As the razzed-up 1980s arrived like a drunken gatecrasher at the ebbing party that was once the 1970s, the face of rock was changing. It was no longer embodied by the svelte, golden god, tousled mane framing a coquettish pout as he stood astride his mic stand. Nor was it the lead guitarist, swaying like a cobra, hypnotised by his own wasted elegance.

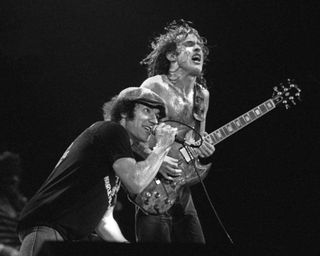

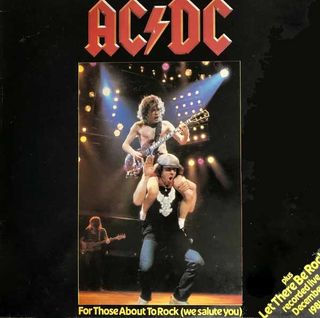

Instead, by the summer of 1981 the biggest noise in rock was being made by a 26-year-old man dressed as a schoolboy, complete with bad haircut, skew-whiff cap, and guitar turned to 11, sitting on the shoulders of a screw-faced, flat-capped singer with a voice that sounded like a giant gargling with nails.

Goodbye Led Zeppelin, their break-up confirmed the previous year. Hello AC/DC, whose latest album, Back In Black, had reached No.1 in Britain and sold more than five million copies in the US. It was an album with an appeal so broad that it would go on to become the second-biggest-selling of all time (after Michael Jackson’s Thriller).

Not that this was a story of overnight success. Back In Black was the seventh album AC/DC had released in six years. Moreover, it was an album that had been made in the aftermath of the drink-related death of singer Bon Scott, the irrepressible frontman who’d helped the band claw their way up from the bush-league of the Australian pub circuit to the theatres and halls of the UK and Europe, and now finally into the arenas of the beckoning world.

Against all odds, AC/DC had not only survived the hole beneath the waterline that Scott’s death represented, they had also positively thrived. With Scott’s replacement, Brian Johnson, on board, Back In Black, had succeeded beyond anyone’s wildest dreams.

“We knew that this new line-up would work, and that we wouldn’t have to worry about the past any more,” guitarist and co-founder Angus Young tells Classic Rock today. “We had found success with a new voice, and that was a big relief.”

Whether they consciously realised it or not, that success would change AC/DC. If the story of Back In Black was one of triumph emerging from tragedy, then that of its follow-up would be one of missed opportunities, ill-fated decisions, and the ultimate consolidation of the truth at the heart of AC/DC: that this was as much a family business as a band, and they didn’t need anybody outside of that family to tell them what to do or how to do it.

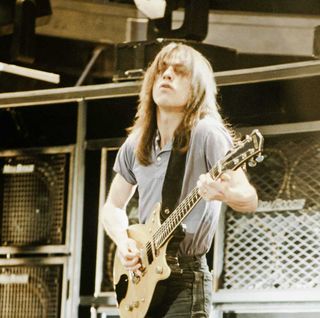

It didn’t start out that way. When the five members of AC/DC – Angus Young and his elder brother, rhythm guitarist and de facto leader Malcolm, plus bassist Cliff Williams, drummer Phil Rudd and new-kid vocalist Brian Johnson – arrived in Paris in the early summer of 1981 to start recording the follow-up to Back In Black, the building blocks for yet more success were solidly in place.

Not only had they managed the seemingly impossible in replacing Scott with Johnson, a 33-year-old journeyman whose only previous brush with success was a sole Top 10 hit with his former band Geordie seven years earlier, but also they had the ultimate team in their corner: top management in the shape of Leber-Krebs, who also handled Aerosmith and Ted Nugent; Atlantic Records, the world’s biggest label; and, most importantly, producer Mutt Lange, the man who had played such an important part in their rise. They even had a title for the new album that rang out as both a call to arms and a tribute to the fans who had elevated them to their current position: For Those About To Rock We Salute You. What could possibly go wrong?

“Of course, the label wanted it to sell just like Back In Black did, but we knew damn well that’s not going to happen cos you can’t do that,” Brian Johnson says today. “You can’t write songs with the intention to sell a million singles or albums. We never felt any outside pressure, because we didn’t let it in. We were very confident after the success of Back In Black. And we had every right to be.”

