Leeds, October 25, 1989. It’s a cold, wet night, slate grey skies are overhead and won’t shift. It’s not an evening to be out. Inside the Duchess of York, it’s not much better. Out front, there’s a sparse crowd – the place holds 200 on a good night, and tonight is not a good night. Backstage, three days into their first UK tour, things don’t appear to be much better.

There, the seven members of Tad and Nirvana – Tad singer Tad Doyle, guitarist Guy Thorstensen, bassist Kurt Danielson, drummer Steve Wied and Nirvana singer Kurt Cobain (then Kurdt), bassist Krist Novoselic and drummer Chad Channing – are half asleep as showtime looms. They’re wrapped in blankets and huddled around a small electric fire, trying to keep warm, trying to keep the blood moving. But, despite it all, each of them has half a smile on their face.

Anton Brookes, then the UK publicist for the Sub Pop label to which Tad and Nirvana were signed, remembers the scene. And though he also remembers the coldness and the greyness outside, what he retains the most about the seven people huddled in that dressing room is one thing: “camaraderie”. Just over a month later, Nirvana would become the underground’s hottest band – but it would take a gruelling tour, a breakdown, and a suicide threat to get them there…

The Heavier Than Heaven tour started in Newcastle on October 23, 1989, to little hype. It culminated in a show, Lame Fest, at London’s now demolished Astoria, that would be the making of Nirvana.

It was a tour on which Tad and Nirvana would rotate the headline the slot. Most fans, though, were there to see Tad despite the fact Nirvana’s debut Bleach had been released four months previously. Magazines like NME and Melody Maker were not interested, more concerned with the shoe-gazing sounds of Ride or My Bloody Valentine, while the Madchester baggy scene was of more immediate relevance than an alternative act from the unfashionable North West states. Only Sounds magazine were treating the Sub Pop bands to any degree of seriousness while on Radio 1 the DJ John Peel was a key early champion – but, then again, he championed a lot.

That October, Tad and Nirvana were by no means a draw. The first night in Newcastle – tickets £4 in advance, £4.50 on the door – Novoselic was hit by a beer bottle thrown from the crowd and rammed his bass straight through his amps in response. But slowly a slight buzz – helped by Sounds and Peel – had spread, a subterranean hum that there was something about this pair of bands signed to the hip Sub Pop label. Most of the appeal centred on Tad Doyle, Tad’s charismatic front man. Even the promoter who booked the shows, Russell Warby, remembered that Doyle was “this huge guy in a straw hat” when he picked him up from the airport. Cobain, however, was “this funny little fella with bleached hair.”

Nirvana had very little touring under their belts at that stage. They had only been a band for two years and had flitted between being a three-piece and a four-piece – just recently they had settled again on being a trio after letting guitarist Jason Everman go. Their performances were understandably inconsistent as a result and, though occasionally thrilling, they rarely delivered the tightness they would find once drummer Dave Grohl was added to the ranks.

Though the second date of the show, at Manchester Polytechnic, was wilder and looser than in Newcastle, it wasn’t until Leeds that they were on an upswing. First on that night, Nirvana marched out of their cold dressing room and onto the stage. And as Brookes says, “they slayed.”

The publicist was stood at the side of the stage watching and, as Novoselic walked off at the end of the set, Brookes said something flippant – he thinks, perhaps in reference to Newcastle, that it might have been something like: “Krist, you didn’t throw your bass”. At which point Novoselic just shrugged and then …

“… He just hurled his bass behind him without looking,” says Brookes. “His bass went flying across the full length of the pit and everyone’s head snapped back as this massive bass came flying past them. It was still plugged in! I went ‘Why did you do that?’ He offered some explanation but I can’t remember it – but that was the sort of exciting show they were putting on.”

Brookes a natural and instant affinity to Nirvana and their Sub Pop contemporaries. Not someone who could entirely associate with the then prevailing sounds of heavy music – the fag end of hair metal, the British indie shoegaze scene – he found that he could relate to the disaffected teenagers of backwoods America. He would not be the only one, but he was one of the first.

