On the evening of September 30, 2014, Royal Blood’s Mike Kerr and Ben Thatcher had their conversation interrupted by a knock on the door of their dressing room in San Francisco’s Nob Hill Masonic Auditorium. Outside stood Metallica drummer Lars Ulrich.

Invited into the room, he introduced himself as a fan of Royal Blood’s debut album, and spoke enthusiastically with the two twenty-somethings from West Sussex about his latest musical discoveries, probing both for further recommendations. He then asked the English pair for their impressions of his adopted home town.

“We haven’t really had the chance to see much of it,” admitted Kerr.

“Let’s change that,” said Ulrich, holding up his car keys. “Let’s go.”

As Ulrich’s car sped across the Golden Gate Bridge, Kerr and Thatcher sank back into the leather upholstery and exchanged disbelieving smiles. By any given standard, 2014 was proving to be a most remarkable year.

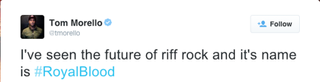

“I’ve seen the future of riff rock and its name is #RoyalBlood.” Rage Against The Machine guitarist Tom Morello’s tweet after seeing Royal Blood play Los Angeles’ storied Troubadour club in September may have carried a knowing echo of music critic Jon Landau’s famous assessment of a young Bruce Springsteen, but its tone was entirely consistent with the hype and excitement that has accompanied the Brighton’s duo’s vertiginous rise over the past 12 months.

This, unquestionably, is the most talked-about band of the year. To date, Royal Blood’s self-titled debut album has sold 155,000 copies in the UK, 66,000 of those in its first week on sale in August – a statistic which not only secured the record the top spot on the national album chart, but also ensured that Royal Blood became the fastest-selling rock debut in the past three years.

Their performances at Download, Glastonbury, T In The Park and the Reading and Leeds festivals this summer drew huge crowds to small tents, they’ve been fêted by Jimmy Page (who showed up to a New York show in May) and had their debut album nominated for the Mercury Music Prize. A 14-date tour of Britain and Ireland scheduled for next February/March, taking in venues such as London’s 4,800-capacity Brixton Academy, Blackpool’s Empress Ballroom(3,000) and a two-night stand at Glasgow’s Barrowland sold out within minutes of tickets going on sale in October. As if all this weren’t dizzying enough, mainstream media outlets have now taken to labelling the duo the new Saviours Of Rock.

There are audible sighs from Kerr (bass, vocals and beard) and Ben Thatcher (drums and even bigger beard) when that tag is brought up in front of them. Sipping coffee in the corner of a Tyneside bar ahead of the opening night of their latest sell-out UK tour, the pair may be sufficiently well known that a couple of blushing female fans will sidle over for selfies and hugs, but in their black hoodies and sensible winter jackets, they resemble engineering students more than rock gods, and their conversational tone is unfailingly polite and low-key to the point of self-deprecation. Open enough to confess that a dinner of seared tuna in Dublin the previous evening brought on a worryingly intense dose of pre-gig diarrhoea for both of them, they exhibit a certain guarded wariness when the red light on the tape recorder placed on the table between them is illuminated.

“We’re not interested in selling ourselves, we’re interested in playing music,” Kerr says at one point. “We’ve never sold this band on personality.”

Nevertheless, their thoughtful, reasoned outlook on the tumult which has enveloped them offers an interesting snapshot of the mechanics and machinery of modern fame.

“There’s nothing we can do to control what the press write,” says Kerr. “That ‘Saviours Of Rock’ tag is a dramatised headline, but it doesn’t really make any sense. When was the last time you heard an artist called the Saviour Of Jazz? Jazz hasn’t gone away, and neither has rock’n’roll. To say rock’n’roll is dead is just mental. It’s impossible for something as important as that to die. We feel no responsibility to save anything. How could two people take on the responsibility for an entire genre? That’d be insane pressure. Fuck that. This is about our music, nothing else.”

As with most ‘overnight success’ stories, Royal Blood’s roots extend deeper than one might imagine. Both raised in families of five children, Kerr and Thatcher have known each other for the best part of a decade, and have been playing together in unheralded bands since their mid-teens, “when you don’t know what you want to do or who you are”, says Kerr. The elder of the two by a couple of years, Thatcher received his first full-size drum kit at the age of six. By the same age, Kerr was beginning piano lessons.