That’s not how everyone in the AC/DC camp remembers it, however. Ian Jeffery was the band’s tour manager at the time. He had been with them since they’d arrived in the UK in 1976 and was an integral part of the set-up. “We didn’t know it yet, but the really hard part had only just begun,” he says of the post-Back In Black period. “Everything was going great until Atlantic stepped in and fucked it up.”

Atlantic Records was one of music’s great powerhouses. Founded in 1947 by Turkish-born mogul Ahmet Ertegun, it made its name with R&B, jazz and soul before branching out into rock in the 70s, most notably with Led Zeppelin. The label had picked up AC/DC in 1976, though the feeling in the US office was that the band had little chance of making headway there. Hence the nudge they gave them towards ditching their original manager, Michael Browning, and switching in 1978 to more experienced handlers, in the shape of Leber-Krebs and the day-to-day attentions of an up-and-coming young firebrand from New York named Peter Mensch.

Hence also the decision to oust George Young – elder brother of Malcolm and Angus – and his partner Harry Vanda from the production hot-seats they had occupied from the very beginning and bring in producer-of-the-moment Mutt Lange, with the specific brief to produce an album that US radio would actually play (a feat he achieved in with 1979’s Bon Scott swansong Highway To Hell).

None of these decisions had been popular with the band, but they had gone along with them because they had no choice. “It was one of the only times they ever played the game,” says Jeffery. “The only other time was when Atlantic told them to go home to Australia and write a hit, and they came back with Rock And Roll Damnation, all hand-claps and maracas – and still not a hit.”

By the end of 1980, Atlantic had installed a new president, the hard-nosed Doug Morris. In Morris’s eyes, the success of Back In Black was a flash-in-the-pan. Rather than wait for a proper follow-up, he decided to make hay while the sun shone by releasing Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap – an album that had been released everywhere but the US five years before.

Phil Carson was the head of Atlantic everywhere outside America, and the man who had signed AC/DC to the label. “I said to Morris: ‘How are you ever going to consider releasing a Bon Scott album after we’ve just broken our balls introducing the public to Brian Johnson? I think you’re crazy!’” states Carson today. “There’s absolutely no doubt in my mind, if they’d waited for the next Johnson album it would have been an even bigger album. This was one of the worst money-driven decisions ever made by a label executive.”

Dirty Deeds… reached No.3 in the US, one place higher than Back In Black’s peak, but it sold only two million copies there at a time when Back In Black was now topping 10 million. The upshot, says Carson, was that the sales plateau for all subsequent AC/DC album releases in America would be similarly downsized. Not for the first time in history, short-term record company greed had stymied long-term artist career growth.

To their fury, the band didn’t have the power to stop the release, though they did their best to cover their record company’s tracks, claiming it was essentially to counter US bootlegs of the album. “There were thousands of pirate tapes, shit-poor quality and expensive,” Johnson told Creem magazine. “So rather they [the band] get the money.” When the album went Top 10, he added, without a trace of apparent irony: “I was more fucking chuffed about it than the rest of the band were.”

More chuffed than Malcolm and Angus Young. The brothers may have been slight in stature, but they more than compensated for their lack of physical presence with sheer force of personality – particularly the elder Malcolm, who had started the band as a teenager. “They would discuss things between them, but Malcolm was the decision maker,” recalls Ian Jeffery. “Even if Angus hadstrong points, Malcolm would be: ‘Fuck off, mate, we’re not doing that.’”

Even when Bon had been in the band, it had always been led by the brothers. “Bon was his own man, but the band belonged to Malcolm,” says Jeffery. “It was Malcolm who told Phil Rudd to stick to the beat; Malcolm who told Cliff where to stand and when to come to the mic. When Brian joined, it was Malcolm that told him to shut the fuck up between songs and just stand there and sing. It would always be Malcolm, every direction or turning they took.”

And they were about to take some that would affect their whole career.

On Monday July 6, 1981 AC/DC turned up at EMI’s Pathé Marconi studios in Paris to start work on the all-important follow-up to Back In Black. Having come off the road at the end of 1980 richer than they ever had been before, the five band members had enjoyed the first extended break of their career: Angus by settling down to married life in Holland; Malcolm and Phil Rudd, similarly, in London and Sydney respectively; Cliff Williams, meanwhile, had bought himself a “rock star hidey-hole” in Hawaii, where he had been joined, briefly, by Johnson, en route to buying his own new home in Florida.

