It’s February 1967, and the 13th Floor Elevators are primed for the biggest night of their lives. The newly built Houston Music Hall Theatre is rammed to the rafters. The record company bigshots are here, as are a bank of engineers with recording gear, ready to cut a live album

But it’s apparent that things are not going well. The cops are out in force, due largely to the Elevators’ reputation as drug freaks. Paranoia has crept in, and the band are nervous. Before they hit the stage, guitarist Stacy Sutherland drops a tab of Sandoz acid. As it kicks in, bandmates Roky Erickson and Tommy Hall start turning into wolves before his eyes. Then, as Sutherland recalls later, he’s visited by angels who tell him he’s going to die…¶

The gig is a disaster. Sutherland was there in body only. Erickson was fuggy himself, a mixture of anxiety and LSD. The live album is scrapped, and the Elevators lose momentum. Instead of going out on a nationwide tour, they are reduced to a life of cultdom on the Texan club circuit.

The gig was the embodiment of the 13th Floor Elevators’ career. They were the first, and arguably the greatest, psychedelic rock band of their era. They had the songs, the attitude and the talent. But it went wrong very quickly, blighted by bad luck, bad choices and very real madness.

The Elevators’ influence has been acknowledged by Led Zeppelin, Josh Homme and Patti Smith. ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons once declared that Erickson “is one of the out-and-out wildest rock singers. And the 13th Floor Elevators are the quintessential psychedelic guys”.

It started brightly enough. Formed in Austin in 1965, the Elevators comprised Erickson, fresh from local group The Spades, and ex-Lingsmen Stacy Sutherland, Benny Thurman and John Ike Walton. The central figure in shaping their vision was Hall. A non-musician, he’d studied chemical engineering and psychology, and was convinced that LSD was a gateway to spiritual evolution. He duly urged the band to ingest as much as possible.

The Elevators scored a regional hit in early ’66, with You’re Gonna Miss Me, a brutal proto-punk anthem written by Erickson. By October the single had crashed into the Billboard chart. The following month saw the release of debut album, The Psychedelic Sounds Of The 13th Floor Elevators. Fuelled by Erickson’s extraordinary yelp and the lysergic gurgle of Hall’s electric jug, they sounded like no other band, before or since.

Unlike most of their guitar-driven peers, they weren’t interested in rebellion for rebellion’s sake. The Elevators made music for seekers, lashing their splenetic rock to mystical philosophy. According to lyricist Hall, the correct amounts of acid, mescaline, magic mushrooms and music could take you to the pyramid of enlightenment. Their best songs – Roller Coaster, Fire Engine, Reverberation (Doubt) – were as startling as they were fabulous.

After touring California with Quicksilver Messenger Service in early ’67, the Elevators were set for a breakthrough. But the album failed to make the charts. Their label, International Artists, began to panic, prompting them to organise the disastrous Houston show. By the time the band began recording a second LP, _Easter _Everywhere, they were falling apart. There had already been drug busts, now there were various legal wrangles to contend with.

When it was eventually released in November, Easter Everywhere sounded like the label’s investment had paid off. The Elevators were still primarily a jugged-up guitar band, though now there was added textural detail and a wider remit that found room for folk and Eastern influences.

Alas Easter Everywhere sold even less than its predecessor and by April ’68 the Elevators had played their last gig. Their demise was accelerated by the increasingly erratic behaviour of Erickson. His contributions to a final album, 1969’s Bull Of The Woods, was minimal.

It was all over before then anyway. Busted for marijuana that year, Erickson pleaded insanity to escape a jail term. He was sent to a mental hospital instead. He eventually ended up at Rusk Prison For The Criminally Insane. Sutherland also found himself in prison, on heroin charges, although he returned to music in the 70s. Tragically he was accidentally shot dead by his wife in August 1978 following a drunken row. Hall, meanwhile, discovered Scientology and moved to San Francisco.

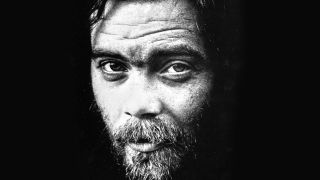

Erickson attempted a solo career in the early 80s, but the years of incarceration had left him with severe problems. The demons he howled about on lurid songs like Two Headed Dog and Creature With The Atom Brain seemed way too vivid. He’s since gradually returned to playing in public, having been afforded psychological treatment under the custody of his brother, Sumner. But Erickson has no regrets.

“I just enjoyed all my stuff,” he tells Classic Rock. “I’ve been real particular about it because it’s been a choice to make. Would I do anything differently if I had my time over again? I think I would do the very same things.”

What happened to the 13th Floor Elevators is a cautionary tale for anyone in a band. Roky Erickson sold his soul for rock’n’roll and only just survived. But it is also a testament to a bunch of individuals who dared take music to its outer reaches, to bring meaning to chaos. As such, their legacy is immense.