“I’d heard all these stories of bands who opened for The Clash and I wondered if it would happen to us,” says drummer Chris Layton, laughing. “And it did!”

“Their audience tore us apart,” he recalls. “They threw stuff at us, yelled and gave us ‘the bird’. After the show was over, Stevie went back to Joe Strummer and said, ‘Hey man we’ve never played an audience like this! If it’s cool, we would rather not play tomorrow night’. Joe said that was fine. He totally understood.”

That evening ended in disaster but they would live to fight another day. Over the course of the next 12 months, their fortunes would be completely transformed. They’d see international rock icons fall at their feet, sign a record deal with one of the biggest labels in the US and release the landmark album Texas Flood, which dragged the blues kicking and screaming into the 1980s. The legend of Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble was born…

Like most ‘overnight sensations’, Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble’s massive success when Texas Flood was released, on June 13, 1983, was a long time coming and not without a few technical hiccups along the way.

All three band members – Layton, Vaughan and bassist Tommy Shannon – had played in countless bands on the Texan circuit for many years, before eventually joining forces to create the ultimate power trio, which is still seen by many as the benchmark of modern blues.

Vaughan himself was born at the Methodist Hospital in Dallas on October 3, 1954 and had been playing in bands since the early 70s. In 1972, he briefly joined the rock band Krackerjack and it was there he first met future Double Trouble band member Tommy Shannon, who had already seen the teenage Vaughan play guitar a few months earlier at The Fog nightclub in Dallas.

“I first met Stevie in 1976 in Austin,” says Layton. “I was from Corpus Christi and came here in 1975 and he came here in 1972. It was a chance meeting. I went out to see a friend of mine [sax player Joe Sublett] and they were playing in a band together, Paul Ray and the Cobras. Their drummer was late and nobody knew me, except Joe, and they got me up to fill in. I played four songs with them and that’s how we met.

“I was absolutely enchanted by Stevie. I walked in and I thought I had never seen anything like him. I couldn’t put my finger on it. There was something about his energy and his passion. It was like walking outside and seeing the sun in the sky. Everybody was really good in that band, but Stevie had this thing I couldn’t put my finger on.”

Paul Ray and the Cobras soon began to cause a stir on the burgeoning Austin live music scene, as did the Fabulous Thunderbirds, which featured Stevie’s older brother, Jimmie, on guitar and Kim Wilson on vocals and harmonica.

“It was more of an R&B band,” recalls Layton. “Stevie would sing two or three songs a night and she would sing the rest. We would do a couple of instrumentals. She was the onstage leader and talked to the audience. We would do Little Richard, Jimmy Reed and Slim Harpo songs.”

In 1980 their bass player, Jackie Newhouse, left the band which meant they were on the lookout for a new member. It was at this point Tommy Shannon entered the scene and a legendary rhythm section was born.

Shannon had spent several years away from the music scene, struggling with drug abuse, serving time in jail and on probation. At one point, he was laying bricks for a living as the terms of his probation banned him from the drug-driven local music circuit. By the end of the 1970s, he was out of probation and now living in Houston. Shannon decided to resume his music career and remembered the scrawny young kid he had played with in Krackerjack all those years ago.

“I moved him from Houston to Austin in January 1981,” says Layton. “He sat in with us. He was hard to describe, but I liked him. He came into the room and said he wanted to jam with us guys. I think he wanted to be in the band and he made that known. He was pretty large about it.

“We were playing around Texas in clubs which held 500 or 600 people,” says Layton. “Every once in while, we went to northern California for a trip. Occasionally, we went to Rhode Island, because we were friends with Roomful Of Blues.”

A few months later, they played their ill-fated gig with The Clash and then, on 17 July, 1982, Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble became the first unsigned band to play the prestigious Montreux Jazz Festival. Their performance that night has since gone down in the music history books, although not everything went according to plan.

- The Rolling Stones: The Story Behind Honky Tonk Women

- Stevie Ray Vaughan: Buyer's Guide

- Ray Of Light: Stevie Ray Vaughan

- The 10 best David Bowie riffs according to Hotei

Their first day, Friday November 22, was spent just setting up equipment, leaving them just the Saturday and Sunday to put the tracks down. The set was made up of songs they had played night after night on the circuit, including Buddy Guy’s Mary Had A Little Lamb and Howlin’ Wolf’s Tell Me, as well as Vaughan’s originals, such as Love Struck Baby and the instrumental Lemmy.

“We set up in the middle of the floor, like we were playing a gig inside a warehouse. We ran through all the songs on Texas Flood about three times and took the best songs from the three run throughs. It was just a warehouse. You would look around and see flight cases. There was a big open space in the middle of the floor, where we set up the band.

“The thing about Texas Flood is we were not going in to make a studio record,” he adds. “We played the music the way the band played every night and we recorded it.

According to Layton, the band were so unprepared for the recordings that Stevie borrowed a Dumble amplifier off Jackson for some of the session.

