In August 1976, Epic Records launched Boston’s self-titled debut album with a bold advertising slogan: “Better music through science.” Tom Scholz, the group’s leader, thought that was bullshit.

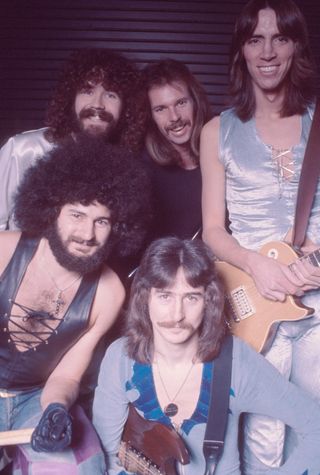

Scholz was no ordinary rock musician. A graduate of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he was still employed as a product design engineer for the Polaroid Corporation when the Boston album was released. He had created the album in a basement studio that he had built himself, using new recording technology that he had invented. He worked mostly alone, obsessing over every detail in the music. And he did this for more than five years before the album was complete.

What Scholz had created was a groundbreaking album: hard rock elevated to a new level of melodic sophistication and state-of-the-art production. But he hated that slogan. “I thought it was a terrible reflection on the album,” Scholz says now. “I can’t argue that I put my technical background to work when I was trying to make the record. But the music itself had nothing to do with science. Music was my escape from that world.”

Scholz wanted the ads pulled and made this clear in a heated exchange with Walter Yetnikoff, then President of Epic’s parent company CBS Records International. It was the first shot in a war between the two men that would lead to a courtroom battle in a landmark case for the music industry. But Yetnikoff wouldn’t back down over the ads. And that slogan would stick like glue to Tom Scholz.

“The mad scientist in the basement,” he says. “That was something that Epic really cultivated in the early days.”

But, 37 years on, as a new Boston album, Life, Love & Hope, is released after 11 years in the making, Scholz accepts the truth in it. “The fact is I do work in a basement. So that part of it is accurate. A scientist? I do have a couple of degrees. Whether that makes me a scientist or not I’m not so sure. What I do is I like to design things – to come up with things that solve a problem. And in this case I did come up with some gadgetry, things that people called ‘wizardry’. Mad? I suppose some people would think so. So I suppose it’s not altogether undeserved.”

He pauses momentarily and laughs.

“I’m not even sure that I don’t like it, to tell you the truth.”

Tom Scholz can laugh off the notion of being the mad scientist of rock’n’roll. It’s harmless enough – it implies nothing more than eccentricity. But the new Boston album comes at a time when Scholz has been the subject of much negative publicity.

Throughout 2013 there were media reports of three lawsuits involving Scholz. On April 19 it emerged that he is suing former Boston guitarist Barry Goudreau for alleged trademark infringement. According to the Boston Globe, the lawsuit claims that Goudreau, who left the band in 1979, signed an agreement awarding him 20 per cent of royalties from the first two albums in return for giving up all rights to the name ‘Boston’. Goudreau, it is alleged, broke this agreement with promotional material in which he is referred to as ‘Barry Goudreau from Boston’.

A similar story emerged on August 21, when the Boston Herald reported that a federal court judge had ruled against Scholz in a dispute with Fran Cosmo and his son Anthony. Scholz had attempted to prevent the pair from advertising themselves as ‘former members of Boston’ – despite the fact that Cosmo Sr was the lead vocalist on Boston’s 1994 album Walk On, and his son was a guitarist and songwriter for the band between 1999 and 2004.

And on July 1 it was revealed that Scholz had been ordered to pay the Boston Herald $132,000 following the failure of a defamation lawsuit against the newspaper. Scholz had sued after the Herald ran a story on the suicide of original Boston singer Brad Delp. Using quotes attributed to Micki Delp, the vocalist’s former wife, the story alleged that the relationship between Scholz and Brad Delp had resulted in Delp being “driven to despair”. It was headlined: ‘Pal’s snub made Delp do it: Boston rocker’s ex-wife speaks’. A Superior Court judge ruled that the Herald could not be held liable for defaming Scholz because it was impossible to know what caused Delp to kill himself.

