of maturity and quality. Just a year later, after accepting a six-month tour offer to open for Bon Jovi as they promoted the New Jersey album, it had sold a million copies in the US alone. And as well as playing at the biggest venues the Unites States had to offer (New Jersey’s Giant’s Stadium, for example, held 72,000 people), Skid Row showed their hunger by also playing their own club shows on nights off.

As singles, 18 And Life and I Remember You both made the US Top 10. Skid Row were soon moving in heavyweight circles, and appeared at the Moscow Music Peace Festival, a show organized by Doc McGhee as penance for being busted for drug smuggling. Others that played for McGhee’s Make A Difference Foundation, conceived to combat drug and alcohol abuse, included Bon Jovi, Ozzy Osbourne, Mötley Crüe and The Scorpions. Bolan’s most enduring memory was not playing the actual concert, but the pre-show press conference.

“A member from each band was picked, and I sat with Nikki [Sixx, of the Crüe], Klaus [Meine, Scorpions singer] and Ozzy,” he smiles. “The Scorpions were the only ones who’d played Russia before, and Klaus was asked what it felt like to be back. He gave this bonehead answer that The Scorpions had come to Moscow and were going to rock it like a hurricane. Ozzy said: ‘Oh, what a fucking wanker’, and Nikki and I almost died with laughter.”

In August 1989 Skids Row finally made their UK debut at Milton Keynes Bowl, opening a bill that included Vixen, Europe and headliners Bon Jovi. It was the start of a whirlwind love affair that saw them headline London’s Hammersmith Odeon just two months later.

“Looking out on all those faces at Milton Keynes was incredible,” Bolan says. “All my life I’d just wanted to go to England because my favourite bands – The Beatles, The Sex Pistols and The Rolling Stones – were from there. We’d become big in the States and we were confident enough to think we could repeat that anywhere. Scotti and I tried to go out into the crowd to watch Bon Jovi, but we got mobbed.”

During a show at London’s Marquee, Bach had famously invited the entire audience back to the Columbia Hotel for a drink. A sizeable crowd duly gathered in Lancaster Gate, only to be turned away at the door. Bach was incensed when he heard the fans were not being allowed in.

“I was gonna party with the people who’d taken the time to turn up,” he later said. “So when no one was looking I grabbed a bottle from the bar and few joints and went out the back exit. I sat in Hyde Park and chatted with 50 or 60 fans. That kind of thing goes to show who’s addicted to rock’n’roll and who’s addicted to their own ego.”

The group’s streetwise approach certainly helped word to spread like wildfire, and soon they had leapfrogged from the Marquee straight to the Odeon, where they were joined on stage by Lemmy for a version of Train Kept A-Rollin’ and Steve Harris and Nicko McBrain for Iron Maiden’s Wrathchild. Robert Plant was reportedly backstage and at an after-show party; The Sweet’s ex-singer Brian Connolly also arrived to express his admiration.

Bach had studied well for his role as a frontman, learning his trade at the Dee Snider School Of Abuse. At Hammersmith, possibly taking his cue from a bootleg of Twisted Sister that I’d given him, he used Snider’s ploy of abusing pop stars.

While Snider had launched verbal tirades against Boy George, Bach’s ire was aimed at pop stars of the era like Jason Donovan, Milli Vanilli and Bros. At the Odeon party, Bach had grabbed me in a headlock and admitted: “You must fucking hate me, man. I ripped off every last word from your tape.” Sure enough, his charisma sometimes enabled him to win over audiences almost single-handedly, yet his raps weren’t always equally well-received.

“It used to bug the hell out of me when he said things that Dee Snider, David Lee Roth and even Paul Stanley had used before,” Bolan says now. “It was so obvious. As our career progressed, pretty much all the shit that Sebastian said on stage became irritating. He’d tell an audience what a song was about, but it had nothing to do with the lyrics I’d written. Unless I ignored it, I’d have walked off.”

However, Bach’s personality and songs like Youth Gone Wild and 18 And Life were having an almost Pied Piper effect on fans on both sides of the Atlantic. A UK tour with Mötley Crüe saw Skid Row stepping up to bigger stages still. According to Bolan, Bach’s ego problems only really became an issue as the band’s initial flush of success began. Up until then, Sabo insists that each of the five members would have “taken a bullet” for a colleague. “It was absolutely true,” he now acknowledges. “Everything was so new, and the excitement of achieving our early goals was a real bonding experience. We were like a clenched fist.”

