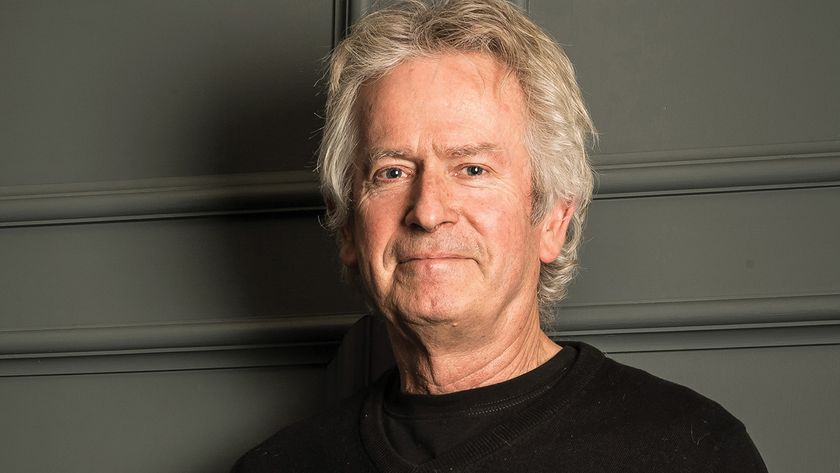

“They were really like a spider’s web, pulling equally in five different directions,” recalls long-time Faith No More producer Matt Wallace. “There was no de facto leader of the band. If any guy tried to be the leader, the other guys would just say: ‘Fuck you’. They would laugh him out of there. They were the most democratic band I’ve ever worked with. No guy could lead that thing. Patton was really into Sade, as was Roddy Bottum. And Roddy was really into the techno thing, and Mike Bordin was into Killing Joke and studied African drumming at UC Berkeley. And Bill Gould was the glue of the whole thing.”

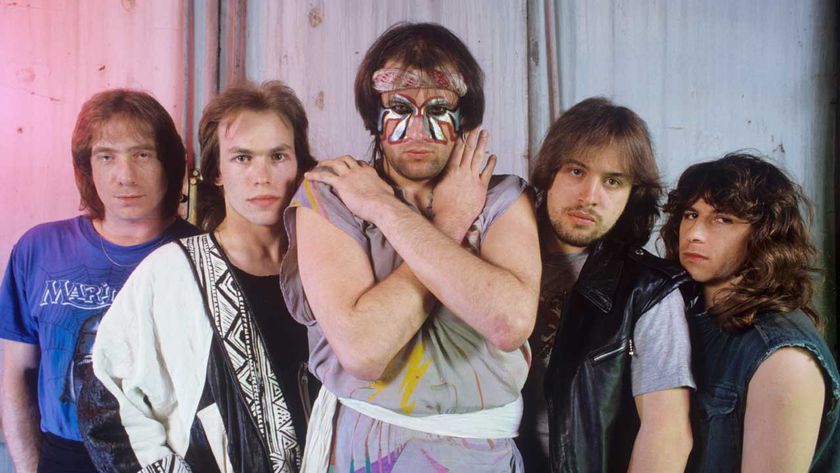

Faith No More rocketed out of the underground and straight up the charts, with a sound soaked in countless styles. And for a period of time in the 1990s, they were one of the top rock bands on the planet. But ultimately, line-up hiccups and bickering would derail them.

The Faith No More story begins with bassist Bill Gould. Coming from Hollywood, he began playing in local bands during the late 70s just as Sunset Strip was being infiltrated with punk groups like The Germs and Black Flag. By the time he had reached 18, Gould had enrolled in college at Berkeley.

“The first thing I did after I unpacked all my stuff in the dorm room,” says Gould, “was walk to the record store on Telegraph Avenue, and look on the bulletin boards to get in a new band. There was a phone number for this guy Mike Morris, who was putting a band together. And that was what became Faith No Man.”

