“If we were going to go down in flames then they were going to be our flames.” – Geddy Lee

“I think it’s fair to say we didn’t feel defiant doing it. We just figured it was going to be our last hurrah, the one last time Rush got to make an album.”

Geddy Lee is sitting in the Milestone Hotel overlooking the swish Kensington Court in West London. He’s here to talk about the band’s latest, and possibly last, concert DVD, Rush: R40 Live, amid rumours of his band’s demise and on the day when drummer Neil Peart appears to have dropped a bombshell via an essay for Drumhead magazine that suggests he’s finally retired from the band.

Lee’s been batting away break-up rumours all afternoon when Prog sits down with him to talk about a time within Rush when it wasn’t their fans or the media who thought they were calling it day, but the band themselves – though not by choice.

Between March 1974 and April 1976, Rush had released four studio albums and in doing so had careered between bluesy bar band and theatre headliners, at least in some parts of Canada and the US. Gene Simmons and Kiss had taken Rush under their wing, and they’d lost one drummer only to gain another who, as Geddy remembers, “knew a lot of fancy words”. And in 1975’s Fly By Night, they had not only created a Juno Award-winning, platinum-selling record, but also found themselves in the elevated position of the next Canadian band ‘most likely to…’

But Rush, not least Lee and guitarist Alex Lifeson, were becoming constrained by the more pointed – some might say inhibited – writing that populated their debut and were keen to push the creative envelope with the weighty, atmospheric battle of the underworld also known as By-Tor & The Snow Dog. In retrospect, it was Rush’s creative tipping point. In not much more than a year, they’d gone from writing a blue-collar anthem like Working Man to crafting a trippy tale of Hades to close out side one of their second album.

Then again, given that it was a teenage Lee and Lifeson who had camped out overnight to see Yes play live at Massey Hall in Toronto some years before, no one can have been that surprised when they started trying to emulate some of their prog heroes.

Caress Of Steel, recorded in either two or three weeks – Lee and Lifeson can’t seem to agree on this – was released in September 1975. Fly By Night had appeared in stores in February of the same year, and while Caress… was clearly an extension of the work they’d begun to do on Fly By Night, it was met by a critical response akin to angry villagers spotting Frankenstein’s monster on a nearby hill, rather than with a considered critique of their music. It went gold in Canada, compared to Fly By Night’s platinum status, but it alienated not only their audience but their record label too. Side one ended with the florid, 12-minute The Necromancer, while all of side two was given over to the conceptual The Fountain Of Lamneth.

“We’d seen a list of the label’s financial estimates and predictions for the following year,” says Lee, “and we weren’t even on it.”

The band were so broke they were unable to pay their crew, audiences thinned and Rush dubbed the subsequent live dates as the ‘Down The Tubes’ tour. Their label were haranguing them for snappier and more radio-friendly material akin to some of the songs they’d recorded for Fly By Night. “But if we were going to go down in flames,” says Lee, “then they were going to be our flames.”

Retrospectively, it’s now easy to see how the experimentation highlighted on the band’s second and third albums helped create Rush’s defining record (well, their defining record until Moving Pictures came along).

“We’d never have made 2112 unless we’d made Caress Of Steel,” Neil Peart told Prog over lunch in Laurel Canyon as the band were mixing down their last studio album (and one that embraced their conceptual bent with glee), 2012’s Clockwork Angels. “You only have to listen to that and then go listen to 2112 to see what we were trying to do and then how we did it – that seems so obvious to me.”

“The best thing about 2112’s success is that because the label were so against it, when it did take off, they could never tell us what to do again.”

Less so to their label, who were anything but thrilled to find that the band had opted for another side-long conceptual piece inspired by author Ayn Rand (who had also been the spark for the song Anthem that opened Fly By Night). It followed the travails of a young hero cast adrift in a futuristic dystopian society ruled by a hierarchy of priests. Music is banned, but he finds a lost guitar that ultimately leads to civilisation’s emancipation, and his own death. Imagine pitching that idea to a record company executive who was hoping for Making Memories part two.

Listening to 2112’s bombast now, it’s easy to forget that it was mostly written on two acoustic guitars, usually in a hotel room or on the road between shows.

“Yeah, that was pretty much how we wrote it,” says Lee. “It’s a handy thing, the acoustic guitar – you didn’t need an amp, you could do it in our Holiday Inn room, you could write in the back of the station wagon we were travelling around in. As long as you’re strumming the acoustic hard, it sounds heavy, so if you write the part on it, you can imagine what it’s going to sound like through electric guitars and amps. So, it’s not a big stretch really to write that way. We went back and wrote [2007’s] Snakes & Arrows that way too.”

“The strange thing with 2112, it just kind of flowed; one song came out of the other. I remember that Alex and I had some very definite ideas of the kind of music we wanted to write, even before we saw the lyrics, the overblown intro, the pacing, the movements that were involved. And then Neil had written these lyrics and it was almost magical how well they worked. We didn’t really change any of them – they just inspired us to put the music together even more. It just started to happen.”

The cards fell kindly for Rush on 2112. Long-time artistic director Hugh Syme created the now famous Starman logo (as well as contributing keyboard and mellotron parts to the album) with the simplest of briefs from drummer Neil Peart.