In the wake of these reports, Scholz is cautious when engaging with the media. Before he will talk to Classic Rock, Boston’s UK PR emails the following request: “Please do not ask any questions about Brad Delp’s suicide, and do not ask Tom any questions about former original members of Boston. These are two talking points he does not want to discuss.” By implication, Scholz will also not talk about the defamation lawsuit he lost to Herald.

But he will talk about Brad Delp – not least because Life, Love & Hope includes three tracks on which the late vocalist features. He will happily discuss the best times he shared with Delp during the early days of Boston’s career. And he doesn’t duck questions about his own reputation as one of the most difficult and confrontational artists in the music industry.

On the phone from his home in Massachusetts, Scholz speaks quietly in a low voice with a soft accent. His words are carefully weighted. With a new Boston album to promote, he considers press interviews to be a necessary evil. “You could look at it that way,” he says. “It is also, however, a chance to tell my story. It’s not all evil – there’s some good.”

Born in Toledo, Ohio on March 10, 1947, Donald Thomas Scholz was 29 when the first Boston album passed the million sales mark in November 1976. Ever since, he has remained a divisive figure.

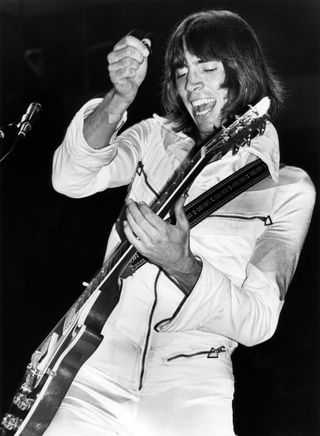

On an artistic level he is a purist and a visionary. Boston’s 1976 hit single, More Than A Feeling is one of the most perfectly crafted rock’n’roll songs ever recorded: beautiful, uplifting, complex and unique. It helped turn their self-titled debut into one of the biggest-selling LPs of all time (20 million copies to date) and set the template for the entire AOR genre.

But what makes Scholz’s music so unique – that intense focus and singularity of vision – is also what has led him into conflict with those he has worked with. Scholz is a true maverick, an artist who makes music his way or not at all. This has defined his life and Boston’s career. And it has led to clashes with some of the industry moguls who courted him as a prized, money-making asset.

John Kalodner is the high-profile A&R man who revived the fortunes of Aerosmith and Whitesnake in the 1980s, and worked with Scholz on Boston’s 2002 album Corporate America. Kalodner later revealed the nature of his working relationship with Scholz to Classic Rock: “Each day he would pick me up in his stupid Honda car and drive me to the studio, and drive me back to the same shopping centre again in the evening. He was so paranoid, he didn’t want me to know where he lived. And we were trying to make a record together! I love his music, and he’s so talented, but he’s almost impossible to work with.”

Today Scholz is outspoken in his loathing for the music industry. “Of all the entertainment businesses, including television and movies, the music business is the worst of all them,” he says. “It attracts the lowest form of life in many cases.”

This sensibility was formed at the height of Boston’s success in the late 70s, when Scholz became embroiled in a dispute with CBS boss Walter Yetnikoff. Scholz was a hippie, a vegetarian and a sensitive soul who put art before commerce. Yetnikoff, by his own admission, was a hard-drinking, cocaine-snorting tough guy who liked to play hardball. For all the money that Boston was making for CBS, the pair butted heads. “He told me from time to time that I could go fuck myself,” Yetnikoff said of Scholz. “He’d complain about the colour of the sky, all sorts of things.”