With sales snowballing, by 1989 Skid Row were firmly on target for huge stardom. “We’re still the same slobs we were before,” Bolan insisted at the time. sometimes our songs had something more than that, and it really helped us to connect with people.”

But Bach seemed hell-bent on self-destruction. When Skid Row supported Aerosmith in Springfield, he was struck by a glass bottle thrown from the audience. In front of MTV cameras, he proceeded to hurl it back, resulting in 14- year-old Elizabeth Myers needing 125 stitches.

In later years Bach told Classic Rock that he was filled with regret for the consequences of that knee-jerk reaction, although he mused: “My sensible side tells me I wouldn’t do the same thing again, but when you get a glass bottle in your face and you’re dripping with blood… I can’t promise I wouldn’t kick somebody’s ass. I’m a human being, not a target.”

Bach himself paid half of the six-figure damages that ensued from the incident, the remainder coming from the pockets of his band-mates. The ensuing fallout was a significant milestone in Skid Row’s worsening personal relationships.

“Splitting that little girl’s head open…” Bolan sighs, almost lost for words. “Well, it was awful, and it put a huge wedge right in the centre of the band. That and the ‘Aids Kills Faggots’ T-shirt that he wore. Some kid had given it to him up in Winnipeg, and he put it on when we were in Los Angeles. I distinctly remember telling him: ‘I wouldn’t wear that if I were you’. But he did it anyway. By that point the stupid shit he was doing was almost becoming sociopathic. He seemed to feel that he was above all rules and regulations.”

The remainder of 1990 and start of 1991 was spent recording the Slave To The Grind album, again with Michael Wagener producing. It flew straight to the top of the Billboard chart – the first hard rock album to ever do so. It helped that the record was released the week before Van Halen’s For Unlawful Carnal Knowledge. Bolan agrees that the heaviness of Slave… alienated some fans, but by then the notoriety of Skid Row – or, more specifically, Bach – had reached new heights. The volatile singer made headlines when he rang me to express his indignation at a cover story in which Jon Bon Jovi had claimed: “I punched the shit out of Sebastian, decked him on his fat little ass and I’d do so again. I knocked him out and I’d do it again.”

A fracas had ensued on the penultimate night of the band’s US tour with Bon Jovi, with Jon believing that Bach had dissed the headliners from the stage. With end-of-tour pranks going on, Bach had been covered in milk and eggs by Bon Jovi’s crew before the show, and on stage launched into a semi-comic rant inviting Jon up to “have a piece of me-e-e-e-e!” As he went down the ramp afterwards, Bon Jovi and an entourage of heavies were waiting for him.

“Jon took a swing and missed, so I punched him on the chin,” Bach seethed, almost apoplectic with rage as he vented his version of events down the phone line. “Suddenly I’m pinned against the wall by four bodyguards; even my own tour manager was holding me back. Look, I’m a 22-year-old fucking Metallica freak on speed. I’m psychotic. I can drink four bottles of whiskey before I go on stage. Jon is a 31-year-old Bruce Springsteen fan with a fax machine. He gets pissed on one drink. Who do you think is gonna win a fight?”

He then rubbed salt into the wound by sneering: “Rock’n’roll is about coming together as one with an audience, not worrying about how to turn a sixty-nine-million-dollar fortune into a seventy-one-million one.” For his sheer audacity, Bach claimed to have received congratulatory calls from Axl Rose and Metallica’s Lars Ulrich, but it put Sabo in an impossible position.

“Jon had freaked out because he thought Sebastian had called him a pussy,” Sabo says . “But the whole thing was a misunderstanding, and because my singer hadn’t done anything wrong I had to defend him amid all this mud-slinging.”

Sabo eventually made his peace with Jon almost three years later at the funeral of a mutual friend. “The guy who’d died hated the fact that Jon and I were estranged,” he says. “He and I ended up hugging at the wake, and he invited me to his house that night where he, [his wife] Dorothea and I shared few bottles of wine.”

One positive to result from Bach’s outburst was that Jon and Sambora relaxed Skid Row’s contract with Underground, with the proviso that Bach signed a gagging order. Bolan now reveals that although royalties were never backdated, the band did at least start to receive regular payments. “I wouldn’t have minded a couple of the cheques they made out of us,” Bolan says, surprisingly flippantly.

