It’s 1967. Paul Rodgers is singing with a blues cover band called Brown Sugar, but he’s bored and looking for an escape. In moment of a perfect timing a young guitarist called Paul Kossoff shows up for a jam at one of Brown Sugar’s gigs, and Rodgers’ future (and that of rock music) is changed irrevocably.

Kossoff is the new hot-shot teenage lead guitarist, playing with Black Cat Bones – a blues band making something of a name for itself in the London scene. Despite this success, Kossoff is bored with playing 12-bar blues. And it just so happens that BCB’s drummer, Simon Kirke, is feeling the same way.

Andy Fraser, meanwhile, has just been ousted from John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers where he had been playing bass.

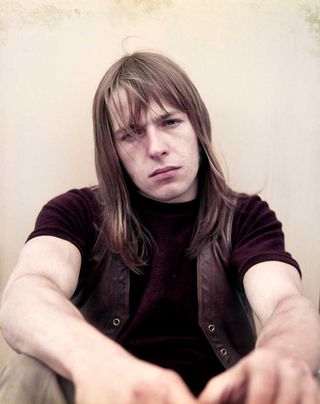

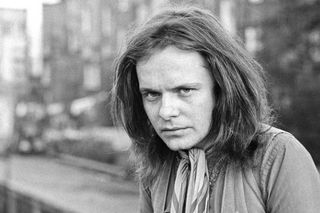

Simon Kirke: Black Cat Bones was a pretty average band playing blues standards but the guitarist stood out. He was a little bloke standing on the far right of the stage with a mane of long hair, and he was playing incredibly well. He wasn’t fast like Alvin Lee, more in the mould of [Eric] Clapton and [Fleetwood Mac’s Peter] Green. But I could tell he was the star of the show. He was, of course, Paul Kossoff.

During the break he came to the bar and ordered a drink. I sidled up to him and said that I thought he was a terrific player. He was self-assured and took the compliment well but not in a particularly big-headed way. In a rare moment of pushiness, I said that I didn’t think much of their drummer and offered my services. He said that actually this was the drummer’s last night and they were auditioning new ones the next day. They were leaving the gear set up and prospective drummers were being asked to play on Frank Perry [the outgoing man]’s kit, and if I wanted I should come along.

So the next afternoon, with just a pair of sticks and a heart full of hope, I did just that. We played a shuffle and a slow blues and I sat around while the other two hopefuls did the same. I remember the band going into a huddle and the leader, Stuart Brookes, coming up to me and saying I had the job. I floated home.

Paul Rodgers: I was looking for like-minded people and it’s funny because when you put that out there, it seems to draw those kinds of people. Paul Kossoff turned up for a jam at one of the Brown Sugar gigs and there was this instant spark because even the audience felt it. You could hear a pin drop when we played something like Stormy Monday Blues during the quiet passage. And he was as intense and emotional as I was about the music, about doing it. We were very passionate.

As soon as we got off stage it was, “Yeah, we’ve got to put a band together”. He actually suggested I come and join Black Cat Bones, his current band, but I felt if I was going to join another band and not start something new, I might as well stay where I was. I was all for starting something brand new.

And I had written one song, I had started to write songs, and I could see the potential there. I had written Walk In My Shadow, which appeared on the first Free album. And I also wrote Over The Green Hills, too. I started to write songs and I wanted to get a band together that was brand new. So we were all of the same mind; we were not going to do day jobs where someone would say, “Oh, I can’t do that gig, man, I have to be at work.” We were going to be totally dedicated to doing shows.

Paul Kossoff: The first real inspiration I had to get back into playing was seeing Eric Clapton with John Mayall [the Bluesbreakers included Hughie Flint on drums and John McVie on bass, who would ultimately join Mick Fleetwood in Fleetwood Mac] at a small club. I didn’t know who he was or what had gone down, but here’s all these people yelling, “God, God!” He really caught my attention and then I wanted to play. I found that my classical training had no bearing on that sort of music, other than dexterity.

After Clapton my interest grew. I went from him to Peter Green, to BB King and Freddie King, and then I got into soul: Otis Redding and Ray Charles [the same vocalists Paul Rodgers admired]. Green and Clapton were very dexterous and powerful at the same time; Clapton is everything I’d like to be. I also liked [singer] Long John Baldry, and [then Faces vocalist] Rod Stewart was good in those days, too. I saw the Jeff Beck band with Stewart and was very impressed.

