The sky outside is grey, central Southampton is a concrete horror, and inside the Solent University Conference Centre as its monthly record fair gets underway, first impressions are equally uninspiring. Two neon-lit adjoining white rooms house 30 tables of records and CDs, with ample room for a modest but steady flow of browsers. It’s more like a church fête than a rock’n’roll wonderland.

Soon, though, the bland surroundings become less important than the colour and feel of the records themselves: a stand of mounted Small Faces, Kinks and Badfinger singles, or that first pressing of Procul Harum’s debut LP, yours for £125. Discussions about music create a constant, warm murmur, broken by occasional blasts of rock or soul from a CD player or turntable.

There are about 50 such fairs in the UK now, the remnants of a once thriving culture that began in the mid-70s, peaked a decade later, and has survived a download-induced decline to stabilise, thanks to vinyl’s resurgence. About two-thirds of Southampton’s stalls sell vinyl. “There was a big shift to CDs in the 80s, but now selling them can be hard work,” agrees Sid Delara of USR Fairs, who promote six fairs across southern England. “It’s turned full circle. We had a 25-table fair in Bath recently, and when a customer asked me where the CDs were, I suddenly realised there wasn’t one CD in that building. As more customers are coming in for vinyl we’re on a much more secure footing, where before there was a downward spiral, and we’d stopped having several fairs.”

Over at a stall specialising in early rock’n’roll records, Barry, who perhaps wisely prefers not to give his surname, recalls how his record collecting began. “When I was in the navy, the first place I used to go when I went ashore was a record shop,” he reminisces. “Then the brothel, then the pub. That was the first time I sold a record, in ’68 in the navy. There were still record shops in Gibraltar then that had stock from 10 years previously, at 10 bob each, and I’d sell them for £2 in the ads at the back of Melody Maker, where collectors used to trade. When I started dealing records at fairs in the early 80s, Southampton’s was at the Guildhall, with a waiting list for over 100 stalls.”

Two self-described “vinyl junkies” wander over, and the intensely passionate Jason Crowle interrupts his decades-long hunt for a green-vinyl copy of David Bowie’s DJ single, to give a veteran record-buyer’s perspective. “The late 80s was a peak,” he says. “I’ve got great memories of the Horticultural Halls in Victoria, London, where people were queuing round the block to get in. You were walking sideways in the aisles, you just couldn’t move. Then by ’98, ’99, it started to go downhill big time. People started to say they could get it cheaper on the internet, and didn’t bother going to fairs.”

Crowle’s devotion to vinyl has been all-consuming. “It’s a massive part of my life,” he states. “It’s broken up a few relationships. We’re collectors, we don’t sell. I like all sorts of genres: freakbeat, psychedelia, prog rock, modern jazz, funk. It’s a quest, a never-ending road. I’ve been collecting since ’74, when I was a kiddie. I’ve got six rooms full of records, with very big archives of The Beatles, David Bowie, the Stones, Who, Kinks, Small Faces, Marc Bolan. Once you start collecting something, you want to really collect it. It’s the thrill of the find, and actually meeting people and conversing about music. I can’t stand the internet. I hate the computer. To me it’s a soulless thing. When I started going to fairs in Southampton in 1979, people were talking about what great albums Hunky Dory, Electric Warrior or the White album were. Nowadays, a lot of people talk about how much something went for on eBay. It’s not about the love of music any more; it’s about the love of money. I play my records. Even when I found an acetate of The Beatles’ Can’t Buy Me Love in a car-boot sale three years ago for £2, I played it.”

Crowle reluctantly began to collect CDs when the lure of their extra tracks and special editions became impossible to resist. But his love for vinyl stayed true. “CDs are convenient,” he admits. “When you come in after a few beers, you’re not going to whack a record on. You can ruin a lot of rare vinyl that way, when you wake up in the morning and go, ‘Shit, what did I do last night?’ But vinyl’s in my blood. It’s always been king, and always will be.” Record fairs will always beat eBay for him, too. “The thrill of the hunt’s not there when you get it through the post. Plus you might be disappointed when you see the condition. I want to see it, handle it, converse with somebody and do a deal. And talk about music, that’s the most important thing. I’ll always turn up to record fairs.”

Though some dealers make a full-time living, others are continuing their own vinyl obsession. Marcin Czerniawski, the youngest dealer in Southampton today, is also the only Pole. “The reason I took my family to live in England two years ago is actually records,” he says. “Because there are more records in England than Poland. I’m the only one who’s been crazy enough to move 2,000 miles for records. They’re my pleasure. I’m working full-time, and records are my expensive hobby.” Czerniawski stocks his stall with spares from a collection which, as his Iron Maiden T-shirt suggests, is rock all the way. He points disdainfully to an inch-thick section of Depeche Mode and Kraftwerk LPs. “Ten of those, 2,000 rock [records],” he says proudly. A £250 first mono pressing of Cream’s Disraeli Gears takes pride of place. He says he sees it as an investment.

Paul Green is a more hard-headed businessman, whose large vinyl-only stall reflects changing trends and times. It’s a recent career-swap from his previous, download-damaged life as an online DVD and CD dealer. “I enjoy vinyl,” he says, “but it’s a business to me, and I’ll always be a salesman, so I like nurturing relationships with customers. People won’t usually pay premiums for the best records at fairs now; the internet’s best for that. But a lot of youngsters are buying vinyl, so the market’s freshening from the bottom up.”