But when they assembled in the studio, no one was particularly happy. Their mood wasn’t helped by the fact they had spent the previous week rehearsing at the Arabella apartments in the Montmartre – “which they all hated,” according to Ian Jeffery. It all was certainly a long way from Compass Point studio in Nassau, the Bahamas, where they had recorded Back In Black.

One familiar presence in the Paris studio was producer Mutt Lange, who had overseen both Highway To Hell and Back In Black. A multi-instrumentalist and songwriter from South Africa, Lange was a perfectionist who didn’t understand the concept of getting it right on the night. His penchant for repeated takes would reach its apotheosis with Def Leppard’s Hysteria, which took nearly two years of studio work to complete. Lange’s meticulous, borderline OCD approach to record production helped take AC/DC to the next level of success, but his methods were creating tensions with the band.

As always, the first point of order for Lange was capturing the drum sound, which he would use as the foundation stone upon which to build the rest of the album. Immediately there was a problem – and not just with the drums. AC/DC were a band built on spontaneity. Graham ‘Buzz’ Bidstrup, former drummer with Australian hotshots The Angels, who toured with AC/DC in the early days and worked in the same studio with George Young, recalls how “when they recorded back then they just did it like playing a gig. Bon would be grinning and giving it loads, drinking and sweating, and Angus would be flying all over the studio, rolling round on his back.” With Lange in charge, the studio was a very different place.

Mark Dearnley was Lange’s engineer on the Paris sessions. He had first worked with the producer and the band on Highway To Hell. “Mutt has a picture of the way he wants to hear it in his head, and will keep on bashing away until we hit that particular note that he has,” says Dearnley today. “And sometimes it can take some time. They spent the first three days in Paris just on the snare drum sound. It got to the point where at the end of day two Mutt said: ‘What do you think of that?’ I said: ‘I haven’t got a clue!’”

In the end it took nearly 10 days for Lange to decide he was never going to find the sound he wanted, and call a halt to the sessions. Another studio was hastily found. They spent the next two weeks trying out a number of different studios for a day or two each, before Lange decided that it all sounded better in the initial rehearsal room – a cold, stone room at Quai De Bercy, to where the producer ordered in the Mobile One portable recording studio from London.

The delays were starting to eat away at the band. Angus says that “probably most, if not all” the songs had been written long before they got to the studio. “We are always well prepared,” he says. “We go in the studio with complete songs and we know what we want. We don’t fuck around much. Unlike Mutt Lange. But that guy has always been slow – real slow. He’d need forever to get anything done. Otherwise it would have been in and out in a week, I’d say.”

Anyone dropping in the studio while AC/DC were recording wouldn’t have seen anything untoward. Johnson and the Young brothers spent much of their time perched on a large sofa, waiting for Lange to finish tinkering. “Bored shitless,” Angus says succinctly. Malcolm was even less impressed, pissed off at what he saw as Mutt’s “fannying around”.

Lange was also now questioning every aspect of the band’s operation, according to Jeffery. Added to his personal hit list, where Atlantic and Lange now vied for top spot, was the band’s management.

“[The band] felt that they were being compromised,” says Jeffery. “Stuck out in Paris they felt isolated. They were struggling with the record, to start with. They were starting to get into contentious situations with Mutt. It wasn’t flowing in the studio. They weren’t writing like they were used to. That whole side of things wasn’t happening.”

By now it was the first week of August – just two weeks before AC/DC’s first live show for nearly a year: headlining the Monsters Of Rock festival at Castle Donington. Though the date had been booked months before, this was not how the band saw themselves preparing for their biggest ever show in the UK. “We were shitting ourselves,” recalls Johnson. “‘Fuck, we haven’t played this! We haven’t rehearsed anything!’”

Their fears weren’t unfounded. Remembered now as one of those dreary, rainy days that disfigure so many outdoor British festivals, Donington 1981 also suffered from poor live sound and an under-par performance from the headliners, who relied on the same set they’d been playing on tour the previous year. Though the 65,000 fans there that day seemed appreciative enough, the band knew they had badly undersold themselves.

