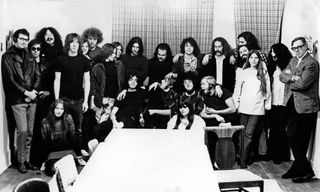

Look inside Please Kill Me, Legs McNeil and Gillian Mc Cain’s brilliant, definitive oral history of punk rock and you’ll see a touching dedication “for his gorgeous taste in music, his generous intellect and his killer sense of humour” to Danny Fields, “forever the coolest guy in the room.” A music industry legend, Fields signed The Stooges and MC5 to Elektra records in 1968, worked as The Doors’ publicist, managed the Ramones and introduced Iggy Pop to David Bowie, operating at the heart of the music business during arguably its most exciting era. “You could make a convincing case that without Danny Fields, punk rock would not have happened,” the New York Times noted in 2014.

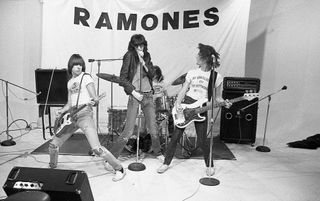

Having previously worked as a journalist, author, disc jockey and record company executive, this month Fields is publishing his first book of photographs, My Ramones, a collection of rare and never before-seen images of the Ramones, taken between 1975 and 1977. TeamRock caught up with Fields in a London book shop, and found the 77-year-old New Yorker engaging company, so much so that a proposed 30 minute interview stretched effortlessly into a two-hour conversation.

“When I was taking pictures of the making of the first Ramones album in 1976 I didn’t think that 40 years later I’d be sitting in London, England talking about photos that I only took in some instances because there was nothing else to do,” says Fields. “But since we’re here…”

Back when you were a teenager, what did you imagine you might do with your life?

Danny Fields: “I never knew. But I knew I wasn’t going to be a doctor like my father, or a dentist like my uncles. I went to Harvard Law School, mainly because Cambridge, Massachusetts was home to the most beautiful people I’d ever seen in my life, but my life only really began when I dropped out.”

Were you always obsessed by music?

“Not particularly. I mean I saw The Beatles perform at Carnegie Hall in 1964, the second concert on their first American tour, but they didn’t really move me, and never have. But when I started working at Datebook magazine, a magazine aimed at teenage girls, there was obviously an interest in the bands from the early ‘English invasion’ – The Beatles, Herman’s Hermits, The Hollies, etc,. My brother was in school in Berkeley [California] and he was a fan of Jefferson Airplane and The Byrds, and he’d send me back singles, so that was more what I was listening to. But my publisher at Datebook had bought Maureen Cleave’s interviews with The Beatles from the Evening Standard, and I thought it might be a good idea to take these interviews and chop them up to use in the magazine. I found a Paul McCartney quote where he described America as “a lousy country where anyone black is a dirty nigger’, and I thought ‘Oh, that looks like a headline to me.’ And then there was another quote from John Lennon saying ‘I don’t know which will go first, rock n’ roll or Christianity’, which I thought was interesting. So I ran maybe 800 words in Datebook from those articles. And deep in there was Lennon’s quote about The Beatles being more popular than Jesus. And then some mother in Alabama read that in her daughter’s magazine, and took it to a local radio station, and some DJ who hated that he’d been forced to play these Beatles records started a crusade in this swampy redneck town encouraging listeners to bring their Beatles records and pictures down to the local church and he’d set them all on fire. And in Bible Belt Jesus America this idea proved rather contagious.”

When did you become aware of the reaction your article had stirred up?

“Well, by then I’d moved to California, but I learned about it from afar, mainly because Datebook had to run articles explaining that they weren’t really agents of Satan, and that The Beatles genuinely said these things. And then because The Beatles were getting death threats from the KKK and whoever, John Lennon was summoned to hold a press conference in Chicago to ask about his Jesus comments – which must have confused him given that he’d given that interview eight months previously and no-one in England cared. After the last concert on that tour, The Beatles announced they would never play again, and they never did. And I thought ‘Hmmm, I wonder how much part my article had in this? What fun to make such mischief!’”

In California you began working as The Doors publicist, but you didn’t get along with Jim Morrison…

“Well, I don’t know a lot of people that did. I mean, [Doors guitarist] Robbie Krieger once told me on the record that he used to wake up shaking, sweating and screaming after having dreams that Morrison was still alive, that possibility was enough to give his bandmates nightmares and needing medication. I thought he was fabulous at first, but then we fell out. I’d gone to see them in San Francisco and I went backstage and he was surrounded by all these ugly girls with greasy hair and I thought ‘Uh, I can’t have a star that attracts such filth, I’ll have to find him a classy girl that complements him!’ And I thought ‘Oh, [Velvet Underground-affiliated singer/model/actress] Nico would like him!’ At the time Nico was living in LA with [Warhol ‘It Girl’] Edie Sedgwick – what a household that was – in a place called The Castle, high in the Hollywood Hills, and I persuaded Morrison to come with me to meet her. Morrison used to consume handfuls of pills and acid, and I remember that night he was incredibly drunk and just kept putting out his hand saying ‘More mescaline!’ He wanted to drive home, and I thought it’d be pretty bad for me to allow my new star to kill himself, so I took his car keys out of the ignition and put them under the mat, which meant that he couldn’t find them. And he never forgave me for that, he hated me from then on, because obviously I’d deprived him of his independence and freedom, and this became me ‘kidnapping’ him. All because I tried to save his ass…so thoughtless!”

