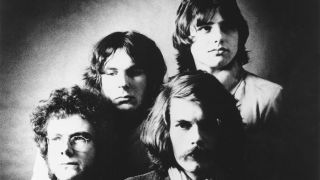

In the middle years of the 60s the big rock talents – such as The Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Beach Boys, Bob Dylan – had dominated the album chart, passing the top spot between them like members of a private club. But as the Swinging 60s moved through its autumn years and neared a new millennium, rock music was changing, coming of age, and entering a Golden Age that would shimmer with the dazzling luminescence of unprecedented creativity and diversity.

21ST CENTURY SCHIZOID MAN LIVE 1974

To record their debut, King Crimson had been teamed up with producer Tony Clarke, who had worked with the Moody Blues, including on their massive hit Nights In White Satin, and originally set up at Morgan studios in north-west London. After just a week, however, it was clear to the band that they and Clarke were not singing from the same songbook, and that the partnership was never going to give them the space to fully express and indulge themselves and follow their vision. It was also decided to move operations to Wessex studios which, situated in an old church, had a bigger natural sound. It’s where everything on the album was recorded.

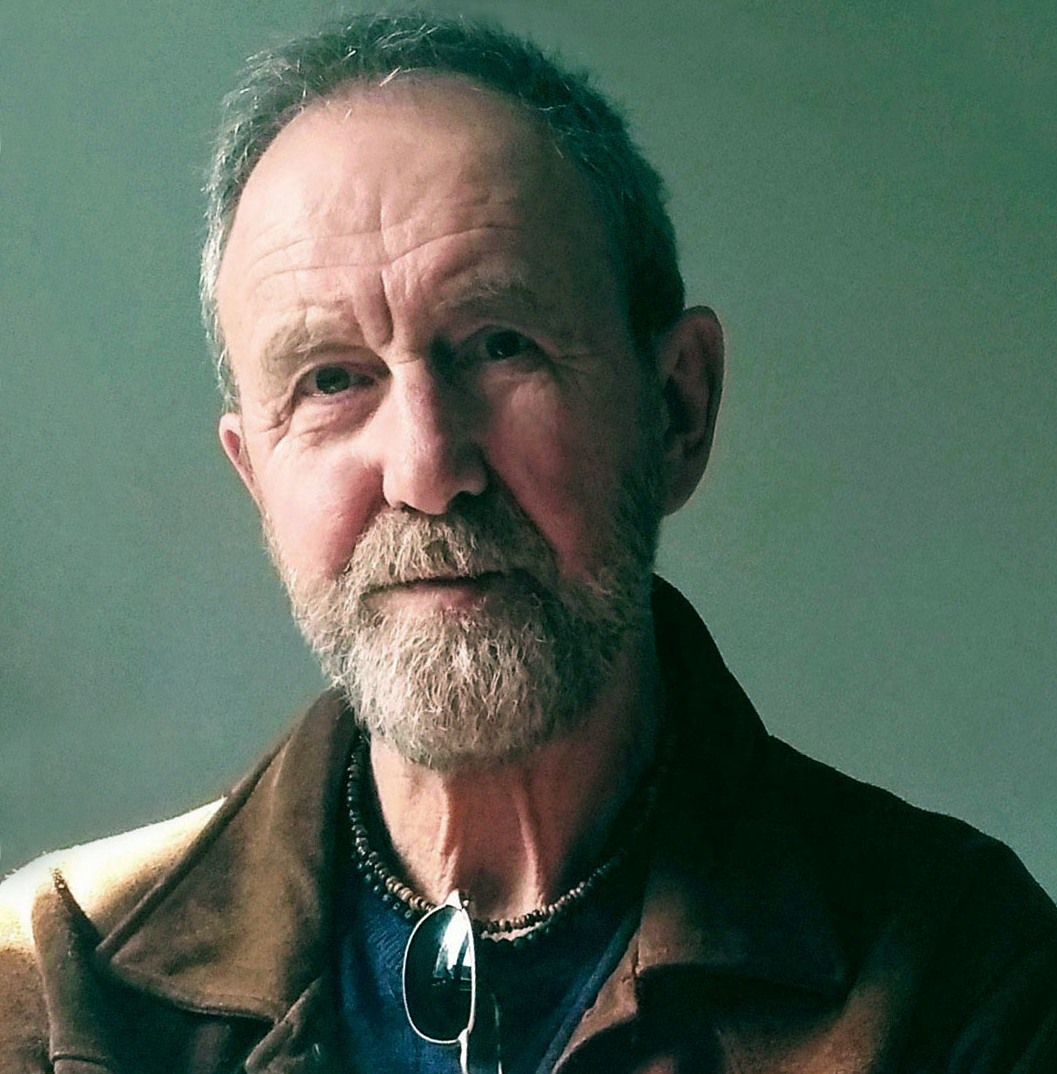

With Clarke out of the picture, it was decided that the band would produce the album themselves – something that was highly unusual for a first album by a new band. Given the technical capabilities of the band, though, producing themselves turned out not to be that difficult, according to the band’s lyricist and co-producer Peter Sinfield. “But we had these fantastic engineers at Wessex, who’ve never really had the plaudits they deserve,” he points out. “And it was a great studio, with lots of valve mics, which make a difference. It was all done on eight-track, so there was a lot of editing because it was a very fussy band.

“It’s such a blur, because it was so fast,” Sinfield recalls now of the mere days it took to record the album, looking back almost 40 years.

Crimson had rehearsed long and hard prior to entering the studio, and the songs’ structures had also been worked up while gigging intensively in the few months the band had been together. The songs they had, that is. A problem they would have to address at some point was that they had barely more than half-an-hour’s worth of music prepared. Live, they played a combination of originals and covers, but they were adamant that the album would be all their own work. The shortfall in material, however, didn’t seem to be cause for concern. “We were all 24, 25, 26, and we’d all been around for quite a while,” Sinfield says, “so we had quite a lot of ideas and bits and pieces to fall back on when the day came that they were required.”

