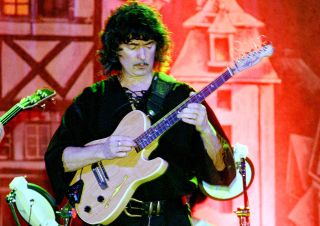

Twenty-one years ago, in September 1995, I spent four boozy and relaxed hours in the company of Ritchie Blackmore at the now closed Normandie Inn in Bohemia, Long Island – his supposedly haunted home-from-home about an hour’s drive north of New York City. He was good company; honest, amusing, dry as toast. And never the moody sod as he is so often portrayed.

Nearly two years after he’d quit Deep Purple for the third and final time, it soon emerged that he was still immensely relieved to never have to work with Ian Gillan again. Such personality clashes aside, Blackmore looked back over his lengthy career revealing a tormented soul. Clearly confident in his abilities as guitarist, paradoxically he seemed unaware of his strengths and weaknesses as a songwriter.

Our rambling conversation filled four cassette tapes, the last of which was hastily purloined from behind the bar – The Best Of Englebert Humperdink. Over this, Blackmore talked finally about “finding it harder and harder to be inspired by just playing loud”, and moving on to what he described as his “private music” – the medieval-inspired acoustic folk which would be his next project. I presumed it might be the beer talking. Certainly it was the last thing I would have predicted he’d spend the next 21 years recording and touring, mainly acoustically, alongside his now-wife Candice Night in Blackmore’s Night.

What nobody – perhaps not even he – knew then was that the Rainbow album he was just about to tour with, Stranger In Us All, would be his last hard rock venture. Until now. But before we got to Rainbow, we went all way back to the beginning…

Chris Curtis, the drummer with The Searchers, came up with the idea for Roundabout, the band that would be renamed Deep Purple, in ’67. But it took you a year to commit. Why?

I was waiting to join but nothing happened. I was in Hamburg, and had played with The Searchers in sixty-three, and remained friends with Chris Curtis. When he wanted to put a band together he sent me all these telegrams and called me over. I came over, and – he was very animated and very theatrical. I asked him: “Who’s in the band? What’s the deal?” And he would go: “The best guitarist in the world is you. You’re in the band. You’ll be playing second guitar”. “So you’ll be playing lead, right? Who will be playing drums?” “I’ll be playing drums. Jon Lord will be playing organ.” It was going to be called The Light. And then he said: “And I will be playing bass and doing vocals.” So he was doing lead guitar, drums, bass and vocals! So when I saw Jon, I said: “What’s going on? Is he a bit…?” [makes circular motion by his temple with his index finger].

So after a while, we were playing together at this little house in South Kensington. But Chris was saying such ridiculous things. He was so ludicrous with what he wanted to do. We were gonna be called The Light, initially, and whoever the biggest band was at the time – I think it was Clapton and The Cream – were going to be opening for us. He was nuts! The second time I went there the house looked like it had actually been hit by a bomb – no furniture and carpets, just rubble! Someone had gone in with a pneumatic drill and drilled up everything, plaster was down everywhere. Then I saw some of the plaster move. It was Chris, who was sleeping on the floor. “Ah, Ritchie, come on in. The band’s great, it’s all happening”. He was just full of bullshit.

According to Jon Lord, the name Deep Purple came from your grandmother’s favourite song.

Close. It was a song my grandmother used to play on the piano.

Was your grandmother a professional musician?

No, she just tinkered around on the piano. But she used to play Deep Purple.

Where did the name Rainbow come from?

It came from the Hollywood Bar & Grill (aka the Rainbow on LA’s Sunset Strip). I was in there with Ronnie [James Dio] getting drunk as usual and said: “What shall we call the band?” and just pointed to the sign.

Lucky you weren’t in the Pheasant and Firkin.

Or the Bull And Bush. Or all the other transvestite bars we used to go to.

It was your idea to split the first line-up, Deep Purple Mark I. But Episode Six drummer Mick Underwood, who you played with in The Outlaws, recommended you get in Episode Six’s singer, lan Gillan.

