On July 5 1969, Brian Jones almost knocked Greg Lake unconscious. It was the day The Rolling Stones played a free concert in London’s Hyde Park. Footage from the show appears in most 60s music documentaries: usually Mick Jagger in his white smock reciting Shelley’s Adonais (“Peace, ’e is not dead, ’e does not sleep…”) before the Stones’ roadies release hundreds of butterflies as a tribute to recently deceased ex-guitarist Brian Jones.

What you rarely see is film of the Stones’ opening act, King Crimson. As the afternoon sun glinted off the hairy, tie-dyed audience, Crimson preached musical fire and brimstone. ‘Cat’s foot, iron claw, neuro-surgeons scream for more…’ sang Greg Lake on 21st Century Schizoid Man.

Perched on the side of the stage was a huge mounted photograph of Brian Jones. And at some point during King Crimson’s performance it toppled over. Eyewitnesses recall it almost felled Greg Lake. It was as if blues purist Jones was staging a protest from beyond the grave. After all, Crimson’s clubfooted rhythms and Robert Fripp’s atonal guitar solos were a long way from Chuck Berry’s Come On.

This new music wasn’t blues, it wasn’t folk, it wasn’t pop; it was closer to jazz or classical. But it wasn’t those either. It was Mahler meets Bartók meets Ornette Coleman meets The Beatles’ Helter Skelter… meets, who knows? Where did this music come from?

Pop underwent a seismic change between 1967 and ’69. And the root cause was psychedelia: music inspired by art, poetry, jazz, India, classical music – and drugs, lots of drugs. Psychedelia was progressive rock’s birth mother: it gestated and nurtured this strange new music.

Progressive rock’s first stirrings were detectable in July 1965 and Bob Dylan’s Like A Rolling Stone. It was a six-minute single (twice the length of the average 45) with lyrics that promised some indefinable but profound truth.

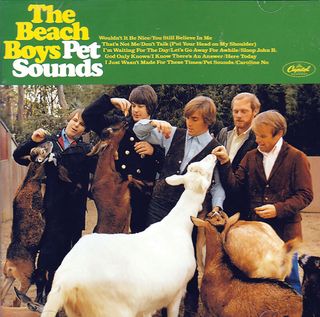

There was more to follow. The Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds album, with its Theramins, bicycle bells and barking dogs, arrived the following May. Three months later, The Beatles responded with the multi-layered Revolver, and George Harrison’s sitar on Tomorrow Never Knows. In December came The Who’s A Quick One, which included what composer Pete Townshend called “a mini rock opera”.

These giant musical steps weren’t just happening at 33rpm. Between February and October ’66, London R&B hopefuls The Yardbirds released three magnificent singles – Shapes Of Things, Over Under Sideways Down and Happenings Ten Years Time Ago – that brought air-raid siren guitar solos and Eastern rhythms into the Top 50.

These new records borrowed from jazz, musique concrète, Indian ragas, even old-English music hall. Barely a year earlier, pop music had been the soundtrack for dancing, fighting, falling in love or having sex. Now, for better or worse, it was making its audience think.

Social change played a part in this evolution. Ringo Starr still credits the abolition of national service in 1963 for allowing The Beatles to thrive.

“I missed the call up by 10 months,” he said, “and so we were allowed, as teenagers, not to be regimented and to turn into these musicians.”

These unregimented teenagers now enjoyed greater freedom and comfort than their parents, who’d been bombed by the Luftwaffe and withstood years of rationing. With this new freedom came choice. The early 60s saw a boom in students enrolling at art schools. Pete Townshend, John Lennon and Ray Davies were just some of the musicians who later brought elements of a freethinking art school education into their music.

But although social change and greater opportunities were important, another key ingredient was drugs. Amphetamines and cannabis had greased the wheels of the music industry since before the Second World War. But the impact of the hallucinogenic Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (aka LSD or ‘acid’) turned pop music upside down and inside out. Even groups who never touched the stuff started making music that sounded like they did.

“I put my hand up, I tried LSD,” says The Moody Blues guitarist Justin Hayward now. Hayward joined the band in 1966 and helped engender their move away from R&B to art rock. He took an acid trip with all bar one of his bandmates. “John [Lodge, bassist] didn’t do it, but the rest of us did. We sat there holding hands. I found the culture around LSD profoundly interesting.”

