It begins with the sound of a madman attempting to prise open a terrified Shire horse with a misfiring angle grinder. From the left speaker comes the sound of a freakishly large, exceptionally angry horsefly, no doubt intent on gnawing the surface of my tender young cornea. The, er, man-looking thing on the cover of the album is quite clearly (a) the horse-murderer and (b) the owner – or perhaps, even more upsettingly, the pet – of the horsefly.

The year is 1980. Thatcher and her wet-lipped, stocking-fixated underlings have the country in a lavender-perfumed stranglehold. The homicidal din coming out of the Sanyo radiogram is Iron Maiden’s Prowler; track 1, first album. I look at my brother, jaw agape; we silently agree that we need, immediately, to sport the wizened death’s head and unmistakeable logo of this awesomely rude, hilariously intense band on our clothing. I’m 11. I’m sold. Turn it up (as far as clear parental guidelines will allow, obvs)!

In fact, if the greasy lens of memory allows me to peer into the past without too much distortion, the first time I heard Iron Maiden was on a quite spectacularly good compilation called Axe Attack Volume 1. It was the only more-or-less METAL record we had, and its somewhat odd selection included genuine classics (Paranoid, Bomber) and some rather less groundbreaking material; Frank Marino & Mahogany Rush’s You Got Livin’ amongst it.

Obviously, I still have a soft spot for The Mahogs, simply because they were on AA Vol 1 – not because the track was good, because it wasn’t. Somewhere in there, though, was a song called Running Free, but while it had a bouncy, jump-along optimism, K-Tel’s mastering department – if such a thing even existed – had decided to remove all the metalness, and present it as a big, soft poo of a song, rather than the chugalug belter that’s on the first Maiden album.

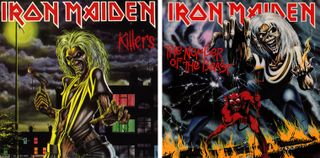

It’s difficult, thirty-five years later, to say whether it was the Elvisly-dead, punk-haired ghoul, or the relentless grinding, bashing and shouting coupled with squalling, TURNTHATRACKETDOWN guitars that was the main attraction in 1980. But, while the actual music became noticeably more polished through the next two albums, particularly after Bruce Dickinson replaced Paul Di’Anno, Eddie stayed. And grew. And became – effectively – a member of the band. Perhaps the most important member.

At the back of almost every young music fan’s mind, on hearing a new act, is one question: “Are they cool?” This translates directly as “Will I be publicly denounced in the playground?” and, ultimately; “Will I forever be denied access to other people’s undergarments?” Deciding to admit liking a band is therefore intrinsically bound up with both one’s own happiness, and the survival of the species.

The objective coolness of the band (or style of music) is irrelevant. For a kid from Catholic school, on the cusp of all sorts of hair-related biological anomalies, a very loud, exciting noise, visually portrayed by an apparently dead murderer and including songs that describe, even celebrate, the act of getting one’s todger out in the bushes and having a good old go on it, is something it’s very, very easy to get behind.

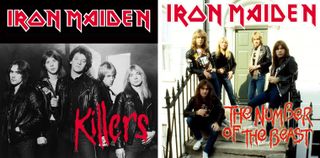

It would have been understandable, but foolish, for Iron Maiden to have given Eddie an early bath, either with the release of Killers in early 1981, or when Bruce arrived in ‘82. Listening to Paul Di’Anno’s less technically exceptional, but equally thrilling scream-alongs, and looking at Eddie’s grisly mug on the covers of the first two albums, bound Di’Anno and Ed inextricably together. But by making the face of the band bigger, freakier and noticeably more evil – look! Eddie is literally in control of Satan! – on the cover of Number Of The Beast, Maiden made it obvious that he was here to stay.

An entire generation of t-shirted and patched headbangers could continue to strut around their local shopping centres wearing the slightly puzzled Eddie, the murderous axe-wielding Eddie, the God-sized Eddie, and those that came later, without splitting into factions. For a band on the brink of massive change, Eddie equalled continuity. Tony Iommi must have been eating his fucking heart out by 1983.

There was, of course, evolution. As the band moved from playing sweaty pubs to even sweatier 4000-seaters, the live version of Maiden’s eternal mascot grew – physically. You might not have been able to see individual band members’ faces too well before giant screens were invented, but you weren’t going to miss a ten foot tall Eddie.

In two dimensions, Ed adapted to suit the themes of each record. His brain – such as it was – was removed for Piece Of Mind (though a McBrain was added, in the shape of Nicko, replacing the dearly-departed Clive Burr in the tub-thumper’s stool.) Eddie subsequently went through stages of Egyptian godhood (Powerslave), future-shock Robo-Coppery (Somewhere In Time), and nightmare-weird, dreamscape body-horror (Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son). 1990’s No Prayer For The Dying album cover can be interpreted as a flashback – Ed looks remarkably like his Di’Anno era incarnation, as he bursts from what one would hope is his own tomb.

Throughout these, and subsequent versions, Eddie bound together a band that’s survived what has been a not-unusual number of line-up changes, given Maiden’s longevity. Eddie sells, both records and merchandise, even to non-fans – remember Miley’s Iron Maiden shirt? Lady Gaga’s? Er, Hilary Duff’s?

Other bands, notably Motörhead, have also settled on a decades-defying mascot and stuck with it; and perhaps it’s inevitable that a brilliant design may, at some point, become a fashion item for people who couldn’t pick either Love Me Like A Reptile or Children Of The Damned out of a bucket if it bit them on the bumhole. And that’s fine – Steve Harris isn’t complaining, presumably.

It’s 1982. Me and my brother, and a selection of Eddie-sporting middle-school rock monkeys are around 15 rows from the Hammersmith Odeon stage. Bruce Dickinson is making an utterly extraordinary noise with his larynx, while looking quite a lot like a freshly Silvikrin’ed spider in shiny black spandex.

It’s a huge spectacle, and the crowd has been several hundred miles north of Apeshit City for at least 90 minutes. Now Eddie takes the stage. I literally can’t believe what I’m seeing. How is it possible for this – thing – to be that tall? I still don’t know, and I’m never going to Google it. The memory is precious. And only a tiny bit comical.