We’re in the upstairs lounge of the reassuringly old school boozer on that squally, rainy Thursday in a post-New Year London. The 2012 Prog Awards Visionary Peter Hammill has been speaking at length about his new solo album

…all that might have been… and his one-time alter-ego Rikki Nadir (see Prog 53). Now the conversation turns to the new Van der Graaf Generator live album, Merlin Atmos, while Hammill also looks back on the heady 18-month period in 1977⁄78 when VdGG became Van der Graaf.

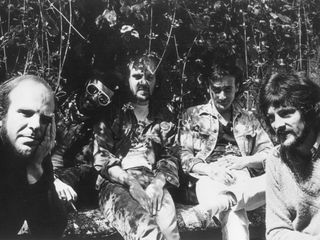

At the end of 1976, after three albums in a remarkable two years since they had reunited, Van der Graaf Generator were making some of the best music of their career. However, they were increasingly tired, and almost definitely broke. Keyboard player Hugh Banton, whose organ playing had been so central to their live and recorded work, had recently married and felt the calling to get a ‘proper’ job. He left the band after fulfilling his commitments, but there were still dates booked and albums owing. Remaining members Peter Hammill, Guy Evans and David Jackson had to move fast. “In the words of Mark E. Smith,” Hammill laughs, “we were a working band, so what do we do? We tour, we make records.”

The gap had to be filled, but Hammill being Hammill, the easy route for a straight replacement was not an option: “Van der Graaf came about because Hugh had left,” Hammill states.

He asked violinist Graham Smith to join. Smith was from Charisma labelmates String Driven Thing, who had played on Hammill’s yet-to-be-released solo album, Over. “We’d known Graham and we didn’t want any keyboard player to come in as a replacement,” Hammill says. “We felt that the best route would be to have Graham involved.”

Hammill also called on old friend and ex-colleague Nic Potter to play bass, something Banton had been playing on pedals for the past four albums – ever since, in fact, Potter had left the group in 1970. Potter, too, had played on Over. “At first, it was going to be just Graham coming in and we’d be a five-piece – we’d have violins with horns, rather than keyboard with horns. I think we rehearsed a day or so, at which point David decided to leave.”

Jackson’s sax had been similarly integral to VdGG as Banton’s organ, but again he was faced with the dilemma of raising a young family on next to nothing and, missing his old comrade, he too left.

“It was the usual madness of VdGG at all stages. By that time, the tours were booked, there were only so many days to go and we were suddenly a four-piece,” Hammill sighs.

It led to a fundamental shift in the group’s sound. “Violin is a great soloing instrument and can be structural, but not as structural as keyboards or horns,” he says. “I had to step up and play more guitar, and Nic more forceful bass. Simply by the cards we’d been dealt, we ended up being the group we were, which was very, very aggressive and very good fun, but quite a surprise to us as well.

“We said we were continuing and would still do these dates,” Hammill continues. “These days everything takes months to sort out; then it was literally just a matter of days. We toured a bit and recorded almost straight away – things happened very, very quickly, which was great. In turn, it all fed into the writing of The Quiet Zone/The Pleasure Dome. A lot of it was written once we’d established what sort of group we were. Some of the writing was expressing the headlong rush that we were involved in. In a way, it was very much an autobiographical record. Not of me personally, but the group, as it was constituted in those days.”

With the line-up shift and newfound unfussiness, the band sheared the ‘Generator’ from their name, becoming simply Van der Graaf. A tranche of European dates, some supporting Hawkwind, honed the group’s sound. “Any trimmings had gone. We were pretty fierce and direct, because a lot of the tunes we were playing from The Quiet Zone/The Pleasure Dome are generally not that complicated, but they are pretty forceful, plenty of distortion – embellished three-chord tricks, if you like. We were pretty ferocious.”

The sound they were creating chimed perfectly with the mood of the year, with punk seemingly sweeping away the old guard. Hammill and Van der Graaf received the ultimate accolade – being praised by the Pink Floyd-hating Johnny Rotten/Lydon at the very apex of the punk wars.

Recorded between May and June, The Quiet Zone/The Pleasure Dome was released in early September 1977. It remains one of the most aggressive and accessible records Hammill has ever put his name to. With its memorable picture of the band on the reverse (which they had shot to be the cover) and the Charisma-commissioned painting by Jess Artem of a trapeze artist high above the world on the front, along with John Pasche’s newly designed group logo, the album felt relevant and contemporary. NME and Sounds both reviewed it warmly.

Hammill gives a lot of the credit for the new sound on the album to bassist Potter. “A lot of it was hung on the bass. Mo [Hammill’s name for Potter was ‘Mozart’] invented a whole different way of playing bass in terms of flanging and overload. He and Guy are one of the great unsung rhythm sections – capable of great sensitivity, but also great overload if required.”

To support the album, the band toured the UK, playing throughout October and November. They had convened at Headley Grange, where Led Zeppelin and Genesis had recorded, to rehearse. Former cello teacher Charles Dickie joined to make the group a quintet, responding to the marvellously worded Melody Maker ad: “Cellist/keyboard player required for a bizarre and demanding post in a named organisation.” The five-piece band toured a selection of recent material, Hammill solo work and two songs never played live by VdGG: Pioneers Over C and a generous helping (though not all) of A Plague Of Lighthouse Keepers.

It was decided to capture the intensity of this live group on vinyl, for the first live album in VdG(G)’s career. The Marquee in London was booked for two dates in January 1978, with the second night being captured, warts and all. No overdubs were to be employed. The resulting album, Vital, is one of the most direct double-lives of the period.

