“Mott were his band,” said Ian Hunter, while guitarist Mick Ralphs paid tribute to “the engine room of Mott”, after drummer Dale “Buffin” Griffin lost his battle with Alzheimer’s disease last Sunday. His former comrades might have been front men, but Buffin insisted on his big yellow Premier drum-kit being placed closer to the crowd than was usual in the early 70s which Mott The Hoople came up in.

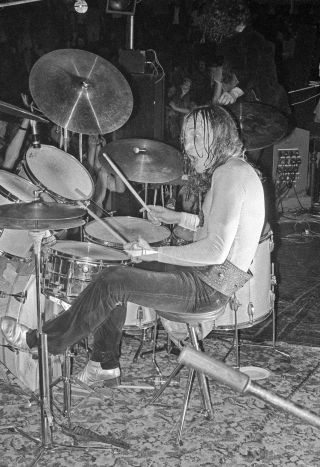

Although Buffin was a quiet man on the surface, this bold statement could be seen as a symbolic representation of his pivotal role in the band. While rock already had its emerging superstar drummers, such as Ginger Baker and Mitch Mitchell, Buffin knew he was there to anchor the chaos which raged around Mott the Hoople’s early live performances, then became a concerned backroom force as the group progressed from their riotous early club dates into being a top ten act.

By the time the band struck out on its own on the Mott album, which signalled their golden run of hits in 1973, Buff had become a principal studio voice and, at one point, insisted on doing press interviews as an articulate band spokesman, always sporting an elegant suit.

Buffin always seemed to be trying to show that a band’s drummer could be much more than just its timekeeper and, if anything, a leader. In several ways, he was the band’s quiet tornado. He had helped form the original Mott The Hoople and felt passionately about the raw deal they often got from snooty contemporaries, who dismissed them as young punks. And although unfailingly pleasant to my wide-eyed teenaged self, Buffin could be volatile, clashing with Hunter famous in an onstage fight in a disused Swiss gas station in March 1972.

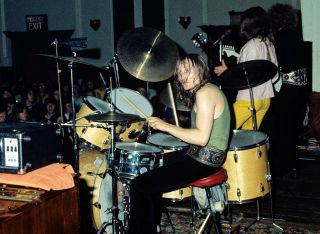

Buffin was the first drummer I witnessed in action from close quarters. One night in December 1969, he parked his kit in the centre of the 18-inch high stage of Aylesbury Ex-Servicemen’s Club, where Friars Aylesbury presented bands of the day and future stars. I watched open-mouthed as he laid into his drums, displaying particularly funky cowbell-snare interaction as he twirled his sticks, threw battered ones over his shoulder and drove Mott along their newly-discovered wild side on rockers such as Rock ‘N’ Roll Queen, the Youngbloods’ Darkness Darkness and the epic tear-up through the Kinks’ You Really Got Me, which brought out all the idiot dancers.

Mott looked unusually cool that night, with their ‘grandad’ vests, Kensington Market scarves, astonishingly long hair and early examples of the platform boot, but Buffin was dressed for work in his favourite sleeveless vest with a big star on the front. He soon established himself as an immensely-powerful motor that drove the rampant rockers and added sensitive drama to the crashing ballads, which they turned into an art form on outings such as Half Moon Bay and their version of Sonny Bono’s Laugh At Me. As Hunter says, “He not only played to the song, he played to the lyric.”

The week after the Friars appearance, Mott were booked in for my school’s Christmas dance (The following year we had some unknowns called Genesis). Trouble was, it was sixth form only and I was a lowly 15-year-old fifth former. Disgruntled, I repaired to the pub over the road. Who should be sitting in the corner but Mott? Summoning all my courage, I approached their table and gushed about last week’s gig. The band were immediately friendly, bought me a pint and, when I said I couldn’t get into the gig, spluttered in outrage and sneaked me in as a roadie so I could watch their deafening set while hiding under the PA.

That particular night of personal rebellion and defiance — and the one two years later when I sat with Bowie after he’d just unveiled Ziggy Stardust at the same local club — remain twin turning points in my life. Along with future stars such as The Clash’s Mick Jones, I now followed Mott at every opportunity, seeing them everywhere from grimy town halls to the Oval Cricket Ground, along with more visits to Friars Aylesbury.

