Oh yeah, it was the start of the summer…Late May, 1999, and Ash’s Tim Wheeler is on a swimming trip with his parents. “I had scars all over my body from slicing myself up with razor blades, and I was like: ‘This is fucking tricky. I’ll have to jump in the pool really quick and hope no one notices.’ So that was when I thought to myself: ‘I’ve got to sort this shit out.’”

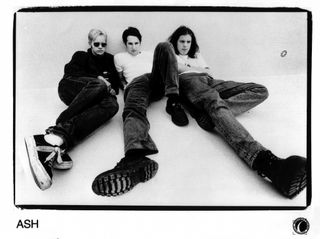

Five years earlier, Ash had crash-landed from Downpatrick, Northern Ireland into a London scene entirely obsessed with Britpop. Initially touring in their school holidays, Wheeler (guitar, vocals), Mark Hamilton (bass) and Rick McMurray (drums), proudly touted as ‘Guaranteed Real Teenagers’, soon embarked upon an unbroken run of six Top 20 hit singles, thanks to Wheeler’s casual propensity for coughing up radio-friendly seven-inch exemplars of grunge-infused perfect pop.

Their debut 1977 album had effortlessly topped the charts, but mainstream commercial success came at a heavy price. A crushing promotional workload left the band ‘psychologically damaged’. Burnt out from relentless touring, its attendant over-indulgences and the sheer weight of expectation, Ash – temporarily swelled to a quartet by the addition of second guitarist Charlotte Hatherley – set about writing and recording a ‘difficult’ second album that mirrored their inner turmoil.

In the wake of 1977’s sunny exuberance, the darkly cathartic Nu-Clear Sounds comparatively flopped, leaving Ash devastated, disillusioned and exhausted. As band morale sank to an all-time low, Wheeler simply disappeared, retreating to an anonymous New York City hotel room for the therapeutic sting of a razor blade.

“We were staring into the abyss,” he recalls, “and I thought our dream was over.”

Ash exemplify the perfect guitar-based balance of muscular rock and seductive pop. Upholding an enduring tradition for brevity, concision and sheer exhilaration personified by The Beatles in the 60s and The Buzzcocks in the 70s, Ash deal in teenage dreams that are, most assuredly, hard to beat. Tim Wheeler’s instinctive ear for melody and uncanny ability to translate deep feelings into outwardly shallow hooks allow him to create instant nostalgia. His sonic snapshot songs capture moments in time forever, effectively owning memories that they never fail to evoke, in perfect clarity, with each and every subsequent play.

Obviously, a lyrical penchant for three-hankie romanticism is all well and good, but the highway to rock’n’roll immortality is littered with the broken corpses of over-mimsy charlatans with under-cranked guitars. Ash transcend saccharine pap by hanging every pop hook on a robust backbone of steel, a fundamental attribute they’ve carried since their earliest incarnation as Vietnam, arguably (considering the 12-year old Wheeler’s voice) the planet’s least likely Iron Maiden cover band.

“When we had our first heavy metal band,” says Wheeler, “there was a guy in our local market who used to sell metal tapes and for a few months he was our guru. I played him our first demo and he said, ‘It’s pretty decent, but you’ve got to sack the singer.’”

But times were changing, and as Wheeler started listening to more alternative rock, “I realised you didn’t have to be Bruce Dickinson.”

One particular band altered embryonic Ash’s entire perception of what rock could, or indeed should, be. “Nirvana showed how to do hard rock with an emotional side,” says Hamilton. “Before them, metal was fake pap: Guns N’ Roses, hair bands, that was all we knew. When Nirvana came along it was an eye-opener, a huge moment for us. We realised we didn’t have to be overly competent, show-off musicians; it was about passion and emotion. It was like: ‘We can do this, we can be good at this.’”

I first encountered Ash – touring to promote their debut Jack Names The Planets single – at London’s Marquee Club, two days after Kurt Cobain’s suicide, and McMurray had winced in pain as I shook his hand as he came off stage: “That was the cigarette burn I’d given myself when I first heard the news of Kurt’s death. It was so weird, we’re just doing our first tour, just started releasing records and our hero topped himself. I had no idea how to deal with it.”

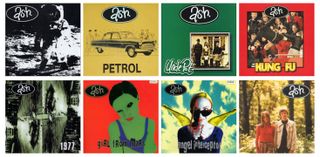

Following the independently released …Planets, Ash (newly signed to Infectious) delivered three further singles – Petrol, Uncle Pat and Kung Fu – while still studying for their ‘A’ Levels. “We kept the fact we’d got signed pretty quiet in school,” Wheeler recalls. “Nobody knew what we were up to, but I had this feeling my life would change drastically the minute I left. I knew my youth and innocence was going to come to a very sudden end and so, although under a lot of pressure to write songs and pass exams, I was really enjoying the normalcy of it. I was almost missing the peace and quiet of school before I’d even left it. It was that feeling of nostalgia that I was tapping into when I wrote Oh Yeah.”