“It felt like something was happening with Mudhoney, Soundgarden, Dinosaur Jr, Screaming Trees, Jane’s Addiction,” he says. “This new wave of bands was coming over, courtesy of John Peel, and it was really exciting. It was fresh new music being made by kids who looked like us. The bands were from the arse end of America and we were from the arse end of the UK and it was exciting.”

He struggled to convince the national press though. “In the UK, the Sub Pop sound was up against Madchester, Baggy and shoegazing and so coverage was quite sparse,” he says. “I would phone people up about Nirvana and they thought I was talking about a band called Nevada. It was difficult.”

But the bands themselves loved him for trying. “Nirvana and Tad were lovely people, like all the Sub Pop people and bands. They were nice, polite, funny, courteous, insightful and witty. They were everyday, normal people – they just happened to be in bands.

“In terms of Nirvana, Kris was more the ambassador of the band and was more outspoken, while Kurt kept himself to himself. But if you got Kurt on a one-to-one level, and he was the perfect host – funny, amusing. Sometimes, though, he could be withdrawn. You knew there was something different about him. He was shyer but still friendly and inquisitive about your life. He’d want to know things about you. All three of them would always thank you for your efforts and would let you know how much it meant to them.”

Both Tad and Nirvana were travelling together that October in one small, shared van. They stayed occasionally in shared rooms in bed and breakfasts, but for the rest of the time they were in each other’s faces permanently. It would be the same van in which they would travel across Europe on a tour that crammed 37 shows into 42 days. “Everyone was stuck in a van, sleeping on floors and they had minimal money,” says Brookes. Slowly it would begin to get to Cobain.

But first was a BBC session for John Peel (Love Buzz, About A Girl, Polly and Spank Thru) and then a performance that half of London claims to have been at, but in reality was attended only by those in the know.

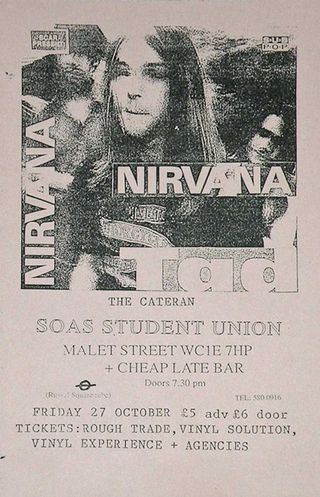

The Nirvana/Tad show at the School of Oriental and African Studies – SOAS – on October 27, 1989 was one that was marked by high spirits – from both crowd and band. Nirvana were on first again and were good, if not spectacular, as crowd surfers bombed past them off the stage.

“They were tight and it was a consistent show,” says the music journalist Keith Cameron, who was there and who had championed the Sub Pop bands in Sounds magazine. “But it didn’t have the peaks that would subsequently come. It was a great night though.

“I was lucky to see the SOAS show because Anton Brookes had organised for me to go out to see Mudhoney in the States. Anton, bless him, had got the dates wrong. He sent me out to Heathrow a day early and, when I tried to check in, the people on the desk told me to come back the next day. So I phoned Anton and he said, ‘Well, at least you come and see Nirvana tonight’. I was actually quite grateful to him.”

Cameron says: “Nirvana were finding their feet at that stage, definitely. Kurt was still honing what he wanted to do as a songwriter and, live, they just weren’t a consistent proposition – some nights they could be amazing and some nights they were just alright. At SOAS they were pretty good. I seem to remember that I spent much of my night stage-diving.”

At the end of the set, Cobain wanted to ramp things up and turned to Brookes. “Why don’t you let off a fire extinguishers,” said the publicist, and so he did. But though Nirvana would remember the show as their favourite of the initial UK run, it was Tad who were the better band that night.

“I honestly thought Tad were better,” says Cameron. “They were tighter, they performed well and they had an obvious star frontman. Kurt’s star qualities were of a different stripe.”

Within two years, of course, Nirvana’s second album Nevermind would make them the most talked about band in the world. Tad, however, remained revered but obscure. Not that anyone could have predicted that at SOAS.