A fierce devotion to the original rock‘n’roll spirit was instilled in Buffin at an early age by his parents who, in time-honoured fashion, had passed it on. Speaking a few years ago, he remembered getting that first drum kit; the same one which held me in awe at that first gig; “Both my parents were very young and liked rock ‘n’ roll, so that’s where it started. I just took to it. My dad and my mother liked that. It was quite handy really, as they bought me a drum kit. I was expecting some tiny little thing but next thing I know, I’ve got a full size Premier Kit, which they got on the never never. I used that for years and years. That’s how I got into music. At that time, I was still at school with Overend Watts. When people saw that drum kit they were like ‘Woah’. They’d never seen anything like it in that area. So I was in; just to have this drum kit was enough. So that was how I got the bug; big time.”

Once he’d grown big enough to take on his kit, Buff started playing in local bands with Watts, which brought him into contact with future Mott members Ralphs and organist Verden Allen. “Very strange to think these little lads from school went that far and did as much as we did,” reflected Buff. “It’s not the greatest thing that happened in the world but talking about it now, it’s quite astonishing that from that little acorn Mott The Hoople grew.”

Grow they did, through 1970 and ’71, when Mott seemed to be touring endlessly, although playing to a core crowd who didn’t number enough to send the four albums they recorded for Island into the charts. I could see band morale getting progressively lower every time I visited the dressing room. Although they were still friendly, there was a discernible aura of desperation around the group and Buff often hardly spoke. It came as no surprise when word came they’d split, apparently after Hunter and Buff’s onstage fight in Switzerland, but nothing could prepare anyone for Bowie’s gallant rescue donation of All The Young Dudes after Overend phoned him looking for a job.

“Bowie came along like a huge ray of sunshine,” remembered Buff. “He believed in the group. We’d had a terrible time in Switzerland, where theoretically the group had broken up and that was the end of Mott The Hoople. Of course, that’s total bullshit, I never believed that for a second, but we got over that business and then things started to take shape a bit more. Bowie was great to work with in the studio. It was just a breeze to him. He was able to create this feeling that anything he did was going to be good, and people were going to like it, and it was going to sell, and of course that first record did reasonably well.”

That’s one way of putting it. Suddenly, Mott were pop stars, appearing on Top Of The Pops with that summer’s anthem. “The first time I heard it was out on the street one day, and I thought, ‘I know that song,’ and it was Dudes. That was a great shock, cos it was on all the radio stations and everything. I thought ‘God, this is another world, this is something different.’”

Moving over from helping with Bowie’s fan club, I started running Mott’s for the MainMan organization in mid-1972. Buff was often the most helpful band member, sending postcards when they were on tour, writing newsletters and leading the rest of the band signing photos to be sent to members such as Morrissey and Benazir Bhutto. He was particularly tickled when I told him how the future Pakistan Prime Minister had turned up on my doorstep one day, while at university in Oxford. I remember blowing up balloons with Angie Bowie to throw off the balcony when Mott played their big Rainbow Theatre gig, which saw their set end in gear-destroying frustration at recent events and the dodgy sound. It was the only time I ever saw Buff trash his precious kit.

I’d been used to Mott taking the stage in their Ken Market boots; flash but cool. Although they had little in common with novelty glam bands such as Slade and Sweet, nothing prepared me for the sight which greeted me when I walked into the dressing room. Hunter was looking uneasy in a black leather jump-suit, Overend sported platinum hair and Buff was sitting there in a vest made of shiny bits of metal, all set off with a touch of makeup. Glam had struck Mott and, although they were now successful, it cost them their original loyal following.

This rankled particularly badly with Buff, who later declared (in a comment which might be considered sacrilegious in the current climate), “The worst thing that happened to Mott The Hoople was David Bowie. It was nothing David had done, but All The Young Dudes killed our audience stone dead. All the fans who had stayed with us for quite some time just went in a flash. It really did come as a shock that they didn’t want to know any more. I don’t know if we ever overcame that. Once they got to understand who Bowie was, they started to understand the minor part we were playing in that. Certainly, a lot of the audience took umbrage at Dudes, which was certainly the best thing we had ever done, but it was difficult for us to understand that a big part of the audience didn’t want to hear this new song.”

Buff knew that a hit was necessary to save Mott from oblivion, but when Bowie offered them Drive-In Saturday as a follow-up, they turned it down and, by early 1973, were out of MainMan’s orbit, embarking on the golden path which saw the landmark Mott album and hits including All The Way From Memphis and Roll Away The Stone, by which time his old Hereford pal Ralphs had left to form Bad Company, replaced by former Spooky Tooth guitarist Luther Grovsenor, aka Ariel Bender..