To Bolan’s frustration, drug use had also begun to creep into Skid Row, especially on Bach’s part, although for the record the singer insists he hasn’t taken cocaine since 1993. “We had everything in front of us,” Bolan sighs. “It became a sore point. To this day I tell people never to do drugs, they’ll end up destroying themselves or what they’re working towards.”

On the following tour saw Skid Row headlining all over the world, with Soundgarden and Pantera among the bands supporting them. At a show at London’s Docklands Arena, Bach stunned fans by dropping his silver strides to his ankles and ceremoniously wiping his arse on a copy of the Daily Star. Skid Row also supported Guns N’ Roses at Wembley Stadium, where they defied a warning from Brent Council not to play the song Get The Fuck Out. Risking jail and a lifetime ban from the London borough, Bach once again infuriated Bolan by reading out the council’s letter to 80,000 fans.

“That type of posed toughness was so dumb,” Bolan now admits, adding sarcastically: “How did a kid that went to prep school end up such a rebel?”

The appearance of the B-Sides Ourselves mini-album in 1993 served as testament to the record label’s hunger for Skid Row product . A collection of songs by Kiss, The Ramones, Judas Priest, Jimi Hendrix and Rush, it summed up the diversity of the band’s record collections and brought them another gold record.

However, two years away from the spotlight had done the group no favours, and by the time of the Subhuman Race album in March 1995 the Seattle revolution was still giving the industry a spring clean. Worse still, the group’s relationship with Bach was nearing breaking point, and they were being forced to address various issues publicly. During their lay-off, the band had even attempted mediation, with – of all people – the aforementioned Dee Snider doing his best to advise both sides.

Sabo had also been suffering from writer’s block: “When I came off tour I couldn’t write a fucking song to save my life.” Bach now maintains that he hears in the record more of Metallica/Bon Jovi/The Cult producer Bob Rock than the musicians. Bolan calls working with Rock a “horrible” experience, and was equally concerned that Bach was demanding a bigger role in the song writing.

“I could understand his desire to write songs,” Sabo reasons. “Rachel and I had been learning our craft for eleven years. Sebastian could sing 18 And Life way better than I ever could, but writing a song like that isn’t something you can just snap your fingers and learn. When that distinction got lost, that’s when the real troubles began. The most interesting thing about Sebastian’s ego was that it grew more and more out of control the smaller the band became.”

Reviews of the album were less than glowing: a “disappointed” Kerrang! admitted that several days were required for it to make sense; RAW magazine hedged its bets by saying: ‘Skid Row still have it in them to produce a classic rock album. This isn’t it.’

When in an interview I pointed out that the UK’s media had been underwhelmed by the third Skid Row album, Bach lost his rag, and stormed from the room, spitting back: “The press can write their goofy fuckin’ articles, and I’ll make my fuckin’ records. We’ll see who’s still doing it in ten years’ time. You’ve really hurt my feelings.” Sabo later summed up the group’s disillusionment: “We could’ve released Back In Black and it wouldn’t have mattered. It just wasn’t our time any more.”

Sure enough, Skid Row struggled through some US shows with Van Halen, but their death knell was sounded by agreeing to play some South American dates with Iron Maiden, Motörhead and Helloween. Not only were Skid Row stylistically out of place, but the bickering with Bach was also tearing them apart.

“I knew when I got off the plane at JFK Airport that I’d never step on stage with Skid Row again,” Bolan reflects sadly (and now, of course, we know he was wrong). “By then we were viewed as a cartoon band, and the genre we were lumped into had been swallowed up and laughed at.”

In Bach’s defence, Skid Row wrote songs about youth going wild and whom they claimed to represent, saying ‘fuck you’ to anyone who deserved it. So wasn’t it churlish to complain when somebody walked it like they talked it?

“If Sebastian had really meant it, then maybe so,” Bolan responds carefully. “But I know him and how he grew up. He hadn’t had to work. He was always kinda playing a role. We saw how he would cower and cry when we yelled at him. It was like standing up to a bully – they always eventually back down.”

Sabo, too, had reached the point of no return in South America, and finally sacked the singer by phone on December 23, 1996. There had been an offer to support Kiss, but Bach’s continued vetoing of the band’s material opened up what Sabo calls “an abyss of hatred”.

