“The best gigs Traffic ever played were to absolutely nobody at all, apart from a few cows and sheep and the odd mate.”

Steve Winwood is sitting in a room at the Covent Garden Hotel sipping decaf, eating biscuits and reminiscing about that most English of albums, Traffic’s 1967 debut Mr. Fantasy – the one that started the trend for ‘getting it together in the country’, man.

As a statement in the music press, announcing the band’s formation explained: “We’re past the blowing stage and ready to work.” Far out.

In April that year, Traffic – Winwood, Jim Capaldi, Dave Mason and Chris Wood, four friends from the Midlands – became the first white rock act to sign to Chris Blackwell’s Island Records. Previously the precocious singer and keyboard player in the Spencer Davis Group, Winwood was already a chart star. “He was Ray Charles on helium,” according to Blackwell.

But the SDG’s attempts to recreate Tamla Motown star Junior Walker were frustrating Winwood. “I’d been obsessed with copying R&B, but we were regurgitating Atlantic sounds,” he says. “Since no one had really heard of Buddy Guy or John Lee Hooker we got away with it on the underground scene, but I realised I was never going to sound like those blokes really and I may as well be myself.”

After the Spencer Davis Group remixed their Gimme Some Lovin’ with Mason and Capaldi singing on the chorus, Winwood put away his Ray Charles act on follow-up I’m A Man, quit the group, and Traffic were born.

“I was a pop star so I became Traffic’s MD [musical director] and leader, which eventually made Dave Mason very angry,” Winwood explains. “The first thing we did was the theme song for the film Here We Go Round The Mulberry Bush which we were supposed to be in. Then Blackwell suggested we move out of London to the Berkshire Downs, where his friend had just the place for us.”

The four youths were given the keys to Sheepcote Farm, a cottage in the parish of Aston Tirrold. It was a desolate, two-storey house at the end of a long mud track on the Berkshire estate of Sir William Pigott-Brown, a 26-year-old part time jockey, full-time stud owner and leading member of the Swinging 60s aristocratic elite. “There was no running water, there was a well, and no electricity,” says Winwood. “Blackwell took the gamekeeper’s cottage down the lane so he could make sure we rehearsed and wrote material. It was a place where we could make as much row as we liked – and we certainly did.”

In those days there were two sorts of LSD in Britain: pounds, shillings and pence (lsd) and the lysergic acid variety: Traffic had plenty of both. Winwood describes their lifestyle as “like four students living on top of one another, surrounded by filthy crockery and unmade beds.”

Traffic’s first stab at success was the sitar-strung Paper Sun, a psychedelic would-be classic of the early Summer Of Love. To earn pin money they also knocked off a jingle for an ersatz orange juice drink called Zing!

“We didn’t have many run-ins with the locals,” Winwood recalls. “There was a gamekeeper called Dave Dick who walked round with a shotgun and didn’t like us at all. ‘You’re disturbing my pheasant and partridge with your ruddy racket!’. Pigott-Brown loved having a rock group on his spread. We used to go up to the big house and be the talking point among all the Sybillas and Ruperts. It was far more decadent there than in our place.”

Indeed there were dark tales in the village of orgies ‘up at the stud’, but Traffic didn’t even have girlfriends in tow. “Girls wouldn’t come to Sheepcote, if they had any sense,” Winwood laughs. “Cos if they did they had to do the washing and cleaning and it was an awful pigsty.”

Drugs were par for the course, and Traffic’s mates Albert and Twitch were sent off to London for supplies. Although Winwood says the band only took acid a few times, Jim Capaldi remembered life at the cottage as “very strange. The house had a powerful presence. You’d wake up and hear the sound of footsteps going in one direction. Friends would run out into the night totally spooked. Apparently a local boy had hanged himself in the well and his spirit haunted the place.”

Dave Mason, now living in California, doesn’t recall ever seeing the ectoplasm: “The only ghost I saw was my own face in the mirror the morning after the night before. I loved it there for a while. We were country boys anyway, and we lived like gypsies. We didn’t give a damn, just looned around. When you’re 19 pretty much everything is idyllic. By June we’d put in electricity and water, and built a concrete stage outside so we could play in the sunshine and enjoy the psychedelics.”

Mason was busy. He wrote Traffic’s biggest hit, Hole In My Shoe, after a druggy dream. “It was the first thing I ever wrote on my own. It was just a beautiful fantasy tune that got to number two in England. I liked it. Okay, it wasn’t the greatest song, and the others didn’t care for it much. There was already tension because Jim and Steve were working together, whereas I preferred to do it alone. But so what? We were supposed to be under the same banner. At the time, it wasn’t meant to be the single, but they all said they liked it and Stevie thought my voice was suited to the song.

“Eventually it just fell apart and there was no place for me any more. I was majorly ostracised. It was a shame, because I’d known Steve quite a while. I’d even been a roadie for Spencer Davis.”

It became apparent during rehearsals for the Mr. Fantasy album that cracks were appearing in the rural idyll. At the time, Winwood praised Hole In My Shoe. “It’s much better than Paper Sun,” he said, “more immediate. You can catch it at once.”

