1965 was quite a year. As America groaned under the weight of the burgeoning crisis in Vietnam and racial tensions at home reached boiling point, rock music was at Year Zero. Rubber Soul and Highway 61 Revisited saw The Beatles and a newly electrified Bob Dylan pretty much invent rock music. The ‘counter-culture’ emerged on both coasts (to the east, The Velvet Underground; on the west, The Doors), while Ken Kesey’s LSD fuelled “Acid Tests” in San Francisco led to the formation of ‘house band’ the Grateful Dead and the development of the first proper sound and light systems.

Meanwhile, back in England, The Rolling Stones unleashed “the five notes that shook the world”, (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction, revolutionising the sound of the electric guitar, followed by The Who’s explosive call to arms, My Generation. Rock music had finally been born, although the genre’s elite group of singers – including Rod Stewart, Steve Marriott, Joe Cocker and Steve Winwood – were being referred to in the press as “the blue-eyed soul singers”.

The latest addition to their ranks was a 15 year-old vocal prodigy from Cambridgeshire called Terry Reid. Technically still a schoolboy when he was approached by Peter Jay to front the Jay Walkers, in no time the youngest member of the club was being lauded in the music press.

The interim years have been extraordinary. Reid was present at many of the most legendary events in music history and has been feted by many of its biggest names. Even today, despite the ravages of five decades of rock‘n’roll, his voice remains a thing of wonder. Age has given him the ability to wring every last ounce of emotion from every word he sings. Yet the journey has also been painful. He has faced endless litigation, and endured more bad luck than would seem to be humanly fair. Rather than be wracked with bitterness, he chooses instead to be philosophical and positive. Widespread acclaim may well be long overdue but, to him, it is not essential.

His music might be unknown to a vast section of the population, but – to those who know it – it is treasured and lauded. He is immensely proud of his work and achievements and able to hold his head up high. And yet, in spite of everything, his career is overshadowed by a fable so divorced from reality that it is almost painful: the story that Terry Reid turned down the job of singer in Led Zeppelin.

The first time I heard Terry Reid, I was about 14 years old. I remember hearing music coming from a friend’s room and the singer had the kind of voice that stops you dead in your tracks. It was his version of Stay With Me Baby, and it took my breath away. That was 1974 but it feels like yesterday. In those days, trekking down to your local record shop and spending endless hours flicking through racks of album covers, or crowding into listening booths, just for the thrill of possibly finding something new to listen to, was an adventure. That day, however, I didn’t notice anything else, I just walked straight up to the counter and asked for the Terry Reid album. “The guy that turned down Zeppelin?” the assistant said, “I bet he’s still kicking himself. It’s hard to get, but I’ll order it for you.” Hang on, he did what now? Remember, back then I knew nothing of Terry Reid, but Zeppelin? That sounded wrong. So I walked out empty handed and perhaps a little shocked. I don’t know why but I never did get the album. Even stranger, was that Terry did not cross my mind again for another 25 years.

In 2001, I was living in LA, just up the road from a run-down live music bar called The Joint. On any other night it was virtually empty but on Monday’s it held the “All Star Jam Night”. The crowd, well over the 80-odd capacity, would be shoehorned into the tiny space, just for the pleasure of seeing one of the greatest house bands ever assembled. Waddy Wachtel, the legendary guitarist and X-Pensive Wino whose name appeared on many of the greatest albums since the mid-70s, Neil Young bassist Rick Rosas, Tom Petty’s drummer Phil Jones, and Bernard Fowler, The Stones’ backing singer, made up the core of the band. They’d be joined by whoever happened to be in town and fancied getting up for a jam. The roll call was a Who’s Who of modern music: Keef, Woody, Plant, Daltrey, Neil Young, Joe Walsh, the list goes on and on. Yet whichever member of Rock’s Hall of Fame would drop by, the real highlight of the show was the last member of the band: Terry Reid.

Now in his fifties, yet still with a voice that had lost none of its magic, it was when he launched into Waterloo Sunset that the whole place would visibly come alive. Somehow, like all the truly great ones, he had made the song his own and every week, people would tell me that their dream was to visit this mythical place, Waterloo, before they died. Yet, the same comment would always echo around the bar. “He’s unbelievable, isn’t he? He turned down Led Zeppelin.”