Yes, before Faith No More, there was Faith No Man. Joining Gould and singer/guitarist Morris was keyboardist Wade Worthington and drummer Mike ‘Puffy’ Bordin. But according to Gould, Faith No Man’s sound was far from Faith No More’s.

“It was a little more derivative of what was happening in Great Britain – Theatre Of Hate, Killing Joke, that kind of thing.”

Looking to get their sound down on tape, Bordin recounts that producer Matt Wallace entered the picture the same way Gould did. “[Gould] saw a flyer around Berkeley, saying ‘Dangerous Rhythm Studios – cheap demos, I’ll do anything’. We did some demos with him, and we loved him. A good, fucking fun-loving guy, he was willing to work as hard as he had to.”

Recording soon began in Wallace’s parents’ garage, which led to Faith No Man’ s debut single, 1982’s Song Of Liberty.

“I had pneumonia – a bad bronchial infection, where I couldn’t hear,” remembers Gould. “My ears completely plugged up, so I recorded that record deaf!”

Soon Faith No Man were playing live, but during rehearsals it became apparent that the rest of the members of the band didn’t see eye-to-eye with Morris. Worthington saw the writing on the wall and left, only to be replaced by Roddy Bottum, a roommate of Gould’s. But tensions were growing between Morris and the rest of the band…

“We all just kind of quit,” recalls Bordin. “We said: ‘We’re going to start playing [without Morris]. We like each other, we’ve got a vibe. We’ve got an itch that we want to scratch’. So that’s why there was keyboard, bass and drums, and that’s why we switched guitarists so much, because it was just us three. The ‘Man’ was gone – the man was ‘No More’.”

Now christened Faith No More, the trio began playing out with another guitarist, Mark Bowen, but instead of getting a permanent singer they tried out several. One vocalist that stuck around a while longer than the rest was none other than Courtney Love.

“Courtney was one of the revolving singers we had,” explains Bottum. “She sang with us for probably six months. She was an awesome performer; she liked to sing in her nightgown, adorned with flowers.” But as Gould points out, it just didn’t work out. “She was a very chaotic personality – she took a lot of work. It just got too much after a while.”

With Faith No More having lined up a gig in LA, Gould invited an old friend, Chuck Mosley, to the mic. Gould: “He had a couple of 40-ouncers of beer – I don’t think he’d ever sung before – he just got on the mic and yelled. We had a show in San Francisco after that, and he did it. It just started becoming a band thing.”

Mosley recalls his early days as a singer. “The thing I hear most often is: ‘Did you ever think of going into stand up?’. I learned early on the devastating effect of the in-between song silence with the band trying to talk among themselves and tune up. So I always tried to fill it up by just saying really stupid stuff.”

At the same time, Bowen left the band, and an old friend of Bordin’s, Metallica’s Cliff Burton, suggested Faith No More’s next guitarist. “I was with Billy Gould at a Mexican restaurant in the East Bay, and lo and behold, there’s Cliff,” says Bordin. “He goes: ‘Y’know, you’ve got to get Jim in your band because he’s working a regular job, and it’s fucking killing him. You know he can do what you want him to do’.”

According to Gould however, Martin’s name came with a disclaimer from Bordin, who had previously played with Martin [and Burton] in a band called EZ Street. “Jim and Mike Bordin never really liked each other, apparently. The way it was put to me was through Bordin: ‘There’s this guy Cliff knows. He’s an asshole, he’s always been an asshole. I was in a band with him and I quit because he was such an asshole. But he can play guitar’.”

With Martin’s arrival, the final piece was in place for Faith No More’s musical puzzle, according to Wallace. “I always compare him to the guy who comes in with big army boots and stomps – with muddy shoes – across your floor. He came from a Black Sabbath and Corrosion Of Conformity background. He was really into the much heavier stuff. It was an essential ingredient to weigh the band properly.”