This hostility came to a head over the band’s second album, Don’t Look Back. Following the success of Boston, which sold eight million copies in two years, Yetnikoff leaned on Scholz to get the next album finished as quickly as possible. In fairness to Yetnikoff, Boston’s contract with Epic – signed by Scholz and Brad Delp – was reportedly for 10 albums deliverable in six years, which was industry standard in the 70s. Reluctantly, Scholz finished the album in time for a 1978 release. But, as he says: “I’ve certainly not hidden the fact that it was released, in my opinion, before it was complete.”

Don’t Look Back sold four million copies – by any normal standards, a huge hit. But it was only half of what the first album sold. Scholz vowed that he would never again be forced into releasing an album before he felt it was ready. The result was a standoff between him and Yetnikoff. And if Yetnikoff believed he was an irresistible force, what he met in Scholz was an immovable object.

By 1983, five years after Don’t Look Back, Yetnikoff and CBS were still waiting for a third Boston album as Scholz tinkered endlessly at his new home studio (in a basement, of course). The guitarist was notified that Boston’s royalty payments from the first two albums were to be suspended. Scholz made his position clear in a letter to Yetnikoff: “Apparently some people at Epic feel I should be punished for my refusal to sacrifice quality and deliver a record that’s compromised by haste. In fact, I will never foist a second-rate record on the public to fill CBS’s pockets or my own.”

CBS sued Scholz and the band for breach of contract. But it was the guitarist who emerged victorious when, finally, Boston’s Third Stage album was released in 1986 on a new label, MCA.

“It was a landmark case,” Scholz recalls now. “I never set out to be any sort of crusader when it came to cleaning up the record business, but somehow it ended up happening.”

Third Stage went on to sell four million copies and yielded a US No.1 single in Amanda. If ever an artist stuck it to The Man, it was Tom Scholz.

Walter Yetnikoff and John Kalodner are not alone in thinking Tom Scholz is a difficult man to work with. Michael Sweet, the singer for Christian metal band Stryper, was a member of Boston’s touring line-up in 2008. He says that he and Scholz enjoyed a close friendship. Nevertheless, Sweet describes him as “very intimidating… Tom is an extreme perfectionist,” he says. “I’m OCD, but he takes it to a new level.”

When questioned on the subject, Scholz is prickly: “When I’m recording, I pretty much work alone. But I would say, since you put me in the uncomfortable spot of trying to defend my reputation in terms of how easy or how hard I am to work with, I have an awful lot of glowing thank-you cards from the musicians and crew that I’ve worked with on Boston’s tours.”

Scholz is not inclined to self-analysis – at least not publicly. “I’m not that well versed in psychological matters,” he says. But for as long as he can remember, he has been intensely focused and goal-driven. “I’ve always approached everything with the thought that if I’m gonna do it, I’m gonna do it as best I can.”

His creative process – in which he works in isolation as writer and arranger, multi-instrumentalist, engineer, producer and problem-solver – exhibits all the traits of a confirmed control freak. His reasoning for this is simple: “Why would you ever let go of something that has worked for you – that has brought your art to a level that you finally are happy with? I don’t think any self-respecting artist would back off from what he had to do, just because it was hard to do. That would be a horrible cop-out. Other than the people in my life, the art is absolutely the most important thing.”

He explains why he has to work in complete isolation: “I don’t listen to any music other than the project that I’m working on. I can’t listen to other music or I would be influenced by it, even if it was just subliminal.” He claims that he hasn’t bought an album since before the first Boston record was released. “The last time I bought an album and listened to it was probably 1973. Jeff Beck’s Truth, the second Led Zeppelin album and James Gang Rides Again – that was the last one.”

He doesn’t buy new recording equipment either. The new album was recorded in the studio where he made Walk On and Corporate America, with the same old analogue tape machines he used on the first album. “This gear I’ve used pretty much since the beginning,” he says. “The 24-track is 35 years old and still going strong. I especially love stuff that works well and then gets old. That includes my car, which is 17 years old, and a single-engine airplane that I’ve been flying for 32 years. Even my telephone is 30 years old.”