So in September 1968 you went to see the MC5 and The Stooges play in Detroit/Ann Arbor, and signed both bands to Elektra that same weekend. In Please Kill Me you said of The Stooges ‘This was the music I’d been waiting to hear my whole life.’ What was it that so captivated you?

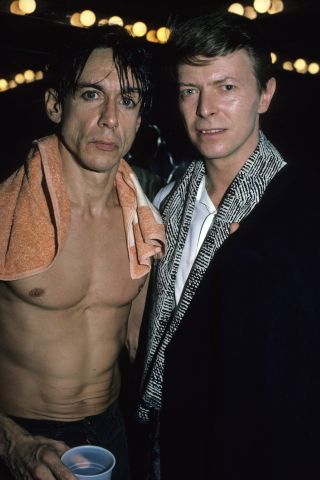

“Well, I was coming up the stairs to this big student auditorium and I heard this music and I was just hooked and drawn in. Once I got into the hall, I saw Iggy, and that was it. This, to me, was rock n’ roll with its own atomic energy, so simple and catchy and powerful. Nothing had ever sounded that good to me. They were an incredible band, but Iggy could be a real handful back then…thank you David Bowie for finally taking him off my hands!”

**You introduced the two of them to one another in New York, right?

** “I did. I remember seeing David mention Iggy in Melody Maker as his new favourite male vocalist, and that stuck in my mind. And then when Iggy and I lived together I got a call from the music writer Lisa Robinson saying ‘I’m at Max’s [infamous New York nightclub Max’s Kansas City] with David Bowie and he wants to meet Iggy: is he still staying with you?’ Iggy had fallen asleep beside me watching TV, so I said ‘Jim [Iggy’s real name] wake up, that guy David Bowie who wrote about you in Melody Maker is around the corner and wants to meet you’ and we walked the five minutes over to Max’s. I introduced them and they started talking about music immediately, and I went over to talk to Lisa, who said they’d just come from meeting Lou Reed for dinner. So yeah, that was the beginning of that partnership. Iggy tells this story differently, but that’s what happened.”

1970s New York still has a really iconic image in music history, and you were right in the middle of it, with the Warhol crowd and ‘faces’ from the emerging punk scene. What did you love most about the city at that time?

“It had such great energy. There was a moment when all the poets and musicians and reporters and painters and hairdressers gravitated towards Max’s because the owner had a lot of great friends from the art and theatre scenes who knew how to enjoy themselves. It’s not like I was waking up thinking ‘Oh, what a fabulous era I’m living in!’ – there was still every day shit to deal with, like my rent might have been overdue, or it might have been a while since I’d got laid – but hindsight allows you to compress the mundane into compacted fabulous memories. What’s that Wordsworth quote… ‘Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive, But to be young was very heaven!’

You were openly ‘out’ at the time, so did New York then seem like a particularly liberated city?

“I was always famously gay, but New York isn’t the Bible Belt, everyone there is kinda a minority in some way. If you lose the gays who’s going to do your hair, who’s going to do your window-dressing? But there was also a very powerful, elite group of intellectual and artistic gay men in New York then, so you never felt any need to be embarrassed or to hide away. I remember once being arrested in this kind of unlicensed, pop-up bar where little faggots like myself would come to dance and drink, and one night the police came and piled about 40 of us into paddy wagons and put us all in one big cell. So we were locked away from the outside world for a night, and had even more of a party! The next morning we were all lined up – a real motley crew, with some guys in Brooks Brothers suits, and others in little vinyl shorts - to appear in front of a judge, charged with ‘Dancing to a jukebox’, and the case was instantly dismissed. Basically someone hadn’t paid off the police to open this bar, but that was the extent of the oppression.”

So, let’s talk about the Ramones…

“Well, the book is called My Ramones, because the photos are all of the four I knew, the original four, who of course are all dead, as of 2014. I can’t imagine doing this while any of them were alive, because I’d have had to consult with them, but on the other hand I was confident that no picture in the book would cause them excessive distress.”

When you first saw them, did you have that same visceral reaction as when you first heard The Stooges?

