In May 1986, Peter Gabriel released his fifth studio album. In the UK, it was the first to be given a title, rather than just his name, like his four preceding long‑players. Unlike those four, So became a global phenomenon because it contained a track called Sledgehammer and another called Don’t Give Up. The Stax-inspired elation of the former was matched by the Kate Bush-assisted introspection of the latter. Soon the album was topping the chart in the UK and nestling in the runner-up slot in the US.

So gave Gabriel the financial freedom to match the artistic independence he had enjoyed ever since he left Genesis in 1975. A performer with some of the loftiest ideas in popular music, Gabriel had faced bankruptcy in 1982 and had to be bailed out by his old group after the artistic triumph, yet commercial catastrophe, of his first World Of Music And Dance (WOMAD) Festival in 1982. As a perfectionist who spent increasingly long periods making albums, the monetary security of an enormous hit record was exactly what Gabriel needed.

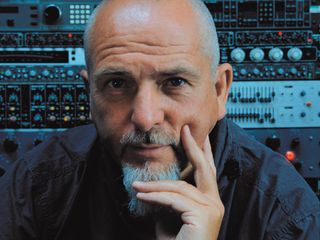

And when the revenue from the multiplatinum album and attendant tours came in, invest it he did. Taking the advice of his then-manager Gail Colson, Gabriel sank his cash into his Real World studio complex and label in Wiltshire, just outside Bath. From this 200-year-old converted mill, he would mastermind his operations; A&R some of the most innovative music from around the globe; keep an eye on WOMAD, now becoming one of the world’s most successful festivals; have his own studio ready and waiting for his often idiosyncratic recording methods; and finally, resume the business of being a pop star. This last part was to take the longest time.

Gabriel’s first releases on Real World were the groundbreaking Passion: Music For The Last Temptation Of Christ in June 1989, and then in November 1990, his first hits collection, Shaking The Tree: Sixteen Golden Greats. Passion… was an incredible piece of music that began life as the film soundtrack for Martin Scorsese’s controversial motion picture but then took on a life of its own. With typical Gabriel disregard for timelines, the soundtrack appeared just under a year after the film had been released. With its blending of folk, world music and ambient, it garnered a Grammy Award in the New Age (how very of its era) category in 1990.

But there was great demand for a new pop album. If Gabriel had released So II at the time, he may still be one of the world’s biggest-selling stars, but Gabriel being Gabriel, the album that began to take shape was one of the deepest, darkest records he would ever make. And now, of course, there was the shadow of following up ‘the hit’. Not that this was felt by everyone: “For those of us in the band, or playing back‑up on the album, there’s never any of the pressure that the artist might be feeling,” long-term bassist Tony Levin says. “With Peter, it’s always just a thrill to be part of some of his new music.”

When the new music was finally released in September 1992, So was six years old, a lifetime in pop music terms. The world had turned. It was the first Peter Gabriel album specifically made for CD – its 10 songs ran for just under an hour, and had to be offered as a double vinyl album. Its gestation period was lengthy, with recording beginning soon after So. Daniel Lanois returned as Gabriel’s co-producer.

“The first record I did for Peter was the soundtrack for Birdy,” Lanois says. “At that time he was living at Ashcombe House, in a tiny village. We were in a cattle barn at the end of a lane. When I first saw Peter at the end of the lane, I’d never met him, but when I shook his hand, I thought, ‘I’m with somebody I already know – let’s pick up from where we left off.’ He liked Birdy and he asked if I’d stay on to work on his song record.”

After the runaway success of said song record, Lanois returned to Bath, only this time to the new Real World studio. The Canadian had first worked with Brian Eno in the early 80s, and came to wider recognition as co-producer with Eno of U2’s The Unforgettable Fire. In the period between So and Us, his star, like Gabriel’s, had risen high in the firmament, working with U2 again on The Joshua Tree and Achtung Baby. Beyond this, he had become the go-to studio helmsman with acts such as The Neville Brothers, Robbie Robertson and Bob Dylan. “I was a kid then, I had a lot of power,” Lanois says with some understatement.