One of his favourite pieces of recording kit is the Rockman, a headphone amplifier of his own invention, originally produced via his company Scholz Research & Development, Inc. The Rockman, which combines multiple guitar effects, was instrumental in the creation of Boston’s signature guitar sound and was subsequently used by other artists including Def Leppard. And there was an added benefit for Scholz: when Epic withheld his royalties during the making of Third Stage, the profits from the Rockman allowed him to hire a top attorney to fight his case.

He can laugh about some of his eccentricities in relation to his painstaking modus operandi. In fact he laughs a lot during our conversation. At odds with his serious reputation, he is a witty and engaging interviewee. Asked if he has empathy with Axl Rose, who spent 14 years making Guns N’ Roses’ Chinese Democracy, there is more laughter. He knows that he is again demonstrating how out of touch he is in relation to modern rock.

“I have to apologise for my ignorance here,” he says. “I know who Axl Rose is but I’m not familiar with Chinese Democracy.”

He accepts that 11 years between albums is a long time. When the previous Boston album, Corporate America, was released in 2002, the war in Iraq had not yet begun. But this is the only way he can work and be happy with it – even if, as he admits, this work ethic comes at a huge personal cost in terms of time and losing out on things he would love to do with his family. The new album was interrupted by four lengthy tours. But he still put an enormous amount of time into it.

“Most of the time I work every day,” he says. “Typically at least 40 hours a week and usually quite a bit more than that. It will often go on late into the night when I’m recording. You work when it’s happening, when you’ve got the idea, when you’re hot. When things are falling your way, you don’t stop. So it doesn’t matter if you’re tired, it doesn’t matter what time it is, it doesn’t matter that it’s Sunday or Monday or Thanksgiving or what it is. You’ve got to do it. It’s a constant effort.”

He describes his wife Kim as “extraordinarily patient”. They have been together nine years and married for five. “I don’t take anything that you would call a vacation,” he says. “We go away once in a blue moon for three days here or there. There are a lot of things that I’ve missed out on – things that I would love to be doing, like hiking up a mountain or freestyle skating. But most of my time gets spent on music, to the exclusion of all those other things. The cost in terms of my personal time to make an album is very high. And it is not taken lightly.”

For all his friendliness, it’s understandable that Scholz declines to discuss the death of Brad Delp. It’s a difficult subject for anyone connected to Delp to talk about. Even more so for Scholz, following his failed defamation lawsuit.

It was on March 9, 2007, a day before Scholz’s 60th birthday, that Delp was found dead at his home in Atkinson, New Hampshire. His body was discovered in a bathroom, which he had made airtight before lighting two charcoal grills. The cause of death was carbon monoxide poisoning. A suicide note was attached to his T-shirt. It read: “Mr. Brad Delp. J’ai une ame solitaire. I am a lonely soul.” He was 55.

Five years later, during the course of Scholz’s lawsuit against the Boston Herald, came new revelations about the events that led to Delp’s suicide. It was reported that Meg Sullivan, the sister of Delp’s fiancée Pamela Sullivan, had been living at the singer’s house. Nine days before Delp’s suicide, Meg Sullivan had found a hidden camera in her bedroom. Delp confessed to placing the camera in the room and emailed an apology to Meg, in which he said: “I feel sick about this, and deservedly so. I want to try and make you understand that I consider myself a decent person who made a dreadful error in judgement. I acted out of some impulse that is still not completely fathomable to me.”

Scholz has made it clear – via his management and PR – that he will not address directly the death of Brad Delp or the repercussions that have played out in the media and the law courts. What he will discuss is Delp’s role on the new Boston album, and the memories he has of the man whose high tenor voice lit up More Than A Feeling and so many other classic Boston songs. He says that Delp’s performances on Life, Love & Hope were recorded over a lengthy period. One song, Sail Away, was cut in 2002. The other two, Didn’t Mean To Fall In Love and Someone, were completed in 2005. This is typical of Boston. “Every song on every album will materialise over a period of years,” says Scholz.

