Early summer, 1969. Four young musicians are holed up in the basement of the Rolling Stones’ rehearsal room in south London. For the past few weeks, Ronnie Wood, Ian McLagan, Ronnie Lane and Kenney Jones have been jamming here, playing covers of recordings by American soul heroes like the Meters and the Bar-Kays and chiselling out a few instrumentals of their own. But there’s something missing: a singer.

Both Lane and Wood have taken turns at the microphone but it just doesn’t feel right. Guitarist Wood has already suggested his bandmate from The Jeff Beck Group, Rod Stewart, but the others aren’t so keen. Lane, McLagan and Jones are still reeling from the sudden end of the Small Faces, whose singer Steve Marriott walked out on them earlier in the year to form Humble Pie. Marriott had been a powerful, charismatic vocalist, but also a dominating force. The others don’t want to get burned again by a roaring ego. Wood assures them that Rod’s not like that. Cautiously, they invite him along.

Stewart is too shy to begin with, choosing to listen in from the top of the stairs. Then for days he sits silently on the amps, watching the quartet go through their paces. “We knew Rod from his time on the Immediate label,” Jones recalls, “so we knew what a great voice he had. He’d sit on the amps and just wait for us to finish playing at first. And every time we had a break we’d go up to the pub in Bermondsey Street to have a few drinks and a laugh. Then we‘d go back into the rehearsal room and play some more. That went on for a few weeks.

“Then one day I was sitting there playing, looking over at Rod and thinking, this just doesn’t make sense. So the next time we went to the pub, I asked if he fancied having a drink with us. Then I asked if he’d be interested in joining the band. He looked at me and said: ‘Do you think the others would let me?”

McLagan remembers Stewart getting up at the rehearsal place and trying something from Muddy Waters’s Live At Newport sing. That night there was a party at Alvin Lee’s flat around the corner. Jones floated the idea of Rod becoming a permanent member of their fledgling group.

“They were apprehensive about not getting another Steve Marriott figure, and didn’t want someone who’d let us down,” he remembers. “I totally understood what they were saying, but to my mind it was make-or-break time for us, and I felt it was the necessary thing to do. So enter Rod, enter lunacy!”

McLagan: “Once he started singing with us he was the missing link. He was just what we needed. Then it was all a lot of fun. And a lot of drinking.”

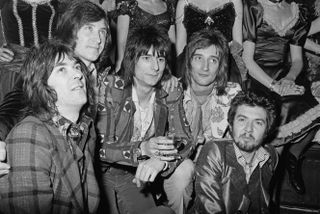

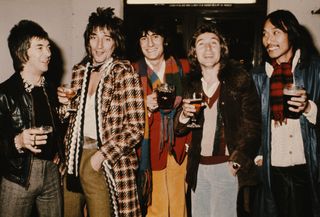

There was plenty of that, alright. The Faces, as they became known later that year, were the ultimate geezer band. A gang of peacock-haired ne’r-do-wells with the swishiest satin clobber and

the tunes to match. They swaggered and sauntered like no other band of the early 70s, strutting onto a stage like a bunch of rogues strolling into their local. Not for nothing was their 2004 box set titled Five Guys Walk Into A Bar… Gigs would invariably end with drunken renditions of We’ll Meet Again or When Irish Eyes Are Smiling, the five of them clustered around a single mic, before collapsing in unison onto the floor.

“It wasn’t just at gigs,” says Jones. “Everywhere we went we fell on the floor – airports, restaurants, hotels, bars. We were saying to people that you don’t have to take rock’n’roll too seriously. Every gig was like going to a party. The Faces were undoubtedly the most fun band I was ever in.”

But it wasn’t all beer and brandy. The Faces could really play, too. Their physical home may have been the nearest boozer, but their spiritual nexus was America, particularly Detroit and Memphis – the respective strongholds of Motown and Stax. Together with an insatiable appetite for southern blues and folk, the band played a unique blend of rivvum’n’raunch. At their peak they were a bigger draw in America than even The Stones. Had they been less cavalier and more inclined to stay on their feet, they might quite easily have overtaken them completely. But then such self-inflicted laxity is what gave the Faces much of their roguish charm to begin with.

In his intro to the forthcoming book The Faces 1969-75 – a sumptuous, photo-driven account of their brilliant, if brief, career – lifelong fan Slash contends that: “No band better exemplified ‘party band’ like the Faces, and no band has since. They wrote drunken, bluesy, cum-drenched rock’n’roll songs and delivered them with the ultimate ‘tip and a wink’ attitude… They’re one of the most iconic bands of all time.”