That’s right. I said to Mick: “We’re looking for a singer. Do you know anybody?” And he said: “Well, you can use our singer if you like. We’re breaking up.” That’s how we got lan Gillan. Gillan could scream. He had a really good voice then.

Original Purple bassist Nick Simper said he was very upset that none of you told him to his face that he was out of the band.

Nobody wants to jump on the phone and go: “Hey, you’re fired!” That, really, to me, is management’s job. They don’t do fucking much! I think the least they can do is to try and buffer the band from each other if there’s a problem. Usually I’ve found with managers that the last thing they want to do is spread the bad news. They want all the good news – and to be paid commission on it – but they don’t want to do the hard work.

The first album you released with Ian Gillan was Concerto For Group And Orchestra in 1969. Jon Lord said you got upset because it diverted the focus of attention in the band to him from you.

That’s true. We were a rock band. I couldn’t understand why we kept playing with orchestras. It started to get up my nose. The first thing was a novelty, a band playing with an orchestra. I didn’t think it was particularly good but we pulled it off. Then Jon wrote another one [Gemini Suite], and they wanted us to do it again. I went: “No, no. I’m not getting involved again. I’m in a rock’n’roll band.” I said: “Jon, we should make a rock’n’roll record for people in parties. It should be non-stop, hard-hitting rock’n’roll.” I was impressed with what Zeppelin did, and I wanted to do that kind of stuff, and if it doesn’t take off we’ll go and play with orchestras the rest of our lives. So we did it, and it was Deep Purple In Rock, which, luckily, took off. We’d purposely made it so it hammered along every song, there was no lull. I was very pleased with it because I never wanted to work with an orchestra again.

Which is odd, because you are very influenced by the classics. You went on to use strings on Rainbow’s Stargazer.

Which I was very pleased with, incidentally. That was very exciting. When I first thought of the idea, I thought: “Nah, could be a bit corny.” But the more I got into it, playing with the band, I thought this could sound really good if it’s done properly. And I’m very pleased with that.

In Purple, were you keen to be seen as the leader?

Not so much keen to be seen, I just had my own set ideas. It was passion. I didn’t want to be awkward. I just really felt it should work. I was like: “C’mon, lads!” I felt the rest of the band weren’t so passionate. But it was a passion that fell by the wayside. I have other passions now. To talk about Deep Purple… I’m very thankful that I can live a certain way now, but I don’t think the band towards the end was very truthful. I don’t think they were in it for the right reason.

Bassist Roger Glover mentioned how you all wrote Black Night – you came back from the pub drunk, having been told to write a single.

Very true. That’s a very nice memory. We went down the pub in Holborn. The management came in – it was the like Leggy Mountbatten thing from The Rutles – “Lads! You need a hit!” We were drinking, so we went back. I knocked out the Ricky Nelson Summertime bass riff, which we did as a shuffle. We just added a couple of bits that worked very well. And all of a sudden it was number two.

lan Gillan was clearly the guy you wanted in I969. You asked him to join Rainbow again in I980. You worked with him again in I984 when Deep Purple Mark II re-formed. Yet the pair of you can’t tolerate each other.

I used to call him Oliver Rude, because he is very similar to Oliver Reed. He’s a very brash individual. It wasn’t just the voice. I found him very disquieting to be around. A roadie would call us up and say: “If you’re thinking about going for a drink in the hotel, I just thought I’d tell you Gillan’s in the bar.” I’d say: “Is it hunched shoulders?” And if he said yes, that meant that lan had been in there all day and night, and just wanted to blow off steam to someone. If you walked in and he saw you, he’d sit up and go: “Hey!” But I’d be like [slumps into depression]: “All right? But, er, I’ve got to go now.”

Didn’t Mick Underwood warn you: “He’s a great singer, but…”?