Even discounting premature nostalgia, Ash carried canny old heads on their marketable young shoulders. They purposefully delayed recording Girl From Mars (written when Wheeler was 16) until they left school. As McMurray explains: “We knew it’d be a springboard to bigger things, so kept it back. That set things up so that once we’d left school, we’d be able to take things to the next level.”

It was almost as if the band were able to write the script for their own inevitable success, for inevitable was exactly how it seemed.

“Two days after leaving school we were at Glastonbury,” recalls Wheeler, “Two weeks later we were on Top Of The Pops with Girl From Mars. I was eighteen when we started having hits. It was great fun, and we were a good ten years younger than most of the other bands.”

When Ash arrived on the scene in the mid-90s, they represented far too saleable a commodity for anyone to pass up. ‘Guaranteed Real Teenagers’ are always at a premium in pop, and everyone wanted a slice of their fresh-faced County Down action. Consequently, as the media picked teams for the journo-concocted face-off between Britpop and Britrock, Ash (charmingly oblivious to their instinctive irresistibility to the mainstream) found themselves on both sides.

As hit (Angel Interceptor) followed hit (Goldfinger), the newly ubiquitous Ash were to be found beaming from simultaneous covers of Smash Hits, NME and Kerrang, dominating the airwaves (“We didn’t realise we were writing pop songs,” Wheeler claims, “until we started getting played on the radio”), and setting up camp on Top Of The Pops. The time really couldn’t have been more right to unleash Oh Yeah.

Arguably the quintessential Ash song, Oh Yeah is pop in excelsis, yet with all its yearning for ‘school skirts and summer blouses’, it could only comfortably be written by a teenager. Aimed squarely at the teen pop market and destined to be an ever-evocative anthem for a generation, it was ideally suited to the still-influential Top Of The Pops, and served to highlight – despite the ascending age of most emergent mid-90s bands – just how interdependent youth and pop culture were.

Meanwhile, at the eye of the hurricane, were Ash – technically, still kids. And what do kids do?

They misbehave.

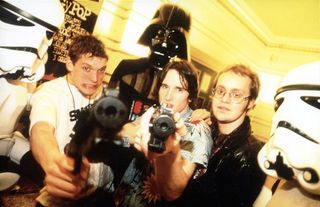

I bumped into Ash at Denmark’s Roskilde festival in ’96. Oh Yeah was high in the charts and Ash – making their way from stage to press conference – were in the process of being interviewed for Danish radio by a local journalist. It became immediately apparent that Wheeler, Hamilton and McMurray had recently enjoyed a couple of cold drinks, and each time their inquisitor turned on his recording equipment to pose his first question, the band, despite all repeated assurances to the contrary, would simply shout ‘Fuck off!’ into his microphone, wrestle him to the ground and physically drag him through a hedge. Boys, as they say, will be boys.

Ultimately, the press conference was cancelled and Wheeler thrown over his manager’s shoulder to be put to bed at 4pm. In Italy it was McMurray’s turn for the early kip. Refreshed, and finding himself in what appeared to be a tented gallery of photographs in a festival’s backstage area, the confused young percussionist simply elected to act his shoe size, rather than his age, and smashed every single one of the photos to pieces. This appalled some of the more mature onlookers, like Sepultura, who certainly didn’t approve of all the broken glass around their children.

As their success grew, Ash basically resorted to type. On leaving school they had effectively been thrown into the rock’n’roll equivalent of an apparently endless Club 18-30 gap year that involved all of the beer they could drink and absolutely none of the discipline. Wheeler, with his choirboy demeanour, got away with a certain degree of murder but he simply wasn’t capable of pursuing the level of mayhem associated with McMurray and, especially, Hamilton.

“I couldn’t keep up with Mark and Rick’s antics without having a complete nervous breakdown,” laughs Wheeler. “I definitely tried, but I just couldn’t physically do it. I used to worry about Mark, but he survived so many scrapes it seemed like he was invincible. There was always someone there to go grab his hand when he was hanging off a 30-foot balcony, shouting for help.”

Except when he fell and broke both his feet… Wheeler and McMurray simply thrust his feet into a bucket of ice and gave him more gin.

