“What do you think I’m going to do? Blow my brains out?” These were allegedly Terry Kath’s final words before he accidentally put a bullet in his head in 1978.

It was never meant to end like this. A fatal gunshot wound. Blood on the walls. A dead body.

Lee Loughnane, trumpet player with the US rock band Chicago, vividly recalls January 23, 1978. It was the day his friend, Chicago’s guitarist Terry Kath, shot himself dead after a game of Russian roulette went horribly wrong.

“I took a call from our manager, who said: ‘Lee, are you sitting down?’” Loughnane says now. “He told me what happened. But I had to see for myself. They’d taken Terry’s body away, but there was blood everywhere.”

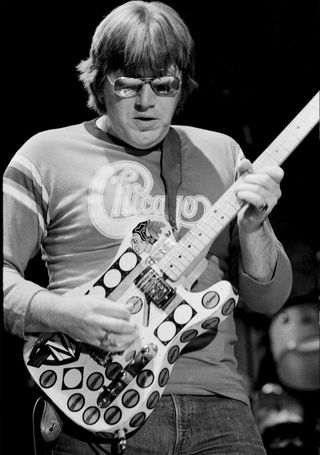

Terry Kath was just a week shy of his 32nd birthday when he accidentally killed himself. A singer, songwriter and wildly adventurous guitar player, Kath was the bedrock of Chicago, the daredevil group who had been meshing rock, jazz and classical styles across 11 hit albums since 1969.

Prior to his death, though, Kath’s love of booze and cocaine was impacting on his talent and his judgment. Kath’s accidental shooting was a tragic final act for a husband and father, and a musician once described by Jimi Hendrix as “better than me”.

Chicago are still touring and making music. Their last album, Chicago XXXVI: Now, appeared in 2014. But the memory of Terry Kath is in danger of fading with each passing year, which is why in 2012, Kath’s daughter, Los Angeles club DJ Michelle Sinclair, decided to try to make a crowd-funded documentary about him. The result of her work, Searching For Terry: Discovering A Guitar Legend, was released in 2016.

“I wanted to discover more about my dad and preserve his legacy,” says Sinclair, who was just two years old when Kath died. “But also because whenever you see those lists of Top Ten guitarists, he’s never on them.”

Terry Kath is still the greatest guitarist most people have never heard of. Before Chicago’s sugar-coated 80s ballads, there was the freewheeling Chicago of the late 60s and 70s, best sampled on A Hit By Varese, Dialogue (Parts 1 & 2) and the massive hit 25 Or 6 To 4. Back then, Chicago albums featured wailing horns, grooving Hammond organ and head-spinning time signatures, all harnessed by Kath’s howling lead guitar.

Terry Alan Kath was born in Chicago on January 31, 1946. His father, Ray, and his mother, Evelyn, loved music. “They ran a lodge and enjoyed entertaining people,” says Michelle. “That desire to bring people together and entertain them has been a generational link in our family.”

Kath learned to play piano, accordion and banjo, and inspired by the instrumental combo The Ventures and jazz musician George Benson, took up the guitar. By the age of 19 he was playing bass in local act Jimmy Ford And The Executives, where he met two future Chicago members: sax player Walt Parazaider and drummer Danny Seraphine. “I was running with a gang and Terry pulled me off the streets,” Seraphine says now. “Once I got that gig, my life changed.”

Seraphine remembers that Kath exuded a “charisma that intrigued me from the beginning”. At six-foot‑two, the burly guitarist with size 12 feet and a lazy grin was difficult to ignore. “He always reminded me of Robert Mitchum,” says the drummer. “A real man’s man.” But Seraphine also got a strong sense that there was “something darker” lurking beneath the happy-go-lucky guitarist’s smile.

A year on, the trio had joined The Missing Links, where they met Lee Loughnane. “Terry had that gruff exterior, but he was a pussycat inside,” Loughnane says, recalling their first meeting. “And he was never without his guitar. I don’t think I ever saw that thing in its case.”

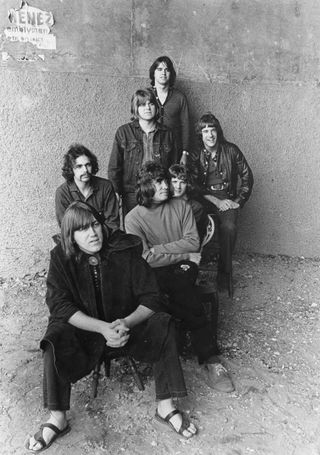

In 1967, Kath, Loughnane, Seraphine and Parazaider teamed up with trombonist Jimmy Pankow, vocalist/keyboard player Robert Lamm and, finally, vocalist/bass guitarist Peter Cetera and renamed themselves The Big Thing.