No. I remember him saying he didn’t like him as a person because he’d said he’d lost his voice and couldn’t carry on the band, but the next thing we know he’s got a band together with you lot. You’ve got to know lan to figure out what his personality is. He’s got this very strange side to him which is another side I don’t like, the obnoxious side, and that doesn’t often come out until you’ve been around him quite often. Because he’s got the flattering side, the very charming side that some people see. He an intelligent man. But he just used to be so coarse. I didn’t like to be around the guy because I felt that he was doing things for shock value, to be talked about, for the hell of it.

Jon Lord said when Gillan and Roger Glover were going to leave, the first he knew of it was when you told him you wanted a bluesier singer and a bassist that could sing harmonies.

That’s true. That’s what did happen. [Long pause] I’m a good little devil [laughs]. But I hadn’t ‘decided’, I had gone: “Come on, we’ve got to do something.” And it was always like: “Okay, you’re right. What?” I remember with Roger; I didn’t want to get rid of him, I wanted to leave. I said: “Paicey, we’re leaving!” Cos I wanted to form this thing with Phil Lynott [a trio called Baby Face]. But Paicey was reluctant to leave: “Phil’s good, but don’t you think we should try… Ian” I said: “No, I can’t handle Gillan.”

- Deep Purple release behind-the-scenes Jon Lord Concerto clip

- Iron Maiden’s 10 Most Epic Songs

- Will Ritchie's Rainbow rise... or plummet down to Earth?

- The Top 10 greatest Ritchie Blackmore songs

You left before Purple’s final seventies album, Come Taste The Band. Glenn Hughes quoted you as saying: “I didn’t want to play any of that shoeshine music.”

Very true.

That sounds kind of racist…

Yeah, I’m a racist [laughs].

Are you against black music, or black people?

Jimi Hendrix taught me an awful lot, and black blues players. But I don’t like black R&B music, I don’t like disco. But Glenn was not being himself. He wanted to be Stevie Wonder. He is a natural musician. I always liked him as a person, he was a very nice guy. But I always preferred Coverdale’s voice. I didn’t like the high range that Glenn had.

Many stories say that you recommended Tommy Bolin as your replacement. Is that true?

I didn’t recommend Tommy Bolin. I was aware of him, and I think someone asked me about him and I said: “Oh, he’s really good.” But like this last time [November 1993], when I wanted to leave, I didn’t just want to go and sink their ship, I wanted them to have time to find someone else. I think it was Coverdale who found him.

Did you ever see the band with Tommy?

No.

Rainbow came out of your disenchantment with Mark III. When it came to recording their debut album, Ritchie Blackmore’s Rainbow, you used members of the band Elf, including singer Ronnie Dio. But a different line-up backed you on Rainbow’s debut tour. Did you ever intend to tour with that band?

I did. Until we got to rehearsals and I realised how bad it would be. In the studio they made it – except for Gary [Driscoll, drummer]. He had a tendency of losing the tempo, then catching up. We’d start playing, and I’d watch him and his headphones would slowly slide off and he’d slowly lose the tempo. So after four takes we would have to tape them to his head. He was so nervous. Once he counted one, two, three, four, and everybody came in – except for him! [laughs]. But he was such a nice guy. I’ve got this thing with drummers if they can’t keep time.

Perhaps you’ve been spoilt with Ian Paice.

Yeah, he’s a great drummer.

Most people think Rainbow Rising is the best album Rainbow made.

At that point, yeah.

But not now?

Oh no, no. The best Rainbow album I have made, without a doubt, is this one [1995’s Stranger In Us All]. Without a doubt. Now people will say: “Oh, but he would say that.” But not me, I wouldn’t. The best one I’ve made is this one. I liked a couple of others: Straight Between The Eyes and Difficult To Cure in there too. Stargazer was very good, but the rest of the album was very extremely average.

Did you really set fire to Rainbow bassist Jimmy Bain’s bed while he was still in it?

Yeah. But I told him.

You mean you woke him up?

No. He had some girl on the bed with him. I set fire to something and put it by his bed, and it started catching the bedclothes. I thought he’d pick it up and put it out. But he didn’t see it. So I’m there watching these flames, going: “Er, Jimmy…” “Fucking hell! The bed’s on fire!” So he grabbed the bedclothes and threw them out of the window. But when it hit the ground it hit the Astroturf and set that ablaze too.