London’s ‘in-crowd’ comprised just a couple of hundred musicians, artists and filmmakers. But they were soon dictating the agenda.

It was 1967, a time of new ideas in art, music, fashion and literature. For Justin Hayward, the year was all about, “‘Head’ magazines, like International Times, Aldous Huxley’s The Doors Of Perception and Timothy Leary.” Leary was an American psychology lecturer who’d become an LSD evangelist. The Moody Blues later recorded a song, Legend Of A Mind, in his honour.

LSD wasn’t a new drug. It had been discovered by accident by a Swiss chemist in 1938, and had been used, controversially, on some psychiatric patients since the 1940s. Leary had taken his first trip with an old Etonian named Michael Hollingshead, who was living in New York.

The pair hatched a plan: to preach the ‘psychedelic gospel’ (the word ‘psychedelia’ was coined by the psychiatrist and LSD advocate Dr Humphry Osmond). They wanted to turn the world onto LSD, believing it would bring global enlightenment and help end wars.

In 1965, Hollingshead returned to London with a mayonnaise jar containing enough LSD for 5,000 trips. With the help of two fellow Etonians, he established the World Psychedelic Centre in a flat in Pont Street, Chelsea. The apartment soon became a rendezvous for pop stars, actors, poets and thrill-seeking aristocrats wanting to – in the parlance of the day – free their minds.

Paul McCartney, Donovan, Roman Polanski and the then-director of the Tate Gallery, Sir Roland Penrose, were among Hollingshead’s guests. Social boundaries were already blurring; a shared drug experience blurred them further.

The World Psychedelic Centre survived until Hollingshead was busted for cannabis possession in April ’66. But by then, cultural tastemakers on both sides of the world had sampled LSD, and were drip-feeding it into the arts.

To the ordinary man and woman on the street, however, recreational drugs were still something only written about in hysterical newspaper headlines. Many of those who bought The Beatles’ February ’67 single Strawberry Fields Forever wouldn’t have known its shimmering drones mimicked the rush of an oncoming trip. But other musicians knew.

“Strawberry Fields… was utterly bizarre, creative, strange and different,” enthused fellow LSD convert Pete Townshend, who’d became a regular at UFO, a newly opened club on London’s Tottenham Court Road, where everyone – band and audience – looked as if they might be tripping.

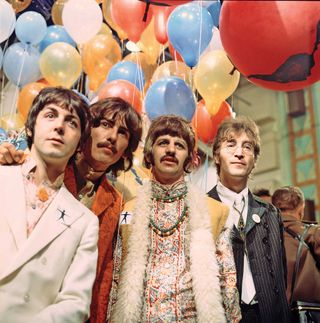

Four months after Strawberry Fields…, The Beatles released Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, and, as Justin Hayward puts it, “the whole world changed.” Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds and A Day In The Life were pop music reimagined through the prism of LSD, Abbey Road’s state-of-the-art studios and The Beatles’ boundless imagination. Pop music could now be whatever it wanted to be.

“I found Sgt Pepper almost disturbing,” says 10cc’s Kevin Godley, a student at Stoke-on-Trent art college at the time. “It was so strange it was almost alien. On the day it came out, everyone in college stopped working and was listening. There was a different song playing in every room. Everything changed. It was like the first iPhone. Okay, it was just a phone before, but now it’s this.”

“We knew Sgt Pepper was coming, but it still opened all the doors,” says Justin Hayward. The Moody Blues were recording their second album, Days Of Future Passed, that summer. It was a song cycle based around keyboard player Mike Pinder’s box of tricks, the Mellotron, and with contributions from The London Festival Orchestra. “We’d already written Nights In White Satin. So we were heading that way.”

The Moody Blues added Sgt Pepper to a pile of inspirational records that also included Holst’s The Planets Suite and The Zodiac: Cosmic Sounds, an album of Moog instrumentals narrated by the US folk singer Cyrus Faryar. “We used to get very stoned and listen to that. It all fed into the mix,” says Hayward. Not least the narration on Days Of Future Passed’s opening track, The Day Begins.