It was the era of Sgt Pepper, the Vietnam War and LSD. Artistic boundaries were blurring. For a club band, though, it was still smart suits and Top 40 covers. In protest at these restraints, Kath showed up one night with his suit jacket worn backwards. When The Big Thing played the Mothers Of Invention’s How Could I Be Such A Fool, a Milwaukee club owner fired them on the spot. “The music we wanted to play was rock’n’roll with horns,” says Loughnane.

By now, the band had come to the attention of ambitious songwriter/producer James Guercio, who had just written pop duo Chad And Jeremy’s US hit Distant Shores. Guercio signed them to his production company, brought them to Los Angeles and changed their name to Chicago Transit Authority.

In 1968, Chicago Transit Authority signed to Columbia and were soon recording their debut album, with Guercio (who also controlled their management and publishing) producing. “Jimmy was great, but Jimmy was a walking conflict of interest,” says Loughnane.

Released in April 1969, the Chicago Transit Authority double LP distilled a dizzying array of styles, most of them in its six-and-a-half-minute opener, Introduction, written by Kath and sung in his wonderful bluesy baritone. “The best opening cut on any album ever,” states Seraphine.

The album also included Kath’s dissonant, one-man mini-symphony Freeform Guitar. “Classical stations played that track,” says Loughnane. “But Terry was doing all that stuff Hendrix was doing before we heard Hendrix do it.”

As Kath told Guitar Player magazine in a rare interview in 1971: “Jimi was playing all the stuff I had in my head. I couldn’t believe it when I first heard him.”

CTA supported the album’s release by opening for Hendrix and Janis Joplin in the spring of 1969. The band had first encountered Jimi and The Experience’s drummer Mitch Mitchell when they dropped by their gig at the Whisky A Go Go. According to Walt Parazaider, it was here that Hendrix told him, “Your guitarist is better than me.”

“That’s been Walter’s soundbite for years,” Loughnane chuckles, while Seraphine adds to the myth by recalling how Hendrix and Mitchell came backstage at The Whisky and told CTA: “You are the best band I’ve ever heard in my life.”

“Hearing that wasn’t just good for our egos,” he adds. “It was good for our souls.”

As the band’s lone guitarist, competing with three horn players, Kath knew how to make his presence felt. Trombonist Jimmy Pankow recalls how even in their club days, Kath was “banging his guitar off his amplifier” – Pete Townshend-style – “to make it talk”.

As well as being a phenomenal rhythm player, Kath was ceaselessly inventive on stage and in the studio. He did it all: wah-wah pedals, distortion, endlessly sustained notes and the two-handed tapping heard on Freeform Guitar that would become Eddie Van Halen’s trademark in the mid-70s. “He had a sound that no other guitar player could get,” marvels Eagles guitarist Joe Walsh in Searching For Terry. “How in the world did he get a guitar to sound like that?”

Great as it was, Chicago Transit Authority wouldn’t budge beyond No.17 in the US, although it cracked the Top 10 in Britain. It didn’t help that James Guercio’s other new signing, fellow Columbia “rock’n’roll with horns” act Blood, Sweat & Tears, had just hit No.1 with their second album. “But Blood, Sweat & Tears didn’t have our songs, or our guitarist,” states Seraphine.

Undeterred, Guercio changed their name to Chicago (after the actual Chicago Transit Authority threatened them with legal action) and sent them back to the studio.

Chicago II arrived in January 1970, complete with Ballet For A Girl In Buchannon, a near 13-minute piece split into seven movements, encompassing film soundtrack-style instrumentals, and beginning with Kath’s Make Me Smile. But the album’s other hit-in-waiting was 25 Or 6 To 4, a Robert Lamm song that captured every facet of their sound: musical virtuosity, melodic nous and Terry Kath’s hooligan guitar. No sooner was the album out than Chicago were on a brand new Boeing 747 on their way to Europe.

At their Royal Albert Hall gig in London, each band member was introduced separately and received a standing ovation. Interviewed for an NBC news story in 1970, James Guercio declared: “If Johann Sebastian Bach were alive today, he would probably be performing in a band similar to Chicago.”

