Tool aren’t so much a rock band as – to paraphrase Winston Churchill – a mystery wrapped in an enigma shrouded in a riddle. Then again, it’s kind of hard to be enigmatic when you’re down the pub. Lord knows, we’ve all tried.

Tool have spent years carefully cultivating an impenetrable cloak of occult conundrum around themselves. Their lyrics are dense, and loaded with gnostic and alchemical significance. Their music is complex and wilfully difficult. Frontman Maynard James Keenan never actually stands at the front, he lurks in the shadows at the back of the stage. “That set-up is purely for the sound,” he claims. “I don’t need to scream over the bass and the guitar to be heard. I need to hit some difficult notes, so I need as uncluttered a live sound as I can get.”

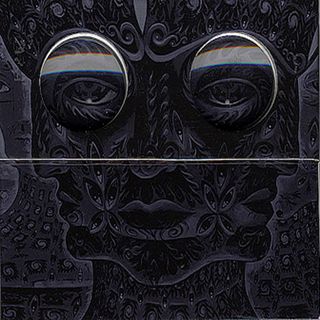

Tool often perform in total darkness, with the disturbing videos made by guitarist Adam Jones projected behind them. Their albums are the subject of a flurry of disinformation and rumour that usually has no basis in fact, though there remains a suspicion that the band themselves are responsible for their own gossip. They never used to give interviews and now, when they do, they dole out the information that everyone needs to know in small, tantalising doses.

What’s more, they never give the impression that any of this is at all deliberate, which makes them even more tantalising and enigmatic than ever.

But here they are in the upstairs room of a North London pub for a playback of their new album, 10,000 Days. Maynard wanders around looking a bit lost, drummer Danny Carey – an absolute giant of a man – glad-hands journalists, and bassist Justin Chancellor enjoys a beverage with some folks from the label. They just look like a regular band and not, as some Tool obsessive-types believe, the keepers of the keys to all the arcane knowledge which has puzzled humanity since the dawn of time.

Before the playback of the album, Maynard’s almost apologetic when he quietly announces: “Uh… we’ve done a bunch of new songs. Wanna hear them?”

The album begins and it’s magnificent. Difficult, but magnificent. Then, having sat through over an hour of this viscous, ultra-heavy psychedelia, Maynard then says, again almost apologetically: “Thanks for putting up with that.”

Tool, more than any other band, have been responsible for inspiring a new wave of hard rock that isn’t ashamed to call itself progressive. The term ‘prog’ still elicits sneers and lame jokes about wizards and elves. Yet the most important bands around at the moment are all, arguably, neo prog bands. The range of the new prog is immense and very diverse: from the emotional Mahavishnu Orchestra-plays-bossa-nova thrills of The Mars Volta to the snarling polar intensity of Opeth, they all, to some extent, owe something to Tool.

There are also hundreds of Tool impersonators, bands such as Mudvayne who seem to lurk in their wake, providing vaguely acid-tinged metal with a touch of the enigmatic and esoteric when Tool are in one of their now-frequent retreats.

“I don’t hear that,” says Justin Chancellor. “All the time I’m told that this band or that band are inspired by Tool but as one of the biggest fans of this band, I have to say that I don’t get any of the emotional feel from them that I get from Tool.”

They all agree, however, that they are big fans of The Mars Volta. Regardless of whether or not you actually hear the direct influence of Tool in these bands, they probably wouldn’t exist if Tool hadn’t been there first.

“I disagree. I think that they would still be doing what they are doing without us,” says Maynard. “You listen to At The Drive In [the original band that featured Mars Volta members Cedric Bixler and Omar Rodriguez] and they were setting themselves up for the next thing, that whole Santana jam thing.”

But you could argue that without Tool there wouldn’t be a mass audience for what they do.

“Yeah, but I think that when Radiohead in the 90s started doing these long introspective pieces, that also set the stage for The Mars Volta and for a lot of bands like them,” nods Keenan sagely.

“Radiohead are a band who just kept pushing things out and out, who took their success and used it as an opportunity to go further,” argues Justin.

Tool have often been lazily dubbed ‘the heavy metal Radiohead’, though whatever their roots and wherever they get filed in the record shop racks, you’d be hard pressed to describe Tool as a heavy metal band these days. They are unarguably heavy, and there are a lot of metal inspirations, from Zeppelin to Meshuggah, in their sound.

“I don’t think that we were ever a metal band,” says Danny Carey. “I can understand that maybe we’d get compared with Pink Floyd…”

“It depends what you mean by heavy metal,” argues Justin. “I always think that we’re a heavy psychedelic band.”

“Yeah, it’s all about language,” says Maynard. “So were Black Sabbath a metal band?”

Well, er, yeah. Of course.