Long Live Rock ‘N’ Roll was the last album you made with Ronnie Dio. Did you fall out with him afterwards, or before?

I was always very close to Ronnie until, to be quite honest, he met up with Wendy [Dio’s future wife and manager], then it got very strained. She was a nice enough woman, but we didn’t really click. I remember being at the Chateau [the Chateau d’Herouville near Paris, dubbed the Honky Chateau studio by Elton John] when we were trying to sort out a song. I was playing an effect, trying to get the song down, and both of them walked by and one of them said: “We want to talk to you.” Ronnie said. “I’ve just heard from Wendy that you’re on the front page of Circus and we’re not.” “Really? I had no idea.” The three of us had done the photo session, but the photographer did a couple of me on my own, and one of these got on the cover. And Cozy [Powell, drummer] or Ronnie said: “If we’re gonna be your fucking sidekicks then we’ll act accordingly.” That really pissed me off, cos that was nothing to do with me. After that it went downhill, cos I had no respect for either of them after that.

So you got disillusioned with Ronnie after that episode and that album?

Yeah, that didn’t do any favours for me. I didn’t like that. Because he was so nasty about it. “We’re not on the front cover with you!” Is that my fault? I lost a lot of respect. I always remember the good times. It was just that one thing that turned me right off. Great singer and a very funny man.

For the next Rainbow album, Down To Earth, you asked Roger Glover back.

As a producer, yeah. But we didn’t have a bass player, so he started playing the bass.

Roger said he thought that was your way of admitting that you were wrong in 1973.

[Laughs] Really? I never thought of it quite like that. But on the other hand the manager talked to me and said Roger’s a good producer. But I never thought of him as a bass player.

Cozy Powell said that when he first joined the band you were driven and had a point to prove, but after a while he watched you go cold and lose your ambition, your anger. Is that true?

Yeah. You can’t be angry all the time or you’d go nuts.

But you seem to be fired up whenever you get a new line-up, and do your best work when you’ve just had a change.

That’s right. When I get the new blood. It’s a lot of that, plus what’s happened before.

The second Deep Purple MK II album, Machine Head, kind of shoots that theory down. Why was that such a peak?

That is my favourite LP with Purple. It came after Fireball, which I thought was a complete flop, disastrous.

Why was Fireball so bad? Were you not really involved with it?

Yeah, I was. There was just nothing on it worthwhile talking about. I can’t even remember any of the songs.

Demon’s Eye, No No No…

Demon’s Eye was like a riff; Farmer’s Daughter was a spoof on country and western; No No No, to me, was bordering on banal. People liked the track Fireball, but that was just fast with a double bass drum. And an air-conditioning unit.

Ronnie was replaced by Graham Bonnett for the Down To Earth album. Was that Rainbow’s best-selling record?

Since You Been Gone did very well because it was written by Russ Ballard. There’s an interesting story there – and now I’m bashing Cozy. I remember when Since You Been Gone came up, the management said: “What do you think of that?” And I said: “It’s a great idea. Let’s do it.” It had just been done by another band called Clout. But when we went to do it, Cozy was going: “I don’t like this song.” We did it once, then when we went to do it again his famous quote was: “I am going to play this but one more time!” He hated the song. So we did it, and Roger went: “That was good, but let’s do one more take”. And Cozy went: “No! I fucking hate that song! It’s bullshit! I don’t want anything to do with it!” So Roger said he thought he could manipulate it with effects, and he did. When it was like number two or three in the charts, I heard from someone who went up to Cozy and said: “Oh, I love Since You’ve Been Gone,” Cozy had said: “Yeah, that’s one of my favourite tracks.” Isn’t that interesting?

What happened with Graham Bonnet? Why did he leave? Was it the whistling and Percy Thrower impersonations?

Fucking hell, Graham… Roger always had a good thing for him, although Roger used to say: “God said I will give you a wonderful voice – but I will take away everything else.” Graham was a nice enough guy, just completely… lost. One day I said to him: “How are you feeling?” “Oh, not too good. I feel kind of fuzzy”. Someone said: “Have you eaten?” “That’s it – I’m fucking hungry!” He had literally forgotten to eat for ages! And all these singers used to say I was a mental case.

