It’s the autumn of 1978, and the Tom Robinson Band are playing one of a pair of sold-out dates at London’s Hammersmith Odeon at the height of what their leader now describes as “our fifteen minutes of fame”. Four thousand people are singing along to the homosexual pride anthem Glad To Be Gay. But Robinson, convinced that the world “couldn’t possibly have changed that radically in twelve months”, halts the song, goes over to keyboard player Ian Parker and kisses him full on the lips.

“There was an audible intake of breath,” Robinson recalls almost four decades later. “An almost tangible shock wave of revulsion passed through many of the audience. A friend of mine was stood at the back of the hall and later told me that two beer-boys, who moments earlier had been singing along, turned to one another and said: ‘You know what? I fink these geezers are bent.’ Any maker of political pop who thinks they’re going to change the world would do well to remember incidents like that, because they’re a pretty big slap in the face.”

The notion that any gig-goer could have been unaware of what the Tom Robinson Band stood for back then is more than a little ludicrous. They bridged pub rock, punk and new wave, but weren’t really part of any of those scenes. More importantly, Robinson was one of only a handful of openly gay musicians in any genre at the time, and he was certainly the most vocal. A band ahead of their time, they railed against homophobia, racism, sexism, police brutality and social injustice. While Robinson was the only gay member, his bandmates supported his political stance – for the most part.

“We all agreed with Tom’s sentiments, but all I really wanted was to play music in a successful rock band,” guitarist and co-founder Danny Kustow says today. “Believe me, you don’t want to be in Texas playing Glad To Be Gay for five hundred cowboys who make it very plain: ‘Afterwards, we’re going to fucking kill you, man.’”

Tom Robinson always was unlikely rock star material. Born in Cambridge in 1950, his early years were spent in a council house, but by the time he reached school age his parents were wealthy enough to send him to be educated by Quakers in Essex, by way of a French boarding school. He realised he was gay in his early teens. At 16 he suffered a nervous breakdown, and attempted suicide after being spurned by another boy. At the time, in the UK homosexuality was punishable by four years in prison.

“I’d been warned to beware of queers long before realising that I was one, which left me awash with hormones and self‑loathing,” Robinson explains. “Unlike today, with Graham Norton on the TV and so many openly gay politicians, there were no role models to suggest that it was possible to be queer and have a happy life.”

He was sent to Finchden Manor in Kent, a therapeutic community for emotionally troubled boys. While he was there, two significant events would change the course of Robinson’s life. The first came on September 17, 1969, when bluesman Alexis Korner – a Finchden old boy – played an acoustic gig in the manor’s study. “Alexis came in with his guitar and sang completely without inhibitions about women, drink, policemen and civil rights, and with such normality, it was inspirational,” Robinson says.

The second turning point for Robinson came when he met Danny Kustow, who was also at Finchden. Both were budding musicians. “Tom could already write great lyrics but was still finding himself,” Kustow says now. “He showed me a few chords on the guitar; I was still a novice at the time.”

After leaving Finchden, Robinson moved to London, seeking a foothold in the music industry. His first band, the acoustic trio Café Society, were signed by Ray Davies, of The Kinks, to his boutique label Konk. But Robinson’s initial excitement fizzled out when Davies’s other commitments kept them from going into the studio. Worse was to come when Café Society’s new mentor decided to impose electric instruments on them. Robinson had already quit by the time their self-titled debut album finally got a release in 1975 (it sold a grand total of 600 copies).

Robinson’s attempt to form his own, eponymous band were hampered by bitter contractual issues; on stage the singer occasionally dedicated an ironic cover of The Kinks’ Tired Of Waiting to Davies. On one infamous night in December 1976, the subject of Robinson’s ire turned up at a gig at the Nashville Rooms pub in West London, and insults were exchanged during the show. “After we finished one of our songs, Ray shouted: ‘It’ll never be a hit!’” says Kustow, who had then just joined his old school friend in the band. “So we responded by playing The Kinks’ Set Me Free, because that’s exactly what we wanted from Ray – to be set free.”