Plus they were all very capable musicians, each with with more than one string to their bow. None more so that Ian MacDonald, who had been in the army and learned horn arranging, and could play brass and woodwind instruments as well as guitar and piano. “I remember when I first met him I thought I’d found Mozart,” Sinfield laughs. “He’s an unbelievable musician. Even to this day I don’t really believe that someone can play so many things so well. And the irony is that he only wanted to be Paul McCartney, really, and strum his guitar.”

With much bigger ideas than the budget and very limited time, there was no room for a meticulous piecing together to accommodate what the album might appear to be. “We went in and essentially recorded the tracks live, and embellished them from there, taking advantage of the multi-tracking – although we only had eight tracks,” MacDonald recalls. The recording was completed in 15 days of recording, between July 16 and August 15, with the band doing gigs between sessions. “We’d record and then go on the road for two or three days then go back to the studio. I’m surprised by the nonchalance that I see in the diary I kept. It was just so matter-of-fact.”

That the album was completed in 15 days is amazing. That its best-known track, frenetic opener 21st Century Schizoid Man, given its complexity and technical difficulty, was recorded in one take is nothing short of astonishing. But then none of the tracks took long, and everything came together with a speed and smoothness that belies the end result.

The only occasional spanner in the works was the then-new instrument the Mellotron (see below), which went out of tune if the temperature varied.

The Beatles had been among the first bands to use the Mellotron, on Sgt Pepper, and The Moody Blues had used the instrument extensively. But King Crimson’s In The Court… seemed to be awash with Mellotron, to the extent that it was one of the signature sounds of the album.

“It appears to be awash with Mellotron, because two of the big, sweeping orchestral tracks – Epitaph and The Court Of The Crimson King – are,” Sinfield offers. “But used, we’d like to think, sensibly. We didn’t just plonk down handfuls of chords, we’d record each note and put it all together, and try to pretend it was a bit more like strings than it really was.”

IN THE COURT OF THE CRIMSON KING

“I didn’t want to record the Mellotron in the same way that the Moodies had done,” says Ian MacDonald, the man who played it on the record. “So the way we used it was more aggressive, more majestic. And one of the ways I did that was just to blast the Mellotron through a double stack of Marshalls and put a microphone about 20 feet away.”