You asked Ian Gillan to join Rainbow around Christmas 1981, didn’t you?

I think I did. I went round his house and knocked on the door. “Ian!” “Fucking hell! Come in!” We were like the best of friends, you know? So I went in and said: “I came round to see if you wanted to join Rainbow?” We started drinking a full bottle of vodka. But before I got halfway through the bottle I was thinking to myself: “I’m not so sure this is a good idea.” By the time we’d finished the vodka I was like [puts his hands together in prayer], “I hope he doesn’t say yes!” So he says: “Rich, I don’t know if I can. I’m going to have to let you know.” “Yeah, okay Ian. Great seeing you again.” Phew! Let’s get out of here!

What made you do it?

I don’t know. I’d just forgotten what he was like. But when I met up with him again I thought: “Oh, it’s all coming back.” But he turned it down, so it lies with him. Had he said yes I would’ve gone: “Oh, shit. Now what am I going to do?”

You got Joe Lynn Turner instead.

Joe was the best singer we had in Rainbow, without a doubt. Him singing things like: Can’t Let You Go, Street Of Dreams, he was brilliant. On his ballads no one could touch him, and his was the voice I was looking for. And when we broke up and I had to do the Purple thing – I shouldn’t have really done that, but I did it because it was basically easy money. The money was dangled in front of me and I thought, well, the Rainbow thing’s going well but, shit, okay. Gillan came along and talked us into it. I thought we’d do maybe one LP, but then it got to be more than one. But looking back, I probably should have stayed with Rainbow, because Joe was singing really well. He pissed me off on stage because he was like Judy Garland. I could not stop his little twee movements. “Joe! Don’t do that crap!” I threatened him backstage at Leeds. I grabbed him and said: If you do any more of those pansy movements I’m gonna fucking nail you!”

When Deep Purple re-formed in I984, you made a video that showed the band getting together for the first time in Vermont. Was that footage staged or real?

It depends.

The bit I’m referring to in particular is when you walk in and shake hands with the guys, and hold your hand out to Ian last then pretend to withdraw it at the last moment.

Do I? I’ve had some good times with Gillan, too. I often blame myself for him. He tells this story too. We were in the Rock ‘N’ Roll Circus in France, a club, in I970. We were in this big club, and he went to sit down. I saw he was a bit drunk, so I pulled the chair away so he would miss. But what I didn’t realise was that behind us was a big drop of about fifteen feet. And he fell down this drop and crunched his head. I heard his head go [thumps the table hard] on the stone floor. I’m going: “Oh no! He’s split his head open.” After that he was never the same. He did change.

So it was the blow on the head, rather than the fact that he resented you for doing that to him?

It was the blow. I thought he was out cold – and he was a strong guy. I thought he was dead. But then he got back up, and I go: “Are you all right?” And he goes: “Yeah, I just hurt my head a bit.” But he hit his head on the concrete.

Are you really saying that the feud between you and Ian is all because of a blow to his head, that you caused?

That’s right!

Some of your best tracks have been those on which, at least in part, you used an acoustic guitar – Catch The Rainbow, Temple Of The King, Sixteenth Century Greensleeves, Soldier Of Fortune – but you haven’t used one very often. Is it more difficult to play?

No, not at all. Easier, actually. But it doesn’t translate to live because you’re relying on some guy to bring you up, and those monitors are crazy. But my next LP will be all acoustic – although that’s a different type of music. I have eight songs that I’m doing in a medieval folk-type vein. That’s with my girlfriend singing. We play it to our friends in the bar at home. I’ll see how the Rainbow thing goes, depending on whether people want to hear any more Rainbow. I’ll leave it up to the audience. If they don’t want to hear any more I’ll knock it on the head. I’m very excited about this next project because it’s completely different from the hard rock thing.

You’ve been talking about that for a long time.