Sandhe Chard: This little man knocked on the door [Paul Kossoff was about 5’3”] and he was in a long raincoat with a bunch of bootleg albums and he says, “Is my friend Simon there?” And I said, “Yeah, come on in,” and he played all his bootleg Jimi Hendrix albums. This little munchkin…

April 19, 1968. The four men who would go on to become Free convene for the first time to rehearse in a south London pub.

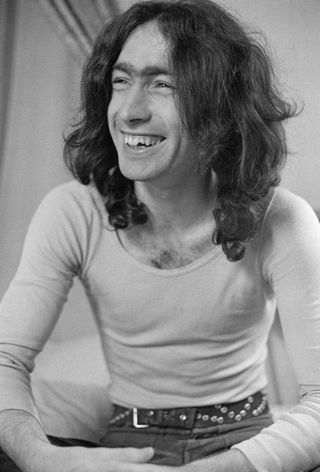

Simon Kirke: As I remember it, Koss and me met PR [Paul Rodgers] at The Nag’s Head some time in early 1968… We set our gear up and then got a shout from Andy [Fraser] who was downstairs. He had arrived in a taxi – very impressive – and wanted a hand with his bass gear. He asked for a receipt – something that would have escaped me and which was a portent for things to come.

He climbed the stairs and he set up his gear. In terms of rock history it would go down as a momentous occasion… In fact, we viewed it as a very successful beginning. Ideas were flowing between us. Koss and me were very pleased to be playing with such professionals. I remember Rodgers’ voice sending chills up my spine. This guy sounded like Otis. Like he was 40 years old. He also played exceptional harmonica, something he never really showed in Free.

Alexis Korner came in and stood at the back of the room with a couple of friends. He was all smiles. When we had a break we got to chatting. He knew Andy, of course, and Koss – PK was an on/off boyfriend of Sappho, Alexis’ daughter – but I had never met him; neither, I think had PR.

We needed a name for the band. After several hours together we knew we were going to be a band. Alexis had played in a group with Graham Bond and Ginger Baker which was called Free At Last. He suggested the name Free…

From the beginning we were a hit. The chemistry was just right. Released from the restraints of our previous groups we forged ahead. We used Andy’s mother’s house in Roehampton as a base. Every week we met with favourite albums and had a listening session. Hard to imagine now, but the four of us would lie around in Andy’s bedroom and play The Band’s Big Pink, Elton’s first big album, Otis, Revolver, Isaac Hayes’ Hot Buttered Soul and early Stones.

We once sat up into the early hours and wrote dozens and dozens of letters to club promoters stating our case as a worthwhile booking. Quite a few wrote back and said the name Free was misleading and patrons were liable to come around expecting free admission. It was too ‘arty’ a name.

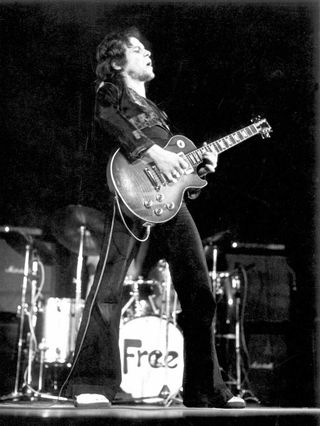

Paul Kossoff: Playing with Paul Rodgers helped me grow; he was my best teacher as to how to enhance a voice, blues-wise. I hate to play just solos; I prefer to hear his voice and back it up or rip it around or push it – without covering it over. My style and his grew up together.

I think my sound, especially my vibrato, has taken a long time to sound mature, and it’s taken a long time to reach the speed of vibrato that I now have. I trill with my first, middle, and ring fingers and bend chiefly with my small finger. I’ll use my index finger when I’m using vibrato.

I like to move people; I don’t like to show off. I like to make sounds as I remember sounds that move me. My style is very primitive but at the same time it has developed in its own sense. I do my best to express myself and move people at the same time. I think there’s still more room to develop in the way I’m playing. My vibrato is finally starting to grow up.

