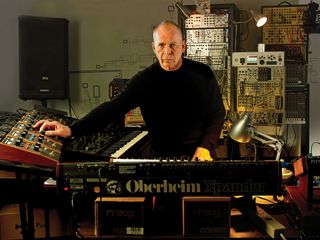

‘Polymath’ is a much-abused term these days, but Peter Baumann is without doubt the real deal. From 1971 to 1977, he was a member of Tangerine Dream at a time when the band were expanding the frontiers of progressive electronic music with a series of landmark albums, including Phaedra and Stratosfear.

After leaving the band, he pursued a solo career before founding the Private Music label. Here, as producer and company head, he championed instrumental electronic/acoustic artists such as Yanni and Suzanne Ciani, and helped reboot the careers of jazz and blues icons such as Etta James and Taj Mahal. And then, wanting to reach out beyond his musical hinterland, he founded The Baumann Foundation, a think tank created to explore the experience of being human in the 21st century. He also co-authored a controversial book on the “evolutionary implications of the September 11 attacks”.

But the reason Prog is talking to Baumann today is because 33 years since his last record, he’s released Machines Of Desire, a new album that both embraces the darker end of modern electronica and harks back to his classic work from the 1970s. However, the initial sessions that gave rise to the album started on a tragic note. Baumann had maintained his friendship with Tangerine Dream founder Edgar Froese over the years, and when he found himself bitten once again by the music bug, he met with Froese in early January 2015 with a view to a possible collaboration.

“We left it that I would do a couple of sketches and come back in February to see if he wanted to work on it or not. When his wife Bianca called me, I said, ‘Okay, let’s talk about the dates we’re going to meet,’ but she said, ‘Peter, I have really bad news for you…’”

Froese had died suddenly just a few days after their meeting from a pulmonary embolism.

Born in West Berlin in 1953, Baumann grew up in a relatively arty household – “By German standards, it was controlled nuttiness” – and began playing in a covers band from the age of 13, with regular gigs at the city’s American GI clubs. In 1971, he was at an ELP concert and got talking to Tangerine Dream’s Christopher Franke. “I said, ‘I’m in a band that plays standards, but I do this experimental stuff on the side.’”

Two weeks later, he got a message from Franke that they needed a keyboard player. “So I put my organ under my arm and went to their rehearsal room. Edgar was a very cool character – I set my equipment up and said, ‘What are we going to play?’ and he said, ‘We’re going to start in C – just play.’”

And that’s essentially what they continued to do for the next few years. “There was a unique atmosphere between Edgar, Chris and myself: the chemistry was just extraordinary. It was electrifying when we played together.”

We felt that Britain accepted us with open arms and really appreciated where we were coming from, certainly more than in Germany.

The first two albums produced by this line-up – Zeit and Atem – were full of drifting, cosmic dronescapes, and were decidedly avant-garde. “We never thought of being a successful band; we just loved doing crazy stuff, really indulging in sound and space. We never thought we’d be popular and sell lots of records.”

All of that was soon to change though. John Peel named Atem as his favourite album of 1973, while Virgin Records, at the time a mail-order company specialising in imports, sold over 15,000 Tangerine Dream records to British fans. Unsurprisingly, Richard Branson quickly snapped the band up for his nascent record label, with Phaedra being one of its first releases.

“I remember being on holiday in Italy and Richard sending me a telegram saying, ‘You’ve got to come to London, Phaedra is on the charts,’ and I said, ‘What charts?’ I wasn’t even aware of something like that existing. It was extremely exciting. I was only 20 years old.

“We felt that Britain accepted us with open arms and really appreciated where we were coming from, certainly more than in Germany. A prophet in his own land doesn’t count for much.”

The spacey, electronic-driven music that Tangerine Dream were making was almost without precedent at the time, which led to much head-scratching from the media. “They asked us, ‘Why are you doing it?’” says Baumann, “but there was no simple answer. There was no calculation behind it – I still don’t understand why we did it!”