In addition to bringing an added musical weight, Martin was an unmistakable original. “At the time we met, he looked like the star of that movie Eraserhead,” Wallace points out. “He had this slightly tallish, curly head of hair that looked really weird, and he had these really thick glasses. He would just say whatever’s on his mind. It was kind of refreshing to have that.”

Martin remembers these early shows as a time where the group looked towards non-musical areas for inspiration and guidance. “We burned a lot of sage at those early shows and some of the band members liked playing on significant days of the Wicca calendar; such as the summer Solstice or the spring Equinox. These were the really early shows. Once we started in earnest, we left the Paganism behind.”

As a result of the group’s interest in all things Wiccan, Wallace was met with apprehension from a few friends when he went to work with the group on their next set of demos in 1985, which would turn out to be half of their debut album, We Care A Lot.

“Everybody kind of freaked out… A lot of people thought of it as a Satanic thing, but I think they were more into the Wiccan thing. They had this slightly metaphysical thing about them – people were always like: ‘Dude, they’re into Satan!’. But it never phased me, I knew they were creative guys, and that they were going to do what they were going to do.”

With several new songs in the can, Gould handed the tape to a friend that worked at a nearby record store – with specific instructions.

“‘Just play it when people are shopping for records’. It turns out that Ruth Schwartz – who started Mordam Records – was played the tape, and she came up to the desk to ask what music that was. My friend told her: ‘It’s just my roommate’s band’. She asked what label we were on and he said: ‘They’re not signed’. And she called us up two days after that. It’s bizarre, but that’s what happened.” he group returned to the studio to finish off the second half of the record – the entire album being done in “two three-day weekends” according to Wallace. But it was during these sessions that a recurring pattern with Mosley sprung up.

“I probably ‘mental-cased’ myself into a cold, a sore throat, or lost my voice,” the singer remembers. “It just never changed. I was never fully prepared – I was always working on stuff as we were recording. That’s kind of been a trademark of mine – coming to the studio mostly prepared, but not really knowing what I’m going to do on certain parts and having to work them out right there.”

The album was released in 1985, and college radio latched onto the contagious title track.

“I wrote the lyrics to We Care A Lot after listening to a whole lot of Run-DMC,” recalls Bottum. “We didn’t know how damn good it was until we were actually recording it and heard it on two speakers,” admits Gould. “We were surprised that we had this song that seemed to have a life of its own.”

The supporting tour was a whole other story, however. Gould: “We got in a four-door pick-up truck, with a little trailer hitch, and just hit the road. Great fun, great tour, very hard work – had no fucking money whatsoever.”

Martin also recalls the early FNM touring days. “We travelled across the country and had about 30 dates in 90 days. It was brutal. We saw very little money, and as a consequence, we ate very little. Chuck was an asshole. The wheels fell off the truck. We met many generous people who let us stay with them. We lived in the Metroplex in Atlanta, Georgia for a couple of weeks. Rats ate hot and sour soup out of my beard.”

Shortly after returning from their first US tour, work began on their second album [which saw the group jump record label from Mordam to Slash/Reprise]. Released in 1987, Introduce Yourself featured a more focused sound; it also featured a re-recording of We Care A Lot. The album’s ensuing tour saw FNM hook up with another up-and- coming band, the Red Hot Chili Peppers.

“We were travelling in a box van with no windows,” says Martin. Drove all the way to the east coast for the first show. Flea asked me if we liked to smoke weed. I said: ‘Yes’ and he said: ‘We’re going to get along just fine’. We did something like 52 dates in 56 days.”

But it was during the group’s first European shows that it became clear that Mosley was going to be the next to leave the band. The problems were exacerbated when a roadie friend of the singer’s was fired after getting into a fistfight with Martin.

“By the time that happened, Chuck was already kind of out of it for me,” shrugs Gould. “I guess Jim and the roadie had been drinking and they got in a fight. It came a point where Jim was our guitar player, and he broke his hand fighting the guy. It’s the first night of our European tour, and somebody had to go – it obviously wasn’t going to be our guitar player. Chuck took it very personally, sticking up for this roadie.”