The revolution was not just confined to the UK. UFO club co-founder and London scenester John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins acquired a tape of the Velvet Underground’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable show in New York, which he played to everyone. “That made a dent in people’s consciousness back in London,” Hoppy told the author. “It fitted into the scene.”

On America’s West Coast, folk rock groups such as the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane developed a new sound partly inspired by their drug use. Jefferson Airplane’s Alice In Wonderland-themed 45 White Rabbit encapsulated the so-called ‘summer of love’ as perfectly as Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds.

“We listened to everything coming out of America: The Byrds, The Beach Boys, anything on Elektra Records, The Doors, Love,” says Justin Hayward, who singles out Neil Young and Stephen Stills’ group Buffalo Springfield “as a major influence on the London scene.”

However, there was one crucial difference between the UK and the US. America was at war. British teenagers might get busted or have a bad trip, but they didn’t have to fight in Vietnam. You could detect young America’s fear in some of their music. The Mothers Of Invention’s June ’66 debut, Freak Out!, was the first of Frank Zappa’s attacks on corporate America and the booming counter-culture. Zappa poked fun at ‘straights’ and hippies equally. His 1968 Sgt Pepper… parody, We’re Only In It For The Money, would become a cynical running commentary on the era.

American psychedelia didn’t lead to the gentle whimsy of 70s prog. Instead, it grew horns and turned into Captain Beefheart’s Trout Mask Replica or the heavy stoner rock of Blue Cheer and Iron Butterfly.

But where British groups had once looked only to America for inspiration, from ’67 onwards they were looking towards European and Eastern music as well. Like The Moody Blues, with their shades of Dvorák and Strauss, Procol Harum were another lapsed R&B group who ‘went classical’. Their No.1 single, A Whiter Shade Of Pale, was inspired by Johann Sebastian Bach. Although nobody really knew what vocalist Gary Brooker was singing about (‘One of sixteen vestal virgins, who were leaving for the coast’, anyone?).

“It’s like the construction of a jigsaw puzzle without knowing what the finished picture will be,” explained lyricist Keith Reid. “I start off with one or two pieces or fragments of a concept, then, by interlocking pieces, I build up a picture that makes sense and conveys my thoughts and meaning.” He could have been Jon Anderson talking about his lyrics for Yes.

But A Whiter Shade Of Pale sounded like it meant something. And that’s what mattered. Paul McCartney had his first listen in London’s Speakeasy club and thought, “This is the best song I ever heard, man.”

For Traffic, another new group with roots in the 60s beat boom, Procol Harum’s single was a bittersweet experience. Traffic’s frontman Steve Winwood and his bandmates had been holed up in the Berkshire countryside writing their debut album, Mr. Fantasy, for several months. They released their first single Paper Sun a week after A Whiter Shade… in late May ’67. Paper Sun was all Indian jangles and dreamy flutes. But Winwood and Gary Brooker were white men who sang the blues. Their voices sounded alike – and Brooker beat Winwood to No.1.

Traffic deliberately released Hole In My Shoe, sung by guitarist Dave Mason, as a follow-up. It reached No.2 in August. But with its spoken-word monologue (‘I climbed on the back of a giant albatross, which flew through a crack in the cloud…’), it sounded like it was trying too hard.

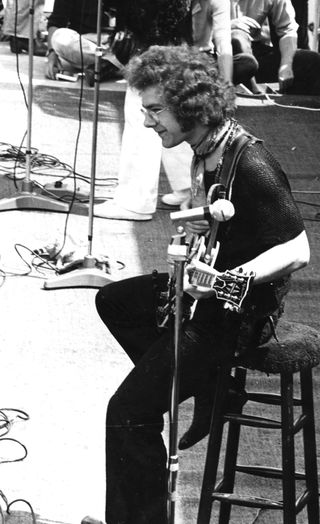

The second half of ’67 saw many artists hitch a ride on the next available giant albatross. Guitar heroes Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton put a trippy spin on the blues (with Are You Experienced and Cream’s Disraeli Gears, respectively), and The Incredible String Band did the same with Scottish folk on their pot-fuelled second album, The 5000 Spirits Or The Layers Of The Onion.