Paul Rodgers: We didn’t actually end up writing too many songs, Paul and I. When you look back, what happened was Andy was very keen to write songs and we threw ideas back and forth. We became the sort of Lennon and McCartney of the band in a way. We became the writing team. It evolved because we just had so many ideas to throw at each other. There were so many ideas that I think dear Koss got left out of the mix a little bit. It’s sad because I wish he was around today, I could redress that; we could sit and work some things out. Because he did have great ideas.

Free is officially a band, and Alexis Korner immediately asks them to support his band on tour. In 1968 they land an elusive record contract with Island Records, after a hard-fought battle to keep their ‘arty’ name. Of course, a record contract means that Free have to enter the studio sooner rather than later. The result is Free’s 1969 debut, Tons Of Sobs, but first they need a producer who will understand the band and their idiosyncratic way of working. They find one in the shape of Guy Stevens.

Paul Rodgers: There was no way on God’s earth that I would contemplate [the band name] The Heavy Metal Kids. I must admit the rest of the band did consider it because we were looking at the difference between having a record contract and not having one. It’s a heavy, heavy thing. You either change your name and you get a record contract or you don’t and you don’t get that record contract. And that was everything to us. But I stuck out for it and I’m glad I did really. Years later Island Records did have a band called The Heavy Metal Kids. They succumbed! [The HMKs were actually signed to Atlantic but they did record at Island’s Basing Street Studios.]

Simon Kirke: Chris Blackwell [owner of Island Records] wanted us to do an album pretty well right away and suggested Guy Stevens. Here were four young guys who were possessed of amazing talent and energy; we lived for playing and wanted nothing more than to be a world-class band. Guy was amazing. He was a sort of mad professor who put elements together and then sat back and watched the results. Actually, he didn’t exactly sit back so much as hurl himself around the place, interjecting ideas and observations. He suggested that all we should do was basically our stage set in the studio while the tape was rolling.

There would be the minimum of overdubs; it would just be an evening’s work. We did the album, I think, in two or three days. It was a pretty good showcase of where we were at that time. We were essentially a blues band with adventurous leanings.

Andy Johns: I really had a good time and they’d listen to me a bit. I came up with some arrangement things. I remember on The Hunter, for example, the Hammond part. That was a lot of fun for me.

And all the cross-fades, trying to be clever… I was very proud of that. They were so easy to work with because they were such good musicians.

So it was just me and them, and Guy Stevens was sort of the titular producer. Guy was mad, actually mad – very entertainingly, sometimes dangerously. He had no theory, he didn’t know an E string from a teapot but he really liked rock’n’roll music. Chris Blackwell really liked him because he was this really bizarre fellow.

Andy was the serious one and you could see he was the one in charge. In fact, word had gone out that he had sort of nailed Chris Blackwell for a really heavy-duty deal. People used to say funny things about Chris which I never understood because he was always very, very fair with me. So I was aware of that. Plus Andy’s style, he would play around everything, the bass drum. They used to make fun of Koss because he’d pull a lot of faces; he never combed his hair or anything, and they would laugh. Koss was a pretty sensitive chap and I think it used to upset him a bit.

Once the album is almost completed in late October, Free go back on the road in a flash. They hit the UK gig circuit alongside such luminaries as The Who and The Small Faces

Simon Kirke: We travelled all over the country, about 12 gigs in all. Big venues, 2,000-seater theatres. We went in our car while the gear went ahead in a van – quite a step for us. I will never forget the first night, seeing The Who for the first time. Keith Moon, 19 years old and virtually untouched by drink and drugs… imagine! And hearing The Small Faces – Steve Marriott’s voice, their total energy – we were humbled.

While driving up to Bristol, we were dozing or reading and we heard this car blowing its horn. Looking to our left, we saw The Faces, or rather three sets of buttocks belonging to them. Kenney Jones was driving to the gig that day, while the others were shining through an open window. Bless ’em.

Despite only releasing their debut in March, Free tour and manage to grab studio time to record their second album, called simply Free. By October 1969 it’s ready for release. In order to try to break the US market the band head across the Atlantic to support Eric Clapton’s post-Cream band Blind Faith.

Simon Kirke: We had completed the Free album and were scheduled to tour in America. We arrived at JFK [New York airport] and it was a trip; there were hostile looks from authorities. We had long hair and the Vietnam War was in full swing.