Yes, but I have to move gradually. I like to know exactly what I’m doing before I get into a thing. But now I’m ready to change. I think this might be my last LP as an out-and-out rock player. I might come back to it in a few years, it depends. But I’m finding it harder and harder to be inspired by just playing loud. I’d rather just sit down with a guitar and play. This whole ‘You’ve got to hit with a big riff’ thing is beginning to wear off. It’s been thirty years, you know?

What ’s the last thing you heard that moved you?

ABBA. And I heard some German friends of mine playing 1600s music on mandolins and old instruments. But recently, nothing. I don’t live today, I really don’t. I don’t want to know about what’s going on. [Laughs] I’d rather be a painter than be involved in it.

Where do you think Ritchie Blackmore stands in the great parade of guitarists?

As a guitar player? Um, I think I’m very good, when I’m at home, but I don’t really put too much down on tape. But there are very many great guitar players out there, technically better than I am. I do have a ‘stamp’, and I’m very happy now not to be among the top guns. In the eighties I felt like I had to be the fastest gun.

When you were winning so many of the polls?

Yeah. Then it was Eddie Van Halen. And I noticed that eventually Eddie couldn’t stand it any longer, and started playing the organ. But that fast style of guitar playing is not for me any more. I don’t listen to it. I mean, I wouldn’t buy an LP anyway, but when I hear something on the radio I think: “Wow, that guy’s fast.” Like Joe Satriani – this guy really knows how to run around. But then I hear people like BB King and think: “This guy plays from the heart… but I wish he’d play more than those three notes, and a bit faster [laughs].”

Do you think your guitar playing abilities have been generally appreciated? People often talk about Page, Clapton and Beck, but your name is not usually mentioned in that company.

Jeff Beck is always my favourite. He doesn’t have to run around. He plays a note and I think: “Where did he find that? It’s not on my guitar!” I’ve always loved Jeff, and I love his attitude: “Am I a guitar player? No, I’d rather fix a car.” And that’s true. He doesn’t jump up and down, he doesn’t show off the latest fashion. He just stays as he is. He always looks the same, wears the same T-shirt; doesn’t pander to fashion, wear shorts, or long shorts, doesn’t spit. He’s just always there, and has been since 1964.

But don’t you think you deserve to be mentioned in that kind of company?

I hear that a lot. But Jeff’s done a helluva lot. Page has done an awful lot. He got very famous with Led Zeppelin – he wouldn’t be spoken about so highly if it wasn’t for Led Zeppelin.

But that’s fair if he created them.

Yeah. I wasn’t a fan of theirs particularly, but I did respect them, what they did in the sixties. It wouldn’t happen today. What the fuck is this grunge thing? Why are record companies signing this stuff? I think they are being intimidated.

What’s your biggest regret?

I’d have to really think about that… Um, I don’t really have any regrets.

How would you like to be remembered, then?

I’m not really interested in being remembered. When I go, hopefully I’ll go on to other things. I won’t be looking back. My hobby is a living. I have to tell myself that sometimes, because I get a little bitter about what sells today. I have to remind myself, just keep playing the guitar, don’t knock it. I just get so angry, because I know how many good musicians there are out there. Music is so derivative. Everything I do has been done before.

Roger Glover said that he thought you were one of the people that God had pointed a finger at and given you something that nobody else would have, but that you can’t deal with that talent.

I practise a lot. But only about ten per cent of what I have done is me; ninety per cent of it is very contrived. Only about ten per cent is pure. It’s like when you hear a joke – it only works once. If you’re told a joke, you can’t then ask to hear it again and say: “Could you do it slower, and this time would you walk over to the door when you say the punchline?” I always play my stuff before I come to put it on tape. You can’t turn it on or off. And that’s why I get so angry if people around me aren’t doing their job while I am. If the sound guy is getting it wrong, or the singer, or whatever. And that always comes across as me being moody.

But aren’t you your own worst critic? Like when you upset people because you choose not to play an encore?

