The limo is revving up several storeys below Adam Duritz’s elegant London hotel suite, to take him to a radio interview that just can’t wait, one which made the PR pull the plug on Classic Rock’s time 20 minutes ago. But Counting Crows’ singer gestures for the tape recorder to be turned back on. He’s just been asked if his band, one of the biggest in the world 20 years ago when their song Mr Jones owned the airwaves, but critically dismissed, even derided since, get the respect they deserve.

“Oh, I don’t know,” he begins with deceptive calm. “Nobody deserves anything. This is just the way the world works. There’s a lot of assholes around, and they’re going to use you. And look, I love reading [gonzo rock critic] Lester Bangs, and he loved music. Unfortunately, people didn’t learn to love music and write about it from reading Lester Bangs. They learned how funny and cool it is to shit on James Taylor. I’m not the hugest James Taylor fan myself, but some breakthroughs teach everyone after them shitty things – The Police are awesome, reggae-rock, not so much. I love Miles Davis’s Bitches Brew – fusion, hmmm….

“With Lester Bangs, the main thing critics derived is venom,” he continues. “And what I know is that I love every one of our records. They’re exactly what we wanted them to be at that moment. It’s not everybody else’s responsibility to love that. Do we get the respect we deserve? I don’t know what we fucking deserve. I think there are always going to be bands that are critical darlings, who get blowjobs no matter what they do, and they deserve it. But that isn’t going to be us. I don’t know if that means we deserve anything different, though. That’s just how it worked out.”