The first gig was a nightmare; the place boomed like a rail terminal. The crowd had come to see only Blind Faith. At one point, through a miscommunication, we were playing two different songs at the same time. I think Andy and I were playing I’m A Mover while Koss and Paul were playing Walk In My Shadow. After 30 minutes out of sheer frustration we left the stage. I walked through my drum kit; Koss trashed his amps. It was a mighty long way back to the dressing room.

Paul Kossoff: Clapton came up to me and asked “How the hell do you do that?” talking about my vibrato. And I said, “You must be joking!”

1970: Free are about to have the most exciting 12 months of their brief career, but unbeknown to them, it’s also the year that will spell the end. The catalyst for the success Free will enjoy comes courtesy of the Fire And Water album that contains the smash hit single All Right Now – a deceptively simple song – the inspiration for which comes from an unlikely source. The success of the song not only takes the band by surprise, but it catapults the quartet into the hearts and minds of rock fans worldwide.

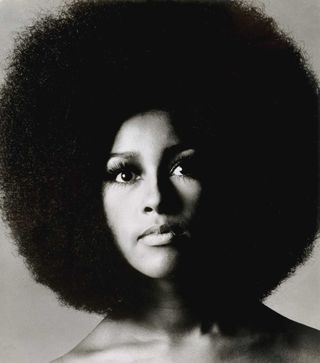

Paul Rodgers: It was pretty much a story I guess. I do remember the girl from Hair who went out with Mick Jagger. What was her name, that black girl from Hair [Marsha Hunt]? I used to live near Oxford Street and Hair was playing right there on the corner. And I remember seeing this girl standing there in the street and she may have triggered the idea for that, because there she stood, in the street, and she seemed to be smiling from her head to her feet.

Actually, I’ve never really said this before. People often ask me if it was inspired by someone and I usually say, “I don’t think so. It just came into my head.” But I was struck by her standing on the corner of the street. She obviously had a presence; do you know what I mean? Because there were a lot of people around and she just stood there and I thought, “Wow, look at her.” Something triggered in my head and I think it came from that.

Simon Kirke: I got a call from Island Records about 10 in the morning. Denise, our secretary, said, “You have to come in for a photo shoot, like now!” I knew that none were scheduled – this was a rare day off. There was also something in her voice so I said, “What do you mean, now?”

She said, “Your single has gone from No.30 to No.4 this week, you’re on Top Of The Pops tomorrow. I’m sending a car – get ready and look good.” Well, my voice just lit up and I thought, “Be careful what you wish for, it just may happen.” And that was the start of everything. Who knows where we would have gone had we not had that monster hit? The huge irony was that it was the beginning of the end for us – we would disband 18 months later.

Free have another album ready for release before the end of 1970 – Highway is recorded in brief moments of studio time sandwiched in between a European tour. On September 18, Paul Kossoff’s guitar hero Jimi Hendrix dies, dealing a major blow to the fragile guitarist. It’s the beginning of the end.

Paul Rodgers: That same passion and intensity that brought us together started to really work against us. Instead of imploding, we began to explode away from each other. It would have been good now, looking back, to have someone say, “OK, what you guys need is to take three months off and do whatever you want to do. Then come back together and talk about it.”

But instead we went phoooossshhh [mimics explosion] and it was almost too late. It surprised everybody how it affected Koss and how quickly he deteriorated. He just seemed to go. Part of the problem there was he moved into a place on Portobello Road which was just drug city. His door was right on the street and people would come up and say, “Hey, man, try this, try this”.

Right here, we began to feel we were losing control. There was this whole series of record covers suggested for the Highway album, none of which we used and some of which we liked. This record cover came out that we hated; it was suddenly there and I was very disappointed in it.

We had The Stealer and we had a very big argument between record company and band as to what was going to be the follow-up to All Right Now. They wanted Ride On Pony and we wanted The Stealer because we really felt it represented the magic and musicality of the band. It was one of the few records at the time that we actually wrote in the studio. It was so exciting for us and we were so behind it, and it failed. And I think that sort of kicked us in the nuts.