If I don’t play an encore it’s usually for one of two reasons: either because I feel that I haven’t played well, or I think the audience wasn’t into it. They just stand there and go: [claps apathetically] “Now come back and do Smoke On The Water.” So I don’t. But I can’t just turn it on. Roger used to say: ‘Well, why don’t you just play it live?” And I’d say: “I can’t play live if you’re going to record the drums twenty times. I agree, but just do one take. I can’t do it twenty times just so you can get a perfect paradiddle.” By then I’ve lost it. Live has to be one take, I can handle that. Paicey couldn’t. He was always going: “Let’s do it again.” Jon and I would just walk out and go to dinner. “We’ve done it fifteen times, and we’re not doing it any more despite what Ian Paice says!”

Last question. What would you like to be written on your tombstone?

[Long pause] There must be some funny answer I can come up with…

That was the plan, yes.

[Another pause before an earnest reply] ‘This man has gone to his grave still wondering what the hell it was all about’. Because I would. I would go to my grave thinking: “Why has this happened? What the hell was that?”

Blackmore on… Seances

“People say seances are evil. But it’s just communication.”

“I get into these events that I can’t even explain. I’ve heard things and witnessed things that are so strange. [Laughs] And the joke is, you try and tell someone else and they won’t believe you. They’ll go: “No, that didn’t happen”. And, in a way, maybe it didn’t happen because we’re not ready to understand it. I don’t understand it but I’m ready for it. I can’t do it justice; I can’t explain what just happened. I know something just happened that is unbelievable. But it’s almost like, well, you’re one of the chosen few because you try and tell someone what you’ve just witnessed and they won’t believe you.

“People are so afraid of seances that they just say they are evil. But it’s just communication. It strikes me that it’s just like being back five hundred years. Imagine if, in the days of King Henry VIll, in his court, he suddenly picked up a phone and went: “Hello George.” They’d all be going: “The devil is speaking to him on that apparatus.”

“Timing is so weird. If you take away time and space, all you’re left with is complete chaos. No facts, no logic is going to work, because time was invented by man. So what’s going on? It’s now been proved that you can go backwards as well as forwards. What does that mean? That we’re running parallel with another life, other lives, billions of lives?

“Certain seances I do ask questions, and the answers I get mean another realm, another part of my brain, can start opening up.

“There was a time when I was compiling a book, keeping a log – I’d been doing it for years. It’s amazing, communication with other… I’m a great believer in: This is not it. This is too shallow.’”

Blackmore on… Led Zeppelin

“John Bonham loved confrontation. And I gave it to him.”

“I used to be very friendly with Bonzo from Led Zeppelin. We’d be sitting drinking in the Rainbow [bar in LA] – and he’d be really up and drunk or really depressed – and he’d be looking at the table. And he used to say to me: ‘It must be really hard to stand there and go: ’der-der-derr, der-der, de-derr’ [Smoke On The Water]. ‘Yeah, it’s nearly as difficult as going: ‘duh-der duh-der dum’ [Whole Lotta Love]. At least we don’t copy anybody!’ He goes: ‘What are you talking about? That’s bullshit!

I know exactly where you got “duh-der duh-der dum” from; you got it from Hey Joe, you just put it to a rhythm.’ And he’s thinking. ‘And Immigrant Song was Little Miss Lover.’ ‘What are you talking about?’ ‘Bom-bobba-didom ba-bom bobbadidom…’ He was not a happy man, but he started it.

“We then went upstairs to the toilet. We’re both there, weeing away, and he says: ‘Rich, did you mean all that?’ I said: ‘No, not really, I was just having a go back at you.’ He says: ‘Oh. I didn’t mean it either. There’s room at the top for everybody.’ So we carried on weeing, then went downstairs and started drinking again.

“But he loved it. He was the kind of guy who liked confrontation, and I would always give it to him. But I always remember when he said how we’d taken bits and pieces from people, so I told him where he got his stuff from. It was interesting to see how his mind was going: ‘Pagey, you bastard. Now I know!’

“They were good days. I had some very funny times with John Bonham, and Keith Moon too. I was living in LA, Keith used to come up to the house all the time. I used to supply the people, and he would supply the goods.”