“It was really good fun for quite a while, recalled Buff, “ but Tony Defries [MainMan manager] was a very nasty chap and we wouldn’t have been able to work with him on any long term basis. Most of us were glad to see the back of him. He was not good news at all.”

Being forced to go it alone had visibly strengthened the band when I sat with them to hear the final playback of Mott at AIR Studios on Oxford Street. This one they’d done themselves and Buff was now happily learning the ropes in the studio. “Mott certainly improved a lot as time went by. We knew more about recording and stuff like that, so that was helpful.” When Mott toured the UK in late 1973 it was as the country’s new rock stars, although they could still pull off the occasional riot, like at Hammersmith Odeon (supporting was a hot new band called Queen, whose Brian May tweeted a tribute to his “old comrade” Buffin this week).

But recording of 1974’s The Hoople album was fraught, cracks opening up within the band as their success grew, particularly in the US. Mott became the first band to do a stint on Broadway, selling out a week at the 1900-capacity Uris Theatre that May (making the Guinness Book Of Records). Although they were now treated like rock royalty, opening night was sabotaged by a gatecrashing Led Zeppelin, fresh off a drunken Concorde flight and full of themselves.

After Buff refused John Bonham’s demands to play his kit, “somebody from the Zeppelin guys booted me in the knee,” he recalled. “They were in a bit of a state but it completely ruined the gig. I remember getting a very fat knee. I was hobbling around and the knee was just getting bigger and bigger. I don’t know why they did that. They were the biggest group in the world; I just thought it was very sad they chose to do that. They didn’t need it, we did.’ Hunter reckoned it was the only time he ever heard their manager Peter Grant apologise to anyone.

Things went from bad to worse when Bender was replaced by Mick Ronson, who Buffin always remembered refusing to speak to the band, apart from Hunter. It was still hurting him 30 years later. “That was a big problem for me. It was just bizarre. Why Ronno wouldn’t speak to anybody but Ian, I don’t know.”

When Hunter and Ronson unsurprisingly broke away from the band, Buff, Overend and Morgan Fisher soldiered on as Mott. I liked these three so much as people that I stuck with them and started a new fan club for them, the Hot Motts. Of course it wasn’t the same but there was never any denying they were now the underdogs again, fighting for their lives and their new music to be heard. I’d go round the Wembley flat, where Buff lived with a former Page Three girl called Paula, who he had married in 1973 (It didn’t last long). They even gave me a little Shi Tzu dog they’d rescued from Battersea Dogs Home but couldn’t keep in their little flat. Buff was always in touch, pleasantly helpful (and wickedly funny as the three deployed their surreal inter-band catchphrases and weird noise which you have to have been there to appreciate).

We gradually lost touch as I became swallowed by punk. Buffin and Overend set up a production company, producing Hanoi Rocks, The Cult and hits such as Department S’ Is Vic There?. Dale Griffin then became the production credit on over 2,000 sessions for John Peel’s Radio One show, including a memorable Nirvana session in 1990.

Next time I saw him was when Mott announced their shock reunion of October 2009, which saw a delirious stretch at their old Hammersmith Odeon rioting ground. He’d been waiting for this moment ever since Hunter pulled the plug 25 years earlier but, in a cruel twist, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s around the same time. When I saw him that week, it came with a devastating realisation that he sometimes didn’t have a clue who I was, although I obviously looked familiar when he smiled a lot and repeatedly declared “it’s just like old times.”

In a way it was, but not for Buff, who had to sit out his dream in the wings as the Pretenders’ Martin Chambers, an old Hereford buddy, sat in on drums (although he did make it up there for the encores, including that song Bowie gave them). These gigs were the last time Hunter saw Buffin, recalling “He was eloquent and aware and had a great time doing the encores. I’m so glad he was able to do that.”

After that, I tried to keep tabs on his progress, with Verden telling me he’d gone into a nursing home a couple of years ago. During those years, he always had childhood friend, now partner, Jean Smith at his side, unselfishly caring for him as the disease increased its soul-diminishing grip. Still a fighter, Buff strove to bring attention to this often overlooked disease, declaring in an interview that “Inside I’m still the same Buffin!”

For me, he will now always be the same Buffin I first met 47 years ago, one of modern rock’s original powerhouses and an absolute gentleman, who truly deserves his place in history. As one of Mott’s most gorgeous ballads said, Rest In Peace.