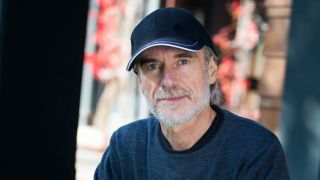

With a list of credits that includes Frank Zappa, the Mahavishnu Orchestra, Chick Corea, Stéphane Grappelli, Stanley Clarke and Elton John, Jean-Luc Ponty has racked up quite the prog-friendly CV. The virtuoso looks back over his career and forward to the next adventure.

How did this collaboration with Jon Anderson come about?

About two years ago I was asked to do a violin solo on a song that someone was producing for him. We’d already met in the 80s, so that’s how we reconnected. What was really phenomenal about this collaboration was that Jon immediately started to improvise some lyrics and melodies on a couple of my well-known pieces, like Mirage. He sent them over by email and I said: “My God, I wish we’d done that years ago!” There was a very strong musical affinity between us.

How did you feel about revisiting huge Yes favourites such as Wonderous Stories and Roundabout?

On one hand there’s that challenge – “Oh my God, these are really big hits” – but it can never be the same as before, so the goal was to make them different. I wanted to bring my own sound to these songs, without knowing in advance if it would really work. And I think it did. We hope there will be more than just this album, because we all had a lot of fun. Will there be another one? We’ll see what happens. We’re looking to play the UK and Europe next year.

In the 70s you shared a bill with Yes, in Texas, when you were with the Mahavishnu Orchestra…

I was always a Yes fan. In fact, I was a big fan of progressive bands from England: Yes, Genesis and King Crimson. I’d also met the guys from Soft Machine in London and played with Robert Wyatt, touring Germany together. So I had that connection and the music always spoke to me very strongly because a lot of it had classical roots. There was real sophistication.

I was a big fan of progressive bands from England: Yes, Genesis, King Crimson.

Are there many parallels between prog rock and jazz fusion?

Absolutely. Fusion is a wide-open field, at least in my case. It was the same with John McLaughlin. We both came from British/European cultures and had some classical tradition. In our music there was the element of jazz and improvisation and it was instrumental. That was the difference. But otherwise there was a great affinity with progressive rock. We were experimenting and using the same instrumentation and rhythms. We felt very close.

How did you get to know John McLaughlin?

I discovered him through his music. Then the first time we met was in New York, when he’d just been hired by Tony Williams, Miles Davis’ drummer. It was a shock when I heard the trio [The Tony Williams Lifetime, with Larry Young on organ]. It was so revolutionary. I went to speak to John afterwards and told him how moved I’d been by the music. Years went by and he formed the Mahavishnu Orchestra, who I opened for in the South of France. Then in ’73 Frank Zappa asked me to tour with his band, which is when I moved to Los Angeles. We did a whole tour with the Mahavishnu Orchestra supporting us. A few months later John called out of the blue and asked me to join the second version of Mahavishnu. There was no hesitation.

Having just played with Zappa, who was a rigorous bandleader, was it liberating to suddenly be with the more improvisational Mahavishnu Orchestra?

Oh yes. I loved playing in Frank’s band to begin with. When we started touring, I had many solos. But as the tour went on Frank realised that he was losing his audience with so many instrumentals. By the end I was left with one solo per night. So, as much as I respected his music, that was it for me.

Had you always wanted to be based in LA?

Not really. Musically, it was like being in heaven, meeting avant-garde musicians like Ornette Coleman and Zappa when I first got there. But I was missing my friends and French culture. Los Angeles was so different to Paris. Little by little I grew to love it, especially because the musical environment was always evolving. All the great jazz musicians – Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea, Wayne Shorter – moved to Los Angeles from New York around the same time in the early 70s. I was shy as a composer in those days, because my classical background meant that I didn’t really fit into jazz. But then there was the example of Zappa and John McLaughlin, who didn’t care about staying within the tradition of the rules of rock or jazz. They were willing to try anything that worked. So I decided to just allow my classical inspiration to come through my writing, without worrying about fitting in. I was lucky to be there at the right time.

When you started playing electric violin in jazz, at the beginning of your career, did you meet much resistance from the purists?

Oh yes, every time before I went on stage. I was playing with a symphony orchestra in Paris and coming out in my tuxedo, with my little amp in one hand and my violin in the other, and then going around the jazz clubs to jam. [Stéphane] Grappelli was famous then and the whole scene was swing and gypsy jazz, so the violin was regarded as inadequate. Sometimes they wouldn’t even let me come up on stage. But those who finally did heard me play modern jazz, in the style of John Coltrane and Miles Davis. Only then was I accepted. I’ve always been more of an instinctive player and composer. There was so much that I wanted to express, I didn’t want to have limits.

Better Late Than Never is out now on EarMUSIC. See www.andersonpontyband1.com for more information.