Delp had an on-off involvement with Boston, though Scholz says that he always had an open invitation to sing on his songs. “But he was always a free spirit. He came and went three times. But when he felt like singing with Boston, he always did a great job.”

This much, Scholz seems comfortable with. But when asked if he had any reservations about using Delp’s vocals on this new album, he hesitates. At this point, another voice comes on the line – a representative of his management company, who has been monitoring the conversation without Classic Rock’s knowledge.

Management representative: “Hey Paul, we’re getting kind of tight on time. Can we move on to another topic – the next question?”

Classic Rock: “If we’re tight on time, can I just finish talking to Tom about what I choose to speak to him about – unless you want to censor me?”

Management representative: “No one’s censoring you. Go on.”

Classic Rock: “I’m aware that there are issues that Tom doesn’t want to speak about, so I’m not going to speak about them.”

Management representative: “Okay. Then proceed as long as you know. We’re all good.”

Classic Rock: “Tom, if you have a problem with me asking you a question, you let me know.”

Scholz: “Paul, what’s your question?”

The question is repeated: did you have reservations about using these tracks with Brad’s vocals on this new album? Was it a difficult decision emotionally for you to make?

“Not at all,” Scholz says. “I think Brad would have been pleased to know that his vocals had been included on an album with such an optimistic outlook. I think that if he were alive to see it and his vocals had been left off, he would have found it very upsetting. The thought of leaving them off never occurred to me for one instant.”

A difficult moment passed, Scholz has something else to say about Brad Delp. When Scholz was creating the first Boston album, Delp was his sole collaborator. Before the band was formed, Scholz and Delp were Boston. Scholz couldn’t sing. He needed a great singer, and that was Brad Delp.

“Working with Brad was always a lot of fun,” he recalls. “Of course there were times in the studio when we would have different ideas and would knock heads, but most of the time we were just really enjoying music. And he was constantly joking. He would have me in stitches half the time – we’d be in the middle of a song, the tape was running, and he would go off on an impersonation of some singer or comedian.”

In those early days, the two men had what Scholz describes as a telepathic understanding. “We had almost a Vulcan mind link. When we were working we spoke in shorthand terms. We didn’t hang out when we weren’t working. On the other hand, we spent years together on the road. He was a vegetarian like I was, so we ate meals together. When you add up all those many tours, it was a lot of time to spend with someone. Brad was a very funny guy. He kept me and everybody else laughing most of the time.”

This impression of Brad Delp is widely held by those who knew him well. Massachusetts-based drummer John Muzzy was a friend of the singer for more than 20 years. On Boston’s Third Stage tour, Muzzy’s band Farrenheit were the opening act. And from 1994 to 2007, Muzzy and Delp performed together in a Beatles tribute act named Beatlejuice – something that Delp referred to as “my hobby”.

“Brad was such an open, generous person,” Muzzy says. He acknowledges that Delp was a complicated man, and recalls him quoting a line from Woody Allen’s 1977 film Annie Hall: “I just don’t want to belong to any club that would have someone like me for a member.”

“Brad would joke about that,” says Muzzy, “but I think he also felt like that. He did not have very good self-esteem.”

Muzzy will not confirm that Delp suffered from depression. “It’s more complex than that,” he says. He recalls a conversation in which he asked Delp if, at the height of Boston’s fame in the 70s, he ever thought, ‘Man, I’m happening!’ Delp replied: “No. Actually what I thought was, ‘Boy, I have to be a lot nicer now.’” This, Muzzy believes, was evidence of Delp’s deep concern over how he would be perceived by his friends and fans. “As I reflect on these things,” he says, “that’s pretty telling.”