“It was just one of those days,” says Jeffery. “The BBC did something that buggered up the sound that we were getting blamed for. It rained and the band wasn’t really ready for it, even though the date had been in the diary for a long time before. It just sort of added to all the other things that were going wrong in Paris.”

Adding insult to injury, Malcolm had been stopped going up the ramp to the stage by a security guard for not having the correct stage pass.

Returning to Paris the next day the band, Malcolm in particular, was in vengeful mood. Somebody would have to pay. And that someone would be Peter Mensch. A former tour accountant for Aerosmith, Mensch had been appointed AC/DC’s key man after impressing them on their first US tour with Leber-Krebs at the helm, in 1979. Mensch had dutifully moved to London to be near the band, who were all now living there. “For the next two years Peter was their man every day – every day,” says Jeffery. “Hands on, totally.”

By 1981 Mensch was spreading his wings as a manager in his own right, signing NWOBHM rising stars Def Leppard while scouting around for more. “Peter can deal with five different bands at five different levels on every given day, easy,” says Jeffery. “That’s how he operates.”

With frustration mounting in the studio, Mensch was increasingly being seen as the enemy. “I think they felt Peter was becoming part of this big thing where the personalised things, the caring, were no longer there,” says Jeffery. “But Peter never stopped caring, believe you me.”

That wasn’t how the band – in particular Malcolm – were seeing it. Five days after their Donington appearance, AC/DC fired Peter Mensch. He declined to be interviewed for this piece, but did send the following message by email: “I was never told why I was fired. They called their lawyer, who called David Krebs, who called me. It was the Thursday after the first Castle Donington Monsters Of Rock show. And that is the only question I will answer.”

Looking back with the benefit of 30 years, Jeffery says now: “They just felt that Mensch was only turning up when it was time to give them more float [money], saying: ‘Why are you not done yet?’ He wasn’t being in sympathy with them and feeling what they were feeling. They felt a bit isolated and they felt they were being pushed and it was going wrong with Mutt, you know. It wasn’t happening in the studio and hadn’t been for a while. And Peter hadn’t seen that.”

Nevertheless, for Jeffery, who would effectively take over as the band’s day-to-day manager, it was a bombshell. “I told them: ‘I don’t think anything has changed with Mensch’,” Jeffery explains. “Malcolm’s like: ‘Well, it fucking has!’ At that point, you may as well just let him have another drink and go through the reasons why, you know. It’s done, it’s finished.”

Back in Paris, the same couldn’t be said for the album. The band were becoming increasingly bored waiting for Lange to put the finishing touches on take after take. “They would jam for hours just for the fun of it,” recalls Mark Dearnley. “I’ve got out-takes of Angus singing Feelings and stuff like that.”

While Angus Young now concedes that Lange “did a great job” on For Those About To Rock, Malcolm Young had already decided he’d seen and heard enough.

“The attitude was: ‘What the fuck are we paying this guy all this money for? We can fucking do it’,” recalls Jeffery. “It really soured when they started to look at the figures Mutt was being paid. They felt that they didn’t need him: ‘We write the songs and now we know what to do, we’ve done a couple of albums with him, game’s up, you know, we don’t need him any more’.”

For Those About To Rock marked the end of Lange’s relationship with AC/DC. The famously reclusive producer has never opened up about being dropped by AC/DC. In a rare online conversation, he merely commented that “Angus has a certain vision for his music, which works for him”.

“By the time we’d completed the album,” Malcolm says, “I don’t think anyone, neither the band nor the producer, could tell whether it sounded right or wrong. Everyone was fed up with the whole album.”

Listening back now, it’s not difficult to see why. Tracks like the pedestrian first single Let’s Get It Up, or the self-consciously scary Evil Walks, lacked the energy and wit of old. Double entendres had become single; riffs that had once been recycled were in danger of sounding tired and thin.

The only song that truly reached the same heights as the best songs on Lange’s two previous AC/DC albums is the titanic title track. Starting life as usual with a chorus and riff concocted by Angus and Malcolm, Johnson’s lyrical theme was supplied by a book Angus had come across about Roman gladiators. Its title, For Those About To Die We Salute You, was taken from the oath each gladiator would address the emperor with as they went into battle: ‘Ave Caesar morituri te salutant’ (Hail Caesar, we who are about to die salute you.) “We thought: ‘For those about to rock’,” says Angus. “I mean, it sounds a bit better than ‘for those about to die’.”