On the same tour, tensions ran so high that Gould punched Mosley on stage. The final straw with Mosley happened after the band returned home.

“There was a certain point when I went to rehearsal, and Chuck wanted to do all acoustic guitar songs. It was just so far off the mark – I think I actually attacked him again,” laughs Gould. Instead of simply firing Mosley, the bassist used a tactic similar to the one that had been used to oust Morris several years earlier.

“The upshot was that I got up, walked out and quit the band. Just said: ‘I’m done – I can’t take this any longer. It’s just so ridiculous’. The same day, I talked to Bordin, and he said: ‘Well, I still want to play with you’. Bottum did the same thing. It was another one of these ‘firing somebody without firing them’ scenarios”.

After Mosley’s exit, rumors began circulating about the singer’s alleged party lifestyle. “I’ve never been addicted to heroin,” explains Mosley. “But I’ve done everything from PCP to acid. I had a problem with coke, which I don’t touch anymore.”

Looking back on the split today, Mosley offers his take. “I said: ‘I don’t want to leave, I want to work this out’. I did a couple of things to gesture that I was going to work alongside them, not against them. But by that point, they were already too sick of me. I felt bad about it, but what can you do?” Despite being without a singer, the remaining members of Faith No More set out to write their third album.

“The music was written in shifts on that record, in that that was recorded in LA,” says Bordin. “Jim and I were sharing a place. We were partying hard, and Metallica were in town – people getting fucked up and drinking Jägermeister. That was the beginning of the bad period that Hetfield talked about when he got sober.

“Billy and Roddy were working probably 10am to 3pm. Jim was drinking all night with his buddies – he wouldn’t go to sleep until seven or eight in the morning. We would get up at 4pm and go into the studio around seven, and work until probably 10 or 11pm. So we were totally doing shifts. We didn’t even have each other’s phone numbers. We just went into the rehearsal room and thought we’d see each other eventually. Then one day Billy stayed late or we came early. And then Billy started getting on our own schedule too. We just started writing shit – we were all working on stuff. And ultimately, it all came together. It was very fucking fully realised – ‘This is us, this is what we are’.”

Eventually, the search for a singer began and Soundgarden’s Chris Cornell’s name came up.

“Soundgarden opened up for us a few times in Seattle,” remembers Gould. “We were friends with them. I think one day, Mike and I went to Chris’s house to jam, but I don’t think that we had a musical connection.”

Soon after, it was a then-teenaged singer [who gave Bordin a tape of his band a few years earlier in Eureka, California] that the band began talking about – Mike Patton. Bottum was not exactly wild about the idea.

“Mike Bordin really liked his Mr Bungle tape he gave us,” says Roddy. “So did Jim Martin. I didn’t – not my cup of tea.”

Martin recalls a conversation he had with Patton at this time. “We auditioned about five other people, and it was pretty clear that Patton had superior natural ability,” he recalls. “We called him and told him to come down; we wanted him to go to work immediately. He was very hesitant, like: ‘I can’t do this right now; it’s not a good day. I have a school box social to go to. And tomorrow is show and tell. If I had plenty of advance warning, I might be able to come down for a little while, but today is not good’. I told him he was at a crossroads in life – one way was to become a singer, the other way was to be a record store clerk in a shitty little town in Northern California. He really was like that. Very clean and shiny, nice kid. Milk and cookies type.”

Patton wisely lined up a tryout, and soon became Faith No More’s new singer. With the music already written, Wallace recalls that the group were adamant that Patton work with what he was given.

“Patton was asked to write the lyrics for that record,” says the producer. “And he did that within 12 days – he wrote all the lyrics and melodies. And basically, he said: ‘Hey guys, can I make this part longer or this part shorter?’ And they said: ‘No.’ So the the music was done, and they were taking no input from Patton about arrangements.” In return, Patton was adamant about his singing style.