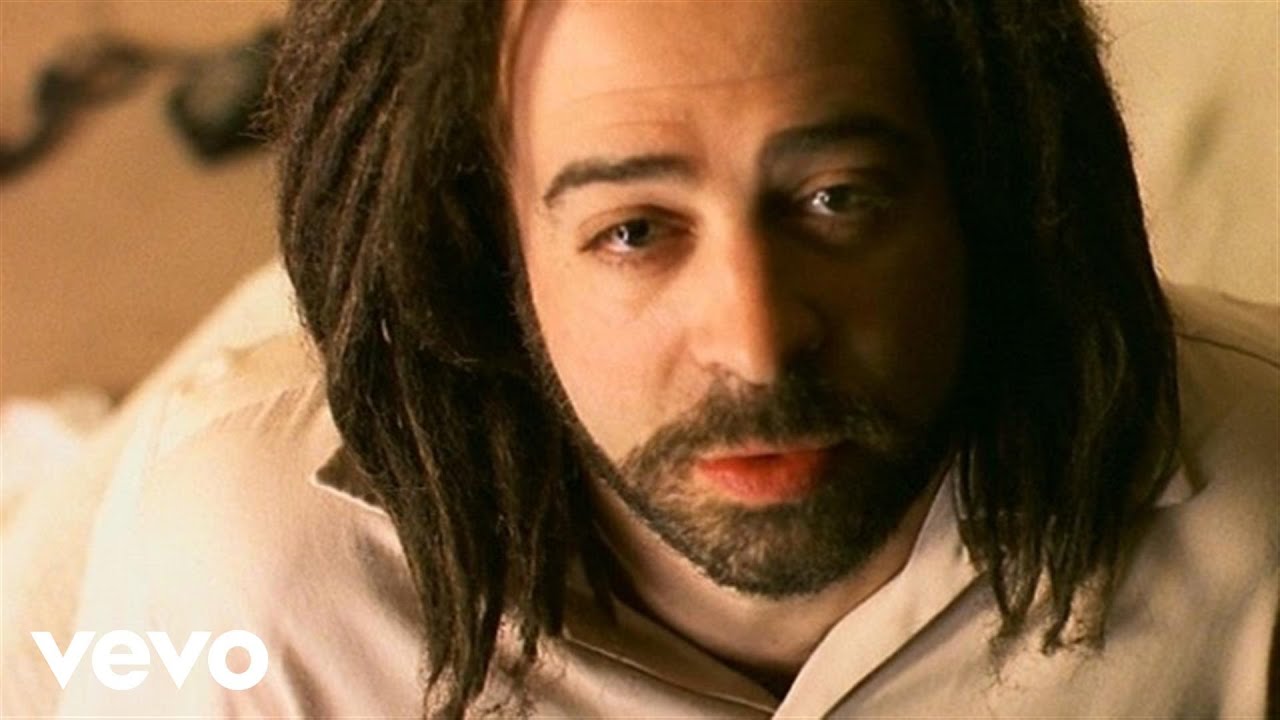

Counting Crows were never really hip. In 1993, as their debut album August And Everything After stormed towards 10 million sales, they sounded like the rootsier, soft end of grunge. Influenced by The Band, Van Morrison and REM more than punk, and made approachable by folksy mandolins, soulful organs and Duritz’s warm voice, Counting Crows’ music was ubiquitous on MTV and in student bedrooms. Duritz’s troubles were as genuine as Kurt Cobain’s, and just as relentlessly mined for lyrics. He adopted his distinctive, matted dreadlocks before he was famous because he was “disappointed when I looked in a mirror before”. But when this strong image was combined with a propensity to date half of 90s Hollywood, including two-thirds of Friends’ female cast – Jennifer Aniston, briefly, and Courteney Cox – he became a figure of fun for some. As he continued to wrestle with his failed relationships and strained mental state over five subsequent Counting Crows albums, diminishing creative and commercial returns set in. For many, in Britain especially, Counting Crows have slipped into the ‘Where Are They Now?’ file.

Today, beneath his dreads Adam Duritz at 50 resembles Robert Downey Jr to a distracting extent. Hardly pausing for breath, he considers his band’s relationship with the industry they briefly ruled. “I started off my career playing at the Rock And Roll Hall of Fame as an unknown band,” he remembers. “I don’t know that I would even show up if we got into it now. That stuff seems like such bullshit to me, the approval of all those people who were just dicks in high school, the same as I was. Rock’n’roll’s cool from the bottom up, so you get cool by exposing people to music they haven’t heard before. We can’t wait to shove the latest indie band we’ve found down people’s throats. All music geeks are that way. So once you’re huge, it’s not as cool. It would be great if everybody loved you all the time, then you could be popular like you wanted to be in high school, and like I wanted to be when I wrote Mr. Jones, but I knew wasn’t going to happen.

“The truth is, they want you to be cool and indie,” he explains, “but they also want you to go to the Grammys. I have never gone to the Grammys, because I don’t give a fuck about the Grammys or the MTV Awards. They’re boring, and I really don’t want to be bored. What I care about is making records and playing shows, and my friends who play music. And you just can’t get everyone to love you. Look at what happened to U2 with their new record. Those guys have always been really obsessed with being relevant, and ahead of things. But you can’t always be. And after a while, does it really matter? U2 got about as big as you could possibly be while still being cool, around Zoo TV time. But somebody out there still thinks they’re a joke. Whether everyone thinks you’re the greatest thing in the world or not, you don’t get to stay there. Eventually, everyone’s ridiculing you for some other reason.”

It’s time, though, for the ridiculing of Counting Crows to stop. Their first new songs in six years, on their seventh album, Somewhere Under Wonderland, are a completely unexpected exceeding of all their previous form. Not coincidentally, they rip up Duritz’s songwriting rulebook, replacing self-analysis with exhilarating storytelling, overdriven guitars and fictional characters. It’s a head-spinning road trip through, with Duritz temporarily forgetting his troubles to enjoy the ride, and enrich his lyrics with pop-culture Americana, from Warhol muse Edie Sedgwick to Big Star singer Alex Chilton. The sequence at its core – Scarecrow, Elvis Went To Hollywood, Cover Up The Sun – is a blast. So, Adam, what happened?

“It just felt really good to be writing again,” he replies. “I’d felt, not so much that I couldn’t write again, but a little trapped in the plot arc of where everything was going for me. As if, as much fun as we make of shows like Behind The Music for completely concocting this bullshit arc – they’re unknowns, and then they’re hugely famous stars, and then everything falls apart, and then they recover again – the truth is, people expect it.”

Did he feel that clichéd story was happening to him?

“To a certain extent. In any case, it felt like, after Saturday Nights And Sunday Mornings [the confessional 2008 album Duritz wrote at a terrible personal low], I didn’t want to be creative about my own shit any more. I thought, ‘Maybe I’m tired of being a musician. Maybe I’m tired of scraping my guts out for people.’”

Recording Counting Crows’ 2012 covers album Underwater Sunshine and writing songs for a play, Black Sun, that summer, offered him a new way forward. “The play showed me it was possible to write pieces that involve just as much of how you feel, without it being your story at all.” In autumn 2013, his band travelled from their West Coast homes to Duritz’s Greenwich Village house to get back to work. “In six days, I wrote five songs,” he remembers. “It was pouring out.”