The unseemly bickering continued for years afterwards. The TRB’s 1978 song Don’t Take No For An Answer was inspired partly by the sorry saga, while Davies fired back with his 1980 B-side Prince Of Punks: ‘Tried to be gay, but it didn’t pay/So he bought a motorbike instead.’ The rift was healed only this year, when Robinson interviewed Davies on his 6Music radio show. “I spent three hours grilling this extraordinary figure in British music about the process of songwriting,” says Robinson. “What’s the point in holding a grudge for forty years?”

The formation of the Tom Robinson Band coincided with the early stirrings of punk. Although the TRB were far from being a punk band, seeing the Sex Pistols playing live was a further epiphany for Robinson. “I hadn’t thought of myself as a lead vocalist, but seeing Johnny Rotten I realised all you needed to do was make noises with your mouth and to mean it,” he says.

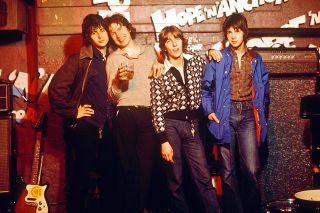

Early TRB gigs featured Robinson with a floating pool of musicians who would be taught the evening’s songs at soundcheck. It soon solidified around Robinson and Kustow, plus drummer Brian ‘Dolphin’ Taylor (who had played with a pre-fame Annie Lennox in folk-rock band Dragon’s Playground) and keyboard player Mark Ambler. The latter had auditioned as bassist, but his expertise as a Hammond player was such that they decided to add the instrument to the band, leaving singer Robinson to reluctantly double-up on bass.

From the start, tension bubbled beneath the surface. With hindsight, Robinson believes that Ambler’s musical proficiency intimidated certain other members of the band. “Sometimes the guy hardly needed to break sweat, which caused resentment with Dolphin, who really put in a lot of work,” he says. “Mark used about five per cent of his ability and still sounded incredible. So there was always friction.”

The band played everywhere that would have them, often for no money – benefits, youth clubs, schools, even prisons. In those pre-internet days they kept in close contact with their fans via a newsletter delivered for the price of a stamped-addressed envelope – an idea Robinson admits he stole from Frank Zappa.

A buzz grew up around the Tom Robinson Band thanks to coverage in the weekly music press, and record labels began to show interest. Two frontrunners for the band’s signatures were Jet – the label owned by heavyweight manager Don Arden – and EMI. The band were set to sign to Jet, but then EMI, who had passed on them a few months earlier, reconsidered. “What I’d heard of Don Arden’s reputation made EMI, whose management had just dropped the Sex Pistols, the more sensible option,” Robinson says. “And I suspect EMI’s record division signed us to make a bit of a statement.”

Characteristically, the contract was hilariously blunt. It stated simply: “We, the Tom Robinson Band agree to make you, EMI Records, a lot of fucking money. Read and agreed, the Tom Robinson Band.”

They got off to a flying start, too, with their debut single, 2-4-6-8 Motorway, a Top 5 hit in October ’77. With its roots in the gay liberation chant ‘Two, four, six, eight, gay is twice as good as straight’ it was a slyly subversive opening salvo.

But it was nothing compared to what came next.

With the band rapidly gaining a reputation as one of the best on the gig circuit, a live release was the next logical step. The four-track Rising Free EP, recorded at London’s Lyceum Theatre and sold at the same price as a regular single, gave them another Top 20 hit. Its focal point was Glad To Be Gay, a supremely catchy but incendiary anthem that made no bones about Robinson’s sexual orientation, while simultaneously decrying the homophobia and hypocrisy of the establishment.