A journey song (in that it starts relatively slowly before moving through the gears towards a tremendous, all-guitars-and-drums-blazing finalé), its other signature motif was the sound effect of cannons blasting off as a prelude to its scorching climax – inspired by the cannons fired at the wedding that year between Lady Diana Spencer and Prince Charles. The band had been at the rehearsal room in Bercy when Angus noticed “the royal wedding thing” on the TV in the night manager’s office.

He picked up on the sound of the cannons, and a lightbulb went on in his head. “I just wanted something strong,” he says now. “Something masculine, and rock’n’roll. And what’s more masculine than a cannon, you know? I mean, it gets loaded, it fires, and it destroys.” So powerfully embedded would the image of cannons become that they even had one on the album’s sleeve, gifting rock one of its most iconic covers.

With the recording sessions finally wrapped up at the end of September, Atlantic hurried to get the new AC/DC album out in time for Christmas. Released in the UK on November 23, 1981, For Those About To Rock We Salute You was greeted warmly by fans and critics still basking in the heat of its mega-hit predecessor. It did not, however, follow Back In Black to No.1 in Britain, peaking at No.3 behind the Human League’s Dare and Queen’s Greatest Hits.

And while it did provide the band with their first US No.1 album, sales only reached the same comparatively modest levels as Dirty Deeds, much as Atlantic’s Phil Carson had predicted. Indeed, 30 years on For Those… has sold four million copies in the US – roughly 18 million less than Back In Black and, astonishingly, two million less even than Dirty Deeds…

So powerfully embedded did the image of cannons become within the band’s psyche that when the subsequent tour began in the US on November 14, along with the two-and-a-half ton Hell’s Bell that had first appeared suspended above the drums on the Back In Black tour there were now two dozen ‘cannons’ added to the stage show.

“There were 12 black boxes each side, in two rows of six that looked nothing like cannons,” Jeffery laughingly recalls. “Until they were lifted up from the ground behind the PA and barrels popped out – when they worked. Built by Light And Sound Design. Fire!”

The scene backstage had also changed significantly. While the band had never been short of female admirers in Australia and Britain – particularly the insatiable Bon Scott – in America AC/DC were now attracting the kind of high-heeled, spandex-and-boob-tube-clad groupies previously reserved for Led Zeppelin and the Stones. With most of the band now married, however, as Johnson told one US reporter: “You never fuck them. You shake hands and that’s it. That’s for the crew. They’re the ones with the passes, not us.”

It wasn’t just the groupies the band were now filtering out of their increasingly single-minded vision. More than on any previous tour, AC/DC now had things all their own way. With no Bon around for backstage visitors to enjoy a drink and a laugh with, the job fell to Brian and occasionally Cliff to keep the party fires burning. Which if you liked a pint and a roll-up they were good at. The days of running off with whatever group of hellraisers happened to come around town were long gone, though. They weren’t even keen to mingle with the other bands. “I like a nice cup of tea,” Angus would explain, “and a bit of quiet before the show.” Malcolm, it seemed, just liked to be left the fuck alone.

San Francisco rockers Y&T opened for AC/DC on the UK leg of the For Those About To Rock tour in September 1982. “Somebody told us: ‘Malcolm is a real hard-ass, so don’t say anything that’s gonna piss him off or you’ll be off the tour in five minutes’,” recalls Y&T singer Dave Meniketti.

More troubling in America were the renewed protests from a whole load of right-wing Christian groups, whose tanks had been amassed on the AC/DC lawns since Angus had been depicted wearing toy devil-horns on the cover of Highway To Hell. On one level, the “God botherers”, as Johnson called them, could be dismissed as just plain silly. He recalls a leaflet handed out by some Jesus freaks circling the environs of the Cabo Hall in Detroit where the US tour began, which claimed: ‘The Bible says the Word of the Devil is Evil and so is rock’n’roll’. “I don’t remember the Bible mentioning rock’n’roll,” he wheezed.

