America is broken, perhaps beyond repair. The headlines tell you all you need to know: police shootings, gang warfare, racism, riots, murder, an unfair economy, poverty, corporate greed. Amorality has swamped humanity. The results are in, and hatred and greed won.

Neil Fallon feels this all more keenly than most of his countrymen. It is, he agrees, easy to look at America and despair.

“It’s always been in despair,” he says. “There’s an invalid argument that there was a golden age here. Maybe there was for some people, but that person’s golden age was someone else’s nightmare. On the other hand, when you see the same street-corner building burning over and over again on a 24-hour news cycle, it tends to make it look like the sky is falling.”

When he talks, it sounds like he’s thought about everything he’s going to say well in advance. He speaks slowly and evenly in clear sentences, never stumbling over his words, even when it’s an explosive subject. Here he is, for instance, on the recent spate of police shootings in the US, in which young, unarmed African-Americans were killed by the very people who were supposed to protect them.

“If you’ll allow me to wax philosophical for a moment, people – not just Americans – have a very short memory. US history is short. The Civil War and slavery just happened yesterday in terms of human history, and the United States is still dealing with that. It will always be dealing with that. It defines what this country is and is not. When you see riots in any US city, not just because of the economy or a police killing, it has to do with a very ugly period in our history, which just happened yesterday.”

There’s no undercurrent of controversy for controversy’s sake here. In an era when bellicose swagger is part of the rock star’s job, Neil Fallon is out there on his own.

“There’s a small-town psychology in America that gets exaggerated on a national level,” he says. “We think that we are the centre of the universe. And we’re the farthest thing from it.”

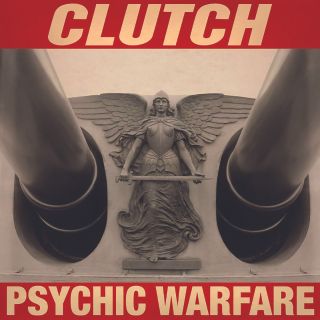

Clutch have just released their 11th album, Psychic Warfare. Like its predecessor, 2013’s Earth Rocker, it streamlines their multitude of influences – hardcore punk, classic rock and metal, the blues, jazz and Washington, DC go-go music – into a relentlessly kinetic whole. Next year marks the band’s 25th anniversary. Both Neil and drummer Jean-Paul Gaster insist they have zero intention of celebrating it.

“Absolutely not,” says Jean-Paul, as upbeat and direct as his bandmate is thoughtful and considered. “We’re turned off by nostalgia. We’re always thinking of something new.”

To understand Clutch today, you have to know where they came from. Getting together in Germantown, Maryland, they were simultaneously removed enough not to be swayed by every passing cultural fad and close enough to the great metropolises of America’s East Coast to latch onto to the important stuff. New York and Philadelphia were four hours’ drive; Baltimore was 45 miles to the south, and the nation’s capital, Washington DC, was on their doorstep.

It was the latter that exerted the greatest gravitational pull on them. The clubs and dives of south DC were their stomping ground, most notably the 9:30 club, cradle of the influential Dischord hardcore scene spearheaded by Minor Threat and, later, Fugazi.

“I can’t count how many times I would see Fugazi roll up to a place that wasn’t suited to a rock show and play under fluorescent lights,” says Neil. “No light show, no t-shirts for sale, they just burned down the house. That bare-bones ethic affected us deeply.”

But they were affected just as deeply, if not more, by DC’s other prominent music scene: go-go. Essentially funk on steroids, go-go emerged in the early 70s as a reaction to the cultural chaos of the late 60s – riots, poverty, racial unrest. It was pure escapism. Sets would last two or three hours, with no breaks between songs. “Chuck Brown, the guy who originated it all, noticed that people would sit down in the breaks between the songs,” says Jean-Paul. “So they just got rid of them and carried on playing.”

If Neil is a fan, then the drummer is a true aficionado. He first came across it in junior high, when schoolmates would play go-go beats on their desks. “There was no way I could get a girl to dance with me at school dances,” says Jean-Paul. “I was such a dork. But they played these go-go records really loud, real deep cuts, which was where I got to hear them.”

Growing up in ethnically diverse DC in the 80s, go-go was inescapable – on the radio, spilling from cars, in the clubs. The go-go scene was populated by larger-than-life characters such as Chuck Brown, the so-called ‘Godfather Of Go-Go’, and ‘Big Tony’ Fisher of Trouble Funk, a band fêted by DC scenester Dave Grohl in his Sonic Highways series. There was plenty of cross-pollination: go-go bands would play to punk crowds at the 9:30 club, or just turn up to watch hardcore bands play.

“Chuck Brown had an amazing drummer named Brandon Finley, and I remember seeing him at a Bad Brains show,” says Jean-Paul. “As a 17-year-old, that blew my mind. I thought these two forms of music would be completely separate, and that I was the only guy who appreciated both. But the punk rock scene was very knowledgeable about go-go. Those bands would sometimes even play together.”