“I was eating a meal with my family when Sebastian left a vile answerphone message,” Sabo relates. “It was along the lines of: ‘You piece of shit, spineless cocksucker’. I’m gritting my teeth, my mother’s hearing all of this. When they’d all gone home I left a message on Sebastian’s phone telling him I’d received all his hate faxes and that I would never, ever play in a band with him again. When I called Doc to explain, he said he couldn’t believe it had taken me so long to do.”

The ensuing years saw Bolan form his own band called Prunella Scales (named after the comedienne who played Sybil Fawlty in Fawlty Towers). Bach joined The Last Hard Men, before touring under his own name. Sabo, Bolan, Hill and Affuso then brought in New Jersey singer Shawn McCabe for a project called Ozone Monday. In ’98 Affuso bailed out, although the group got as far as opening for Kiss and Mötley Crüe, and even recorded an album before McCabe quit the following summer.

“The 80s were hanging around our necks, but we almost didn’t want to say we’d been in Skid Row,” Bolan chuckles. “Although people assumed Ozone Monday was Skid Row with a different singer, we never did any of those songs and the whole thing really only served as a release.”

As a new millennium dawned, so did the realisation that they still had unfinished business. Affuso now has a career in marketing, so his place was taken by ex-Saigon Kick/Prunella Scales drummer Phil Varone. Nobody wanted to reopen the Pandora’s box that was Sebastian Bach, so they set about finding a new singer. After six people had auditioned unsuccessfully, the core trio of Sabo, Bolan and Hill began to get twitchy. Enter Dallas-born Johnny Solinger, discovered by Bolan via the internet. Thirty-five years old and with three studio albums with his own group Solinger under his belt, Solinger was invited to a jam.

Bolan: “His voice blew us away. And we knew right away we were gonna take him, but we didn’t actually tell him for three days. Six weeks later we were on the road with Kiss.”

“The band had balls of steel to take on a frontman like me,” Solinger maintains. “I don’t look or sing anything like Sebastian, and I don’t swing my head around half as much – do that these days and you’ll get laughed off a stage.”

A change of name was discussed, but ultimately the group were defiant. “We worked hard to build this band,” Bolan insists. “If people don’t believe there can be a Skid Row without Sebastian, that’s just their problem. We play old Skid Row songs and new ones, and just about everyone so far has accepted Johnny.”

The band’s determination to carry on led them to entitle their comeback album Thickskin. Aware of its importance, after they recorded it they scrapped it and then rebuilt it again almost from the ground up. Managing their own affairs and signed to their own label in America (although Thickskin has been released in Europe through SPV), their expectations are now considerably more modest than in the band’s multimillion-selling heyday.

The knowledge that that Skid Row are highly unlikely to sell five million copies of any new record is compensated by the new levels of camaraderie. In 2003 they even travel with a mobile bar.

“Yeah, it’s called Benders,” Bolan says. “The guys from Pantera gave it to us when they opened for us – it’s a gigantic, spotlit bar on wheels, part refrigerator and part stereo. It contains forty bottles of liquor. We took it out with us when we toured with Poison, and the thing needed restocking every two nights.”

Since 1996 there have been several lucrative offers to reunite with Bach, who himself told Classic Rock last year that he didn’t rule out singing with Skid Row in the future, but that if it happened “it’d all depend on the music”.

“Sebastian is delusional as always,” Bolan sighs. “He’s out of Skid Row and he’ll never rejoin. You might as well say Paul Di’Anno would go back to Iron Maiden. As much as he claims to hate singing our songs, his live record [1998’s Bring ’Em Bach Alive] is full of songs that he had very little to do with the writing of.”

Now fronting his latest band Bach Tight 5, Bach has spent much of recent years appearing in musicals, first a production of Jekyll & Hyde and then, even more fittingly, Jesus Christ Superstar. Bolan is keen to play down any suggestion of competition, despite Sebastian telling Classic Rock last year that he suspected Thickskin would never be released, while he had given the world “two fucking albums, three fucking musicals, and five tours”.

“It’s amusing that he has to recite his résumé to justify himself,” Bolan laughs hysterically. “When I buy a car I don’t say: ‘Hi, I’m the guy that played bass on the first heavy metal record to top the Billboard chart’. I don’t always need to be Rachel from Skid Row, sometimes it’s just nice to be Rachel the guy at the bar.”

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #62.