There’s something reliable and unchanging about Genesis keyboard player Tony Banks. He’s like the keeper of the Genesis flame. Banks may have co-written such stadium pop hits as Turn It On Again and Invisible Touch, but you suspect he’s the one band member who’d throw in some extra arpeggios or a five-minute piano solo given half a chance. “I like our hits… but I did love Genesis’s prog era,” he admits.

A Chord Too Far is a four-disc box set of Banks’s solo work that covers all bases: from film soundtracks to prog rock, synth pop, big ballads and, most recently, classical music. And it has clearly been a labour of love. “A lot of people might not have heard this stuff before,” he shrugs. “But I’m very proud of it.”

It might surprise some Genesis fans to know you’ve made nine albums away from the band.

Let’s be frank, most of my solo work has been overlooked. That’s okay, the success I had with Genesis makes up for it. But once you’ve been through all the Genesis albums, you’ve done Mike + The Mechanics, you’ve done Phil’s [Collins], Peter’s [Gabriel] and Steve’s [Hackett] solo albums… you might find my stuff is worth a listen!

How does a Tony Banks song differ from a Mike Rutherford or Phil Collins song?

That’s where the title, A Chord Too Far, comes from. Phil and Mike used to give me a look if I’d gone too far. There’s more complexity in my songs than there is in Mike’s. I like unusual harmonies – things like the intro to Watcher Of The Skies. But I’ve written more concise songs as well. Afterglow is one of mine and that’s a very straightforward verse/chorus/verse thing.

So it’s a little simplistic to say that you do the ‘long songs’ in Genesis?

A little. I came into the business as a fan of sixties pop and Tamla Motown, and I’ve had a hand in writing the big Genesis hits. On this album, if you’re a prog rocker type, there’s a long song called An Island In The Darkness, and if you’re not, there’s Water Out Of Wine…

You’ve also recorded two classical albums (2004’s Seven, A Suite For Orchestra and 2012’s Six Pieces For Orchestra). What was it like moving into that world?

In some ways it’s a natural direction. Last year I was even commissioned to write a piece for the Cheltenham Music Festival. So, curiously, my classical stuff has gone down well, even with people in the classical world who normally hate anyone who hasn’t been to a conservatoire.

You’ve written music for several films, including Michael Winner’s The Wicked Lady. What was he like to work with?

Michael was great fun. He was actually quite self-deprecating and not as pompous as he came across. The trouble is, you can’t control the way your music is used in a film. I found I had to do everything the way other people wanted and I don’t like doing that.

It must have been hard enough doing that in Genesis.

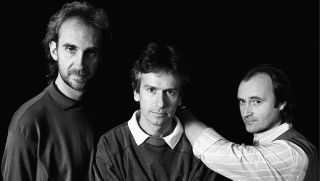

Yes. But the three of us found a way of working together. We gave each other space.

Did the band end too quickly for you?

I always thought that the Calling All Stations tour [in 1998] was an underrated escapade. But that was it. My solo albums weren’t doing much, my film music career was going nowhere, and I did think: “I’m fifty now, maybe it’s time to stop.” That’s when I wrote a piece called Black Down, and thought: “This would sound good with an orchestra…” Which led to me making classical music.

Would anything happen with Genesis again?

Mike and I would never rule anything out. But we could never do a tour like the last one [2007’s reunion tour]. As a drummer, I don’t think Phil could do it. We’ve had talks with Peter, but you can’t tie Peter down to anything.

What did you think of Mike’s autobiography, The Living Years?

I wasn’t very happy with it. He and I get on well, so I was surprised that didn’t come across. He also changed stories to make himself look better. My wife said to me: “He takes you for granted.” Which is true, because Mike and I are like an old married couple.

You’ve also been married to the same woman for ever, which is unusual in the music business.

Margaret and I married when we were making Foxtrot [1972]. We had a one-day honeymoon because I had to finish the album. The band felt sorry for me so they paid for her to come on the next tour. In fact we often had wives and girlfriends on tour. Not what some people think of as a rock’n’roll existence, but it worked for us.

Would it be fair to say you’re rock’n’roll’s least flamboyant keyboard wizard? You’ve never worn a cape on stage or played a piano upside down…

I’m not a comfortable performer, no. Thankfully we always had people like Peter and Phil who did all that. I’m a writer who’s on stage because he can play what he writes. I did wear a snorkel on stage when we played Who Dunnit [in 1981], but that’s as far as it went.

Apparently you’re a demon table tennis player, though.

Ha! When Genesis were playing big stadiums, you couldn’t go anywhere after soundcheck, so we set up a ping-pong table. Chester [Thompson, Genesis’s touring drummer] and I were about the same level. He had more style than me. I’d defend like mad but never attack.

What’s next for you?

I could see myself making another classical album. The things I’m best at in music are harmony and melody. With classical music, it’s all about harmonies and melodies… and you don’t have to worry about chords! [laughs.] I can put as many in as I like – and I do.