“He was singing really nasally and also his pitch on record was not as good as I knew it could be,” says Wallace. “I was just like: ‘Why don’t you just hit the notes?’. And he goes: ‘No man, this is my style.’ Because he’d sing the song on tape, and he’d do this amazing, really full voice. I’m like: ‘That’s the voice! Get that on the darnn tape!’. He was like: ‘No man, I don’t want to do it’.

“I never asked Patton this directly, but one of two things happened – one, he was trying to keep that kind of snotty, punky, rap persona, and that was important for him to have that snotty attitude on the recording. Or another possibility was that he still had a lot of loyalties with Mr Bungle, and I think he wanted to separate himself as the singer from Mr Bungle and Faith No More.”

But Patton himself looked upon it from a different perspective, “It was my first record,” he says. “And I was just happy to be there.”

Released in 1989, The Real Thing stuck out like a sore thumb in the hard rock world. Name a style, and it’s probably represented here – rap [Epic], pop [Underwater Love], prog [Woodpecker From Mars], piano jazz [Edge Of The World] and thrash metal [Surprise! You’re Dead!]. America was slow to latch onto the band, but the UK wasted little time – as a sold-out London show was taped in early 1990, and later released as Live At The Brixton Academy. With FNM’s US label deeming The Real Thing ‘dead’ and that it was time to start thinking about the next album, they granted the band one more video – for Epic. A wise move, as it became a huge hit in the summer of 1990, and finally broke the band commercially.

“More than anything, I remember us being in Europe,” says Patton. “And our manager would check in with us maybe once a week. He called and said: ‘Your single is blowing up over here.’ We didn’t believe him. We thought he was buttering us up so he could keep us on the road, and we all wanted to go home. I remember landing in the airport, going to a hotel, turning on the TV by chance and seeing the damn video and going: ‘Oh shit… the joke’s on us!’.”

Staying on the road for nearly two years, the group took most of 91 to write and record songs for the next album. Patton filled his free time with Mr Bungle, while also looking for outside sources for artistic inspiration. “He was into this weird, twisted porn stuff,” says Wallace.

“I remember he was showing me some of these videos he got from Japan. I was like: ‘Dude, what are you watching that for?!’. Crazy shit.” The ‘crazy shit’ was working, and the band continued to make unique music. When the suits at the label heard the material, they heard no Epic II. They weren’t pleased.

“After listening to some of the rough tracks, the president of Slash Records said: ‘I hope nobody bought any houses’,” says Martin. “Of course, some of the band members had, and this comment made them very agitated and anxious. With all the pressure of fame on top of the financial responsibility of home ownership, I began to think this record was too contrived and wanted to take a more freeform approach in the recording process. This was met with great opposition from the new homeowners.”

Wallace also remembers Martin’s dissatisfaction with the material. “He kept referring to the music as ‘gay disco’. He just hated it. And I kept saying: ‘But we really need you – your guitar playing is what’s going to keep it from being gay disco. We need your big army boots in here’. He couldn’t get his head around it, and the band were furious.”

Even with all the tension, Faith No More defied the odds, and released one of the greatest rock records of all time, 1992’s Angel Dust. Unlike The Real Thing, Angel Dust touched upon fewer styles, but it more than made up for it in focus and performance. No other band sounded like Faith No More. But despite this, Angel Dust sold below expectations upon its release in the US [debuting at No.10, but soon falling]. However, it did well in Europe, after a hit single cover of The Commodores’ Easy was added.

When Guns N’ Roses offered the quintet a long stretch of opening stadium dates in the UK and the US, it appeared as though the band had it made. But FNM and GN’R were coming from two completely different worlds.

“There was a rumour that Axl brought his psychic on tour with him,” says Gould. “And it would be bad luck in any city that started with the letter ‘M’. So he cancelled Manchester, Madrid, Munich, and he did Montreal, and that’s when the riot happened.