Shortly after Delp’s death, Muzzy emailed Tom Scholz to offer his condolences. “I really felt bad for Tom,” he explains. “Tom and Brad had their own unique relationship. That started when they were in their early twenties. And you can’t help but mourn the loss of a certain innocence.”

Muzzy says that he and Scholz do not have “a friendship”, but he retains fond memories of Scholz from the Third Stage tour. “Tom was so unbelievably generous to our band,” he says. “Halfway through that tour, we were out of money. We said: ‘We’re not able to do any more.’ So he gave us a raise. That was something I will never be able to repay.”

Certainly Muzzy holds no grudge towards Scholz. “Even from my limited conversations with Tom, I know he’s a very sensitive guy,” he says. “I don’t think that anything he does is based on being malicious.”

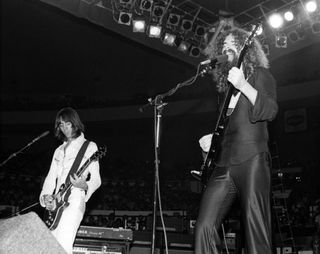

On August 19, 2007 a tribute concert in honour of Brad Delp was staged at the Bank of America Pavilion in Boston. It featured various local bands, including Extreme and Godsmack. John Muzzy performed with both Beatlejuice and Farrenheit. Barry Goudreau appeared with his two post-Boston groups Orion The Hunter and RTZ, the latter having featured Delp. The show finished with a performance from Boston, in which Scholz was joined on stage for the closing song, Don’t Look Back, by Goudreau and another former member of the band’s classic 70s line-up, bassist Fran Sheehan. Drummer Sib Hashian declined to appear.

With many of Delp’s family in attendance, the tribute concert was an event that Muzzy describes as “wonderful and very emotional”. But he remains perplexed by the continuing problems between Scholz and Goudreau.

“I don’t get it,” he sighs. “I know Barry, I know Tom, and I wonder why there has to be these issues. What a shame. I wish things were simpler, because, you know, life is over so fast, as evidenced by Brad being here one day and gone the other. Him taking his own life was devastating. Really, I’m still in shock.”

Tom Scholz still believes that music can be a life-changing force. In that respect, he hasn’t changed in all the years since he was locked away in that tiny basement working on the first Boston album. This is the central paradox of Scholz’s working life: while hidden away from the world, he makes music that would reach out to millions.

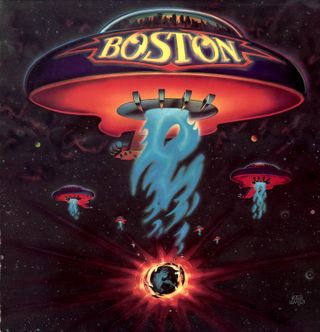

The title of his new album, Life, Love & Hope, is an extension of a message that has been at the heart of Boston’s work from the very beginning. “What I always hoped,” he says, “is that my music would be an escape vehicle for other people, like it is for me.” He refers back to the cover artwork for Boston’s debut album – an image of a guitar-shaped spaceship lifting away from a dying planet.

“That was my idea. I wanted an escapist theme because music was my escape – that was my whole purpose for being involved in music. And the new album fits that theme completely. Life, love and hope – these are the things that are most important. And yet, due to the practicalities of everyday life, people so easily lose sight of that. What I hope is that the music on this album will leave people in a more optimistic frame of mind. That is what Boston has always been about.”

Scholz says his songs are “designed to elicit emotion”. This has not always been understood, due in no small part to that maligned slogan: ‘Better music through science.’ He recalls an interview with a journalist from Newsweek in the late 70s: “This reporter was questioning me at great length about how I could assure her that my songs actually were not written with a computer program,” he laughs. “She had been told so in some ‘inside scoop’. And even in her article, she presented it not that they weren’t, but that I denied that they had been written by a computer program.”

There are other urban myths about Tom Scholz that have been repeated over the years, such as the story about him re-recording a drum track 700 times during the making of the first album. “I’ve never heard that story,” he says. “But I can certainly say there were no drum tracks recorded 700 times. There were a couple that required quite a few takes, but the most that I remember was 17.”