“It was easier to make than some have been,” Crows keyboardist Charlie Gillingham agrees later, on the phone from California. “And you can hear that in Adam’s writing. All his other songs are complicated, coded messages about himself, his memories, his psychiatric issues. And on this one, he just wrote. He’s so brilliant, in the way he can put together images and ideas and characters and stories. It’s literature. It’s as complex as James Joyce, and it’s great to hear Adam write with that side of himself, and leave a lot of his baggage behind.”

A line in Earthquake Driver, ‘What is the price of this fame and self-absorption?’, seems to nail Duritz’s old style head-on. A note to self?

“A lot of that song is just me making fun of things,” he says. “Someone was bitching about the obviousness of it saying ‘I live alone but I’m hungry for affection/ I struggle with connections’ – does he have to relate his travails? That’s a joke, you idiot! And we joke about people being self-absorbed, but of course we want them to be that way, because who the fuck else is going to write songs for us, paint paintings, and sacrifice the rest of their lives to examining their own navels, so that everybody else can be entertained? Movies about artists are always about that shit, bland critiques of them not always being the best people. Who gives a fuck? Lots of people who are far less interesting than Mozart have bad home lives. But nobody ever explores, why would you paint a painting, or write a song?”

Why does he?

“Because it’s hard for me to directly connect with other people. So I write a bunch of songs, and hope it somehow sinks into somebody. The sort of problems other people work out in their everyday lives, I either don’t get them worked out, or I call it working out by writing songs.”

Somewhere Under Wonderland’s near eight-and-a-half minute first single Palisades Park, is an epic calling card for the resurgent Crows; a saga of two young people in the 70s that sounds like it’s come straight off an early Springsteen album. Duritz was thinking of Lou Reed and the Factory scene in the 60s, and the Dead Boys and Ramones at CBGB’s 10 years later. He was also drawing on vivid memories from the start of his own rock’n’roll journey.

“We moved from Texas to Northern California in the early 70s,” he remembers, “so I was growing up there in the late 70s. It was before Aids, and there was this whole segment of the population that had been living in other places and been brutalised, and told that everything about them was wrong, who all came out to San Francisco, where it’s okay to be who you are. I was fourteen in ’78, sneaking over there because they’re not checking IDs, so we can get drunk. And the sexuality part doesn’t register with me. But the freedom and the insane liberation of it does. People wearing drag, topless women. When I saw La Cage Aux Folles or Moulin Rouge later, that looks a lot like those bars when I was a kid. Everyone was really nice to us, they didn’t give a shit. I didn’t realise how hard and brutal it had been for a lot of these people, but I could see how great it felt at that moment, and that was a big thing for me.

“I was twenty-seven the first time anyone from a record company even looked at a band I was in, and twenty-eight when I got signed,” he recalls. “The ten years before that that were really terrifying. But I was also having rich experience in my twenties, and Palisades Park celebrates that – being on the fringes, wanting to try on the wrong sex’s clothing, and wanting to try PCP, which is a bad idea. But it’s about that experimentation.”

“Adam had a bad period [psychologically] in the late 80s as well as later, and that’s the man I met originally,” Charlie Gillingham recalls of Counting Crows’ start in the Bay Area, 23 years ago. “When the band began, here’s what I actually saw: one of our guitar-players, David Bryson, was a successful engineer who owned a studio. And he was helping this guy who didn’t look like he would ever be a bandleader. What he looked like was a genius who had these amazing songs, but it was unclear whether he would ever get his head together enough to start a band. Adam was playing with other people’s bands when David started this project to record these songs by this genius. And those became the demos for songs on the first record, and by the time we finished that record, it became clear that this was Adam’s vision. So Adam had to change who he was, to become an actual bandleader, and CEO of our small business, and that was hard for him. That’s one reason we’re slow making records. We’re a homemade thing.”

After a decade of struggle, Duritz suddenly found himself with famous friends ready to ease his band’s passage to the big time. He was invited to guest on Maria McKee’s 1993 hit album You Gotta Sin To Get Saved, then asked to play acoustically with Bryson in the middle of future August And Everything After producer T-Bone Burnett’s set at a high-profile charity gig at LA’s Whisky A Go Go. “All of the hipsters in Hollywood were there, and the LA Times flipped out on us afterwards. But the thing about those moments is, you just play, because there’s nothing else you can do. Or you can chicken out and fuck up. But we never did.”

Another new pal, The Band’s Robbie Robertson, was on hand with sage advice. The former inhabitant of (Bob Dylan’s retreat) Big Pink suggested they dispense with studio nerves by renting a house to record in. Then, when Van Morrison refused to play at his Rock And Roll Hall of Fame inauguration in 1993, Robertson suggested his unknown new acquaintances fill in.