After the show, everyone would hang out backstage, or rather the bar’s fluorescent-lit kitchen (oh, the glamour of it all). Every week people would show up, from Dennis Hopper and James Coburn to George Clinton (now there’s a story never to be told!) and boy, was it fun. But the one night that particularly sticks in my head was the night that Terry, with whom I had only spoken in passing over the weeks, grabbed my arm and said, “Right, it’s time we sat down and got to know each other.” One of the best parts of a musician’s life is that you can become old friends with someone in a hurry and it had nothing to do with the bottle of Scotch or that we were Englishmen abroad. No, that night, we simply became old friends.

Terry had been living in California for 30-odd years by then, yet had lost none of his thick Cambridgeshire burr (‘Los Anglian’ as I call it) and we soon embarked on relentless bout of Python, Hancock and Pete & Dud. I love LA, but even on its best day you yearn for some British humour, and seeing two English guys doubled up laughing (and Terry has one of those laughs that just fills the room), talking in what appears to be code, can be very confusing for most Americans. As we relaxed, we began to open up more and more about ourselves. That was when I began to discover his story. And what a story it is.

Terry was 12 years-old when he joined his first band. They had been working the local live scene for a couple of years, when he realised that he needed to escape out into the big wide world, or London, to be precise. It didn’t take long. He had just turned 15, when he was offered the job with Peter Jay & The Jaywalkers. The Jaywalkers were not exactly your everyday band. A seven piece, with two bass players and a horn section, their Joe Meek-produced debut single Can Can ‘62 had charted but what followed was an array of increasingly bemusing instrumentals, such as the Green Onions-inspired Red Cabbage. The lack of further chart success, however, did not hinder their popularity as a live act. They even supported The Beatles on their 1963 UK tour. But by 1965, Jay had decided upon a fresh approach to success and the addition of the new young soul singer was the key.

Soul has played a vital role in shaping many of rock’s greatest singers. Both genres share an intense passion, overt sexuality and explosive performances. Terry soon began grabbing the attention of the music press, who were quick to label him as one of the exclusive ‘blue-eyed soul singers’, a phrase that had been originally coined for The Righteous Brothers to separate them from their black counterparts but which now applied to a group of singing prodigies whose influences ranged from the blues, to folk and country.

In late 1966, The New Jaywalkers went out on their first major UK tour, with The Rolling Stones, Ike & Tina Turner and The Yardbirds, followed by the release of a new single. Everything was looking good. Imagine Terry’s shock, then, when Jay announced that he was splitting the band. Suddenly the young singer found himself unemployed.

Having started to find his feet as a writer, Terry formed a new blues-rock power trio. And it wasn’t long before they reached the ear of Mickie Most, one of Britain’s most powerful producers,

Most had topped the singles and album charts on both sides of the Atlantic and he boasted an impressive roster of artists, many of whom Terry greatly admired. He willingly agreed to sign an exclusive recording contract.

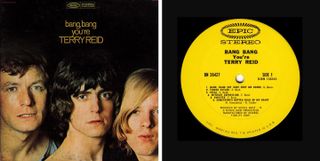

The recording of his first album began in the summer of 1968 but during the sessions the band was offered the chance to open up for Cream on their farewell tour in America. Success in the States had always been Terry’s dream and the opportunity was too good to pass up. Overnight, they went from playing in clubs, to arenas filled with 15,000 fans. The response was fantastic, so they returned home full of confidence and ready to take the UK by storm. Aretha Franklin has famously been quoted as saying, “There are only three things happening in London. The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and Terry Reid”, all of which makes Most’s decision to give the debut album, Bang, Bang, You’re Terry Reid a US-only release, seem even more bizarre.

As a debut, with its eclectic mix of styles, the album feels confused at best. While the vocal performances are undeniably incredible, taken as a whole, it feels disconnected. In those days, with records having an A and B side, finding the right sequence for the running order was an art form that could virtually make or break it, and Bang, Bang… just lacks any real cohesion. There are, however, some shining moments. Without Expression (covered by The Hollies, CSN&Y, and later REO Speedwagon and John Mellencamp) was an early sign of Terry’s songwriting genius, and it could be argued that his cover of Donovan’s Season Of The Witch launched the vocal style that dominated rock music in the 70s.