“On that first UK trip, we felt like we were true artists, not just a pop commodity,” wrote Seraphine in his 2011 memoir, Street Player. Not that this artistic validation ruled out the usual rock’n’roll misadventures. “There was women, booze, drugs,” admits Loughnane. “We were kids, ferchrissakes.” Seraphine himself flew home to discover that the late nights and overindulgence had left him with tuberculosis.

Back in the US, Chicago finally got their break when an edited version of Make Me Smile reached the Top Ten. “At first we were upset that Columbia were bastardising our music,” admits Loughnane. “But then we realised we were getting played on the radio.”

It was Chicago’s first but by no means last experience of art-versus-commerce. When an edited 25 Or 6 To 4 went Top Five in the US and the UK, though, nobody could complain.

So began a relentless cycle of album/tour/album that Lee Loughnane now marvels at. “Thank god we had so many writers in the band as we were constantly on the road,” he says.

Although America had embraced them, Britain’s love affair with Chicago had cooled. On a return trip to the UK, Kath’s gruff persona got the better of him during a press conference at the London Hilton. Weary of the praise journalists were heaping on home-grown guitarists Eric Clapton and Jimmy Page, Kath slagged off Clapton (“He sucks!”) and shouted: “Fuck you England, you motherfuckin’ teabag faggot motherfuckers!”

“That queered us,” says Seraphine. “We were so embarrassed. We took Terry aside and said, ‘My God, did you really just say that?’ But Terry could be very outspoken.”

Recorded in the summer of 1970, Chicago Live At Tanglewood, an unofficial but readily available album and film, offers the perfect snapshot of their outspoken guitarist. Kath, his lank hair flying, resembles a linebacker with an electric guitar. He grins, he sways, he shuffles, he rips out an astonishing solo on 25 Or 6 To 4, and he looks like the boss.

“Terry was the musical leader,” confirms Loughnane. “When you took solos, you’d listen for Terry’s whistle. It was high-pitched and permeated any decibel level. That whistle was the sign that you had eight bars left, and then it was time to go back into the bridge.”

Chicago V arrived in July ’72 and gave the band their first US No.1. Songs such as Dialogue (Parts 1 And 2) and Saturday In The Park hit a new peak. But a planned Japanese tour was postponed when Robert Lamm was taken ill. The entrepreneurial James Guercio was now directing a movie, Electra Glide In Blue, about an Arizona motorcycle cop’s run-in with local hippies. Guercio suggested Loughnane, Kath, Parazaider and Cetera play the hippies. “After all, we were hippies,” says Loughnane – and it meant Guercio didn’t have to pay real actors. The film soundtrack featured the exquisite Kath-sung ballad Tell Me. But in a chilly omen of gun-related events in real life, Kath’s character shoots a cop.

By January 1978, Chicago had split from “the man who controlled everything”, James Guercio, and had appointed a new manager. “Chicago was still an amazing band, but it wasn’t such a happy band,” admits Seraphine. “There was the constant pressure to write hits, and Terry was frustrated.”

Seraphine admits that some band members weren’t getting on, and that Peter Cetera’s “level of self-confidence” had been an issue for Kath as far back as 1968. Cetera is also the only member of the original Chicago not to participate in the Searching For Terry film.

Did Kath plan to leave the band? Lee Loughnane thinks not, but says the guitarist was planning to record a solo album: “And that might have helped ostracise some demons.”

In Terry’s private life, his volatile marriage to his first wife Pamela Robinson had ended, and he was now with Camelia Ortiz, whom he’d marry the following year. Their daughter, Michelle, would be born two years later. But the partying never stopped.

When Chicago started recording their sixth album at Guercio’s Caribou Ranch studio in the Rocky Mountains, their drug use escalated. “That’s when the drugs got heavier and things got weirder,” says Seraphine. “There was cocaine everywhere.”

Meanwhile Back At The Ranch, a 1974 US TV special, showed the band and their partners at the Colorado studio. In one scene, Kath is seen racing his motorcycle around the mountains. But with their spaced-out grins and thousand-yard stares, most of the group, especially Kath, look like they’ve been awake for days.

“Terry could handle more drugs than any human being I have ever met. Way more than the normal bear,” says Loughnane. “But it was killing him.”

Unfortunately, Kath had acquired another dangerous hobby: guns. “He collected guns and started taking them everywhere,” says Seraphine. “And guns and drugs are a bad combination.”

The Number One albums kept coming, but there was now a conflict between those who preferred Chicago’s jazz-orientated style (Seraphine, Kath) and those who wanted shorter songs that would get played on the radio (Guercio and Cetera). Perversely, the song that re-branded Chicago as a radio-friendly pop act very nearly didn’t make it on to 1976’s Chicago X. Cetera’s string-laden ballad If You Leave Me Now was added at the last minute on Guercio’s insistence.