“I’ve come close to death a couple of times,” admits Hamilton, “Easily. Very close in Zurich once. I was messing around on the roof of the bus, showing off to some girls. The plan was to run from the high trailer and leap up onto the bus in front, but as I was walking backwards to take my run-up, I walked off the back off the trailer and landed on my head. Next thing, I’m in hospital with someone pulling the skin on the back of my head together to stitch it up. Our tour manager had to leap on top of me to restrain me and stop me punching the doctor.

“If I hadn’t been so drunk, the doctor said I would have tensed up and broken my neck. That was a real wake-up point for me. I mean, it’s not like I haven’t done stupid things since, but at least now I think twice before doing them.”

Of course, this was when the band were on the road. Surely this level of toxic indulgence couldn’t continue when they were off-stage?

“During the initial ‘hits’ stage when we weren’t on the road, we were probably in the studio,” Hamilton recalls. “There wasn’t a lot of downtime, it all just rolled into one. But during the times that we were in the studio, we were… probably even worse.”

1977’s producer, Owen Morris – who’d previously dragged a brace of Oasis albums kicking and screaming into the world – wasn’t exactly what you’d call a sobering influence either. We’re currently shooting the breeze in London’s RAK Studios, scene of some of the band and their producer’s more notorious exploits.

“Ah yes,” grins McMurray, his eyes suddenly ablaze and widening in the general direction of mania, “The guns and Lemsip phase.”

“The worst times were when we were in residential studios,” shudders Wheeler, a man who it increasingly transpires could probably be best described as ‘long-suffering’. “We spent a lot of time at Rockfield in Wales and El Cortijo in Spain. I remember leaving there one weekend, expecting you guys to do a bunch of work, maybe some bass stuff. When I got back to Spain at the end of the week, they’d done nothing except…”

“… shot your guitar,” beams McMurray.

“Yeah,” Wheeler deadpans. “Owen and Mark had a BB gun in the studio and were putting pellets in my 1961 Les Paul.”

They also destroyed the studio owner’s priceless pomegranate tree. “He was a hippie,” Hamilton explains, “so he was absolutely furious.”

“Then Owen was trying to shoot cocaine up his nose with an air pistol,” offers Wheeler. “It just went everywhere…”

“…And,” concludes McMurray, “he pretty much blew his nose out.”

Were there no authority figures administering any kind of discipline?

Hamilton: “If someone was to tell us not to do something, it was pretty much the green light to do it twice as fucking bad. If anyone tried to intervene, we… Well, we wouldn’t like it.”

Wheeler: “We were lucky none of us got crazy coke habits.”

McMurray: “Because of that ten-year gap in our ages, everybody else needed drugs just to keep up with us because we were three teenage kids on a booze rampage.”

Hamilton: “Literally everybody around us was off their faces on coke. They were all acting like assholes and we were like, ‘Okay, we can do whatever we want, but we’re not going to be like that’.”

McMurray: “So we just drank booze instead. Which is probably why we’re still here.”

So how did we get from three lads, riding high on a coke-fattened Britpop hog, drinking themselves insensible and generally cocking about the place in a proto-McBusted orgy of delirious, consequence-free misbehaviour, to Wheeler, staring into the abyss, in his swimming trunks? Obviously, no one embarks on the kind of highly pressured binge that the impractically extensive 1977 tour turned out to be without suffering the most debilitating hangover. Ash left the road in bits, psychologically and physically… Put a fork in their arse, they were done.

Initially, it was decided to recruit former Nightnurse guitarist Charlotte Hatherley (above, second left) to take some pressure off Wheeler. It was an arrangement that lasted for three albums, incorporating some of the band’s finest work, concluding with Hatherley’s 2006 departure when the core trio elected to strip back to their original incarnation. Ultimately, adding an extra guitarist to the ’97 Ash line-up was rather less effective than applying a corn plaster to a decapitation. The band’s problems were deep-seated and potentially terminal.

Like their hero Kurt Cobain, on attaining a fame they neither expected nor particularly sought, they found that it wasn’t to their taste. So they deliberately shied away from the commercial material that had served them so spectacularly on 1977 and guess what? It didn’t sell.

“We were trying to become more of a serious album band,” admits Wheeler, who also suffered a degree of writer’s block during the sessions.

“There are some great songs on there,” says Hamilton, “but we needed to realise that just because something’s artistically pleasing for yourself doesn’t mean it’s going to be successful.”

Snatching defeat from the jaws of victory was a conscious decision the disillusioned band swiftly came to regret. Nu-Clear Sounds’ commercial failure took Ash perilously close to bankruptcy.

And so, following an apparent disappearance that involved an ill-conceived course of razor therapy in New York City, followed by a particularly awkward swim with the folks back home, Wheeler manned-up, took the bull by the balls and embarked upon a marathon songwriting session in pursuit of a career‑saving masterpiece.