Or maybe he was being diplomatic. He now says the song “started the long falling out with Dave. The original idea was we would write together simultaneously. Whereas we made contributions to each other’s songs, he didn’t. He came out with that horribly commercial record of Hole In My Shoe, which was not and never was what Traffic wanted to be. To be fair to Dave, he was a very good writer, but he wasn’t on our wavelength. The record company loved it though, because it brought in revenue. That caused a major rift. We didn’t think it represented Traffic. It was too glib and twee.”

Capaldi later claimed: “Dave wanted us to jump into his psychedelic swimming pool but we didn’t want that. I suppose we took the piss. We could be quite abrasive. But our playing on the stage was great.”

Winwood agrees: “Those were the best times – the four of us playing live [outside the cottage]. The Hammond organ sounded amazing and the drums were perfect. We rigged up a generator, and had a light show borrowed from Zoot Money’s Dantalion’s Chariot, with oil slides. I’ve got the tapes somewhere. I should dig them out.

“Anyway, that’s how the album was done. Jim and I used songs like Dear Mr. Fantasy as a vehicle for jamming. Jim would jot down lines of lyrics on scraps of paper and old fag packets. He never had a notebook. Chris Wood, who was the most technically minded, was in charge of the reel-to-reel stereo tape machine – cassettes hadn’t been invented – and we’d busk along until we felt the urge to sing. Then we’d listen to it all back at night over smokes and decide whether it was good or rubbish. That’s how it happened.”

Mixing together a pleasingly English ragbag of psychedelia, blues, folk and classical, Traffic’s sound evolved by accident, although Chris Wood was a major influence on the group philosophy. It was Wood who insisted the others join him on bird-watching and star-gazing trips, and Wood who organised Traffic days out to walk the Rollright Stones and frolic on the White Horse at Uffington. A keen lover of the outdoors and the arcane, the thoughtful Wood also came up with the Traffic logo – the Celtic fiery cross that kept many a hippy occupied of an evening.

One day in May Traffic returned to London for a photo shoot with an American woman called Linda (Linder) Eastman. One story has it that while they were in town goofing around for her lens, Paul McCartney turned up clutching a copy of the newly finished Sgt. Peppers Lonely Heart Club band for all to marvel at. Paul left the album with Traffic and departed with the photographer.

Back at Sheepcote, what would become the Mr. Fantasy album was simmering along. Songs about their rustic environment included Berkshire Poppies, and Mason’s House For Everyone that began ‘My bed is made of candyfloss, the house is made of cheese’ and referred to Aston Tirrold as ‘The village is a pop-up book, the people wooden trees’.

Man, that was some strong acid. One day in July a gang of Teddy boys from Didcot decided to pay the long-haired freaks a visit but were seen off by gamekeeper Dick and a couple of Pigott-Brown’s tastier stewards. More welcome visitors were Steve’s pop star pals, such as Eric Clapton, Pete Townshend the Small Faces and Eric Burdon. “I don’t think many of them stayed the night,” says Winwood. “There wasn’t much to eat. We seemed to live on a diet of jam sandwiches, Weetabix and muesli and whatever we could scrounge from the big house if we had the munchies.”

Being Midlands boys, Traffic certainly liked the old weed. Winwood now sees that as “one of my downfalls. I smoked far too much dope and wasted a lot of my life, but during that period I wasn’t excessive. I was totally into the cottage-industry aspect of the adventure. Sometimes we’d go to the local pubs in Aston and sup a few pints. Chris liked chatting to the locals; I was pretty shy and antisocial. I remember once going to the Boot when we all had heavy colds and an old crone made us a concoction of onions and honey. ‘Git that down yer’. It was a real witches’ brew.”

In August 67 Traffic were ready to pack up their tape reels and head off in their jeep to Olympic Studios in Barnes, south London, to start recording the album with 25-year-old producer Jimmy Miller from Brooklyn.

“Jimmy spent a few weeks at the cottage,” says Winwood. “He’d already produced Spencer Davis and we all loved him. He was very important to Traffic, a very talented ideas man. He’d recorded in America where the technology was ahead of Britain. He also had quite different musical tastes to us. He’d been a cabaret crooner in a trio in upstate New York singing Frank Sinatra songs in supper clubs, so we took the mickey out of him. We’d stop our songs and break into old standards just to get him going. But he had a wonderful way of creating enthusiasm for work. He was clever enough to see beyond our naiveté. In the cottage we’d play him a tune and he’d stand there twirling the ends of his moustache, and then suddenly crystallise an arrangement. The art of the producer is very complex but Jimmy had it nailed.”

Engineer Eddie Kramer worked alongside Miller before the two men went off to produce Jimi Hendrix and The Rolling Stones respectively. “Jimmy was a vibes merchant,” Kramer recalled. “On Dear Mr. Fantasy he got annoyed at the awful, draggy tempo, so he jumped on the drum riser rattling a pair of maracas and made them change up to double speed. That made the song. His thing was: ‘How can I make you hear this song properly, hear it the way I’m feeling it?’.”