“Vital was very, very fierce,” Hammill states. “We were held together by Sellotape and sealing wax. As ever, we were on the verge of going bust. We knew our days were numbered in terms of getting advances for making albums. The core of Vital is the fury of the Quiet Zone band, as well as David Jackson returning as our special guest.

“The recording was pretty wild, and Guy [Evans] mixed it. He took all the tapes away to find out what on earth we had managed to record. He did a great job of making it sound like it sounded.”

It was all coming to an end. The group played the Marquee again in June 1978, which was attended by John Lydon, as well as Hugh Banton. “We didn’t know it was over; nobody knew,” Hammill says. “We still did a few shows after Vital. We were playing for our lives.”

A spot on the bill at the Kohfidisch Festival on June 17, which was filmed, proved to be the band’s final gig. Van der Graaf split in July 1978, just as Charisma pronounced Vital to be their biggest-selling album to date. The double album’s special price and Lydon’s patronage certainly helped to boost sales.

A statement from the band read: “Our decision is unanimous, unreserved and brotherly. There are no differences or antagonisms between us. But the band, the name, this phase of the story all end here.”

Fortunately, we know that it didn’t end there for Van der Graaf Generator, but it did for VdG, although their spirit could most definitely be seen (as well as three of its members) in Hammill’s 80s outfit, the K Group. With the untimely death of Nic Potter in 2013, any hopes of the VdG version of the group reuniting were thwarted.

“I don’t think there are many bass players like Mo,” Hammill says. “It would be a very different thing. Never say never, but I was a younger man with more resources in those days.”

The two albums that bear Van der Graaf’s name offer a glimpse into something very different indeed, and they also generated an all-time Hammill classic in The Sphinx In The Face. “I still play it occasionally; it is very good fun. It’s a little bit too guitar-based to play now in VdGG, as currently constituted, as we are in slightly different territory.”

Hammill looks back at the period with great affection. “Maybe today’s trio takes more mental energy,” he says, “but the VdG stuff was very physically demanding to perform.”

Peter Hammill discusses Merlin Atmos – Live Performances 2013, Van der Graaf Generator’s third live album of their 45-year career.

One of the most pleasing occurrences of the 21st century has been the “reunion not reformation” of Van der Graaf Generator. Getting together again in 2004 after meeting a few too many times at funerals for friends and associates, the group became a trio in 2006 with the departure of David Jackson. Still a going concern in 2015, VdGG have now been together longer this time than all of the original incarnations of the group put together. “We enjoy being in each other’s company,” Hammill says. “And doing it in one-month bursts makes it a lot easier as we are not on each other’s backs.”

A live album, Real Time, was released in 2007 to capture the four-piece version of VdGG’s return, and now it’s joined by Merlin Atmos, which captures the full force of the band. “The new live album was responding to what we’d done as a trio. Every time we’ve toured, it’s been for a reason – new songs to play live, old songs to evaluate. On every record, we’ve set out to do something different here in one way or another, so there’s always a reason, which has been crucial to everything in VdGG’s history.

“We’d done Trisector, A Grounding In Numbers and Alt, which showed we hadn’t lost that edge of madness,” says Hammill, evaluating the career to date of the Banton-Evans-Hammill line-up. “The story of Merlin Atmos is our commitment to doing long-forms. They had always been part of the old VdGG back in the 70s, but hadn’t come close to it so much in modern times.”

The group decided to play some shows in 2013 that highlighted two fabled, lengthy pieces. “So we did Flight, which was originally from my solo album A Black Box,” Hammill says. “Having done that, A Plague Of Lighthouse Keepers came up, which was only ever played live once or twice back in the day. If we did it, could it be interesting, could it be convincing?”

When announcing the 14-date European tour, the group revealed in advance that they would be playing Flight and Lighthouse Keepers. “We said that before we had rehearsed together!” Hammill laughs. “That seemed like a reasonable challenge – 45 minutes; half of the show was there and the rest shifted around it. We did the tour and from our point of view, we solved all the potential problems in playing and had a great time. We recorded it, and felt it should be released, for us waving the flag for playing long-forms, or playing VdGG long-forms, which is perhaps a little bit different to most other people’s.”

There were very few shows and as ever, a small but perfectly formed worldwide VdGG audience. The album captures the set pieces, but also the relative spontaneity of some of the other material: “We didn’t know how many times we would play any of these other tunes,” says Hammill.

Importantly, the album captures the essence of a group who are still clearly at a late peak of their game. “It’s a joy to play with these guys, it really is fun,” Hammill reveals. “We are obviously more aged, but our sprightly young selves are still there in the eyes, looking across at each other. We still all love the risk aspect.”

To anyone who has seen VdGG in recent years, the intensity of their performance is still breathtaking. Their eye contact on stage and intuitive playing are unlike any other outfit. “We have to lock eyes,” Hammill says. “I better watch because they are going to do something at any given moment. That has always been the way of things – the signal signifying something is going to change is the littlest nod.”

As with Hammill’s solo career, there is nothing concrete in the diary for Van der Graaf Generator at present. “We’ve kind of reached a plateau,” he concludes. “When we came out as a trio, we had an awful lot to prove and we had to prove it, or walk away in disappointment. We’ve done that several times over. We’ve done those things and now we’re free to see whatever will emerge. We only exchanged emails yesterday, all three of us. We don’t know what will be, and that’s great.”

And with that, Peter Hammill offers Prog the warmest handshake, finishes his drink, and is off into the London air, heading back to his precious West Country.

Merlin Atmos – Live Performances 2013 is out now on Esoteric Antenna. For more information, see http://www.vandergraafgenerator.co.uk.