Over the years, perhaps because guitarist Robert Fripp has been the only constant member of the band, it is often assumed that he was, right from the beginning, the musical genius at the heart of King Crimson and also the man very much in the driving seat. Sinfield, however, points to another member of the band as the one pulling the strings during the recording of the album.

“I think the driving force was Ian MacDonald, really,” he says. “Greg [Lake, bassist/vocalist] wasn’t really capable enough as a musician, or even as a writer. Not that he didn’t contribute anything at all, because obviously he did. Fripp was very steady and Robert-ish. Michael Giles [drums/percussion] always wanted to do it as difficult as possible and as jazzy as possible. Ian was the one who just wanted to do anything that we could possibly do within the scope and yet still have people listen to it. And I was the one floating around the outside knowing we should have an extraordinary cover and without the name on, and stuff like that.”

During the making of the album, did the band ever get the feeling that they were creating something that was a little bit special, and unlike anything else that had gone before?

MacDonald: “I don’t remember thinking anything like: ‘Wow! That’s great’ or whatever. Except maybe with …Schizoid Man. I remember listening back to that and thinking: ‘What the hell is this?!’

“We weren’t the type of band to slap each other on the back. We were very reserved in praising one another or ourselves. We just did it and went on to the next thing.”

Sinfield: “Maybe at the end. When it was all finished there was a sort of glow of satisfaction – and relief. There was a feeling of: ‘Gosh, we’ve done something and it sounds really rather good, and we’re quite proud of that bit, and that bit.’ By any standards, there are parts of that album that shine out. And I think it has a timelessness to it as well – which I can tell you by the royalty statements even today.”

Tape That

The Mellotron’s place in prog rock, and some great uses of the instrument.

Bulky, heavy, ugly and decidedly unsexy to look at it might have been (especially the early models), but the Mellotron carved out its own niche in the progressive rock scene in the late 60s and early 70s, to the extent that it bacame arguably the signature sound in the genre, used extensively and popularised by the likes of Genesis, Yes, King Crimson, Barclay James Harvest, Pink Floyd, the Moody Blues, Focus, Tangerine Dream and countless other prog bands.

Manufactured in Birmingham, beginning in the mid-60s, the Mellotron is a keyboard instrument that works, basically, by playing tapes of pre-recorded sounds, the tapes driven across tape heads by motors triggered by pressing keys on the keyboard; imagine a bank of tape machines, with the ‘play’ button of each linked individually to the keys of a keyboard. Effectively, the Mellotron was therefore the fist sampler.

As with a tape recorder, any sounds could be pre-recorded onto the Mellotron’s tapes and ‘played’, but it was the factory-loaded ‘orchestral’ sounds that the instrument became known for, and which defined it. Pressing just one key of a Mellotron doesn’t sound either impressive or particularly ‘orchestral’, but hold down a big chord and the huge, fat, textured, unique sound produced is like some heavenly harmony of the spheres, quite unlike anything else – perfect for the prog merchants looking for an otherworldly sound in which to drape their often equally lofty, bombastic, epic musical ideas.

Although the sound of the Mellotron became a huge part of prog it has also been used – albeit in far smaller doses – by bands right across the musical spectrum, including the Rolling Stones, The Beatles, Led Zeppelin, David Bowie and Lynyrd Skynyrd. Having largely gone out of favour after prog’s golden era, there has also been a revival in its use in recent years, with Radiohead, Porcupine Tree, Nine Inch Nails, REM and Opeth rediscovering its unique and evocative sound (check out www. planetmellotron.com). The following tracks chosen by Classic Rock Presents demonstrate some of the best uses of Mellotron…

Focus

Le Clochard (Moving Waves, 1971)

Sumptuous use of the Mellotron on an equally sumptous chord sequence, creating a huge, highly evocative orchestral/choir backdrop on which Jan Akkerman paints some stunning guitar work.

Genesis

Watcher Of The Skies (Genesis Live, 1973)

Any one of a number of Genesis tracks demonstrate the band’s textbook use of Mellotron: put together its big, fat sound, a great song, lush chords and an evocative melody and you have the sound of prog personified.