“It got very bizarre. We saw Axl once or twice the whole time. We did a lot of interviews talking about how it was, and I think the band didn’t appreciate that very much. We got busted one day, and we had to go apologise. It was like getting in the principal’s office. We went and met Axl in his room, and to tell you the truth, he was super-cool and super-gracious. Then some guy comes in, and says: ‘Now that everything’s good, come over here’. We went into some trailer where there’s some lesbian love act going on. It just blew the whole thing. It was so fucking gross that we were just like: ‘Oh God’. We thought we came to some kind of meeting of the minds, and obviously, we hadn’t.”

During this time, Bottum also decided to come out as a gay man. “I don’t know, it happens at different times in all gay people’s lives,” says Roddy. “To the rest of the band I think it might have come out of the blue and was awkward – but only initially. We were all free thinkers, independently motivated and proud of who we are and it’s never been an issue with any of the band members. Including Jim Martin, the guy who you’d typically think would have issues regarding such.”

However, other issues had separated Martin from the rest of the band. “Jim wasn’t stoked on a lot of Angel Dust,” says Bordin. “I think maybe he just wasn’t ready to accept something different, like: ‘Here’s this formula we hit on that works, let’s work on that for a while’. But that’s not how we work. That was never the idea. I mean, think back on Angel Dust and The Real Thing, you can look at those albums as particular sets of music. They weren’t going to be the same – they were never going to be the same. Even the album itself was always incredibly varied – making it a satisfying fucking listening experience.

“But Jim’s contributions, I got to say, between The Real Thing and Angel Dust, dropped off. I mean, I can think of Jizzlobber on Angel Dust, but I can tell you half of fucking Zombie Eaters, a good portion of that whole middle section of Woodpecker From Mars, the whole of Surprise! You’re Dead! He was all over that album, y’know? Those were all parts that he brought, and all of a sudden, those parts weren’t there. It was like: ‘What the fuck is this? What the fuck is that?’.”

Martin, however, casts the blame for tension within the band on two different things. “Patton. He had some weird mind control over Bill and Puffy,” he says simply. “There were many embarrassing displays of megalomania expressed in the music press. Our presentation became very undignified, and as a result, I began to lose interest. Axl Rose and management confronted Bill and Patton for their awkward remarks in the press concerning Axl. Puffy denied association, Bill said it was something else, Patton was excused because he was an idiot. I began to avoid interviews and photo shoots, you know, all the things you need to do when you’re in this business. It was exhausting. The band became more hostile because they didn’t think I was pulling my weight, and they accused me of being one of ‘them’. There was also a dishonest attempt to realign our business agreement. My disinterest deepened. We became estranged.”

The strained relationship between singer and guitarist managed to spill over into the press – on more than one occasion. It was never more evident than in a Melody Maker feature from August 1992, which chronicled the rapidly growing animosity. [“The trouble with modern ,music,” Martin says at one point, “is that there ain’t enough guitar solos anymore.” “I hate guitar solos,” Patton hisses. “Every time our guitarist tries to do one, we stand in front of him.”].

Steffan Chirazi, in his 1994 book, Faith No More: The Real Story, recounted one of the final performances of the Angel Dust tour, at a festival in Belgium: ‘Then, with his back to the stage, Patton hurls a bottle of water over his shoulder towards Martin… It misses by two feet. Had it been a strike, that surely would have been the catalyst necessary to bring this thing boiling over.’

The Martin era officially came to an end in the Autumn of 1993, when the guitarist was fired… via fax. Martin: “I felt relieved; a great pressure had been removed and the pain began to leave my body.” Martin’s replacement turned out to be Patton’s bandmate in Mr Bungle, Trey Spruance. But Spruance recalls that Patton was unconvinced.

“It definitely was not Mike’s idea – he was not really into it. And really, he was right. I didn’t really understand what he meant at the time, but in retrospect, I definitely knew what he meant. They needed a fucking guitar player, and they were having a lot of trouble finding somebody suitable. I mean, their chemistry – it seems to me that the chemistry of that band depended on every band member.”