“Oh, okay. But if Black Sabbath are a metal band, then I guess that we are, too. But when I listen to things like Master Of Reality, I hear sort of heavy political rock’n’roll. I guess I don’t really hear them as heavy metal.”

“Heavy metal just makes me think of Whitesnake,” says Justin.

Well, see, Whitesnake are really more hard rock than heavy metal…

An animated, lengthy and inconclusive discussion of what actually defines heavy metal follows, with Justin arguing that cult band TV On The Radio are real heavy music.

“It’s meaty, it’s really weighty shit, and I would compare us to something like that. It’s not heavy as a genre or anything but the effect is similar. It’s not about the types of guitars, it’s just how it was made.”

Maynard sighs, takes off his cap and runs his hand across his smooth pate. “Well, we’re certainly not a hair metal band,” he muses.

Tool have been a massively popular and influential band, yet their output over the past 15 years is sparse: four albums in 16 years, the last two with five-year gaps between them. They are one of the few bands who have been able to play the game on their own terms, dictating to their record labels rather than the other way around. Formed in Los Angeles in 1990 by Maynard, with guitarist Adam Jones and then bassist Paul d’Amour (who left in 1995), they were completed when neighbour Danny Carey, already an established pro drummer (he had played with Carole King, among others) was introduced to Maynard by Rage Against The Machine’s Tom Morello. He ended up joining the band by accident: “I felt kind of sorry for them, because they would invite people over to play, and they wouldn’t show up, so I’d fill in.”

Carey also recounts that he once heard Maynard shouting at another neighbour and thought there and then that he would have a great singing voice.

Their first EP Opiate and album Undertow were immediately dogged by controversy: the original cover featuring some rather ample naked women was withdrawn from chain stores across the US. Also, the Adam Jones-directed video for the single Prison Sex was deemed to be too graphic and was withdrawn from MTV. Despite, or because of, this, the album sold well, and enjoys double-platinum status at the time of writing.

The band’s reputation was cemented by a slot on the 1993 Lollapalooza tour. Their 1996 album Ænima was an altogether more complicated and adventurous record. Grammy Awards, big sales and massive stadium tours followed. Then things started to go sour; they were sued by their label Zoo after they allegedly started shopping around for a deal elsewhere. Tool counter-sued, claiming that the label had not exercised their option to renew the contract, and that the band were therefore free to go elsewhere. A stalemate ensued.

Then Maynard formed A Perfect Circle in 1999 and in the wake of the phenomenal success that the band enjoyed, people started to ask questions about the future of Tool. In interviews, Keenan maintained that Tool were still together and that a new album would be forthcoming, though he also hinted that all was not necessarily sweetness and light in the camp.

“We are definitely competitive people, so whether those guys will admit it or not, they definitely feel competitive,” said Keenan at the time.

The 2001 release of Tool’s masterpiece Lateralus and its subsequent commercial and critical success (they picked up their second Grammy Award for the song Schism) was a kick in the teeth for the received wisdom pedalled by marketing types that says that ‘young people’ have short attention spans and are incapable of engaging with anything – music, novels, films – with any depth.

Here was a 70-minute album with no perceptible tunes (certainly nothing that you could chop down into a ringtone), songs averaging eight minutes, no pictures of a pretty-boy band on the cover and lyrics written in Enochian, the language of the angels, supposedly spoken by Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. It sold shitloads and entered the US Billboard album charts at No.1. What’s more, when they toured with King Crimson that same year, thousands of these supposedly dim-witted, mouth-breathing youths with the attention span of goldfish concentrated intensely, not merely tolerating the complexity but actively digging it.

Tool make no concessions towards those who go along to hear their ‘greatest hits’. In order to transcend the mundane limits of the everyday, they require some commitment on the part of the listener. You have to be prepared to give them your full attention for at least two hours of your life. “I think that people are attracted to our integrity,” says Carey. “As I’ve said before, I think we’re an alternative band in the sense that we’re an alternative to what people normally categorise as alternative, which really all sounds the same. We’ve always had record companies and management who tell us that the way to do things is to tone the music down, make it more radio-friendly. But I think of bands like Led Zeppelin, who never went down that road yet were still immensely popular.”

They are also respectful towards King Crimson since the aforementioned tour: “We grew up listening to them and we were nervous following them. We thought, damn, everyone is gonna know where we stole everything from,” says Maynard.

In truth, though, Tool have gone way beyond any of their influences. They certainly don’t sound like King Crimson or any other band that they are compared with. They do, however, apply the same approach to their music as King Crimson; a band who – even today – continue to push forward. ‘Progressive’ has nothing to do with glittery cloaks, pointy pixie boots and twiddly pseudo-classical arpeggios and everything to do with, well, progress. Tool’s mission is simply to make music that has never been heard before.