What is undeniable is that Scholz has managed a small return in terms of music for the amount of time he has devoted to Boston: six albums in almost 40 years. “It’s what I was able to do,” he says. “And I consider it better than zero. If there had just been one, I would have said I was already ahead of the game.”

He says that if he’s lucky, he will make two more Boston albums. “It’s very unlikely that I’ll live to 110. If you figure 11 years per album, I’ve probably got at the very most three left in me.”

Looking back at his life, Scholz says that music is not the greatest part of it. “My wife, son and dog come way before the music. But if my house was burning down and everybody was out, yeah, I’d run back in to grab the tapes.”

Tom Scholz knows that many would consider him mad. “I think that anybody that spends a significant portion of their life on any project, a lot of people would consider pretty crazy,” he laughs. “Making music is very frustrating sometimes, but there are times when it is quite sensational. When things happen for me with the music that I’m working on, it makes everything worthwhile. I have sacrificed an awful lot, but the music is very rewarding. And I’m not speaking of the financial aspect or the fame or anything like that. I’m just talking about the music itself.

“Because of the amount of time that is required for what I do, it has limited a lot of parts of my life. That is unfortunate. But this was the choice I made. And I don’t have any regrets.”

Life, Love & Hope is out now on Frontiers.

MAJOR TOM

There’s more to Boston than More Than A Feeling…

BOSTON (Epic, 1976)

Boston’s debut is one of the biggest selling albums of all time, indisputably a rock classic, and Tom Scholz’s masterpiece. All eight tracks are great, but the big one is, of course, More Than A Feeling. It remains the band’s definitive song, made perfect by Brad Delp’s emotionally charged vocal.

Standout track: More Than A Feeling

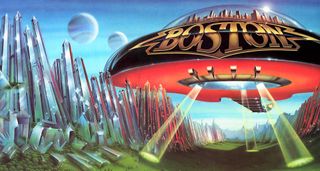

DON’T LOOK BACK (Epic, 1978)

Although Scholz considered this second album “incomplete” as a result of his hand being forced by the band’s record company, it still sold four million units. And it features three genuine Boston classics: the euphoric title track, monumental power ballad A Man I’ll Never Be, and balls-out rocker Feelin’ Satisfied.

Standout track: A Man I’ll Never Be.

THIRD STAGE (MCA, 1986)

Eight years was an extraordinarily long time between albums, but Third Stage was worth waiting for. The second-best Boston album, it was another huge hit, with the ballad _Amanda topping the US chart. Essentially a concept album about the journey into adulthood, Third Stage_ is where AOR meets art rock.

Standout track: Can’tcha Say/Still In Love

WALK ON (MCA, 1994)

With Brad Delp absent, Scholz turned to Fran Cosmo, previously the singer in Orion The Hunter alongside ex-Boston guitarist Barry Goudreau. A surprising move – but it worked. Boston’s sound remained virtually unchanged. And while nobody could match Delp, Cosmo was brilliant on Livin’ For You, Scholz’s greatest love song.

Standout track: Livin’ For You

CORPORATE AMERICA (2002)

For Scholz, Corporate America was “an experiment that didn’t work”. Delp returned to share lead vocals with Cosmo. More surprisingly, Scholz used three songs written by Cosmo’s son Anthony. But the album was largely forgettable – save for the title track, a fiery protest song by Scholz, with a modern rock flavour.

Standout track: Corporate America

LIFE LOVE & HOPE (Frontiers, 2013)

The new Boston album features five different lead vocalists, including Delp and, for the first time, Scholz himself. What holds it all together is that trademark Boston sound – the rich vocal harmonies and stacked guitars, created as only Scholz can. Sail Away, beautifully sung by Delp, is a fitting epitaph.

Standout track: Sail Away