It’s a patent that many others have tried to emulate since, with varying degrees of success, from the Sex Pistols and Guns N’ Roses to the Black Crowes and The Replacements. “The Faces had some classic songs, but it was more about the feel of the band than anything else,” says Quireboys guitarist Guy Griffin. “Loads of bands have tried to replicate that. A lot of people have accused us of doing that. And I hold my hand up, because they were a big influence on me. I play the same Zematis guitar as Ronnie Wood, so I happily admit it.”

The Faces drew envy from their peers, too. One of their closest associations was with Free.“Touring with the Faces was wonderful,” says Free’s then drummer Simon Kirke. “They were at their peak and had Rod Stewart singing. Jeez, he could sing so well back then. He’s like Paul Rodgers, really; he never sung a bad show, he just had variations on brilliant. They always had such fun on stage. There were drinks in abundance, and Woody was there with the ever-present ciggie hanging out of his mouth or tucked in the end of his guitar. Ian would be grinning from ear to ear. And they dressed so flamboyantly, too, all silks and satins and flares. I loved ’em. They just had a great time, whereas Free were slightly serious.”

Free bassist Andy Fraser remembers the Faces as “big, big drinkers. We’d be at the same hotel, and Rod especially would be like: ‘Come on, fellas, let’s have a couple of drinks.’ Which essentially meant getting totally plastered. Watching the Faces perform was a bit like a pub singalong on an arena scale. That isn’t to discount Rod’s incredible singing and performing abilities, or the band’s musicianship, which I place very highly. That rough-and-ready, slightly sloppy thing worked very well. You can see from what they’ve all done individually how skilled they are.”

Britain was slow to warm to the Faces. Their earliest gigs, as Jones puts it, were “like pulling teeth”. As with Led Zeppelin before them, it was in America where they were to forge their reputation. In March 1970 the band went over for a 28-date tour. Crowds instantly responded to these raffish incorrigibles who, unlike shoegazing noodlers such as the Grateful Dead or whole legions of denim’n’boogie dullards, were clearly out to have a great time – and take the audience along with them. Plus, as Wood points out: “We were selling them their own music. They understood what we were all about.”

Detroit was where the Faces first got noticed, at a tiny venue in the heart of the city’s black community called the East Town Theatre. It was the beginning of a symbiotic relationship that was to last right through the band’s lifes, even when their popularity was such that they were filling out 17,000-capacity sheds like Cobo Hall. “After The Faces first broke in Detroit,” says Jones, “it just spread like wildfire. By the time we got to the next city, word had already got around. The power of word of mouth was fantastic.”

Their American tours became the stuff of legend. The band would kill the downtime hours between shows by dismantling and defacing hotel rooms, wreaking havoc in the corridors, partying by the pool, plying themselves with freely available supplies of cocaine and booze, and taking full advantage of what seemed like an endless queue of willing groupies.

“America back then was so open,” McLagan explains. “A lot of the guys were either in Vietnam or had gone altogether, so we had all these girls after us. There was no Aids, coke wasn’t addictive – at least that’s what they told us – and here we were. And we weren’t like all the other bands, who dressed in T-shirts and denim. They were wonderful times. The groupies in America were much more forward than the ones back home. In the UK you’d have to ask, in America it’d be a case of: ‘I’ll take you and you. As for you, maybe next time.’

“I remember one morning taking a girl to breakfast, which I never usually did. But we’d had a really great night. There she was, sat across the table from me, when I looked over and realised she had one glass eye. And here I am introducing her to the band. They thought it was hilarious.”

One incredulous British journalist, from Disc & Music Echo, attended an early-hours pool party in South Carolina that spilled over into the adjoining hotel. “The comings and goings from room to room resemble something from a Brian Rix bedroom farce,” he wrote. Such was their escalating reputation that the Faces were soon banned from the entire Holiday Inn chain. They sidestepped it simply by checking in as Fleetwood Mac instead.

Another US tour, billed as a Rock’n’Roll Circus, involved sharing the bill with jugglers, acrobats, Blinko the clown and a Chinese high-wire stripper called Ming Wung. You could argue that it was all somehow in keeping with the Faces’ own high-energy nuttishness, leaping about the stage, swapping mics, whispering in huddles and booting footballs into the crowd. They even designed their own on-stage bar.

“We were the first to do a lot of things,” laughs Jones. “We’d have a white stage, and insist that Chuch Magee, who was our roadie, wore black trousers, a white shirt and a waistcoat, so he looked like a barman. So he’d tend the bar, then quickly do Woody’s guitar and various other things. And we’d have palm trees on stage with us. It was very over-the-top. We took the piss out of ourselves, more than anything.”