The second album, Terry Reid, is altogether a far more cohesive record, drawing much of its strength from its diversity. As a fan of Terry’s work, there are many better qualified and far less biased than I to review his work, but the power of songs like Superlungs My Supergirl, Silver White Light and Rich Kid Blues are offset beautifully by the album’s two ballads, July and Mayfly. A large part of Terry’s genius as a singer is his ability to sound vulnerable in one breath and almost dangerous in the next, without ever losing the context of the emotion. Nowhere is this more audible than on Stay With Me Baby, perhaps the definitive version of the classic song.

Once again, though, before the album was mixed, the band had to return Stateside for the Stones famous ’69 tour, and a series of other huge shows including Sky River Rock and the Atlanta Pop Festival. Most agreed to wait for Terry’s return before completing the final mix, so when he returned alone to find that Most had broken their agreement and completed the task alone, Reid was shocked. Feeling angry and betrayed, a huge argument ensued but Most was never one to compromise. He issued the 19-year-old with a clear ultimatum, either step into line and do what he was told or his recording career would be over. Terry was in no mood to be bullied and stood his ground. It was a mistake. Mickie Most simply froze his contract, setting in motion four years of litigation that left Reid unable to record a single note. When the news reached the rest of the band back in America, they felt they had no other choice but to quit. Once again, Terry Reid was on his own.

It had been during this time that the incident synonymous with his name occurred: the myth that he turned down the singer’s job with Led Zeppelin. 45 years on and he still faces questions on the matter in every interview he does. Despite an obvious frustration, he somehow manages to always maintain a dignified smile, as he attempts, in vain, to set the record straight, frustrated in the knowledge that everyone simply refuses to hear him. But this article is about what Terry Reid did (and continues to do) not what he was said to have done, so you will have to wait a while longer for the true story.

Whether Terry fully understood the gravity of his situation, is hard to know. He was still playing to huge crowds but he was broke. It’s a story that is hardly unique for the time. Everyone from The Beatles right down to musicians simply trying to earn a living wage had fallen victim to an industry rife with theft and litigation. Even The Stones had recently discovered that not only had they no money but they had also lost ownership of their music. For some, the pressures proved too great.

Contractual disputes and pending lawsuits were a key factor in pushing his friend Jimi Hendrix over the edge but Terry wasn’t looking for a way out, all he wanted was to find a band. As it turned out, it was the band that found him.

Back at the ’69 Sky River Festival, Terry had met the enigmatic multi-instrumental genius David Lindley. They had talked about one day working together but even Terry was surprised when Lindley, with his family and Samurai sword in tow, arrived in England ready to start work. They recruited Ike Turner’s bassist, Lee Miles and John Lennon’s drummer, Alan White and set up camp in the heart of the Cambridgeshire fens, where they set about writing what would eventually become the River album.

Although they couldn’t record, they could still play live. Their first major show was on the opening night of “the largest ever gathering of humanity” in front of 700,000 people at the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival. Yet, for all his live success, trying to work under the constant shadow of the litigation (added to the American contingent’s dislike of the British weather) was proving too much and the band decided to relocate to LA. By now, Atlantic boss Ahmet Ertegun was interested in signing them but even for one of the most powerful men in the industry, there seemed to be no quick fix to the Mickie Most situation but now, at least, they were suffering in the sun.

The summer of ’71 proved to be a memorable one. As part of “the greatest mass exodus of rock royalty the country had ever witnessed”, Terry flew to St. Tropez to play at the wedding of Mick and Bianca Jagger. Then, a month later, they became the very first band to appear in front of 10,000 people, bathed in the afternoon sun, on the Pyramid Stage at the Glastonbury Fair. The event, which was somewhat different to today’s behemoth, was a free festival that also featured Traffic, David Bowie and Fairport Convention. Fortunately, it was documented in a film by Nick Roeg, which is enjoyable as much for the psychedelic drug-fuelled crowd scenes as it is for the music. The highlight, however, is a stunning 10 minute performance of Dean, which captures Terry and the band right at the top of their game.

It was a further two years before all the legal issues were finally resolved and, in 1973, River was at last released on Atlantic Records. Like any artist who has been working on a project for three years, on two continents and with two producers, it is almost impossible not to lose some form of perspective. Songs had been worked and re-worked, recorded and re-recorded. In fact, on top of alternate versions and mixes, there are at least four albums worth of other material left over from those sessions, so, in the end, River is actually best described as two separate albums.