“We thought our dream was over,” he says, “so we were very fucking determined for that not to be the case. I took a year out and spent a lot of time at my folks’ house writing songs. We knew we needed to write a couple of hits to come back. The focus was: ‘We’ve built ourselves on singles so we need some more hits.’”

Eventually, Wheeler delivered Shining Light – a career-saving love song written for his then girlfriend, Audrey – that the band immediately recognised as a hit. Incredibly, Infectious weren’t so sure. With the label voicing reservations concerning Shining Light’s hit potential and reluctant to allow Owen Morris anywhere near the band, Ash decided to bankroll a Morris-produced demo session themselves. On hearing the results, Infectious could only admit defeat.

As Ash reconvened with Owen Morris to record their third Free All Angels album, and its all-important Shining Light lead single, McMurray recalls that, maybe for the first time, they were fully on top of their game. “After Nu-Clear Sounds stalled, it felt like everything could be slipping away. That focused us for Free All Angels. There was a sense that: ‘If this is going to be our last album, let’s make it our best.’”

The band’s conscientiousness paid rich dividends as Free All Angels’ three million sales took Ash back to the top of the album charts. Shining Light went Top 10 and earned Tim Wheeler an Ivor Novello Award for 2001’s Best Contemporary Song.

In retrospect, it seems Shining Light was the life-affirming mega-hit Ash needed, not only to save them from ruin in the short term, but also to fall back on in the future. Without the staggering sales the song generated for Free All Angels, Ash could never have felt secure enough to risk replicating the potentially suicidal artistic volte-face of Nu-Clear Sounds by heading off to America to record the metal-influenced Meltdown album with Foo Fighters’ producer Nick Raskulinecz – perhaps to placate their inner Vietnam.

This time their risk paid off – Meltdown went Top 5, and the band felt confident enough to strip back down to a three-piece for the self-produced Twilight Of The Innocents. The final album of their major-label deal was essentially the sound of a band pleasing themselves and, with lackadaisical record company support, it performed another commercial bellyflop.

By now the three members of Ash were far better equipped, both financially and emotionally, to deal with a dip in popularity. Financially buoyant since Free All Angels, Wheeler and Hamilton relocated to the United States on completion of the Meltdown tour, to become near neighbours in New York and New Jersey respectively. “There was a great freedom in being in America,” says Wheeler of his decision to up sticks from London. “It’s nice to go about your daily life unrecognised. In New York they don’t give a fuck who you are.”

Hamilton met his now wife at the final New York show of the tour: “I mailed my keys back to the agent in London and told him: ‘Sell it.’”

McMurray, meanwhile, resettled in Edinburgh. Mindful of the work-related stress that had impaired his banker father’s every waking moment, he considered it prudent to maintain a safe distance between himself and ‘the firm’. Three thousand miles seemed about right.

Disillusioned by the album-tour-album treadmill associated with a major-label deal, the newly independent band decided to inflict an even more rigorous release schedule upon themselves. The so-called A-Z series involved the delivery of 26 alphabetical singles, released at two-week intervals over the course of a year. Newly settled in the most multicultural of cities, bombarded by a broad range of diverse club-land influences, from 80s new wave to contemporary jazz, and freshly ensconced in their very own Atomic Heart recording studio, Ash set to work.

Obviously, the dream outcome for A-Z would have been that, taken as a single body of work, the series would have comprised 13 Oh Yeahs, 13 Shining Lights, 25 Girls From Mars and a token Sick Party. But despite trying to transcend the tired old album dynamic, when ultimately compiled on a pair of CDs, the As-Zs sounded a lot like a couple of, well… albums: a fair few choice cuts, some experimental eyebrow-raisers and one or two to file under ‘ho-hum, collectors only’.

It was a huge undertaking, and despite not generating quite the sales expected or igniting a 21st-century pop chart long since oblivious to the once irresistible charms of guitar bands, it was considered to be an artistic triumph by an Ash no longer driven by chart positions or the pursuit of filthy lucre. “The stuff we were most proud of,” says Wheeler, “was that which broke new ground for us.”

The Ash that recorded the A-Z series were three massively different individuals to the carefree, booze-fuelled, guaranteed real teenagers that had careened out of Northern Ireland in 1994. Wheeler had long since set aside the razor blade. Hamilton and McMurray had both become fathers, and along with fresh responsibilities came different priorities. All concerned had dried out.

While the drink, the overwork and the pressure had previously taken Wheeler to the very brink of collapse, obsessively self-harming while staring into a post-Nu‑Clear Sounds abyss, Hamilton and McMurray had both stared into the face of breakdowns of their own.