“We ended up playing Van Morrison’s Caravan,” Duritz says. More turns for the bizarre followed. “At the rehearsal the day before, we’re in the room with The Doors, and Clapton, and Jack Bruce. At the show, I was the first person of my generation to see Cream play, with Danny my guitar-player on one side of me, and George Clinton on the other. That’s the George Clinton who became the first person to ask for my autograph! So we’re around some heavy cats. When we played that night, we sang the shit out of that song. And I walk off the stage and I am gassed, gone like I always am.”

It was in this state that Duritz found himself tangled the stage curtains and tripped and fell forward. “And I stopped, like fooomph And it was like I’d just fallen into this very soft, pillowy, bouncy castle. I didn’t know what it was, and I reach out, and I put my hands out and press up on something, and I realise as my eyes adjust that my head is planted between Etta James’s breasts! Which are voluminous. That’s the reason I didn’t kill myself. She’s sitting in a chair with k.d. lang behind her, my face planted in her breasts, and I lift myself off, I push myself out of it, and I just looked at her and she looked at me, and I’m stunned by the utter fucked-upness of it. And she says, [Southern drawl] ‘Y’all right, honey?’ I said, ‘Yeah. I’m okay.’ She said, ‘You sang real good.’”

When Mr Jones, a jauntily melodic hit about working musicians’ dreams of success, helped August And Everything After to phenomenal success, life became less amusing for Duritz. “It wasn’t just people yelling insults, and all those things that come with fame,” Gillingham explains. “It was the whirlwind of his entire life changing. He was responsible for us now. And suddenly there’s a girl lying in front of the bus insisting that she’s Anna [from the song Anna Begins], and asking us to run her over. And he’s getting letters from suicidal people who are convinced that his songs are written to them. Being famous really understates what actually happened to him. It’s not just the paparazzi.”

Like Eddie Vedder before him, Duritz’s early interviews could seem ungracious, as he complained about the success many of his fans dreamed of. “Everyone says they’d trade their lives for yours in a minute if they could,” he says, simmering at the thought. “Well they can. I remember what it took to do this, which was not to have any security, and to do a job with no promise of success whatsoever for ten years. A lot of my friends did it at the same time, and never had success with it, but they still did it. So don’t tell me you’d trade my life – because you didn’t. They did. The truth is, everyone can be in a rock band. It’s not like being an airplane pilot, where you have to pass a test. I can’t play very well. I don’t have that kind of talent. It’s hard to write songs. But I did it. And a couple of the songs on August And Everything After are incredibly prescient about what happened next. Mr Jones in particular - like, wow, good guess! I wrote Mr Jones when I wasn’t famous. That was a song about dreaming of being a rock’n’roll star, which is a perfectly legitimate thing to dream of. But it’s also about how that doesn’t fix your life. And then it didn’t, of course.”

“People ask me, after the success of the first album did you feel pressure on the second,” Duritz says of the US chart-topping Recovering The Satellites (1996). “But we made the first album before any of that success, with just us in a room. So the second album seemed fairly simple: go in a room with the same guys and make a better one. We already had songs like Goodnight Elisabeth. Really, it was the first album that was hard. Before it, we sounded like late-model Roxy Music, and there was an artificial sheen on what we were doing. I took away all of the Stone Roses Echoplex guitar effects – took away half the drums on Steve [Bowman]’s kit. And then took away Steve. Got rid of all Matt [Malley]’s fretless basses, got him an old Hofner Vox Teardrop. It was kind of brutal, and I still think that record has a sheen on it, that is probably what makes it so popular with other people. But it was not as raw as I wanted it to be. I was excited at the kind of record we were going to make.”

Success, though, had taken its toll. Duritz went home early from the August And Everything After tour, suffering from what was diagnosed as depersonalisation disorder, which makes people and events seem detached, unreal and often terrifying. He quit his Berkeley home for Los Angeles, where his new landlady showed how much his life had changed. “One of the bar-tenders at the Viper Room said ‘My friend’s moving, and she only wants to rent out to somebody she really likes, come and meet her…’ So she drove me up to [actress] Christina Applegate’s place…”

The Viper Room, the West Hollywood bar made famous when River Phoenix fatally overdosed outside, wasn’t just a place of sanctuary for the disoriented singer. He even started tending bar there. Was that an attempt to get back to normality?