The first side is reminiscent of the Allman Brothers at their very best; funky rock grooves laying the foundation for Lindley’s astonishing country-blues pedal steel playing. Whereas side two is what I would call the sound of summer. Opening with the album’s masterpiece title track, which was inspired by Gilberto Gil, the Brazilian musician and political activist, who Terry had housed in London following his exile from Brazil. The song is best described as a journey, weaving effortlessly through Latin rhythms and melodic acoustic guitars. Vocally, it’s the album’s diversity that showcases Terry’s genius as a singer. From the powerful soulful rock to beautiful romantic melancholy, the man proves that his delivery has no boundaries. From Chris Robinson to Robert Palmer, singers have cited the influence that it had on them.

Yes, there are ‘jam’ moments, but this was 1973, for fuck’s sake, what do you want? This was an album that was never going to be an overnight success. It needed the label to invest their trust and time — as well as their money — in it, but Ertegun was reportedly disappointed in its duality, which resulted in negligible support. The result was yet another wonderful album that simply faded into oblivion.

Having invested so much of himself in the project, Terry could easily have become disillusioned by its lack of success, but instead he moved into Bob Dylan’s house up in the Hollywood hills and became part of the fabric of the LA music community. It was here, over the next couple of years, that he wrote the songs that would go on to make up his finest work, Seed Of Memory.

In any era of music, the role of the producer cannot be underestimated. With today’s advanced technology, almost anyone can record music in the comfort of their home, which has led to an environment whereby technical skill has surpassed the understanding of the natural sonic possibilities of instruments and the space in which they are recorded. Production is all about the relationship between artist and producer, beginning with trust and the ability to communicate and leading to a shared vision that brings out the very best in the songs. Undoubtedly born out of his experiences with Mickie Most, Terry must have become a hard man to produce. He’s incredibly strong minded and he writes and plays from the heart, from instinct, and musicians like that need a strong producer to harness that raw energy and yet still create a thread and balance. Thankfully, Terry had just such a man.

Terry had known Graham Nash since his Hollies days. Graham was both a friend and a hero, which made the incredibly hard task of placing himself totally in someone else’s hands again, perhaps a little easier. For his part, Nash brought a discipline to the proceedings that Terry desperately needed, insisting upon Reid’s full focus. This was duly delivered.

Lyrically, Seed Of Memory is a work of art. Every track tells a story, in the vein of the great balladeers throughout history. His ability to take subjects of a personal nature and not weaken their impact by smothering them in self-indulgence is remarkable. The Frame, for example, is a torch song to the pointlessness of litigation, which could have so easily been lost had it been drowned in any personal bitterness, and Brave Awakening, a heart-wrenching lament to the decline of a coal industry — in which generations of his own family had worked — retains its power by not becoming a politically barbed protest song. The album manages to include a mixture of shades and styles without any track feeling out of place. The epic title track, which tells the story of how screen legend, Marlene Dietrich would visit the frontline troops during World War II and offer more than just a cheery wave to boost their morale, could easily have gone the same way as River but Nash somehow finds a way to feather it in perfectly, alongside the beautiful, prayer-like To Be Treated Rite, a haunting ballad inspired by the old Spanish mission bells that still adorn California’s Highway 1.

The album was released on ABC in 197, to a slew of positive reviews and major radio airplay, but what nobody knew was that the label was on the verge of bankruptcy and subject to a take over by MCA. With all their assets frozen, there could be no promotion, and Terry couldn’t get any of the money he was owed. “I didn’t come out with enough for the cab fare!” he says. Yet again, just as he was knocking on the door of commercial success, he had to watch another album just fade from view. Had he been a boxer, he would have just stayed on the canvas and taken the full count but, somehow, from somewhere, Terry Reid found the strength to get up yet again.

In 1976, now signed to Capitol Records, Terry went back into the studio, this time with Rolling Stones/Peter Frampton producer, Chris Kimsey. Kimsey wanted to capture the real excitement of the band’s show, so after just two days rehearsal, they went in and recorded Terry’s most live sounding album to date, Rogue Waves.

It’s a record that is layered with guitars and finds Terry’s voice at its most powerful, although the surprise comes in the form of two cover versions. Phil Spector’s Baby I Love You receives a wonderful rock overhaul and All I Have To Do Is Dream is given an arrangement of haunting simplicity, around which Terry showcases his genius for turning a song inside-out and making it his own; a skill that only a handful of artists have ever really mastered. Following the tragic death of his great friend Carl Wilson, he was asked if he would play at the memorial service. Armed with just an acoustic guitar, he began playing an unrecognisable slow bossa nova groove, which he proceeded to turn around at will, confusing the gathering even further, which was made up of all those who had shaped American music in the 60s and 70s. It was only when he sang the words “there’s something burning up inside of me…” that the shocked masses — including Brian Wilson — realised that he had turned the classic Don’t Worry Baby into a stunning acoustic ballad all of his own.