Phaedra introduced sequencers into Tangerine Dream’s sound for the first time, and also saw a move into more melodic territory. Their subsequent series of albums for Virgin would see the band becoming increasingly prog-friendly, with Ricochet and Stratosfear introducing guitar, piano and electronic percussion. Baumann feels the group were definitely aligned with the contemporary progressive scene, but weren’t influenced by the German kosmische bands: “We were aware of them, but we were more influenced by Ligeti, Morton Subotnick, even Pink Floyd, especially Ummagumma. The far edges of the more peculiar and bizarre stuff.”

Tangerine Dream were also notable for taking electronic music on tour, though this wasn’t without its challenges. “Our instruments were like unruly children,” Baumann explains. “They’d go out of tune and we’d have to adjust them during the concert. But I appreciated that it was unpredictable – magical things happened that you could never conceive of in the studio. We were pushing what was possible in music.”

Not everybody was convinced by their live set-up of three guys sitting behind banks of keyboards – Lester Bangs famously opined that he had seen God, yet was still bored. But speaking at the time, Baumann suggested that “the distinction between us and a rock band is that they put on a show – we put on a mind show”.

Despite a run of successful albums, Baumann left the group in 1977, feeling they were beginning to repeat themselves. He had already recorded his first solo album prior to his departure, 1976’s Romance 76, which he followed up in 1979 with the similar but more compact Trans Harmonic Nights, both of which have just been remastered and reissued. Romance 76 in particular is an overlooked classic, the minimal proto-electronica of its first half followed by an ambitious orchestral/choral/avant-progressive suite conducted by his father. “He had access to the Munich Philharmonic players, so I said, ‘Here’s what I’d like to do,’ and we took an afternoon and just recorded it.”

Following a move to America and a brief flirtation with synth-pop on the albums Repeat Repeat and Strangers In The Night in the early 80s – “It was just an adventure, not my musical home” – Baumann moved into production and founded Private Music. Initially tagged a New Age label due to similarities with Windham Hill, it soon outgrew this bracket and was bought by BMG in 1996. Then came The Baumann Foundation.

“I woke up one day in my mid-40s and realised I had 10,000 days left to live in terms of average life expectancy. And I asked, ‘How am I going to live those 10,000 days?’ It was an extraordinary time in my life where I talked to researchers, scientists and spiritual teachers. I wanted to focus attention on what we’re doing here to begin with.”

And his conclusions? “The most basic insight I took away is that we are far less in control than we think we are. Most things emerge out of our history, our genetics and our environment.”

And then music took hold again. “I’d been involved for 15 years in very philosophical and psychological pursuits, and I came to an end point where I had the desire to do something creative that was non-verbal and non-analytical.”

There was a unique atmosphere between Edgar, Chris and myself: the chemistry was just extraordinary.

Baumann completed the musical sketches he had prepared for Froese in his home studio and continued writing until Machines Of Desire appeared in its entirety. He agrees that the album references his earlier work, both solo and with Tangerine Dream – “This music is just part of my internal fabric, and some of the themes are perennial themes” – but there’s also a harder, almost industrial edge to much of the material. And while there are moments of melodic uplift, there’s also a palpable sense of foreboding on its tracks.

“Music by its very nature reflects society and culture. We do go into these dark areas in our lives and psyche, but it’s an important part of human experience that we shouldn’t shy away from.”

Asked about his view of the future, he says, “I call myself a 51 per cent optimist. I feel we have a better than 50⁄50 chance that we’ll progress and mature as a species, but there’s also a good chance that the whole thing’s going to go to pot!”

But his joy at returning to his first love of music is unquestionable. “I can’t tell you how much I’m thrilled to have the chance to do this – I never thought I would do another album. I feel like a kid in a candy store, and I haven’t even scratched the surface yet.”

Machines Of Desire is out now on Bureau B. Visit the microsite for more information.

Peter Baumann - Machines Of Desire Album Review