Robinson and Kustow admit to being terrified at the prospect of performing Glad To Be Gay in such bastions of masculinity as the Bridge House pub in East London’s Canning Town or the Royal Naval Hall in Tonypandy, South Wales, but they would not be deterred. “Sometimes there were riots,” says Robinson, “but it was always an interesting experience, and for the most part people would hear it and go: ‘Good point well made.’”

The Rising Free EP was a defining statement. As well as featuring Glad To Be Gay, its sleeve included contact details for political organisations the Anti-Nazi League and the Gay Switchboard. But it brought an unforeseen problem. “When it came to do an album, we realised we’d already given away the crown jewels,” says Robinson.

Their debut album, Power In The Darkness, was recorded with producer-of-the-moment Chris Thomas, who had recently worked on the Sex Pistols’ Never Mind The Bollocks and whose CV also featured Pink Floyd and The Beatles. Despite Robinson’s reservations, Power In The Darkness was fresh, barbed and vital. The abrasiveness of opener Up Against The Wall contrasted with the slower yet equally oppressive Long Hot Summer. On Ain’t Gonna Take It, Robinson took aim venomously at ‘abortion and the gay scene/Only meant for the rich’, while Better Decide Which Side You’re On was as close to a manifesto as they got.

Sides one and two of the original vinyl LP were closed by the album’s two head-turners. One, Winter Of ’79 was a bleakly pessimistic prediction of the future, filled with imagery of petrol bombings, racial tensions and the return of national service. “To me it really felt like the world was coming to an end,” Robinson recalls. “People tend to forget the state of flux that UK society was in at the time. Just because armed anarchy on the streets of Britain didn’t come to pass, that doesn’t mean it couldn’t have happened. But it was also an exhilarating time because change was also so very possible.”

The second of those two key tracks was Power In The Darkness itself. A clever pastiche of a politician reciting a long list of ‘undesirables’ – ‘nigggers… Pakis… unionists… gypsies… Jews… pansies’, its bitter irony almost inevitably prompted controversy.

“It was satire, of course,” says Robinson. “But the *NME *actually thought we were defending the freedom of football hooligans when, of course, the song opposed the lumping together of everybody with a remotely radical viewpoint and branding them a common enemy.”

Released in June 1978, Power In The Darkness reached No.4 in the UK album chart, eventually selling more than 100,000 copies. Provocatively, it included a free stencil of the clenched fist image used on the cover of the album, the idea being that people could stencil it on to buildings and walls.

In an era when music and politics were comfortable bedfellows, the TRB were especially engaged. In April 1978 they played in front of 80,000 people at a Rock Against Racism benefit concert in London’s Victoria Park. Also on the bill were Aswad, X-Ray Spex and The Clash, although the latter’s name didn’t appear on the posters.

“They were dilly-dallying about being associated with the movement,” Robinson says of The Clash. “They also felt they should be headlining, which we had no problem with. But the ANL [Anti-Nazi League, who organised the event] wanted us to do it as we had talked about them in our interviews and featured their logo on our records. The Clash were so furious they wouldn’t come off stage. In the end our manager pulled the plug on them, which soured things a little as playing that gig was one of the highlights of my career.”

Amazingly, given the size of the target he had effectively painted on his own back, Robinson managed to avoid physical reprisals from many of the TRB’s antagonists – National Front thugs and violent homophobes. “Considering my mouthiness I was extraordinarily lucky,” he acknowledges. “But at the same time I took good care to keep myself out of dangerous situations.”

Outwardly, the TRB were unstoppable. But behind the scenes there were serious problems. Following the success of the Power In The Darkness album, EMI exerted pressure on the band for a follow-up – something they were woefully under-prepared for. Mark Ambler had left just after the debut album was finished, and Dolphin Taylor, who didn’t like the new songs, quit before they were due to go into the studio to record the second album – only to ask to rejoin soon afterwards. The answer was no.

If that wasn’t bad enough, Chris Thomas was tied up working with Wings and was unable to produce the new record. Instead, Todd Rundgren was brought in belatedly – and immediately put Robinson’s back up by insisting on choosing the songs. And while Thomas had had three months to make the first album, a mere six days had been allocated for the second.