“I didn’t come away from the night thinking Nirvana were going to be huge,” says Cameron. “Nobody – not even a year later when Dave [Grohl] was in the band and I was telling everyone that they were going to be huge – had any idea what huge would actually mean. Nobody could have known what would happen.”

Brookes agrees: “With a good second album, I thought they might be able to headline Brixton Academy and maybe even sell it out,” he says. “Who knew?”

November was spent in Europe and, in Cobain’s case, in increasing misery. He slowly grew homesick and tired of the van. Naturally shy, he was being forced to share his personal space with both his band and Tad and it began to get to him.

“Kurt was missing his girlfriend Tracy [Marander] quite a bit,” says the Sub Pop co-founder Bruce Pavitt, who joined the tour at the end of the European leg. “To a guy from a small town like Aberdeen, Europe was exotic and interesting but after a while you miss the food at home. Then it becomes an alien experience that wears you down – especially if you’re an introvert like Cobain was. Despite his ability to go onstage and rock, he was essentially a quiet, hermit-like introvert who was particular about the food he ate and the people he hung out with.”

Nirvana and Tad played Berlin the night after the Wall came down. They played Austria, Budapest, Switzerland. They got kicked out of a hotel in Amsterdam thanks to a drunken Novoselic. They played everywhere. By the time the tour reached Rome, Cobain was at the end of his tether, threatening to leave the band and telling people he was going to throw himself from the balcony of their hotel. Pavitt says it was a full-on breakdown.

“Touring can seem glamorous from the outside but on that level it can be brutal,” says Pavitt. “Night after night, they were living in a small van. Watching Cobain have a nervous breakdown in Rome was a hard thing to watch. We were a family operation so everybody we were working with was a friend. Seeing my friend that worn out was hard to see.”

The performance at the Piper Club in Rome on November 27 was antagonistic. Tad went on first and bassist Danielson fell into the crowd, yelling “Fuck the Pope” just four miles across the Tiber from Vatican City. Ten songs into Nirvana’s set Cobain – furious at the sound – smashed his guitar into matchsticks and hazardously climbed a speaker stack. The crowd told him to jump and Pavitt was genuinely concerned that, given his state of mind, Cobain just might. “If he had,” he says, “he would have broken his neck.”

The following day, Cobain would get his wallet stolen to further blacken his mood. But then, five days after that, everything would change. Nirvana would play the most important show of their lives.

To the Sub Pop founders Pavitt and Jonathan Poneman, the show they were putting on at The Astoria on December 3 was huge. Their hottest act, Mudhoney, were playing with two of their most exciting – Tad and Nirvana. And they were doing it in front of the British media – who had, by then, caught onto Sub Pop’s potential. “That was our biggest press opportunity ever since we had Mudhoney and Nirvana playing in front of the entire British press,” recalls Pavitt.

Cameron remembers that Pavitt and Poneman were sharp operators. “They certainly weren’t just another American indie label putting out records,” he says. “There was something about them. Jonathan and Bruce were very media-savvy in a way that you weren’t used to seeing from American indie labels at that point. They were very attuned to the influence the British music press had in those days – and as somebody who worked for the British music press, this made a very pleasant change!

“Jonathan and Bruce were coming from the huckster school of promotion and it reminded people in the British press of Malcolm McLaren and Alan McGee. It made for good copy. And what was key was the fact they weren’t selling rubbish – the bands were great. Yes, there was a little topspin, but the bottom line was that most of the bands were incredible.”

It was as if everything had come together perfectly for that night on the Charing Cross Road. The press were tuning into Pavitt and Poneman’s soundbites, Sub Pop had three of their best bands in the same place at the same time and had caught the media’s attention. Meanwhile Mudhoney were going from strength to strength, while Nirvana and Tad were relieved to be at the end of a gruelling tour and Cobain in particular was determined to end a difficult personal period on a high. And, tough though it was, the European tour had sharpened Nirvana up into a much more ferocious live proposition.

“Prior to that European tour, they were seen as an opening act with a few good tunes,” says Pavitt. “After touring night after night for six weeks, they had really fine-tuned their show. Cobain’s songwriting was just coming into a deeper level of maturity and their show began to come into its own. So by the time they reached London, they were ready.”