“The evolution of the star and the man was my first true collaboration with Neil,” Syme says now. “He simply described the Red Star Of The Solar Federation as being all that is contrary to free thought and creativity, and the man as our hero. I simply combined the two. Never was this intended to be the band’s brand or logo, with such a strong and enduring association with all things Rush.”

A few years later, Alex Lifeson shared his thoughts on why he thought the Starman logo had endured so well, and what the secret to its longevity and association with Rush might have been. “The naked bum and the fist, I think,” he said without blinking. “That’s it, the bum and the fist.”

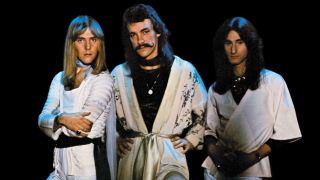

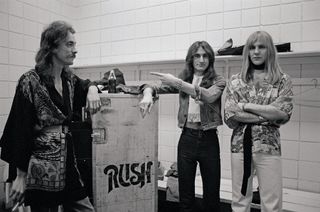

And while the cover and inner artwork were heavy on symbolism, the back sleeve was given over to a rather po-faced Rush dressed in what could only be described as kimonos.

“Ah, the kimonos, that’s what they were,” says Lee with a laugh. “Didn’t you think they were swish?

“You know, people and our management kept saying to us, ‘You need a new image.’ And it’s true – we weren’t very image-orientated. So I remember we were in San Francisco and we’re staying at the Miyako Hotel, which is in the Japanese part of town, and we said, ‘Okay, let’s go buy some stage clothes and get an image happening.’ We just walked around the Chinese area and we found these kinds of colourful robes and said, ‘Okay, let’s try this,’ and that’s what we did. I mean, some people liked it…”

He regards Prog evenly over his round glasses. “But that straw fedora Al’s wearing on the inside sleeve, nobody told Alex to bring that hat with him. That was all his idea.”

“The best thing about 2112’s success,” says Neil Peart, “is that because the label were so against it, when it did take off, they could never tell us what to do again.”

“It’s true,” says Lee, “and I think it’s also fair to say it saved our careers. But it’s not even like we really had any instinctive sense that it would do any better than Caress Of Steel had done before it. We liked Caress Of Steel! Of course, every record you make you think is better than the one before, but you’re easily fooled by yourself because you can’t really be that objective. But I think we had a feeling it was a good record and we were proud we were going out on a good record; that if this was us saying goodbye then it was a good way to go. But we had no idea it would connect with people the way it did.”

And like a bat making contact with a well-weighted baseball, connect it did. Sales may have started slowly, but it would go on to reach multi-platinum status in both Canada and the USA.

“Oh yeah, it did well, but we were still way in debt,” says Lee with a grin. “But we were paying it off and 2112 was helping us pay it off. It took a while, but there was a buzz as soon as the album came out. It didn’t sell a lot immediately, but it was steady and it kept building. As we toured it, it kept building and building, and over the next three years it never really slowed down.”

It also paved the way for something that would become another Rush staple: the double live album. All The World’s A Stage (only Rush, or perhaps Peart, would filch the title of their live album from Shakespeare’s As You Like It) was released in September that year to capitalise on the band’s new-found success – not that making a live album had even occurred to the band.

“We hadn’t really thought about it that much at all,” says Lee. “The thing is that management and the record company wanted us to exploit the success of 2112 and keep it going, and live albums were kind of the thing du jour, do you know what I mean? Like a Humble Pie live album had come out and it had done really well, and you know, Kiss were doing a live album.

“All these people started dropping live albums, so they said, ‘You guys have to do a live album as well.’ We hadn’t really thought about it until that point, and then because we were playing three nights at Massey Hall, based on the success of 2112, we thought, ‘Okay, that makes sense – let’s record our homecoming,’ so to speak.”

2112 was an unlikely platform from which to launch a career – they wouldn’t even get to play side one in its entirety until the Test For Echo tour, some 20 years after the album’s release (Lee might announce on All The World’s A Stage, ‘We’d like to play for you side one of our latest album,’ but the band would omit Discovery and Oracle: The Dream).

However, it afforded them the sort of artistic latitude most artists can only dream of, even as Rush moved away from more progressive and expansive pieces and into a more moderate approach to their songwriting (less Moog and bass pedals, more hit singles). That’s until they came to something approaching full circle with the conceptual Clockwork Angels album.

Fans still want to hear the story of the Priests Of The Temples Of Syrinx, and people still place 2112 at the top of fan and critics’ polls alike. Did Lee know the effect the album might have when they sent it out into the world?

“No,” he says with an emphatic shake of the head. “I mean, it’s hard to really know because you can’t be on both sides of the thing. I’ve had a lot of people, you know, some really accomplished musicians come up to me many times since then and say, ‘That record really reached me – there was something that was so different about it.’

“But my sense is that there was a lot of passion in that record, there was a lot of ferocity in that record and it cut through, and it had a sound that was really pretty different from anything else going on at that time. I think it just cut through. You know, cut through the static of all the music that was out there, and it reached people.”

And some 40 years later, it’s still reaching people.

This article originally appeared in Prog 63.