A new generation of art students also got in on the act. Kevin Godley and his future bandmate Lol Creme wangled a deal with CBS and released a single, Seeing Things Green, under the name The Yellow Bellow Boom Room. It was a song with stars on its cheeks and flowers in its hair – but recorded in Stockport.

“Imagine the summer of love painted by Lowry,” deadpans Godley. “We were just copying everyone else.” The duo’s next major job would be backing Sheffield’s resident cosmic rocker and amateur Egyptologist, Ramases, on his debut album, Space Hymns.

Suddenly, even older, bluesier groups were adding an Indian raga or a druggy lyric to the mix. The Rolling Stones’ Their Satanic Majesties Request LP arrived in December. But it was hard to take their token Eastern-sounding track Gomper seriously, or Mick Jagger dressed as a wizard on the cover. The Who’s The Who Sell Out turned up a few weeks later. It was partly a satire on pop culture, and contained one peerless single, I Can See For Miles, that chimed with the times. But the free psychedelic poster included with early pressings felt like a cynical cash-in.

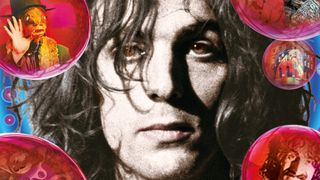

Far more convincing than the Stones or The Who were those new psychedelic groups who seemed to have come out of nowhere, such as UFO club regulars Pink Floyd and Soft Machine. Floyd’s August ’67 debut album, The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn, would become a cornerstone of progressive rock. Guitarist Syd Barrett couldn’t play like Clapton or Hendrix, so the band instead began making what bassist Roger Waters called “strange noises that didn’t sound like the blues”.

The songs on Piper… were not about cars, girls and teenage rebellion. They were about gnomes and Outer Space. Like The Beatles, Pink Floyd had made good use of Abbey Road studios. Furthermore, Syd Barrett sang in an English accent. Soft Machine’s Robert Wyatt and Kevin Ayers did the same. Soft Machine’s music, meanwhile, was nearer to John Coltrane than Muddy Waters. “They learnt to play instruments in order to play the strange sounds in their heads,” stated International Times in a review of the group’s 1968 debut.

Unlike Pink Floyd, Soft Machine would never have a hit. But both groups offered that English sensibility that later defined so much 70s prog rock. Their music was like a painting of a Victorian nursery or a sun-dappled croquet lawn, with the edges growing fuzzy as the listener’s trip began.

The problem with 1967 is that it didn’t end the way it began: full of hope. UFO had been raided and forced to close down, and Mick Jagger and Keith Richards had been busted for drugs and briefly jailed. The Beatles’ All You Need Is Love felt like a hollow statement.

LSD was now covered under the Dangerous Drug Act, and not every pop star who took it had escaped unscathed. Syd Barrett’s mental decline was exacerbated by his LSD use, and he left Pink Floyd in early ’68.

If the optimism of ’67 had receded, then the New Year saw the music becoming more ambitious and bigger business. Every label soon had its ‘serious’ groups. For Island Records it was Spooky Tooth, Traffic and, for a time, Jethro Tull; Decca’s Deram subsidiary had The Moody Blues, and EMI’s Harvest imprint had Pink Floyd. With David Gilmour replacing Syd Barrett, Floyd released A Saucerful Of Secrets, whose title track was a multi-part epic about warring alien civilisations. It went Top 10. Record company executives who’d once struggled to understand The Beatles now accepted that the stoned young man standing in reception without any shoes on could be the source of their next Christmas bonus.

These were strange times. The new music was even being discussed in the ‘proper’ papers. Journalist and filmmaker Tony Palmer became The Observer’s pop critic, and anointed The Beatles “the greatest songwriters since Schubert”. “And, God, was I ridiculed for that,” he said.

In February ’68 the BBC had commissioned Palmer to produce a serious pop culture documentary. All My Loving was a time-capsule snapshot of Pink Floyd, The Beatles, Zappa, Cream, The Who and Hendrix, intercut with footage from the Vietnam War. “These people were trying to say something important,” explained Palmer. “Rather than just write ‘Doobee doobee doo’.”