Andy Johns: Kossoff was out in the studio playing the riff from The Stealer, and we didn’t know what we were going to do because we only had eight songs. He was playing the riff, and it’s a great riff, and I said, “Well, let’s do that” and he said, “No, I don’t want to do that.” I said, “What do you mean you don’t want to do that? There’s a song, let’s do that.” He said, “Well, it’s not mine” which was ridiculous. So we had a bit of an argument and, of course, he lost because it just wasn’t logical.

Paul Kossoff: I don’t know, I guess I was starting to do more drugs. But with Hendrix it was all OK somehow. I really was totally into him. Highway didn’t do very well and I guess I was still maybe looking for my sound, like Hendrix had his sound. I was so influenced by Jimi and I was so affected by his death.

Simon Kirke: Our workload had taken its toll. Koss, dear, sweet, vulnerable Koss, a prodigy for Christ’s sake! Cocky, confident, bordering on arrogant, great sense of humour, good driver. Think of the Artful Dodger in Oliver Twist. He took me under his wing during Black Cat Bones and I was with him for five years after that off and on. I ended up trying to protect him from himself and the parasites around him but ultimately addiction won.

Andy was a genius. Quite simply a musical prodigy. His bass playing was in another league. But his talents didn’t stop there. He played great piano and drums. He had an unnerving habit of showing me a particular way of playing a song by jumping on the kit and bashing away. It drove me nuts – but he was usually right.

Rodgers was the intense one. Yes, he was aggressive and moody but that was only some of the time. On a good day he was charming and had a great sense of humor. He was also very wise – an old head on young shoulders really. And as honest as a long day. He was, quite simply, the best singer around. In all the years I worked with him, I never knew him to have a sore or hoarse throat. He hit notes that had dogs going in circles night after night – a complete and utter natural. Koss adored him. When we broke up, Koss missed Rodgers’ voice more than anything.

Paul Kossoff: His singing affected me in the best way. Not being a singer, my best teacher was Paul as to how to enhance, blues-wise, a voice. I hear his voice and I back it up and push it up or rip it around without covering it. I say that Paul is the best white blues singer you’ll find.

In May of 1971 Free splinter temporarily (an American tour supporting Mott The Hoople is cancelled, much to the chagrin of Mott mainman Ian Hunter), Kossoff and Simon Kirke join forces with John ‘Rabbit’ Bundrick on keyboards and bassist Tetsu Yamauchi to record a one-off album.

Rabbit: You can actually hear places where he’s losing it. Although I can honestly say that Koss was in fine form on most of the sessions. Of course there were drugs and booze around. We were young but the project [Kossoff, Kirke, Tetsu & Rabbit] breathed new life into Simon and Paul. They had basically just split up from what was in reality a marriage to Free. So, a fresh start did them a power of good. There were no signs with Paul of what was to come later on.

As it turns out, Free’s split is only temporary and the band re-forms in January 1972, releasing a new studio album, Free At Last, the following June.

Paul Kossoff: When you get to Free At Last, I think you have a real band called Free. To me, I think it was Free’s most complete album. Free was a great band, especially this one. All the later albums were great.

October, 1972. Free’s reunion proves to be short-lived, and the band continue throughout 1972 with an unstable line-up. Andy Fraser officially leaves the band in June (to be replaced by Tetsu and Rabbit), while the band’s summer tour of Japan is jinxed. Kossoff’s drug use renders him incapable of touring so Paul Rodgers takes over on guitar.

But that isn’t the end of it, upon arriving in Japan, Simon Kirke is diagnosed with a double-whammy of appendicitis and tonsillitis. The sessions for Heartbreaker – Free’s final album – later in the year are fraught. Kossoff is spiralling out of control (a session player has to be brought in to overdub guitar parts), and by December he quits the band and heads to Jamaica, ostensibly to work on a solo album.

Simon Kirke: Why weren’t we as big as Cream or Zep? I think had we stuck it out we would have become as big as them. Remember, we were very young and had only been together just over two years before the initial breakup. Cream’s members were in their mid-20s and Zep’s members were seasoned veterans – Jimmy and John Paul [Jones] had been in the session scene for some time before they formed the group. They weren’t dogged by drug problems either – that would come later.