“They’re very expensive now, but Jackson just had this little one which Stevie borrowed. We didn’t even have tape with us. We actually recorded Texas Flood over an old tape, which Jackson Browne had used to do pre-production on his record Lawyers in Love. We were really not prepared. We just packed our stuff, begged, borrowed and stole, and played and music.

“Stevie sang all the songs as we played them,” he adds. “We went back in and he recorded a handful of vocals, but some of them are the original vocals. We were feeling good. We had just come from Europe and were hanging out in an apartment in Los Angeles. Eight months earlier we were playing bars in Texas, so the mood was great.”

It was while they were in Los Angeles that Stevie had the call from David Bowie, inviting him to be part of the band for his next album, Let’s Dance.

With the Texas Flood recordings in the can, the band returned home to Texas and Stevie headed the New York to join the other musicians assembled by co-producer Nile Rodgers. The crack squad included Chic drummer Tony Thompson and a young bass player by the name of Carmine Rojas (who these days tours with Joe Bonamassa).

“There were a few bass players involved,” recalls Rojas. “Some fell by the wayside so I ended up doing most of the album, but Stevie was there. I heard a conversation with Bowie about meeting him the year before in Montreux. I think it was Keith Richards who told Bowie about Stevie Ray and told him to check him out.”

“He wasn’t just a blues guitar player. He had the spirit of Albert King and Jimi Hendrix. A lot of guys could emulate those two, but this guy had the heart and soul. We were all going ‘what the fuck?‘. The studio windows were rattling, because he had stacks of Marshalls in the room while doing the overdubs.”

“I think Stevie came back again a week later, but it was all cut pretty quick. The whole thing took about three weeks.”

But while Stevie was busy working with Bowie, the remaining members of Double Trouble and their management had turned their attention back to the recordings they made at Jackson Browne’s studio.

“We contacted John Hammond, who we had previously almost worked with on a deal and he went to Epic Records,” says Layton. “He had gotten involved with us about a year and half earlier, when we did a recording for a radio station. John’s son got hold of a copy of the tape and John heard it and loved it. He was our biggest fan.”

“We mixed the whole album in two days,” recalls Clapp. “John Hammond was a purist and wasn’t into special effects. He didn’t want to labour the point. We just did straight-ahead mixes of what was recorded.

“We did one vocal with Stevie Ray Vaughan on one of the songs, but everything else was live as they recorded it.”

According to Clapp, Hammond was excited about his new project, although being a consummate professional, he didn’t let it show.

“His style was to come in when we started the mix session, sit in the chair and read his newspaper,” he adds. “He wasn’t jumping up and down behind the console with us. He was pretty cool. We would mix a song and he would say ‘Good! Okay! Next song!’”

“I think it sounds as fresh now as it was then. I might mix it slightly differently now, because experience changes you as a mixer. At that time, I was trying to get a live sound and I did pipe the drums out into the studio, which had been a church at one point and had a high ceiling. I recorded the sound in the room and added that to the sound of the drums.

“The guitars were just huge. I did use a few pieces of outboard gear, such as the Roland Dimension D on the guitars, which spread the stereo feel of it a bit.

“The bass sounded very good as it was recorded. I was happy with it, but Tommy said he wanted to roll off the high end a bit, to make it sound rounder and less pointed. It was his call and tried to do a little bit of what he wanted, without going too far.

“It got me interested again in blues and how you could play 12-bar blues and still come up with something fresh,” says Clapp. “Some of it was tired, but this was a different approach, it was exciting. “John Hammond carried some weight, but it was near the end of his professional career. I didn’t know whether he still carried the kind of weight he had before to bring an album to the forefront, but it certainly came to front very quickly.”

Layton says that Hammond no longer had the ability to sign an artist himself at Epic and instead went to the head of the label’s A&R department, Gregg Geller, who gave them a record contract.

In March 1983, Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble were signed to Epic Records and their debut album, Texas Flood, was slated for release in June.

“We rehearsed in Dallas for a little bit over a month, which made it easy for him because he was home with his girlfriend at the time,” remembers Rojas. “I got to meet a lot of his friends. It was a good hang!”

According to Rojas and Bowie historian Nicholas Pegg, several bootlegs of the Dallas rehearsals exist with Stevie playing with the band. Everyone was very pleased with what he was playing. But, as Pegg notes in his encyclopaedic tome, The Complete David Bowie, there were issues with Stevie’s fondness for narcotics, which did not sit well with the British singer, who was banning drugs for the tour. Pegg says another “can of worms” was created when Vaughan saw the video for the title track of Let’s Dance and realised that Bowie was miming his guitar solo. There were growing problems with Vaughan’s management over the fee he was receiving for his work. Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble also famously did not do set lists, so quite what Vaughan made of the choreography and the structure of a tour like Bowie’s is anyone’s guess.