“I had a period where things weren’t happening… mentally,” Hamilton admits, choosing his words carefully as we chat one-to-one over a significantly soft drink. “I don’t like dwelling in the past but that wasn’t such a good point. Being that paranoid, anxious, bipolar or whatever you want to call it, is horrible. Having some sense of being in control is nice. We were out of control for ages. If anyone tried to intervene we’d just get worse because that’s what we were like.

“Coming from an Irish/British culture where you live for the weekend, then go out and get fucking destroyed, spend the week recovering while doing a crappy job, then do it again, you’ve got that mentality already. Then when you’re 15 and you find yourself in a position where you can do it every day, people are encouraging you to do it, and guess what? It’s free. At some point it’s going to take its toll.”

McMurray’s Damascene moment coincided with the occasion he drank so much that he forgot how to play drums. “It was a pretty big deal for me. We were doing a morning soundcheck for an XFM session prior to playing Guilfest and for two hours my brain just shut down. By the time we got to the session, my brain knew what to do but my body wouldn’t do it. It was weird because I was in this little booth by myself, I could see the other guys through the glass, and it was painfully obvious from the look on their faces that I couldn’t play. With a festival to do that night, everyone was freaking out. So it really got to me; it was almost nervous breakdown territory.”

After A-Z, Ash embarked upon a three-year hiatus, during the course of which all three took care of their families. Hamilton and McMurray both became full‑time dads, watching their six-year-old daughters grow while both adding a further baby to their stroller‑pushing workload. Wheeler, meanwhile, having lost his father to Alzheimer’s, recorded his first solo album, Lost Domain, a powerful emotional response to his father’s death.

Clean, refreshed and with business taken care of, Ash reconvened last year to record their sixth album. Entitled Kablammo! it’s a return to the classic Ash formula: the effusive and strident pop-core of 1977, a couple of heart-swelling hackle-raisers and the barest minimum of experimentation – or, as Wheeler describes it: “A fun pop record with a few ballads. Whatever we decide to do next can go wherever it wants to go, but once in a while it’s good to just play to your strengths.” Amen to that.

Ash may still be able to concoct perfectly crafted McCartney-standard Beatles-era guitar pop, but in an era where the mainstream commercial pop landscape is dominated by female-fronted electronic dance music, expectations within the band have diminished. It’d be way more tragic if the band hadn’t made hay while the 90s Britpop sun had shone, a time when TOTP-driven markets were bull markets and hits were hits; a quirk of chronology that’s left Ash more than capable of living on their heyday residuals.

As it is, Wheeler can at least afford to be gracious in defeat. “We were lucky that guitar pop could still top the charts and be really celebrated in the 90s, but it’s a shame that it, well… just went out of fashion, I guess.”

Then again, the Ash that I encountered back at the Charing Cross Road Marquee never expected the slightest sniff of mainstream success. A Top Of The Pops appearance was as much a dream then as it is a memory now. “Although we were dragged into the pop world, that was never our initial intention,” says Hamilton. “We were just metal kids.”

“We didn’t really pay attention to the charts until we were in them,” admits McMurray. “Then, once we were, people in the business became very concerned that we stay there, and then, before we knew it, a lot of the pressure was coming from ourselves.”

Of course, two decades later, Ash have outlasted and outperformed all those Britpop/Britrock also-rans that various branches of the pop, indie and rock media contrived to place them into direct competition with: Feeder, Supergrass, Reef, Terrorvision… So what is the ultimate secret of Ash’s extraordinary longevity?

“The reason we’re still here is because we chose booze over coke,” says Wheeler. “We also had significant failures early on, so we’re not scared of that. After Nu-Clear Sounds, we managed to work hard and bounce back, and that gave us real resilience. Failure’s a very important part of success – it’s when you learn the most about yourselves and the depth of your commitment.”

“It’s very easy for people who have a lot of success to get inflated egos,” adds Hamilton. “But because we’re all school friends and have known each other since the age of eleven, it’s a grounding force. It’s not like all of a sudden anyone can just change into a different person, flex their ego and get away with it. We’ve known each other too long.”

“And as for Britpop,” McMurray smiles, “although we were at the party, we never really belonged there.”

“Yeah,” Wheeler laughs. “We were just the kids who snuck in the back and drank all the booze.”

Ultimately though, Ash endure because despite the prevailing tyranny of genre apartheid, there’s still no finer sound than when rock and pop collide in perfect harmony. That and the fact that even at 38, Tim Wheeler still sounds like a keening teenager in unrequited lust.

Oh yeah.