But the biggest problem was the material. “When Dolphin told me: ‘We need some better songs,” what I heard in my stressed-out and ego-inflated paranoia was: ‘Your songs aren’t good enough,’” says Robinson. “And this from a drummer! I took it as criticism, when actually it was a statement of fact, an unpalatable truth.”

The atmosphere when the band convened in Rockfield Studios in South Wales was tense. Kustow exacted his frustration on the nearby wildlife. “I got a shotgun and shot at things off the roof,” he remembers sadly. “To me, TRB Two is just cabaret. I only like two of its songs.”

It didn’t help that the guitarist was increasingly affected by the accusation that the TRB were more about militancy than about music – something he heard a lot. “It stung me,” he admits. “I recall sitting at EMI with Tom and asking whether we could tone down the politics. His reply of: ‘No. We’ve got to be even more political’ filled me with dread.”

After the success of the band’s first album, Robinson was moving in altogether starrier circles, and his new-found status was reflected in TRB Two’s most interesting track, Bully For You, co‑written with Peter Gabriel. Another song, Never Gonna Fall In Love Again, which didn’t make the album, was a collaboration with Elton John.

“Dolphin and Danny probably wondered: ‘Why’s Tom hanging out with these megastars?’” Robinson muses now. “It wasn’t really what the TRB was about.” (Kustow dismisses such suggestions as “absolute bollocks”.)

Bully For You is the source of some contention even today. The song’s lyrical hook is the repeated line: ‘We don’t need no aggravation.’ Both Robinson and Kustow believe Pink Floyd (with whom the TRB shared both management and record label) took it as an influence when they were writing Another Brick In The Wall, specifically the line: ‘We don’t need no education.’ TRB Two was released in March 1979; Floyd’s The Wall followed nine months later.

Robinson is sanguine about the similarities. “There’s no question ‘We don’t need no aggravation’ was in the air around Roger Waters. The truth of it is that I had a really good idea for a chorus and we didn’t make the most of it. If Bully For You had started with ‘We don’t need no aggravation,’ how much better would it have been? Roger’s skills as a writer were far more developed than my own. He put a great idea to better use, so fair play to him.”

Kustow is less diplomatic. “Pink Floyd definitely ripped us off,” he fumes.

Unlike the sharp focus of the first album, TRB Two was a mixed bag lyrically. Sorry Mr Harris was a laboured spoof about the security forces in Northern Ireland, while Blue Murder lamented Liddle Towers, a boxer who died in police custody in Gateshead. But despite this – and Kustow’s concerns that activism was overshadowing the music – the album’s focus was less overtly political. But Robinson insists this wasn not a directive from EMI. “Absolutely not,” he says. “What they had wanted was Son Of Power In The Darkness. They’re a commercial organisation, and not a political one.”

Instead, Robinson was concerned that his political stance was descending into self-parody. This was complicated by the fact that there wasn’t enough of him to go round. “Letters from organisations would arrive stating: ‘Dear comrade, we note you have not written a song about… Why not?’” he says. “It stuck in the throat, but also made me feel guilty because maybe I should have done.”

There was a sense that even Robinson himself was unconvinced by TRB Two. “It doesn’t even begin to register until six or seven plays,” he told one US interviewer in 1979. Despite this, it dented the UK Top 20 in March 1979. But it was too little, too late. Within four months the band had split, finished off by a long and wearying US tour.

“Danny and I were emotionally fragile people – that’s why we’d met at Finchden Manor,” Robinson points out. “And week after week of slogging across the country, playing to audiences that didn’t really care, left us wondering why we were bothering. So we came back to Europe and decided not to.”

In the aftermath, both of them suffered mental breakdowns. A brief reunion of the TRB’s original line-up followed in 1987, and Robinson, Kustow and Mark Ambler tried again two years later, but the magic was gone. In happier times, Robinson had once described Kustow as the “living heart” of the TRB, but their relationship had become toxic.