Psychedelia had peaked, but the legacy of Sgt Pepper was more groups making music that strove to go beyond ‘Doobee doobee doo’. In May 1968, the Small Faces released Ogdens’ Nut Gone Flake. Two years earlier the Small Faces had been Tamla Motown-loving mods. But they’d swapped pills for LSD, and bassist/songwriter Ronnie Lane now followed an Indian spiritual master.

Ogdens’… contained a song cycle about a boy, Happiness Stan, and his quest to find the missing half of the moon. It was narrated by comic actor Stanley Unwin in his trademark gobbledygook: ‘Are you sitting comfty-bold two square on your botty?…’

The Small Faces weren’t alone. A month later The Crazy World Of Arthur Brown released their self-titled debut. Side one included their No.1 hit Fire as part of a suite of songs about hell.

“I wanted to use the concept for both sides,” says Brown, who’d started as a soul singer but had adopted a flaming head-dress and a ‘God Of Hellfire’ persona in tune with the times. “But the record company told me, ‘Arthur, no one wants to hear a silly album that’s all about fire, for fuck’s sake.’”

Arthur Brown compromised. Others didn’t. The roll call of themed albums between 1968 and mid-’69 also included The Kinks Are The Village Green Preservation Society; The Moody Blues’ In Search Of The Lost Chord; The Pretty Things’ SF Sorrow, The Nice’s Ars Longa Vita Brevis and The Who’s Tommy. Widely, if wrongly, credited as the first concept album, Tommy was pitched to the world as a ‘rock opera’ and even began with a ‘proper’ overture.

What united this music was that it was terribly British. The Kinks serenaded a bygone England of cream teas and warm beer. On Tommy, Pete Townshend took his deaf, dumb and blind kid on a spiritual adventure, but set part of it in a Butlins-style holiday camp. No American could have made these records.

The Who performed their rock opera without an orchestra. In contrast, The Nice’s Ars Longa Vita Brevis contained an orchestral suite in six movements. “I suppose you could call what we’re doing ‘surrealistic pop’,” keys man Keith Emerson told Melody Maker.

Emerson, who started his career in a jobbing R&B band, Gary Farr And The T-Bones before backing US soul singer PP Arnold, was desperate to do something new. It might be construed as pretentious, it might not to be wholly successful, but it came from an honest place. “I’ve always hated copyists,” Emerson said. “I wanted to be different.”

That same sentiment drove the entire first generation of progressive groups. In October 1969, Pink Floyd released Ummagumma, a double album that contained a Stockhausen-inspired piano concerto and five minutes of manic birdsong and treated voices entitled Several Species Of Small Furry Animals Gathered Together In A Cave And Grooving With A Pict. But strangeness sold – and Ummagumma reached No.3. Above all, these groups had new ideas; occasionally grandiose and ridiculous new ideas, but new ideas nonetheless.

When Yes released their debut in summer ’69, it was the culmination of over a year finessing a glorious sound which borrowed from pop, folk, church music and even Hollywood soundtracks. Yes’ version of Something’s Coming from West Side Story was a highlight of their early shows. Their album saw them put a jazzy spin on The Byrds’ I See You and rearrange The Beatles’ Every Little Thing into a five-minute, 42-second mini-concerto.

“The way they took other people’s songs and changed them was amazing. I thought that was something I could do,” says Phil Collins, who watched Yes at the Marquee and credits them as a inspiration on his writing in Genesis.

But the real line in the sand was drawn in November that year. Three months after King Crimson’s appearance at Hyde Park, they released their debut album, In The Court Of The Crimson King. An unearthly sounding Mellotron, a dissonant saxophone and jagged time signatures had replaced the familiar tropes of conventional pop music. The LP even looked different. There was no band picture; just a floating open-mouthed face with a bright red uvula. “It was anti-format, anti three-minute singles. It was something new,” declared Greg Lake.

By the end of the month In The Court Of The Crimson King was battling it out with The Beatles’ Abbey Road and Motown Chartbusters Volume 3 near the top of the charts. Progressive rock had officially arrived. Not so much the sky, as the entire universe was now the limit.