Carrie, 24, and Ese, 29, are part of that young blood. They’re among a surprisingly significant number here, many of them female, leafing through vinyl older than they are. “To be honest,” Carrie says, “I started off decorating my house with records, then a year ago I thought I should get a record player to actually play them, and be less pretentious! I’ve always been into downloading music onto my iPod and skipping through to hit tracks I already know, whereas this makes me listen to whole albums. Otherwise I’d just be watching television and not really doing anything else, whereas you can have people round with a record on and still be having a good conversation. It’s refreshing – it’s forcing me back into reality. Vinyl does sound different, too. Sometimes because my stylus isn’t working…”

Jordan, 19, also has the kind of fervour for vinyl that would make old hand Crowle misty-eyed. “Yeah, I’m a record collector,” he says. “It started when I got my first vinyl one-and-a-half years ago, Brewing Up With Billy Bragg, which my girlfriend brought back from a market. Then I stole my auntie’s record collection, and I’ve been building on that ever since. To wander round a fair all day is a fun thing for me. Vinyl’s so big, and it’s mine. CDs are so small it’s hard to be proud of it, and I can listen to MP3s, but I don’t really have it. A badge of taste? Records really are. I’ve an equal interest in punk, soul, funk and ska, because they’re so live – you can’t put on an Ed Sheeran album and expect everyone to dance around, can you? A record’s so rare, too. You can download The Damned’s first album, Damned Damned Damned, from anywhere, but finding the vinyl’s something to be proud of. And I do have the vinyl.”

These new record buyers are part of a scene that’s changing after years of stasis and decline. Fairs such as USR’s 150-table Reading event, and the bi-annual European fair Utrecht, which sprawls across the equivalent of three football pitches, are thriving. The top end of sales, notes Clive Taylor, a dealer since 1991, are still the preserve of older, wealthier fans, buying £1,000 first pressings of Floyd’s Piper At The Gates Of Dawn, or similar amounts for 70s progressive rock by obscure bands such as Dr. Z. But punk rock and 80s records are rising in price, in a generational shift. “For my first 15 years, it was people of my age at fairs – I was in my forties then,” Taylor says. “I’d go whole fairs without selling to anyone new. That’s never true today. For the rest of my lifetime, vinyl’s going to be a healthy market.”

A new generation of dealers, including Taylor’s two sons, are exploiting the internet by bulk selling to dealers in Russia and elsewhere. But old hands such as Taylor still love the record fair life. “The dealers are mostly music fanatics,” he says. “You have to be, to understand what you’re selling. We all talk about music, and our health problems. I’d get itchy feet on Saturdays if I wasn’t going to a fair.”

RARE VINYL: A few things to keep an eye out for at the next record fair you visit

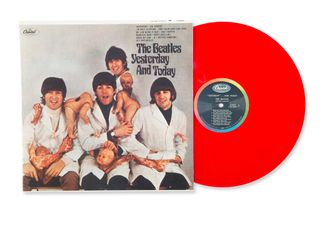

_The Beatles _

**Yesterday **

**And Today **

(Capitol, 1966)

The Fabs’ US compilation was a disaster, with 750,000 copies pressed and then recalled following outrage at the so-called ‘butcher’ cover. The music is excellent – from Drive My Car to Day Tripper – but the real reason to own the ultra-rare doll/offal edition is as a talking-point.

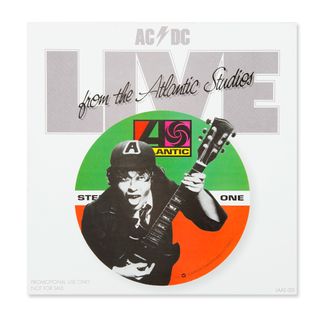

AC/DC

**Live From The Atlantic Studios **

(Atlantic, 1978)

These eight concert tracks were available only as a white-label

DJ promo or in bootlegged form until receiving a bona fide release two decades later as part of the Bonfire boxed set. That they stand toe-to-toe with the official If You Want Blood You’ve Got It says all you really need to know.

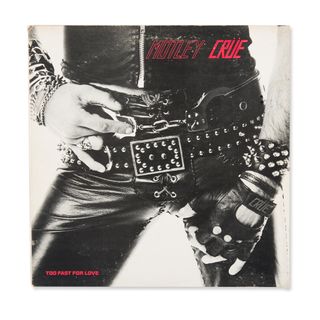

_Mötley Crüe _

**Too Fast For Love **

(Leathür, 1981)

First released on Leathür Records and memorably featuring a photo of singer Vince Neil’s leather-clad crotch on the sleeve, you don’t want to own the version that subsequently came out via Elektra. Remixed by Roy Thomas Baker, it’s an abomination compared to the red-raw vinyl original.

Rival Sons

**Before The Fire **

(Self-released, 2009)

If you came onboard with Pressure And Time, swim upstream to the Sons’ debut album. The digital reissue is the easy option, but the original platter (if you can find it) is the only way to do sonic justice to jawbreakers like Memphis Sun and Tell Me Something: songs clearly in thrall to rock’s vinyl era.

_Metallica _

**Live At Grimey’s **

(Warner Bros, 2010)

Hats off to Lars Ulrich – he’s never lost touch with his band’s vinyl-era roots. Recorded in 2008 in the basement of a Nashville record shop, the original double-ten-inch, clear vinyl version of …Grimey’s was limited to just 1500 copies (rolled out for 2010’s Record Store Day). No surprise it’s a collector’s item these days.