“After the second reunion, Tom told me: ‘Danny, I’d rather gnaw my own arm off than play with you again,’” the guitarist recalls with some sadness.

“It was the single worst year of my professional life, ever,” Robinson says. “There is no amount of money that could induce me to get that band back together again.”

Since the final demise of the band that bears his name, Tom Robinson has carved out parallel careers as a solo artist and a radio broadcaster. By contrast, Kustow lives a reclusive lifestyle and no longer plays guitar. He suffers from obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), which he blames on the TRB’s break-up.

In an unexpected twist, Robinson met a woman, Sue Brearly, at a Gay Switchboard benefit show in 1987 and, as he now puts it, “found myself strongly – and inconveniently – attracted to her”. They started a family together and eventually married, prompting the ire of certain sections of the gay community, who accused him of the ultimate sell-out. Robinson addressed this in a re-recorded version of Glad To Be Gay on 1996’s Having It Both Ways album, in which he added an extra verse: ‘Well if gay liberation means freedom for all, a label is no liberation at all.’

Nearly 40 years after he founded the Tom Robinson Band, the UK is a very different place. Gay marriage is legal, and racism, sexism, police brutality and all the things Robinson railed against are, although not stamped out, at least less overt than they were in the 1970s. But he isn’t out to take any credit for that.

“Audiences change the world, not musicians,” he concludes. “Bob Geldof didn’t single‑handedly save thousands of Ethiopian lives, he made it possible for us to do so by providing a focal point. Likewise Rock Against Racism didn’t change the minds of National Front skinheads; many people were feeling uneasy about the state of race relations at the time. But of course I would like to think that we helped to fuel debate.”

MAJOR TOM

Ten essential TRB anthems.

**

**

2-4-6-8 Motorway

The TRB’s first single. U2 used to cover it as a school band. They probably didn’t know what it was about, either.

Don’t Take No For An Answer (Live)

Snotty, defiant and daubed with expletives, the opening track of the Rising Free EP was a call for disrespected minorities of many different types. It still sounds great today.

Glad To Be Gay (Live)

On Rising Free Robinson dedicates it to the World Health Organisation. He also explains that it describes a condition whose “classification to the international classification of diseases is 302.0”. Don’t say that reading Classic Rock doesn’t teach you anything.

Up Against The Wall

With its clarion call of ‘Look out, listen, can you hear it/Panic in the County Hall, Whitehall up against the wall,’ this belligerent anthem had its heaviness ramped up by 10 layers of guitars thanks to producer Chris Thomas. Trivia: Kustow actually played its solo backwards.

Too Good To Be True

Although dominated by Kustow’s glorious solo, this song was formulated around a segment written by Taylor. “I later heard a certain song on the radio and realised where Dolphin had stolen it from,” Robinson admits. “Luckily the person responsible – who is notoriously litigious – never complained”.

Long Hot Summer

Fuelled by the synchronicity between Kustow and Ambler, Long Hot Summer was based on myriad social tensions experienced the previous summer, during which the UK suffered a severe drought.

The Winter Of ‘79

‘All you kids who just sit and whine/You shoulda been there back in ’79’. Thank goodness things didn’t turn out quite as catastrophically as Robinson feared.

You Gotta Survive

With talk of looted houses, burned cities, scavenging for food and old women dying of the plague, Robinson’s post-holocaust-flavoured lyrics made Britain sound like something out of The Walking Dead, in a song that displays considerable musical sophistication.

Power In The Darkness

Robinson wore a Peter Gabriel-esque old-man’s mask when performing this song’s spoken-word diatribe, which vents against minorities of every shape and description – including you.

Bully For You

The undoubted highlight of the TRB Two album, and the song that Robinson and Kustow still believe Pink Floyd plagiarised for their own Another Brick In The Wall. Over to you, Mr Waters…

_