Rogue Waves was released and the band set straight off on a promotional tour. This time they were secure in the knowledge that they had the label’s the full support, but a few shows in Terry began to worry when his calls were not being returned, and he went straight round to Capitol in person on his return to LA. The notices posted at the main entrance told the story. The label had been merged into EMI Worldwide, and all its product was in limbo. So Rogue Waves drowned before it could even swim. How could this happen, yet again? If it wasn’t for bad luck he wouldn’t have any luck at all.

But he was still just 30, so he retired back up to the hills and seemed content to do session work for, amongst others, Don Henley, Bonnie Raitt and Jackson Browne. Yet, all the while he continued to write, and it was these songs that arrived on the desk of long-time fan and Warner UK chairman, Rob Dickins, a decade later.

Dickins had an idea. He flew Terry to London to begin work on his most surprising collaboration to date, with the producer Trevor Horn. Terry was largely unfamiliar with Horn’s work but he was already working with Hans Zimmer on the soundtrack for the Tom Cruise film Days Of Thunder and, somehow, the three men clicked. The result was 1991’s The Driver. The album sounds ‘big’, as befits that era and it features an all star cast, including Enya, Stewart Copeland, Joe Walsh and Tim B Schmidt. Two of the songs, Gimme Some Lovin’ and The Driver, ended up on the movie’s soundtrack, but it’s the ballads Hand Of Dimes and Fifth Of July that sit head and shoulders above the rest.

It was decided that the cover of Whole Of The Moon should be the first single, but even as the record was being pressed, The Waterboys re-released their original version, which went to no.1 and all momentum was once again lost. Finally, Terry Reid had had enough. The next few years saw him playing live shows from time to time and he collaborated with ex-Stone Mick Taylor, Jack Bruce and Don Felder, but little came of it all. His songs continued to be covered by artists such as John Mellencamp, Marianne Faithfull and REO Speedwagon, and were featured on various TV shows, such as Baywatch, but like many artists of his generation, the MTV-led industry was unrecognisable to him and he, in return, to it. Music had taken a back seat to image, and those who didn’t fit in became refugees in their own industry.

Genius must be a heavy burden to carry, but without the support of someone you can trust to handle your business, it can be nothing short of destructive. Where Neil Young has always had Elliot Roberts to negotiate and facilitate the twists and turns of his career, Terry has been mismanaged and unsupported. Perhaps he’s not blameless in this but then again, if you give a kid from rural England the keys to America, with an unlimited supply of free drugs and women in every town, just staying alive is miracle enough. The reality is you just want to write and play music and somehow that became impossible for so many people. There is so much luck involved, particularly in finding the right business partners, and that very much lies in the lap of the Gods. Reflecting on Terry’s career, there are two artists who always spring to mind.

Orson Welles was a 23 year-old star of the stage and radio, when he signed a contract with RKO Pictures that was unprecedented in Hollywood history and gave him total artistic control over his work. Three years later, despite the studio’s attempts to suppress it, his first film, which he co-wrote, produced, directed as well as starred in, Citizen Kane, was released. Six months later, this masterpiece which today is still considered by many to be the greatest movie ever made, was withdrawn and shelved, where it remained for the next 15 years.

The reason was that Welles dared to take on the establishment. His disdain, brought on by their broken promises and interference, in the end led to the termination of his contract, after which he almost never worked within the Hollywood mainstream again.

Bruce Springsteen, on the other hand, is an artist who is blessed with discipline in spades, but he is also well known for his refusal to compromise on the sound that he hears in his head. During the recording of Born To Run, all he could say was that he wanted “the sound of Roy Orbison singing Bob Dylan, produced by Phil Spector”. That one track alone took six months to perfect and undoubtedly contributed to his split with manager/producer, Mike Appel, a scenario that directly mirrors the Reid/Most affair. Their ensuing legal battle meant that for three years he could not release a follow up album. But the difference in the two situations was the arrival, for Springsteen, of Jon Landau, the man who has guided his career ever since.