Naturally, Loughnane, who still plays the song most nights on tour, is reluctant to bite the hand that feeds. “You can’t deny its success. Number One all over the world and it still works today.”

If You Leave Me Now was a fine pop song, but it didn’t sound like Chicago and it didn’t feature Terry Kath, who excused himself from the recording to ride his motorcycle.

By now, however, Kath’s drug use was becoming a serious issue. “He was incredibly unhappy and depressed,” revealed Jimmy Pankow, “and doing drugs on top of that compounded the situation.”

Furthermore, Kath’s obsession with guns scared his bandmates. In his Beach Boys biography, The Eyes That Smiled, writer Paul Mendoza recalls an incident in which Beach Boy Carl Wilson was partying with Chicago and saw Terry playing Russian Roulette, panicked and knocked the gun from his hand: “And Terry punched Carl in the face, knocking him down,” forcing Robert Lamm and others to restrain him.

On his last night alive, January 23, 1978, Terry Kath ended up at Chicago roadie Don Johnson’s apartment in Canoga Park, California. Johnson was one of Kath’s regular drug buddies and, according to Seraphine, “Terry had been on cocaine for a couple of days.”

Johnson, the only witness to Kath’s death, told the band what happened. According to him, Kath brought his guns into the apartment and began cleaning a 9mm semi-automatic pistol at the kitchen table. Johnson warned him to be careful. Terry showed him the gun’s clip in his hand. Without the clip, the pistol wouldn’t fire.

Kath then put the clip back into the gun and began waving it around, believing the chamber was empty. “What do you think I’m gonna do?” he’s supposed to have said. “Blow my brains out?” Unknown to Kath, though, there was a single bullet in the gun. According to Johnson, the guitarist waved the revolver near his temple, with his finger on the trigger, and accidentally released the round. He died instantly.

Danny Seraphine remembers learning of Kath’s death in a call on his newfangled car phone. He drove straight to Johnson’s apartment, to find the roadie sobbing in the corner.

“Terry’s lifeless body was sat back on the couch, his head angled towards the ceiling,” he recalled. “Two steps forward revealed a bullet hole in the side of his head. His eyes were wide open, staring off blankly into the distance.”

The drummer was still there when the police arrived. The coroner struggled to lift Terry’s body and asked Seraphine to help. He refused. The guitarist was too tall to fit in the body bag, and Kath’s corpse was carried out of the building with his size 12 snakeskin boots sticking out of the end.

Rumours of suicide circulated, but everyone in the Chicago camp disputes this. “It was a stupid accident,” sighs Lee Loughnane. “I had to touch his body at the funeral, to realise that it was just a shell, that Terry had gone.”

The band talked about splitting up, then decided against it. But carrying on was one thing; coping with Kath’s death quite another.

Terry’s replacement was former Crosby, Stills & Nash sideman Donnie Dacus. He lasted two albums. “Donnie looked like Peter Frampton, he had the image…” says Seraphine. His voice trails off. “We were still reeling from Terry’s death, and there were still drugs in the band.”

“It took me two more years to clean up,” admits Loughnane today. “I’ve now been sober thirty “seven years.”

There have been further line-up changes over those years. Cetera quit in 1985, Seraphine was fired in 1990 (“That hurt,” he says flatly) and Keith Howland has been Chicago’s guitarist since ’95.

Ultimately, there are two Chicagos: the one with Terry Kath and the one without. And the one without scored some huge hits in the 80s, including the Peter Cetera ballads Hard To Say I’m Sorry and You’re The Inspiration. “When we started, we thought we could get away with anything musically,” sighs Loughnane. “And we had to learn that you can’t. There will always be a compromise.”

In the end, perhaps, Terry Kath wasn’t one for compromise, and ultimately, it cost him his life. “Making this documentary, I’ve learned that my dad was a complex guy,” admits Michelle Sinclair. “But part of doing this film is to let people who’ve lost someone because of drugs know they’re not alone.”

The Chicago of 2015 are clean, sober and slicker, and still playing over 100 shows a year. They still do some of the old songs. But, inevitably, it’s different. “It’s not the same band,” says Lee Loughnane. After all, how could it be? “But Terry Kath is still in the music. His legacy is in everything Chicago does.”

Perhaps the big man with the loud whistle and the even louder guitar sound isn’t going to be forgotten after all.

For more information about Searching For Terry, see www.terrykath.com