It’s hard to actually recall anything very specific about individual songs, it’s all a broad sweep, but 10,000 Days is a phenomenal album. It seems loaded with meaning: Maynard says that the thing linking all of the songs is the intense emotional states that he was in at the time of writing and recording. The titles are packed with significance: according to some sources, the name 10,000 Days refers to Keenan’s mother, Judith Marie Keenan, who suffered a stroke that left her in a wheelchair for the last 27 years of her life. There are roughly 10,000 days in 27 years.

Wings For Marie (Pt 1) also refers to Maynard’s mother. The song Lost Keys (Blame Hoffmann) refers to Albert Hoffman, the chemist who synthesised LSD. Lipan Conjuring uses an Apache chant. Viginti Tres is Latin for 23, a number with a lot of occult significance. There’s so much there for the real shutaway web fanatics to spend the next decade tearing apart for significance.

It’s a more approachable album than Lateralus: there are tunes, the pace is slower and the songs more expansive. If Lateralus was their Atom Heart Mother then 10,000 Days is their Meddle.

There were initially some doubts as to whether 10,000 Days would happen, again not in the minds of the band themselves, but in the flurry of online speculation and rumour trading. The main source seems to be the continuing success that Maynard has enjoyed as a member of A Perfect Circle. While Tool worked on their last album, Maynard was off on tour with APC, enjoying phenomenal popular acclaim, and only returned in time to record his vocals. On 10,000 Days, however, he was there at the start of the writing process and returned at the end, though he spent the interim touring and recording with APC.

Tool are a democracy: ‘All Indians and no chiefs’ as it said on one of their T-shirts. All of them contribute to the writing of songs. All have a say in how the band is run. All bring in ideas. Although Justin replaced original bass player Paul d’Amour just before Ænima, it would be hard to imagine Tool surviving without Maynard. Not many bands/artists can sustain parallel careers, but George Clinton with Parliament/Funkadelic, Ozzy with the reformed Sabbath/solo career, and Mark Lanegan with his own solo career and Screaming Trees (until they split, obviously) and Queens Of The Stone Age spring to mind, so it is possible. However, APC are now officially laid to rest and while Maynard – and all the other members of Tool – still have extra-curricular musical activities, this band are going to be everyone’s central focus for at least the next few years.

“There are doubts every day when you wake up in the morning,” explains Carey, ”but there were no doubts whatsoever that we were going to make another album.”

Maynard, it has to be said, isn’t above helping the rumours along. Last April 1, he announced that he had found Jesus and was quitting music for good. When he was later contacted for comment, he said that he had in fact found Jesus but that: “He was a total punk!”

Tool love to fuck with their fans. They have an April Fool’s story every year that half of their fans end up believing to be true. Their official website hosts a monthly newsletter full of highly entertaining disinformation posted by their webmaster Blair. Over the past few years it has been revealed that Danny Carey’s drum kit is rimmed with gold from a melted artefact that they found at the mysterious Rennes Le Chateau in France; they regularly post fake track lists and bogus artwork to keep everyone guessing; and then, occasionally, they slip out something true and nobody believes them.

When confronted, they seem bemused that anyone else is bemused.

“It is what it is,” says Maynard cryptically.

There is a palpable sense of paranoia around the album, even to the extent that there were no advance copies available for the press to be able to digest at their leisure. To hear it, we had to attend one of only two UK playbacks at the aforementioned North London pub. Before doing an interview, we had to sign a contract that effectively gives them the rights to our first born if a single word or image leaks out before the May 1 release date.

“It’s just really that we create our albums as a whole,” Danny Carey says. “We think very carefully about everything. The artwork on the packaging and the videos are all an integral part of the album. We want to control the way that our music is presented to people. It’s not so much that we oppose things like downloading, but it takes control over the creative process away from what we do.”

“Once it’s actually released we’re not really too upset,” says bass player Justin Chancellor. “After that I suppose it all goes to spread the word…”

After the interview is over, we get to chatting about the changes that the internet has brought to the music industry. Carey is enthusiastic, foreseeing a situation in the near future when Tool will be able to make music without a record label to mediate between band and public.

But they are still possessive of their own creation. “The ones who get hurt by MP3s are not so much record companies or the business, but the artists, people who are trying to write songs,” says Maynard.

Although they come across as regular human beings, there’s still an air of enigma surrounding Tool that will probably never be blown away. As we leave, Justin – the band’s token Englishman – tells me that he’s going to watch Arsenal play Real Madrid in the Champions League on TV. We discuss the relative merits of each in a frank and forceful manner. (“Arsenal… faaagging kaaants!”)

“I’m going to watch,” admits Keenan. “My son Devo is an Arsenal supporter.”

Oh God. Rock’s most sphinx-like performer is a Gooner! Now that’s fucking enigmatic.

This was published in Classic Rock issue 94.