Unlike So, which had a variety of recording approaches, many adding rhythm tracks to Gabriel’s piano sketches, “We had the players from the beginning,” Lanois states. “It’s always a nice thing because you get a natural ebb and flow with the musicians in the room with you. When the singer sings, you catch the moment.”

“I remember that the musical relationship between Peter and Daniel seemed just right to make a creative album,” Us bassist Tony Levin said. “The tracks ended up being pretty diverse.”

However, there was a lot going on: “I trusted in Peter and what he was going through emotionally – there is no doubt about the truth that is in that record,” Lanois states. “But it was a tough record to make because of distractions – too many board meetings, architects going round with drawings, feeding the ducks. It was a frustrating time. I don’t like distractions very much, I’ve seen distractions destroy a lot of careers.”

One thing was clear: the new album was going to be very bald emotionally. “I see Us as a continuation of something we agreed on So: to strip away any kind of a veil,” Lanois says. “I didn’t want Peter to be hiding behind a mask. He had done so literally in the past. No veils any more. He agreed with me. We went on to make touching music on So. That philosophy came on into Us, and became more revealing.”

Us dwells on the breakdown of Gabriel’s long-term marriage to his wife Jill (from whom he’d split in 1987), his star-crossed affair with film actor Rosanna Arquette and his communication breakdown with his daughter. Gabriel always kept things light in his public persona but was searingly honest when asked in 1989 on TV show Star Test, “What’s the one thing in your life that you most would like but don’t have?” He replied, “Right now?” and stared into the camera. “A happy family.”

Us was made with over 50 musicians and recorded between October 1989 and June 1992 at Real World, in New Orleans and Dakar. “I let my emotions go in this album,” Gabriel told The Independent. “They’re very evident.”

To leave the listener with no doubt about the album’s content, Gabriel wrote this searingly honest sleevenote: “Much of this record is about relationships. I am dedicating it to all those who have taught me about loving and being loved. Especially to my parents, Ralph and Irene. To Jill, for giving me so much in all the time we were growing up together. To Rosanna for all her love and support that I didn’t properly acknowledge. And to my daughters Anna and Melanie, my pride and joy.”

It also acknowledged that Gabriel had spent time in therapy, by thanking ‘the group’ and providing their first names. As a result, Us was a complex, strange and interesting album.

Us contains some remarkable tracks. His duet with Sinéad O’Connor, Come Talk To Me, regards the breakdown in communication between Gabriel and his daughter Melanie, and it sets the often sombre tone for the record. “Sinéad is one of the greats,” Lanois says. “She picks up a microphone in the studio and you better be recording, because that is going to be a take. She is one of the pure hearts.”

Washing Of The Water is quietly soul-baring. “That’s beauty, isn’t it?” Lanois says. “Peter and I always took a philosophical stance: if the magic wasn’t there, we wouldn’t do it. Washing On The Water was like a hymn or a lullaby. Peter has a beautiful falsetto. When a man goes into a falsetto in such an empty landscape, emotion comes through. It was a song that meant a lot to Peter and we managed to capture it. May it live on.”

Lead single Digging In The Dirt is a darkly funky rumination on psychotherapy, featuring Richard Macphail and Peter Hammill on backing vocals. Sledgehammer it’s not. However, Gabriel did get a Top 10 single with the ultra-funky Steam, a rumination on sex, another of his favourite topics.

The album closed with the astounding Secret World, arguably Gabriel’s greatest solo moment: a tale of a doomed relationship, built on stolen hours. Gabriel comes close to emulating one of his heroes, Bruce Springsteen, and again, it’s rendered remarkable by the playing of one of his longest-serving cohorts, Tony Levin.

“I played the bass with my ‘funk fingers’ [drumsticks attached to digits, played hard on the strings], a fairly new device that had arisen from touring So. That was pretty special, working out the best way to record with that technique. I don’t recall whether it was Dan’s idea, or Peter’s, or mine, but the feel of it suited the song very well.”