Gracious!

The Dream (Gracious!, 1970)

A relatively unkown band and track compared to the others here, from a surprisingly unsung 70s prog band who used Mellotron excellently to punctuate this 16-minute epic in particular with some majestic sounds.

King Crimson

The Court Of The Crimson King (In The Court Of The Crimson King), 1969)

Awash with Mellotron, but with a more aggressive, more ‘grimy’ sound than usual, this is one of the all-time classic Mellotron tracks, from one of the pioneering users of the instrument, and showed the rest how to get the best out of it.

The Moody Blues

Nights In White Satin (Days of Future Passed, 1967) One of the earliest tracks to feature heavy use of Mellotron, and still a stunning demonstration of the instrument’s evocative power when applied to a great, classic chord sequence and a soaring melody.

Radiohead

Exit Music (For A Film) (OK Computer, 1997) Subtle use of Mellotron rather than awash with it, but the instrument is a key element in the wonderfully spacious, panoramic sound of this track.

King Crimson on …The Crimson King

Track-by-track: an observation by Michael MacDonald and Pete Sinfield.

21ST CENTURY SCHIZOID MAN

MacDonald: “The first track on the album was the last one we actually recorded. And I’m very fond of letting people know that we actually recorded it from beginning to end in one take, with no edits. We did overdub some parts later. Contrary to what you might think, it was actually a breeze compared to other tracks. The sax solo just ends abruptly, but we needed the tape track to punch in for one of Robert’s guitar parts.”

Sinfield: “The lyrics for …Schizoid Man were written right at the end, where we knew the thing was angry, against the Vietnam war; an angry, modern song of its time. I knew I had to say something, and that I didn’t have many words to say it in. I remember writing the lyrics in the park near the cemetery in Fulham Palace Road.”

Ian MacDonald: “The second track we recorded. My original demo was a little bit more up-tempo and had some guitar strumming, but we changed the arrangement once we got into the studio. One thing I’m pleased with is that I managed to pull out a pretty nice flute solo at the end, under relative pressure. I actually did two and we put them together. You can hear where it goes from one to the other, but that didn’t bother me.”

Sinfield: “It’s got some beautiful guitar sounds by Robert – very tricky. Mike’s little pings like water dropping on the cymbals. The vocals are lovely. It was everything it should be. I knew at the time that that track was special, because it was just so moving to listen to.”

Sinfield: “Epitaph was a poem that I’d written when I had my own band. It started with the words, and then it was very much a piece of ensemble writing. Ian would come up with an idea, then someone else. I think Greg came up with the idea: ‘But I fear tomorrow I’ll be crying,’ which is very Greg-ish.”

MacDonald: “For some reason, getting that track right eluded us. Epitaph took about 10 hours to put the basic track down down – I made a point of noting that down in my diary. But I think it was worth it because, to me, that’s one of the best tracks on the album, if not the best.”

MacDonald: “We’d run out of material. And we didn’t want to put a cover tune on our first album. So we were left with a gap; we needed another seven to nine minutes. So once we’d recorded the basic track [the front section, with the vocals], Mike, Robert and I went back into the studio, set the tape rolling and just improvised for about 10 minutes. And I think it’s alright.”

Sinfield: “Greg really doesn’t play on Moonchild. That sort of free-form improvisation was never Greg’s bag. He was: ‘What’s all this twiddling about? Oh, I suppose I’ll have to put a bass note here.’ He just said: ‘I’m not playing on that.’”

THE COURT OF THE CRIMSON KING

The lush-textured, panoramic, epic title track that closes the album was actually the first track the band recorded, on July 16. Hearing this huge, gothic, densely orchestrated piece, it’s almost impossible to believe that it was originally “a sort of Bob Dylan song, if you can imagine that”, says Sinfield. “Ian took it and rewrote the music. He’d studied harmony, he’d studied orchestration, so his references were not just The Beatles, but also big, sweeping things like Stravinsky, Mahler, things that were emotional. And that would come out. That track did take quite a while to pull together.

“I was sort of worried about the vocals. They recorded line by line and dropped in. I probably shouldn’t say that, but there you go.