During the early weeks of recording at Olympia, Mick Jagger dropped by to hear Traffic and was so impressed that he took Miller aside and signed him up to work on the Stones’ next album, which became Beggars Banquet. “Jimmy took our percussive piano sound with him,” says Winwood. “You can hear it in Nicky Hopkins’s playing with the Stones. That came from us. But we didn’t mind at the time. It felt like we part of the same surge.”

After recording, Traffic often joined in the all- night parties at rock-star hang-outs like the Scotch of St James and Bag O’Nails. At Blazes, Mason befriended Jimi Hendrix, who would soon get him to play bass on All Along The Watchtower. Fellow musicians were intrigued by the young upstarts from Evesham and Brum, and a typical night found them in the company of heavyweights like McCartney and Brian Jones.

After a brief tour of Sweden to break them in, Traffic were anxious to unveil in England. Paul McCartney suggested they play at the Saville Theatre on Shaftesbury Avenue, which had been run by the recently deceased Beatles manager Brian Epstein and was still under his company NEMS management. It was announced that Traffic would play on Sunday September 24, on a bill with Wynder K Frogg, Nirvana and Smoke. In the spirit of the times, Chris Wood built a ridiculous quadraphonic PA, which didn’t function properly, while the band manoeuvred around a stage littered with the props from the production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream which was on in the week. To make himself feel at home, Mason went to Hamley’s toy shop and bought a selection of dolls’ heads he painted red and green (Traffic colours) to decorate the amps.

The audience was a mixture of recent Winwood fans and pop gentry: Brian Jones, Zoot Money, John Mayall, the Herd, Keith West, the Hollies.

In the stalls an exceedingly drunk Noel Redding shouted friendly abuse. Island Records boss Chris Blackwell looked on in admiration as Chris Wood dedicated Dear Mr. Fantasy to Frank Zappa, and Capaldi made a bizarre reference to England’s World Cup-winning squad member Nobby Stiles.

“The London debut wasn’t entirely successful,” says Winwood today. “The PA didn’t work too well and we didn’t really have an audience – how could we? There was no album out yet. We were on the eccentric periphery. I drew a crowd because of my past, but most people came out of curiosity. We played the entire album. But I refused to do any Spencer Davis crowd-pleasers, which didn’t go down too well. That was a big no-no for me.”

Traffic’s direction was moving fast now. They divided their time between the cottage and their London flats – Winwood’s in Westbourne Grove, Wood, Capaldi and Miller partying hard on the Crowmell Road, and Mason in Soho with his collection of robots.

“I was ready to leave at that point,” says Mason. The first album didn’t come out until December and we were working on the second record. The songwriting was becoming like a pitching contest and I knew I was losing out. It was a real shame because it started out so idealistic, no cares and no worries.”

Capaldi would recall Mason’s increasing dissatisfaction at the mood in the camp. “He knew we hated Hole In My Shoe, so one day he came in and said: ‘Well, what do you want, then? If you want groove I’ll give you fucking groove’.”

Mason then played the others his new songs Feelin’ Alright, You Can All Join In and Cryin’ To Be Heard, all of which were all blatant messages of his annoyance. “We were impressed, though,” said Capaldi. “They were great songs.”

In late October Traffic played at Newcastle City Hall on a bill with The Who, Marmalade and the Tremeloes. Mason quit the group shortly afterwards.

“The pressure got to me. I didn’t deal with our instant success at all well. I’d made the decision ages before but I did return to complete the second Traffic album. It didn’t have the same bare-bones excitement, but the songs were more mature even if it felt a bit like business rather than pleasure. Still, that era kicked everything off for me, so I regard it in a positive way. There were problems, for sure. But, hey, life has to move on.”

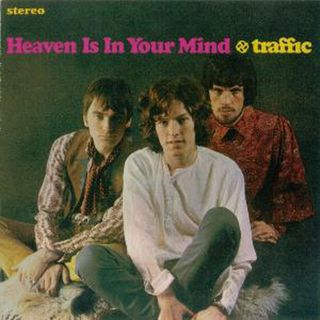

The year 1967 ended with the release of the Mr. Fantasy album and the belated Here We Go Round The Mulberry Bush single both making the UK Top 10. In the US the album was released under the title Heaven Is In Your Mind and with a different cover – Traffic as a trio without Mason, which was harsh to say the least.

“Well, we were very young,” says Winwood. “Certain things were regrettable. Still, it was a great time and a wonderful place to be when the sun was shining,” he says of the cottage. “Not so great when you had to build a fire on a foggy morning and trudge through the chalky mud. A few months later our lease ran out and we were evicted. We’d only been paying one pound a year! Pigott-Brown had to sell up and went to South Africa. So we all moved back to London.”

Today the cottage at Sheepcote Farm is still there, although now it’s in Oxfordshire. If you listen carefully on a summer’s afternoon you can hear the sound of Berkshire Poppies drifting across the fields of barley. It’s a quiet and beautiful place. There is no other traffic noise at all.

This was published in Classic Rock issue 147.