And did they head to go-go clubs themselves? “Oh hell no,” says Neil with a laugh. “Go-gos would be held in clubs that you’d have to be pretty daring to go to as a white suburban kid. Jean-Paul did. He had much more courage than I ever had.”

“I was welcomed,” says the drummer. “I can remember one of the first times, I walked in and the guy on the door says, ‘I gotta pat you down.’ And then he asks me to take my shoes off and turn them inside out. As a white kid from the suburbs, that was pretty jarring.”

In the same way as they assimilated hardcore’s work ethic, so the members of Clutch couldn’t help but take on board what go-go had to offer. “That feeling of groove, I hear that all the time when we’re playing,” says Jean-Paul. “Big beats and big sounds. That’s what I’m thinking when I’m playing. I’m thinking go-go.”

“It was all about the live show,” says Neil. “Playing live music and forgetting about life for a while. We were always of the mind that music should be escapist. We never infused politics into it, which is always heavy in DC punk rock. We were much more, ‘Let’s drink beer, have a good time.’”

What about dancing? Could Neil Fallon dance? “Like a fool,” he laughs.

While go-go culture – and by extension African-American culture as a whole – is part of Clutch’s DNA, there’s nothing on Psychic Warfare that pegs Clutch as a small ‘p’ political band, let alone a big ‘P’ one. In its own way, their music is just as much about escapism as go-go is. Where Clutch’s music is earthy and sinewy, Neil’s lyrics are wrapped up in vivid and frequently surreal imagery. ‘Next thing that I did was tap out Morse code / With a wooden nickel on the receiver of the phone,’ he sings on X-Ray Visions. ‘Before I could complete it, I was quickly overtaken / By the angry spirits of Ronald and Nancy Reagan.’

“I like surrealism for the creep-out factor,” he says. “Whenever I sit down to write lyrics, it’s always an abysmal failure. The lyrics come about when I’m sitting at a red light in traffic or taking a shower, or even singing another song onstage. It’s probably subconscious.”

Given the state of the nation, you’d have thought someone as smart as Neil would have taken up arms – literally or metaphorically. No chance. This is a man who says he’s “definitely not smart enough to be an activist”.

“I find the most positive thing someone can do in my shoes is to provide entertainment,” he says. “To be able to perform and have a person forget about their life for 90 minutes, and have a good time, that’s pretty priceless.”

He insists that he’s never been tempted to write a song that directly addresses what’s happening head-on – a modern-day protest song, basically. Why not? “It’s easy to protest onstage,” he says. “It’s much more difficult to protest with a placard on a street. I find my protest comes just by way of not acknowledging it. I don’t know if that makes any sense.”

Not much, to be honest.

He laughs. “I think musicians are too willing to provide a political commentary. It can weigh a song down in the here and now, and people’s opinions are so all-pervasive in this day and age, whether on social media or the comments pages on a website, that I think it’s worthwhile to not even do that. Just play a damn song.”

What are the good things about America? The things to be proud of?

“The worst day in America is still, for the most part, better than the best day in a lot of other places. There’s an embarrassment of riches here, which I’ve seen through touring. It’s made me appreciate the affluence of this country, an affluence that I don’t think a lot of people realise out here.”

Is America broken beyond repair? “I’d like to think it’s fixable,” he says. “But there’s a sickness, a martial love of violence that gets glorified, and there’s no way of fixing that. It’s part of our culture. And I don’t think it’s ever going to go away.”

If America does burn to the ground? At least Clutch are going out dancing. Like fools.

*Psychic Warfare* is out now via Weathermaker

Party Hard!

Clutch’s essential go-go acts

CHUCK BROWN AND THE SOUL SEARCHERS

Neil: “Chuck Brown was the go-go godfather. He had a hit called Run Joe – I remembered kids singing that in the hallway at school. We use his song We Need Some Money as our intro when we play live.”

Essential listening: Go Go Swing Live (1986)

TROUBLE FUNK

Jean-Paul: “Go-go was really specific to DC, but Trouble Funk were one of the first bands who had a major label deal and tried to break out of the local scene. They were huge in the 80s and 90s, and they still play now.”

Essential listening: Live (1981)

JUNK YARD BAND

Neil: “Junk Yard Band are a second-generation DC go-go band – they literally started their career as kids playing on buckets. A lot of these bands never got signed to labels, so their music was distributed on cassettes recorded live from the PA. Some of their PA tapes are the most rock’n’roll things you will ever hear.”

Essential listening: Live At Safari Club (1997)

EXPERIENCE UNLIMITED

Jean-Paul: “They had a hit in the 80s called Da Butt, and the percussionist on there was a 16-year-old called Heartbeat. He was a youngster who would sneak into the go-gos and sit in with bands. We ended up having Heartbeat play on some of our own records.”

Essential listening: Experience Unlimited (1976)

NORTHEAST GROOVERS

Jean-Paul:“Northeast Groovers are a really powerful band. They have an amazing drummer. They don’t have any records that you’ll be able to find on iTunes – they’re not that kind of band.”

Essential listening: “YouTube – that’s the best way to hear them.”