It was a story that continued to follow AC/DC throughout their US tour, with the self-avowed Christian Right citing new For Those About To Rock tracks like C.O.D. (an acronym not just for Cash On Delivery but also Care Of the Devil) and Evil Walks as more proof of the band’s devilish intentions. Even ostensibly more clued-up institutions like Rolling Stone magazine jumped on the AC/DC-are-bad-for-you bandwagon, describing them in their Record Guide as: “an Australian hard rock band whose main purpose on earth apparently is to offend anyone within sight or earshot. They succeed on both counts.”

Ask AC/DC now what they made of the Christian groups protesting outside their shows, and Brian Johnson is philosophical: “That was the best promotion we could get. We took them over from Sabbath, you know. They were probably the same people calling Ozzy and Geezer Satanists. I don’t know – maybe they were fanatics for hire.” “That’s right,” adds Angus sardonically, “they got paid by the hour.”

By the time the For Those About To Rock world tour reached Europe at the end of 1982, a year after it had begun, things were at last running more smoothly. Bernie Marsden, then guitarist with European tour openers Whitesnake, had been a friend of Bon’s in his party-hearty London days. “Things were different now, though,” he says, “you could tell.”

Apart from Johnson – “who’d you see at the hotel, maybe” – the other members of the band made themselves scarce outside the shows themselves. Marsden’s fondest memory revolves around what he calls “the legendary AC/DC pub” that would be erected backstage each night – to save the band from having to actually rub shoulders with real people in an actual bar.

“There’s a jukebox in there and a dartboard and a pool table. It even had beer on tap, with pumps and a barrel.” After their first show together, in Germany, Marsden recalls: “We finished, went down to the dressing room and got cleaned-up a bit, came back up, and they still hadn’t gone on. They were playing darts! Angus said to me: ‘Come on, you be my partner. We’re trying to get a double-eight to finish.’ While there’s 15,000 Germans going ‘A-C-D-C! A-C-D-C!’ Just going mad. And I suddenly realised we could have played an hour and a half and it wouldn’t have mattered one iota.”

Marsden made a point of staying to watch from the side every night. “I never realised until I watched it from that angle how much work Angus puts into the show,” he recalls. “Angus is wringing wet before he goes on. He gets himself really fired up. And then you’ve got the complete other side of it with Malcolm just locking it down, standing there cool as a cucumber.

“You never really knew what was gonna happen, even though the show never changed that much every night. Phil Rudd, every third or fourth song, instead of smacking his snare drum he’d smack his thigh. He’d got this permanent sort of never-been-able-to-heal-properly cut on his thigh, he’d hit it so hard with the stick each night.”

By the time the tour finally ended, in Zurich, two weeks before Christmas 1982, AC/DC had confirmed their status as one of the biggest touring attractions in the world – big enough to have turned down $1 million to open a stadium show in America for the Rolling Stones. “Malcolm had decided they weren’t ever going to open for anybody any more,” Jeffery recalls.

But while the tour was a success, For Those About To Rock We Salute You would prove to be a watershed for the band. Without the old team of Mensch and Lange to guide them, none of the next three AC/DC albums would get near the US Top 10. Indeed it was not until 2008 and the release of Black Ice that they reached No.1 again.

Letting go of Mutt Lange, says Ian Jeffery now, “was a huge mistake – the biggest mistake. It was really sad. With Mutt Lange they were crafted records, without taking away the spontaneity of it sounding like a band playing.”

The trouble was, for established figures like Mutt Lange and, before him, Peter Mensch (and, after him, Ian Jeffery, himself sacked in the wake of the commercial failure of the next AC/DC album, Flick Of The Switch) to be effective the band needed to cede elements of control. The problem was they were simply no longer prepared to do so.

From here on in, the world of AC/DC – the band that, during their formative years fronted by Bon Scott, had been an open invitation to all-comers to join in the fun; now, with Brian Johnson and everyone else doing as they were told by Malcolm and Angus – became a closed shop. Heads down, no-nonsense, not mindless but certainly no longer mindful of anyone outside their own inner circle. As Ian Jeffery says: “You’re either totally in or totally out with them.”

And the turning point was For Those About To Rock We Salute You, the flawed follow-up to one of the biggest albums in history and one that sealed the fate of AC/DC in so many different ways. Ask Angus Young the last time he listened to that record, and his answer speaks volumes. “I don’t listen to any of our albums – ever,” he says. “I mean, I’ve written and recorded them. Why would I listen to them?”

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #162, in August 2011