“No, that wasn’t a very normal place!” he laughs. “This was as close as you’re probably going to get to what the Factory scene was like. It was great, crazy creative people. But the staff there were the only friends I had when I moved to LA, and one day the bartender Shannon said she had to go to the bathroom, could I tend the bar? I made enormous tips for her, so I started doing it every day. It was just a place to be with my friends, where I was comfortable. Because nowhere else was okay for me then. I would finish work, go to the Viper Room at five, and stay all night.”

It seemed there might be some ambiguity to his desire for anonymity, though, when his time in Hollywood was spent dating actresses including Jennifer Aniston and Courteney Cox.

“I did want anonymity,” he claims, “but you’re also meeting girls that you want to meet. I was really shy when I was a kid, so I didn’t get to date the cheerleader. And now the popular girls want to talk to me, and some of them are quite nice. I dated a lot of people, and they report the ones that are famous, and make up a lot of them.”

Following the harder-edged Recovering The Satellites, further Counting Crows albums were released infrequently, and with decreasing impact. There were highlights, of course, like the rollicking epic Mrs Potter’s Lullaby on This Desert Life (1998), or most of the reinvigorated, snappy, Steve Lillywhite-produced Hard Candy (2002). In any case, the band were content.

“Believe me, there are corporate sell-outs, and then there’s us,” Duritz says of their non-career plan. “When you sell ten million records with T-Bone Burnett producing [on August And Everything After], they do not want you to go find Gil Norton, who produced Pixies records, to do the next one. And when that’s Number One, they don’t want you to go find [David Lowery] the guy who did the Sparklehorse record. But we always had the balls to say no whenever anyone tried to interfere with us.”

In the period which inspired the songs on Saturday Nights And Sunday Mornings (2008), though, the mental illness which had been dogging Duritz all along laid him low. He was on tour in Perth, Australia, the most isolated city on earth, when he received two phone calls in quick succession, telling him the girlfriend he’d staked his life on was dumping him, and his grandmother was dead.

Duritz’s voice floats off as he remembers that day: “I was with this girl in Dublin, and for the first time in our lives we’d been able to make something work, and I didn’t want to leave. But I had to leave, because it’s my job to leave. I was getting very bitter about that. Then my grandmother died, and I realised I hadn’t seen as much of her as I wanted to in the last five years of her life. Because she was losing a lot of her faculties, and I looked weird, and I scared her. She didn’t quite understand that it was me. So I went home. I felt like I needed to be there for my mom. To do something for somebody else. Because when my dad’s mother died I was younger, I wasn’t a man. I wasn’t able to help.”

Duritz sought intensive medical aid for his illness, desperate for a cure. “I’m not sure these things get cured,” he believes now. “It turns out I can do some things, still. And whatever I went through in those years didn’t kill me. Although it can feel like being doomed. Because it’s not like other problems you’ve had, when someone else can get between you and it. When I was younger, if you’d told me I couldn’t write songs any more but I could be healthy, I’d say, ‘Fuck that.’ Because I thought that leaving a mark was the most important thing in life. Now, I don’t know. Maybe I would do that deal. But in any case, it’s not getting offered.”

“He has a reputation for being dark,” Gillingham says of his old friend, “but he’s a very charming, friendly, caring guy, very loyal, very good to people, who has a disease that occasionally makes him go completely dark. And he writes about it, and that makes the music dark. Touring exacerbates it. It makes the world seem even more unreal, because you wake up in a different bed every night. So at the beginning, the road was an alien planet full of monsters. Now, we stay on the tour bus and it’s home, I think. I was worried about Adam in the 2000s. My first worry was always about him, not the band. But he seems to be through the worst of that.”

Counting Crows, too, have a new lease of creative life. Do they deserve our renewed respect, this late in the day? Did they ever? Duritz doesn’t quite want to say.

“There’s going to be a point in your life when if you’re really, really lucky in a band all the zeitgeist works, and you are the centre of popular culture,” he says. “And we had that. It’s not because that record was better than other records. I don’t believe it is. Now this record is really good, years and years later, and it came out at Number Five or Six in America, which is pretty good for us now. But that’s 30,000 copies. We sold that every week for years, on the first record. That’s not going to happen again, because we’re not the centre of culture. But it doesn’t change the fact that it’s a really, really good record, which is what we set out to do - make a record that was really good, and then make another one and another one and another one, and here it is 21 years later, and this is a fucking great record. And as far as the respect thing - I’d feel like a child, really, if I were to complain too much about that.”