It all made for a rambunctious communal atmosphere. Several of the outstanding shots in Faces 1969 to 1975 show the band besieged by stage-crashers, but happily playing on under the watchful eye of the local police. “It was an incredible atmosphere,” confirms McLagan. “The cover of A Nod’s As Good As A Wink… [the shot taken from the lighting rig by Chuch the roadie. Photographer Tom Wright got credit on the sleeve, but he didn’t like heights and asked Chuch Magee to take it for him] captures that pretty well, too. Some people used to follow us from gig to gig in America.” Jones remembers that “it was as if we were in the audience and the audience were on stage. You had the crowd wrapped around you.”

The charitable spirit of bonhomie extended beyond the stage. “In the early days we didn’t have much money,” explains Wood, “so Rod and I used to ponce lifts home from girls in the audience. We’d usually end up with the fat ones wearing glasses, but it didn’t matter. If they had a nice car we’d bundle in and they’d take us home for tea and stuff. And we’d use their phones for long-distance calls because it was so expensive.”

As the Faces’ popularity spread, so did the size and reach of their audiences. They began travelling in private jets and playing enormous venues across the US. Guest musicians started showing up and joining them on stage for impromptu jams. Wood recalls: “In Detroit, which used to be our second home, we were joined by special guests like Tina Turner and Jimmy Ruffin. And I first met Bobby Womack there, then Eddie Kendricks. All these great soul stalwarts, who’d actually come up and sing with us. They were very precious times.”

If Detroit remained their bedrock, then LA was party central, the band entertaining all-comers at the infamous Hyatt House – nicknamed the Riot House, and the scene of all manner of TV-out-the-window madcappery. “Everywhere we went, but especially in LA, we’d have famous film stars and musicians backstage,” says Jones. “It was very glamorous and star-studded. Ryan O’Neal loved the Faces, and every time we played LA he’d take over being my roadie. He’d sit behind me at the gig, handing me towels and drinks. It was surreal.”

Then, of course, there was the music. The first couple of Faces albums – First Step (1970) and Long Player (early ’71) – were patchy and unfocused. They were just as liable to offer up a lovely, reflective ballad like Sweet Lady Mary or classic slop-rocker Three Button Hand Me Down as they were throwaways like Nobody Knows or On The Beach. It wasn’t until A Nod’s As Good As A Wink… To A Blind Horse, released at the fag end of 1971, that the band fully delivered in the studio. The album was quintessential Faces: loud, lairy and stuffed with everything from semi-slapstick romps (Miss Judy’s Farm, That’s All You Need) to wistfully elegiac songs like Ronnie Lane’s Debris – which detailed the hidden scars of his beloved London – and boogified killers like Stay With Me.

Stay With Me became their first UK Top 10 single, in December 1971. By this time Stewart was basking in the solo success of Every Picture Tells A Story and its huge hit, Maggie May. At one point he was simultaneously top of the singles and album charts on both sides of the Atlantic. His follow-up, 1972’s Never A Dull Moment, which included You Wear It Well, consolidated his new superstar status. There were rumours and accusations that Stewart was saving his best songs for himself, further fanned by the fact that his latest album included True Blue, a song cut at a Faces session.

The Faces’ fourth album Ooh La La, issued in April ’73, seemed to compound the question of allegiance. Rod appeared disinterested, failing to show for the first few weeks of recording, leaving Wood to take lead vocals on the title track. In a press interview, Stewart dismissed the album as “a bloody mess”. McLagan called it Ronnie Lane’s record, the latter having written or co-written more than half of it. As a result it was generally more introspective and folksy, though there were still some blustery, laddish rockers like Silicone Grown and Borstal Boys. And of course Cindy Incidentally, which had reached No.2 in February.

“That song came together pretty quickly, which is often how things happen for the best,” recalls McLagan. “I was playing this piano riff and Rod came over and said: ‘What’s that?’ It was actually hung backwards off Memphis, Tennessee, or at least a version of the one Chuck Berry played.”

But the fast lifestyle, incessant touring and increasing friction in the band were beginning to pinch. In May ’73 Ronnie Lane announced he was quitting. It was the beginning of the end.

“It was like a bad joke gone wrong,” remembers Wood, “because we all used to mess about and say: ‘I’m leaving the group!’ It was like a stock saying whenever anything went slightly wrong. Then one day Ronnie actually did come in and say he was leaving. I went: ‘Yeah right, pull the other one.’ But he said: ‘No, I really am. Plus I’m running off with my best friend’s wife.’ This was the wife of Mike McInnerney, who’d done the artwork for our First Step album. So Ronnie ran off with Katie and left Sue Lane, who we all used to love. We’d all say: ‘What are you doing? How can you do this?’ And he’d tell us he was going off to live in a caravan, become a traveller and form his own band. There was nothing more we could say because he’d go: ‘My mind is made up. I’m off.’”

Lane was true to his word, hitting the road with his new band, Slim Chance. The rest were left to weigh up their options.