Brushing aside queries about their early inspirations with the simple rejoinder: “If you love food, sooner or later you’ll start wondering how it’s made, and you’ll want to learn to cook,” Kerr will admit that both of them grew up on “the same bands that everyone else loves – The Beatles, The Beach Boys, Queen, Zeppelin, Sabbath, Queens Of The Stone Age”, noting: “We were so obsessed with music that we were destined to pick up some instrument and join in. It’s a natural curiosity.” Growing up in the sleepy seaside towns of Worthing (Kerr) and Rustington (Thatcher), it was perhaps inevitable that their paths would cross on the South-East music scene.

“We used to play together in a wedding band, playing Lionel Richie and Michael Jackson covers,” Thatcher says with a laugh. “We’d learn songs whether we liked them or not, just because we had to. That’s the best kind of musical education, and a good way to understand how music works.”

In 2012, Kerr took a break from music to go travelling in Australia. When he returned to England, Thatcher collected him from Gatwick airport and the pair plotted their next musical collaboration on the journey to Brighton: a stripped-down rock band with Kerr on bass and Thatcher on drums. Within 24 hours they’d written four songs and played their first show, at an open-mic night at the Tangerine Bar in Worthing.

“I’d been away so long that I wanted to hit the ground running,” Kerr says simply. “We’d just missed having fun and writing music together. We’d had so much practice writing songs and we were quite proud of them so we just wanted to play them to people. “

“We didn’t have a mission statement as such, but we definitely knew what we didn’t want to be,” he recalls. “We wanted everything we were making or doing to come purely from our chemistry. We wanted to see if we could make an entire record with just bass, drums and vocals, without adding anything. It’s good to have a blueprint, because a recording studio can be a very tempting, luxurious place, with all the different instruments and effects. If you’re not careful you can come out with something that’s a really warped version of your original vision.”

Asked how quickly he felt Royal Blood were on to something with their new sound, Kerr responds in a heartbeat. “Immediately,” he states. “And by ‘on to something’ here I just mean that we knew it was fun. I don’t think we realised that we had any commercial value to what we were doing. It wasn’t like, ‘We’re going to make it!’ It was just obvious that this was the most fun band we’d been in. We couldn’t believe how simple everything was. But we didn’t have any sense of it going anywhere.”

In truth, there’s no great mystery as to what draws an audience to Royal Blood. A Venn diagram of the band’s core influences would take in Zeppelin, Sabbath, Muse, Queens Of The Stone Age, Nirvana, The White Stripes and Rage Against The Machine – some of the most commercially successful and best-loved rock bands of all time. Royal Blood’s art has been to distil four decades of rock’n’roll history down to its core components – huge riffs, hooky vocals and heart-stopping dynamics. Their songs could scarcely be more perfectly formed if they’d been created via a GarageBand computer algorithm. Still, such gifts are no guarantee of success, and the duo undoubtedly owe a debt to some of the music industry’s most powerful tastemakers when measuring their ascent.

In December 2013, less than a year after their formation and just two weeks after the release of their debut single Out Of The Black, Royal Blood were placed upon the BBC’s influential Sound Of 2014 list, a showcase of new talent – compiled by DJs, bloggers, music critics and industry ‘players’ – expected to break through into the mainstream in the coming year. That Royal Blood were the only rock band on the list immediately drew media attention: on the day the longlist was published, the Independent newspaper hailed the Brighton “power duo” as “the last hope for rock music”, a spectacularly inflated piece of hype which nonetheless put the band firmly in the spotlight. Such pressure might have damaged less confident collectives, but as Kerr recalls, the accolade barely registered on Royal Blood’s consciousness.

“In all honesty we hadn’t even heard of that list when we were first told we’d been included,” he confesses. “When we looked into it we were like, ‘Oh, yeah, that thing.’ And I guess it was then that we got the significance of it, as there’d been some big artists on that list in the past. But we didn’t really feel like that added any pressure. It was just a nice little opportunity for us to introduce ourselves to the British public. We’d have been doing what we do whatever.”