All these men are great storytellers but in very different ways. Young, Springsteen and Welles are acknowledged as some of the greatest writers in history but their work can often be dark and barbed. Terry, on the other hand, lacks that global recognition but the boy who essentially left school at 12, is responsible for writing that is every bit as poignant as any of the great poets ever were. For Terry, any anger and despair is disguised behind his humour and hope. Even today, when asked about the man who broke his promises and then chose to destroy the career of a teenager who stood at the crossroads to greatness, rather than back down and admit he was wrong, all Terry will say is “I have no animosity towards Mickie Most.” Those words alone, says everything about the man.

And so, to the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth… It was during the summer of 1968 that The Yardbirds split up. With a short tour of Scandinavia already booked, bassist Chris Dreja and guitarist Jimmy Page decided to fulfil their obligation by hiring new members just for the shows but Dreja pulled out, leaving Page, who was now not allowed to use the name, told that he could bill the band as The New Yardbirds. So all he needed was that band.

Because they were both involved with Mickie Most, and represented by his partner, Peter Grant, Terry was asked if he was interested in standing in as the singer for the dates. Although it would have been fun, the timing was less than perfect. Work had already begun on his new album and the dates clashed with The Doors/Jefferson Airplane tour on which he was already booked, so he was left with no alternative but to refuse. Soon after that, however, he bumped into two old friends, Robert Plant and John Bonham from the Band Of Joy, who had played on the same bill as Terry many times in London’s Kings Cross. Apparently their band had recently split and Plant was now fronting the gloriously named Hobbstweedle, while Bonham, he says, was disillusioned and talking about giving up altogether.

Terry took them to a local café and told them about a new band being put together for which they would be perfect. He then took them straight round to the RAK office to introduce them personally. The rest is history. Terry never, in fact, turned down Led Zeppelin. There was no Led Zeppelin. He simply turned down nine shows with The New Yardbirds. If anything, Terry should get the credit for his major role in the band’s creation.

The whole “what if…?” is ludicrous. While they would certainly have written some great songs together, it was Jimmy’s band and Jimmy’s vision, and he wanted a front man. Terry, a great guitar player in his own right, would never have been content to be the singer alone. In the most simplistic terms, what became Led Zeppelin could only ever have existed with the four members that were its make up. Any suggestion to the contrary is arrant stupidity.

In 2004, when Plant got up to sing with his old friend at The Joint, he told the crowd, “This man should have had my life… mind you, I’m not sure he’d want it!” Terry’s reply was typically tongue in cheek “I wouldn’t mind some of the money!”

But the result of this story is that Terry’s career has always been viewed in negative terms, focussing on its failures. Any mention of his work is prefixed by, “what could have been”. Nobody talks of his triumphs. His songs, his live performances, his albums, that are now starting to be referred to as forgotten classics, and, of course, that incredible voice, with which he could effortlessly deliver any style, without compromising a drop of emotion.

I can only end by saying this. There will be a few more tours, so do yourself a favour and go and see what you’ve been missing. A Terry Reid live show demands your attention for so many reasons. It doesn’t matter if you don’t know his work, because by the time you leave, you will. I’ve seen people after a show downloading his entire back catalogue. Whether it’s his voice, his style of playing, his anecdotes or the sheer emotion that oozes out from inside him, his is a performance that has to be seen to be believed. I’ve worked with him, played with him and watched him and believe me when I say that even on stage you don’t know what’s coming next. He has never played a song the same way twice. Arrangements, set lists, even keys, mean nothing. His heart controls the entire emotional rollercoaster ride.

He will probably shout at me for saying this, but I’m going to anyway: Terry Reid is entitled to the success which has eluded him. Perhaps if he was to take his guard down just one last time and allow someone in to guide him through the making of just one last album, which both we, and more importantly he, so richly deserves, then just maybe there could be a happy ending to this tale. I’ve heard many of his vast collection of unrecorded songs, and believe me when I say that, in any era, many of them are quite simply classics. Now, more than ever, we need great songs. Catchy tunes, however good, are no substitute, and that these songs might never see the light of day would be a crime that we must stop, before it’s too late.

“God how they’ll love me when I’m dead,” Orson Welles used to say. Please don’t make Terry Reid wait that long.

*Superlungs*, a documentary about the career of Terry Reid featuring interviews with Graham Nash, Robert Plant, Eric Burdon, Gilberto Gil, Linda Lewis, Michael Kiwanuka and many more, is currently in production.