W. Snuffy Walden: Paul didn’t like me much but it was an awkward situation. At that point, Kossoff’s drug thing made them have to track the songs with somebody else. Kossoff just wasn’t in any shape to be recording. So I was called in to do some specialty work and I wasn’t credited. They thanked me, but didn’t credit me because it was a band thing. I was a hired gun.

Heartbreaker is finally released in January of 1973. Free continue as a band and undertake an extended tour of the United States. The music press announce that Osibisa guitarist Wendell Richardson is Kossoff’s official replacement in Free. Kossoff goes to see the band play in Florida in February of 1973, but he spends much of the year recording with his new solo band, Back Street Crawler – the album is released in November 1973. Kossoff spends much of 1974 in and out of rehab trying to quit his habit – by now he was injecting heroin.

The following year he works with a variety of people, including sporadic dates with Back Street Crawler and time spent with veteran folkie John Martyn who endeavours to get him clean. It seems to work but unfortunately is only temporary and by the end of 1975 Kossoff’s old habits have reared their ugly head. In March of 1976 Kossoff and Back Street Crawler are touring the US; on March 18 the band take an overnight flight from Los Angeles to New York. It’s the last thing Paul Kossoff will ever do.

Terry Wilson: He had broken two different fingers, different times by falling down from overdosing. I walked into his room and he had a couple of his friends there that brought some barbiturates and some other stuff. I walked in and was so pissed at the girl who was there. Her name was Lesley I think, but went by the name of Dale. She said we, the band, didn’t understand him and his needs; I proceeded to tell her that there was a girl or guy in every town who said the same thing, who would go score him something just to get closer to Koss and hang with him.

A day later we were on the plane going to New York to play Atlantic Records the new album when Koss died – from the very drugs Dale or Lesley or whatever her name was scored for him. It turned out he had gotten heroin, valium and seconals from her.

Tony Braunagel: I can’t tell a romantic story, I won’t lie. We had a meeting the night before [the fateful plane journey] and there was some unrest. I remember him saying something like, “I don’t think I’m going to be playing with you guys when we get back to London.” And I’m thinking, “That’s strange, that’s really strange”. I knew that he was really loaded and that next night we left to get on the plane, I knew that he was packing drugs. He even offered me some of them.

We got on the plane and he was sitting next to me in the middle seat. I could feel the plane coming down in New York and I woke up and looked in the seat next to me and he’s not there. I looked at the road manager a few rows up and said, “Hey, Johnny, where’s Paul?” And he says, “I dunno”. That’s when the plane started coming down in New York City and I see people running up and down in the aisles. The next thing I know, the plane lands, they get everybody off the plane, and they get all the guys in the band over to the side. We find out then that they had to break into the bathroom. And he died.

Sandhe Chard: He went through a lot, and in those days it was tough. There was this bet as to who would die first – Chris Wood from Traffic or Paul.

Rabbit: I say that what tilted him over the edge was definitely the breakup of Free. That was his life, and he never understood why the other guys couldn’t get along and enjoy it like he did. Obviously it wasn’t their fault, and no blame can be assigned to anyone but Koss. You make your own bed in this world, and it’s up to you whether you sleep in it or not. I know the rest of Free had to just watch him fall apart, and that was hard for them. But it was beyond their power as mere mortals to fix the problem. Koss was sort of supernatural, not of this world.

Paul Rodgers: We always had a good relationship, Koss and I, and I loved him dearly. I wished and hoped that he would pull himself together to play. I miss him even now, he was a great player, and we had almost an esoteric understanding of each other’s space.

Sandhe Chard: That’s all I can tell you about him. He was an intellect, a great reader… His face when he played was… God. He went there. He went to places we don’t know.

Cast of characters

Tony Braunagel: Drummer, Back Street Crawler

Sandhe Chard: Girlfriend of Paul Kossoff

Andy Fraser: Bassist, Free

Andy Johns: Engineer, Free’s debut album Tons Of Sobs

Simon Kirke: Drummer, Free

Paul Kossoff: Guitarist, Free

Rabbit: John Bundrick, keyboard player during the latter stages of Free

Paul Rodgers: Vocalist, Free

W. Snuffy Walden: Session guitarist brought in to finish the Heartbreaker sessions

Terry Wilson: Bassist, Back Street Crawler