There is, of course, a certain self-fulfilling prophesy to such industry-compiled lists. Two names on the Sounds Of 2014 list had already sung on No.1 singles before the list was published. And having tipped these artists for greatness, the BBC would obviously have something of a vested interest in propelling said artists into the spotlight.

By the spring of 2014, after Royal Blood had proved their potential with a series of stunning live shows at the annual South By SouthWest (film, interactive and music festivals and industry conferences) in Austin, Texas, they were already a priority act, playlisted on Radio 1, with Head of Music George Ergatoudis praising the band’s “power, energy and brand value”. “They’re exciting and different and they’ll cut through,” he predicted, as the BBC lined up live TV/radio coverage of the band’s scheduled appearances at Radio 1’s Big Weekend in May, Glastonbury in June and T In The Park in July. Each gig subsequently proved to be another milestone for Royal Blood, who were fast gaining a reputation as the ‘must see’ band of 2014.

“With things moving at the speed they’ve been moving at, it can be difficult to gauge where you’re at,” says Kerr. “Moments like that were the opportunities where we’d look at each other and go: ‘Fuck, this is happening.’ You’re too in the moment to appreciate it at the time, but a few days later you’ll wake up and go: ‘Fuck, that was mental.’”

“I still don’t think I’ve woken up,” Thatcher says with a laugh. “Because everything has happened with such speed, we really haven’t had time to process things. To some extent the whole thing is like an out-of-body experience, like we’re watching it happen to someone else. I’m sure some bands who’ve been slaving away for years might resent our rise, but it’s almost as if it’s not under our control.”

Asked how far this fast-moving band are looking ahead, Kerr replies immediately: “Tomorrow.”

“If you ask Mike where we’re going to be playing for the next couple of days, I guarantee you he won’t know,” Thatcher says, laughing.

“There’s no point,” says Kerr. “My brain is focused on tonight, on what I have to do tonight to make sure tonight is brilliant. And then later I’ll worry about how I’m going to get to sleep. And then I’ll worry about how to tackle the next day. We’re so busy that to try to look ahead and prepare ourselves mentally for the next month would be stupid. We’d lose our minds.”

It’s no exaggeration to say that Royal Blood could have sold out Newcastle’s 600-capacity Riverside, where they open their UK tour, for a whole week. The band were asked to upgrade the tour into larger venues but refused. “I don’t believe in making some short-term statement about our stature based on venue sizes,” he says. “We’re in this for the long-term. There’s no rush.”

That said, the crush inside the club this evening verges on dangerous, with bouncers rushing to close off sections of the multi-room venue as temperatures rise and tempers flare.

Perhaps in a bid to lower the mercury levels, Kerr and Thatcher begin their set not with one of the bigger hitters from their album, but with Hole, from their debut EP. It doesn’t matter: the audience explodes with delight regardless, singing along to the central riff from its opening bars. And it’s instantly evident here what a terrific, taut live band Royal Blood are. There’s no superfluous fat on the bones, little that’s grandiloquent or fussy. As with Muse in the past, one is tempted to scour the stage for additional band members, such is the air-shifting force of Figure It Out, Ten Tonne Skeleton and Little Monster. Really, two-piece bands simply shouldn’t sound this huge.

It’s all over in just 55 minutes, with no encore, but there are no audible complaints from a drained audience, only broad smiles and excited chatter.

Upstairs, in a dressing room area that redefines the word ‘spartan’, Kerr and Thatcher seem satisfied with the gig, their one complaint being that one overzealous fan made off with one of Thatcher’s trainers after the drummer ended the night with an exuberant stage dive.

“You know, you can hear ‘Jimmy Page is at the show’, or ‘Tom Morello is at the show’,” Thatcher says, “but every night there’s five hundred other people who’ve come to see you, and who’ve actually bought tickets, and that’s who you’re putting the show on for. This is why we do this.”

“Beyond all the hype – and I hate that word – most of our best moments come on stage,” adds Kerr. “One of the most inspiring things I hear is when we meet mums or dads who’ve brought their kids along to shows and they talk to us and say: ‘They’ve been listening to all this terrible music, but now they want to know who Led Zeppelin are.’ Never mind ‘saving’ rock, if we’re some kid’s first rock band, that’s pretty cool.”