“Yes. And actually they all loved The Stooges, they’d gather together to listen to those records, the only four people in Queens that knew The Stooges existed. But with the Ramones I could hear the lyrics too, because I was sitting right in front of them at CBGBs, so when Joey sang ‘I don’t wanna go down to the basement’ it was like ‘Woah!’ They sounded great and they looked great and there was no stopping between songs and it was just like the sound was inhabiting your body from top to bottom. At the time I was writing a column for the Soho Weekly News and including artists like Television or Suicide or Patti Smith, and every week the Ramones would ring me up and go ‘We’re better than them! We’re great!’ and I liked that attitude. So I basically went to see them at CBGBs to shut them up and of course I loved them.”

And so did it become your mission then to bring this music to the world?

“Yes. And I thought that maybe finally people might take me seriously. I mean, nothing I’d been involved with had sold millions of records – well, The Doors did, but that was nothing really to do with me – but I’d signed and worked with bands that had great critical success, and people knew I had taste. Seymour Stein’s label had signed Richard Hell and they were looking downtown at other bands, and I knew Linda Stein, his wife, so we took them on together because we thought they were wonderful.”

The images in My Ramones give a great sense of the energy, and in some instances perhaps, the innocence and naivety of the band in those early years.

“Well, obviously the proximity I had to them make these pictures interesting. And I mean, if I took a bad picture it wasn’t going anywhere: I was the manager so I’d just rip it up. I think the images are intimate without being intrusive. A lot of the time they knew that I was taking photos, and y’know, they’re performers, so if there was a certain mood they knew how to enhance it a little. The photographs are often kinda ‘posed candids’, which makes them different from either posed or candid shots.”

It’s 40 years since Ramones first played in London, gigs which famously helped inspire the birth of the punk scene in the UK. What do you remember now of that trip?

“Well, it’s now seen as this big iconic, historical thing, but it didn’t feel legendary at the time. But it was astonishing in that, when Ramones played the Roundhouse [supporting The Flaming Groovies on July 4, 1976], there were more people there than they had ever cumulatively played to in their career at that point. I mean, most of my work before that with them was getting them ‘jobs’ – Johnny always called them ‘jobs’, not gigs – and here we were in one of the world’s most important cities and there were thousands of people there, and people being turned away. We arrived on the Friday morning, played the Roundhouse, played Dingwalls the next night and were gone, but apparently that visit lit the torch-paper for punk over here. I know The Clash played their first show in Sheffield on July 4, with the Pistols, so they missed the Roundhouse show but came down for the Dingwalls show and I remember Johnny Ramone and [Clash bassist] Paul Simenon talking beforehand. Paul said ‘We played our first show last night: no-one wants us because we don’t know what we’re doing, and we’re not good enough’ and Johnny said ‘Wait, you haven’t seen play. We stink! We can’t play! Just do what we do… just play!’ But I remember Joe Strummer saying later ‘You couldn’t slide a cigarette paper between any two of their songs’ so I guess people were impressed. Plus, those gigs showed promoters that there was an audience for punk, and that was important too.”

You parted company with Ramones after five years: why did they fire you?

“Well, they didn’t really fire me as such: we signed a five year contract and at the end of that it was up to both parties to sign another one, and they felt that they weren’t selling enough records – which they weren’t, and never did – so they felt it was time to make a change. And all I could say was ‘Good luck.’ I never got rich with the Ramones, but I had fun experiences. They originally thought that their songs were so good that they’d sell five million copies of their first album, and then be able to retire rich, and never have to bother with one another again. But it didn’t happen that way.”

When you heard the song Danny Says for the first time, after you parted company with the band, were you quite touched?

“Hmmm, no, because it’s not about me. It was originally called Tommy Says, because Tommy Ramone was the de facto manager at the start and he was calling the shots, and Joey wrote it as a kind of love letter/apology to his girlfriend, because he was always having to leave her…and then famously she left him for Johnny. And you know, it’s nice, it’s a sweet song: I don’t mean to sound sexist, but it’s every girl’s favourite Ramones song. But I never booked the Ramones in Idaho.”

The forthcoming film about your life is also called Danny Says: are you happy with how it turned out?

“Well, I had nothing to do with it, except for giving the film-makers permission to go through my filing cabinets and my Rolodex. I saw it once, because it was being premiered at the SXSW festival in Texas last year, and I figured that I should see it beforehand, just in case I was going to have to kill myself afterwards. But I think they did a really good job. They’re screening it at the British Library on July 4, when I’m doing a talk with [music writer] Barney Hoskyns, so if anyone wants to see it, that’s your chance.”

You’ve had a really interesting life, and been involved with so many legendary artists, so what’s on the bucket list now for you?

“I don’t know. I hope to keep travelling and meeting people and having adventures. Every time I open a newspaper now someone else I know is dropping dead, so I’m just happy to be out here, making new friends. It’s not been a bad life.”