The track is full of unexpected leaps in volume and distinctive, ringing keyboard sounds.

The reactions to Us were largely positive, but certain sections of the press were against Gabriel’s championing of world music and his use of the Real World stable.

“The British press were very cruel to him,” Lanois states. “Nightclub-driven values were in the press at the time. I think they need to provide an apology to Peter. Now that everyone is interested in Tinariwen and some of the fine music coming out of Africa, it needs to be said that the Brits got it wrong; Gabriel got it right. He was doing something humanitarian and beautiful and he was on display like an old, washed-up fart for embracing this music while everyone else was doing ecstasy in the clubs. I celebrate Mr Gabriel for doing that at a time when it was very out of fashion.”

Us marked the last time Gabriel and Lanois worked together on a whole album. “We were trying to make an intimate record in a very public place. We didn’t even have a telephone when we were recording So – I ripped the telephone off the wall and threw it in the ravine. With Us, all the communication systems started coming. Every studio had phones – we might have done better to go to a quiet place.

“The complexities surrounding Peter at that point made it hard and probably made it so we wouldn’t be working together again. We never said that, but I think we both felt it. I hope his life has simplified since then – that’s a deep, kind soul, and a man who has done a lot for a lot of people.”

From then on, Gabriel stated that music, once his all-consuming passion, was now one third of what he did, between humanitarian work and managing his label. He wasn’t stopping making music, just scattering his work across soundtracks and projects.

To that end, it’s a wonder that Up saw the light of day at all. Stretches of it make Us look like a walk in the park, and it offers some of the most daring music that Gabriel has committed to disc. In the interim, he had completed the lengthy Secret World tour, which resulted in the double live album of the same name; OVO, the musical piece to accompany the show at the Millennium Dome; and Long Walk Home, the music from Phillip Noyce’s film Rabbit-Proof Fence.

Up was recorded mainly with Gabriel’s trusted engineer, Richard ‘Dickie’ Chappell, and was released on Real World in September 2002. Basic tracks had been recorded as early as 1995 at Real World, with sessions continuing at Youssou N’Dour’s studio in Senegal and at Meribel in France over the following years. The majority of Up was recorded in the Writing Room at Real World: Chappell kept Gabriel’s keyboards and microphone live, so whenever Gabriel was ready, he could get to work.

Originally entitled House In Woods, Darkness is the album’s blackest track, and the decision to put it first was a warning to all those casual listeners who were expecting So II. Gabriel was adamant that this uncomfortable track should open the album. It’s a musical version of a fairy tale – getting lost in a dense forest of tangled thoughts before coming to clearings where fear is confronted, and the music reflects this. After 30 seconds of deliberately quiet synthesised bleeps, a sonic assault of David Rhodes’ squawking guitar makes it resemble a death metal record.

The tone is set for the album: nine other suitably long tracks, often ruminating on death. This was grown‑up, progressive work, with moments of sheer beauty, such as Sky Blue, featuring the remarkable harmonies of The Blind Boys Of Alabama. Then there was the stirring Signal To Noise, with Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, whom Gabriel effectively introduced to Western audiences, in one of his final performances, taped before his death in 1997.

Some 14 years have now lapsed since Up. Gabriel has worked on a variety of projects, yet none have been that elusive pop follow-up album. One thing is sure, though, and that’s how prescient Charisma were when they used this marketing slogan in 1977 for his debut: ‘Expect The Unexpected’. It would apply for his entire career.

“I know better than to predict what Peter will come out with,” Tony Levin says. “When I think of the very wide range of music he’s done, I think it’s unlike any other artist. So if he does another album like some in the past, I’d be happy to be part of it. But if he breaks out in a new direction, as he’s done often before, again, I can hope I’ll be there playing bass on it. But if not, I’m still going to be excited to hear it, as a fan.”

The remastered vinyl editions of So, Us and Up are out now on Real World. See Peter Gabriel’s website for details.