Nirvana and Tad arrived disastrously late: a missed ferry had delayed their journey from mainland Europe. Nirvana then lost the coin toss and were forced to go on first: no soundcheck, no food, no rest between unloading their gear and getting onstage. Brookes says they were happy about that as it gave them the rest of the night off; Cameron says that they weren’t. Either way, the fact that they were opening the gig fired Cobain up. He was insistent that they were going to steal the show.

But technically, what happened next was a disaster. “Hello, we’re one of the three official representatives of the Seattle Sub Pop scene from Washington State!” yelled Cobain at the start of the set. Within a minute of opener School, he had broken a string on a new guitar purchased after he smashed his in Italy. And he kept on breaking them. String after string, the set bedevilled by technical issues. To a good number in that room, Nirvana’s set was diabolical. “My recollection was that Nirvana was fucking shitty,” says Mudhoney drummer Dan Peters. “They could barely get through a song, let alone 10 songs.”

Novoselic was whirling his bass over his head and nearly hit Peters with it, further angering him. But slowly Peters began to feel for them as yet another string twanged off Cobain’s guitar. “I was sitting there going ‘this sucks’,” says Peters. “I wasn’t saying that they sucked, but I was saying, ‘This sucks that this is the big London show and this is happening’.”

He was one of the few though. “The Lame Fest show made my jaw drop,” says Cameron. “It was a show that was full of problems for them. They were clearly unhappy, their equipment was breaking down but their performance was thrilling. How they dealt with those tensions and problems onstage was electrifying really.

“Lamefest was the moment I thought, ‘Wow, there’s something truly special about this band.’ Not everything went right for them but they found a way to navigate through it. They thrived on the tension. They walked the precipice and won.”

There was a constant wave of stage divers – at one point in the show, Sub Pop employees, other bands, Brookes, Cameron and half the journalists in the room all did a co-ordinated stage dive – and there was something about the air of chaos and end of tour anarchy that fed into a wild, but thrilling performance. When the reviews came out a week later, it was as though Mudhoney and Tad hadn’t even been on the bill. “After that gig,” says Brookes of the press reaction, “everyone was saying ‘Oh my God’.”

Cameron went backstage to talk to Cobain afterwards. He was happy and peaceful, glad to be heading home. And it was then that Cobain made the sort of statement that people in bands often make in the adrenaline high that follows a good show. It’s just that in this case, he was proved to be emphatically right.

“He was in a very good frame of mind,” says Cameron. “He was happy and chatty. It was the end of the ‘80s and I had to do a little questionnaire about the decade gone and what his hopes were for the ‘90s. He said he wanted “to debase every known form of pop music”. Of course, that turned out to be a very accurate prediction…”

It's been decades since Nirvana grabbed that triumph from potential disaster. And it was the show and subsequent press hype in the UK that propelled them to worldwide underground attention. It would take the second album, Nevermind, to push them into the overground (and the arrival of Grohl) but after Lame Fest everything changed.

“London was a tipping point for them,” says Pavitt. “After that, they toured the West Coast [of the USA] with Mudhoney in early ’90 and that was when people really started to notice Nirvana. That’s when they started blowing people away.

“I remember [Mudhoney guitarist] Steve Turner calling me up and saying, ‘Last night Kurt Cobain played guitar standing on his head’. I said, ‘No, no, that doesn’t make any sense’. Then I saw a photo Charles Peterson took. That’s the level of self-expression that was happening by February 1990 and it all happened because they had to prove themselves over and over again in Europe. It was trial by fire.”

Brookes felt the same. He thought that the Heavier Than Heaven tour was the making of them: “It just had something. Whether it was going to translate into ticket or album sales or, from my perspective, more media coverage… well, who knew? But from a fan perspective it was brilliant. After being a part of it, seeing them play, helping to load the van, having a drink with them and being backstage, you wanted them to be bigger because you believed in them. After Lame Fest, it was obvious that Nirvana were the band on Sub Pop.”

Bruce Pavitt’s The Subterranean Pop Music Anthology was published in 2014.