- The 10 heaviest Faith No More songs

- Chuck Mosley, former singer of Faith No More, dead at 57

- The Story Behind The Song: From Out Of Nowhere by Faith No More

- The 10 best Faith No More songs not written by Faith No More

The resulting album, 1995’s King For A Day… Fool For A Lifetime was FNM’s first-ever recording to not be produced by Matt Wallace, who was replaced by Andy Wallace [no relation].

Spruance: “It was at Bearsville, it was a fucking amazing studio. I thought Andy was in a weird position – he’s being told to make this band sound like a garage band. I’m like: ‘What the fuck?’”

The death of Kurt Cobain was a contributing factor in Bottum entering rehab, to address a heroin addiction. “I was friends with Kurt mostly through Courtney. We became close fast. His death was really a serious blow to me but reinforcing because I’d stopped doing dope myself and it was a reminder of where I could’ve gone with it.”

Just as Martin had been absent on the Angel Dust material, so King… lacked a valued member. “Roddy wasn’t really into the music, so that was difficult,” says Gould. “He was just coming out of rehab, and I guess this is common with people with substance abuse who’ve quit – they re-evaluate all of their relationships, to see what put them there in the first place. And I think he saw us in a very negative light. He wasn’t carrying his weight. We wanted him to – he just wasn’t there.”

King… was another strong album, but it appeared as though the record buying public in the US had forgotten about the band, as it peaked at No.31 [although it made the Top 10 in the UK]. But just a few weeks before the tour was supposed to begin, Spruance left abruptly. Taking his spot for the dates was the group’s keyboard roadie, Dean Menta. Menta recalls band relations during the tour.

“They talked shit behind each other’s backs constantly and avoided each other… pretty much as they always did.”

Faith No More’s shows, however, remained wild, as Patton’s on- stage antics kept Menta on his toes. On one occasion the singer peed into his shoe on stage – and then drank it. Menta remembers “the peeing, the pooing, the drinking the pee, the peeing in the shoe and drinking. The peeing in a cup and handing it to a young girl in the front row who assumed it was water and guzzled it. Things like that.”

Cutting the tour short to focus on their next album, it was agreed among the band that Menta wasn’t a good fit, so a friend of Gould’s, Jon Hudson, became the latest FNM guitarist. Looking back at the recording sessions for the group’s 1997 release, Album Of The Year, Hudson describes the sessions as “fragmented. I don’t know what the other studio experiences were like for Faith No More, I just know that this one was sort of piecemeal. I don’t think it was a lack of creativity, I just think people’s interests were starting to go elsewhere.”

The group held it together long enough to tour in support of Album… which was prefaced by Bordin doing double duty in Ozzy Osbourne’s band. But by the summer of 98, it was clearly over.

“I think it was the right time to turn off the lights before we became a pathetic band,” says Patton. “Creatively, we hit the wall as a band and it was important to some of us that we end it with integrity.”

Despite all the ups and downs, Faith No More’s hard work paid off, as they’re constantly cited as an influence by new bands. Gould: “It is very cool to see even though it didn’t seem to work at the time. If you look at it in the long term, our gut instincts were correct.”

As a result, the question has come up time and time again over the years… could there ever be a Faith No More reunion?

“If I stood to make three million dollars after taxes I would consider it. Really!” smiles Patton. “Why bother unless it is for stupid money? At this point it would not have anything to do with the music. Most of these reunions are sad cash-ins, but to each his own.”

Gould has other ideas. “The only thing that would make me interested in it is maybe to do it in a club in Bakersfield without telling anybody – for 50 bucks.” he says. “Then I would do it. If it was a human thing between human beings, I would do it. If we couldn’t do that, I don’t think there would be any reason. It would be fake.”

And as for how FNM is perceived, Bordin has the last word. “We loved this band. It was our lives. So for people to say: ‘It’s a bad story’ or ‘They didn’t care’ is bullshit. Don’t believe the fucking hype.”

This feature originally appear in Classic Rock 83.