“Rod summed it up really well,” offers Jones. “He told me that once Ronnie Lane left the band, the spirit of the Faces left too. Ronnie was integral to the band. It was the complete line-up when he was there. It never quite felt the same afterwards.”

They brought in Japanese bassist Tetsu Yamauchi, who’d replaced Andy Fraser in Free, in an attempt to fill the void.

“We made a mistake really with Tetsu,” admits McLagan. “It wasn’t his fault, but he was a party boy and thought he was in for lots of drinks and a little bit of playing, while we were looking for more creation and a lot less boozing.

“But you couldn’t replace Ronnie. Apart from being the originator, he was the glue in the Faces. He was such a sweet person and such a great songwriter. And when he was gone, that songwriting flavour was missing. There was nothing to do then, because Rod wasn’t interested in recording with the Faces, and hadn’t even been interested in doing Ooh La La, actually.”

The band limped on for another 18 months, though all they had to show were a couple of singles (albeit great ones in Pool Hall Richard and You Can Make Me Dance, Sing Or Anything) and a poor, drunkenly mixed live album, Coast To Coast: Overture And Beginners.

In January 1975 Ronnie Wood was offered Mick Taylor’s old job in the Rolling Stones, initially to fill in on tour. “We all said: ‘Yeah, Woody, go ahead, no problem. Just keep it together, because our tour starts immediately after theirs,’” recalls Jones. “But when Ronnie came back he really came back as a Rolling Stone. Rod and I already knew the writing was on the wall, because we’d talked about it. And Rod was moving to America, so you had this great transatlantic divide. There was this huge separation taking place, and Ronnie leaving was the final straw.” By December it was official: the Faces were finished.

Ronnie Lane, who was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in the late 70s, died in June 1997. There have been rumours of a reunion of the surviving Faces, regularly over the years, but it always seemed unlikely, what with Stewart’s comfy solo career, Wood permanently in the Stones, Jones replacing Keith Moon in The Who then forming the Jones Gang with ex-members of Bad Company and Foreigner, and McLagan burying himself in session work and his own Bump Band. There was the odd get-together at the Brit Awards or one of Rod’s Wembley shows, but nothing long-term.

Then, in 2008, Stewart told the press they’d been talking about playing together again. The foursome reconvened for a day’s rehearsal in London, but then everything went ominously quiet. By early the following year, Rod’s spokesman was denying reports of a full-blown Faces reunion; prior touring commitments, it transpired, just wouldn’t allow it.

But the others pressed on. October 2009 saw Wood, McLagan and Jones play a one-off charity show at the Royal Albert Hall, with Mick Hucknall and Bill Wyman in for Stewart and Lane respectively. It was a huge, not to say surprising, success, with the super-lunged Hucknall manfully filling Rod’s heels. An official reunion was finally announced in May 2010, with Sex Pistol Glen Matlock replacing Wyman as full-time bassist.

So far there’s been no recording activity, but the live shows have been little short of spectacular. Hucknall, a Faces fan as a kid, admits it’s been a daunting prospect: “The thing to remember about the Faces, for all the debauchery and fantastic stories, is that they did have a tangible sound. Certain bands have it – Zeppelin had it, the Stones have got it – where you close your eyes and you recognise this energy. And that sound is just unbelievable. So there am I as a fan, in the middle of it, thinking, ‘Fucking hell!’ Along with Mick Jagger and Robert Plant, Rod’s the contender. He’s up there with the greats. I just have to rest on the fact that I’m able to say I’m a fan, the boys are supportive and I’m just blowing it along. I don’t see my position as replacing him. I’m completely willing to stand aside anytime Rod wants to walk out on that stage with them.”

And what of the original Faces? Is there a sense of making up for all that lost time? “It’s a shame we had to split up the way we did,” says Jones. “We should have gone on longer. And that’s part of the reason why we wanted to get back together again – to finish properly. Because the Faces has always felt like unfinished business. And once you’ve had something special like that it’s always nagging away at the back of your head. We’re still great mates, and it’s just nice to play together again.”

McLagan feels the same way. “I’ve waited a long fucking time for this,” he declares. “I’ve been trying for this for years and years. We’ve got gigs lined up, but I’d like more of them. And we don’t know how long we’ve got Ronnie Wood for. The Stones are going to want to pull that string at some point and he’ll be gone. This is our only opportunity.”

It’s a subject that prompts a sudden spasm of nostalgia from McLagan: “I was 24 when I was in the Faces. I was young, I was in love, I had a young son, I was making money, I was playing music with the best band in the world. We were five characters who really got on well. I always laugh when I read about bands having rows and fights with each other – The Who, the Kinks and the rest of them – but we never had that. It was fun or nothing at all. It really was.”

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #162.

For more on the Faces, not least their lavish box set release, then click the link below.