Whatever the problems in Dallas, Stevie and the rest of Bowie’s touring band returned to New York, and got ready fly out to Europe for full-scale production rehearsals. But on the morning the band departed for the airport, Stevie was left behind on the pavement, tragically waving at the bus as it drove off.

“It was so sad that he didn’t make the tour with us,” says Rojas. “His manager was trying to get more money from Bowie’s company. I guess they felt they were being stonewalled. I remember being on the bus and I saw Stevie’s bags [on the pavement]. I asked [band leader] Carlos [Alomar] what was going on and Carlos said ‘I’ll tell you in nine hours’. As we were leaving, Stevie was looking down. I felt gutted, because he was really a sweet-hearted guy. Nine hours later, we got to Europe and I heard down the hallway of the hotel that Earl Slick was flying over and learning his parts on the plane. That was the end of that!”

Whether Stevie was fired or, as some contend, quit the Bowie tour, is a moot point. What most people can agree on is that Stevie exited stage right days before the curtain went up on the opening night, which was on May 18, 1983 in Brussels. It was also great PR for anyone who happened to have a record coming out.

“We had a publicist, Charles Comer, who had come over to the US with The Beatles, stayed in New York and never went back to England,” says Layton. “He knew people everywhere and was tied in with press all over the world. When Stevie left, he put out a story that Stevie Ray Vaughan had resigned from the tour. Everybody wanted to know about Stevie!

“The news was, who was this guy, this nobody from Texas and how could he quit David Bowie? Nobody would quit David Bowie on the eve of the biggest tour in history at this point of time. They wanted to know everything about him – where he eats, where he lives, what kind of car he drives – they were fascinated he could do something like that. It was the best press money could buy.”

And on June 13, 1983, Epic released Texas Flood onto an unsuspecting and blues-starved world.

And, unlikely as it now seems, this battle-hardened combo even became pop stars. The video for Love Struck Baby was regularly played on the fledgling MTV channel, along with George Thorogood and the Destroyer’s Bad To The Bone. The blues was officially back in business. “They didn’t have enough videos to play 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” adds Layton. “They would just keep showing the same videos over and over again. We made a video and they played it all the time. They would show Love Struck Baby fives times a day, which added more exposure to the band.”

The album peaked at No.38 immediately after its release on the USA Billboard 200 charts, while Pride And Joy made it to No.20 on the mainstream rock tracks chart. Almost a month after the release of the album (July 11), the band appeared at a small nightclub in Toronto called the El Mocambo. As luck would have it, a film crew captured their performance on tape, although Live At The El Mocambo was only released (officially, at least) on video in November 1991, a year after Vaughan’s death.

Initial reviews for Texas Flood were certainly impressive. Texas Monthly hailed Vaughan as the “most exciting guitarist” to come out of the state since Johnny Winter and American music critic Robert Christgau compared his guitar playing with Alvin Lee’s and Robin Trower’s.

But not everyone was impressed. Kurt Loder in Rolling Stone said Vaughan’s singing was “genuinely generic” and that he couldn’t write lyrics, either. “Stevie Ray does his thing well but, essentially, it’s somebody else’s thing,” said Loder, who concluded his review by adding: “Texas Flood is well worth hearing, even if you have heard it all before. After all, it’s been a long time, right?”

But, Layton points out, Texas Flood came when new wave bands, such as Culture Club, Talking Heads and Psychedelic Furs were dominating the charts.

“We got lucky,” says Layton. “We had labels [in the past] say ‘You’re a great band, but nobody wants to buy this music anymore. If you made your band sound more like this band…’

“When Texas Flood came out, people our age had never heard anything like it. They said it was cool. They didn’t say we sounded like Freddie King in 1961. It just sounded like new music to them.”

The band embarked on a long tour of the US and Europe, including dates supporting the Moody Blues, of all people.

When I interviewed Shannon in January 2007 about the album’s sudden success, he said: “There was a club in California and there used to be 50 people there whenever we played it. Then just after Texas Flood came out, there was a line of people around the building.

“We said ‘Is there another band playing tonight?’ They replied ‘No, they’ve come to see you’.

The following year, the title track of Texas Flood was nominated for a best traditional blues performance Grammy, while another song, Rude Mood, also received a nomination in the best rock instrumental category. Along with the Robert Cray Band, George Thorogood and the Fabulous Thunderbirds, Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble became torchbearers for a new generation of blues fans.

It was the start of a roller coaster journey, with a series of trailblazing albums and a never-ending tour schedule, which came crashing to a halt when a combination of drink, drugs and exhaustion caused Vaughan to collapse in Germany in September 1986.

“After Soul To Soul and Live Alive we started feeling that we were heading for a brick wall,” said Shannon in 2007. “But at the same time, we couldn’t quit. I got clean and sober at the same time Stevie did. We both leaned on each other to make it. The first year was really bad. After that it became easier.”

Both Vaughan and Shannon entered rehab on the same day and after wrestling with their addictions, a leaner, meaner and cleaner Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble returned to live performing and even more critical and commercial success.

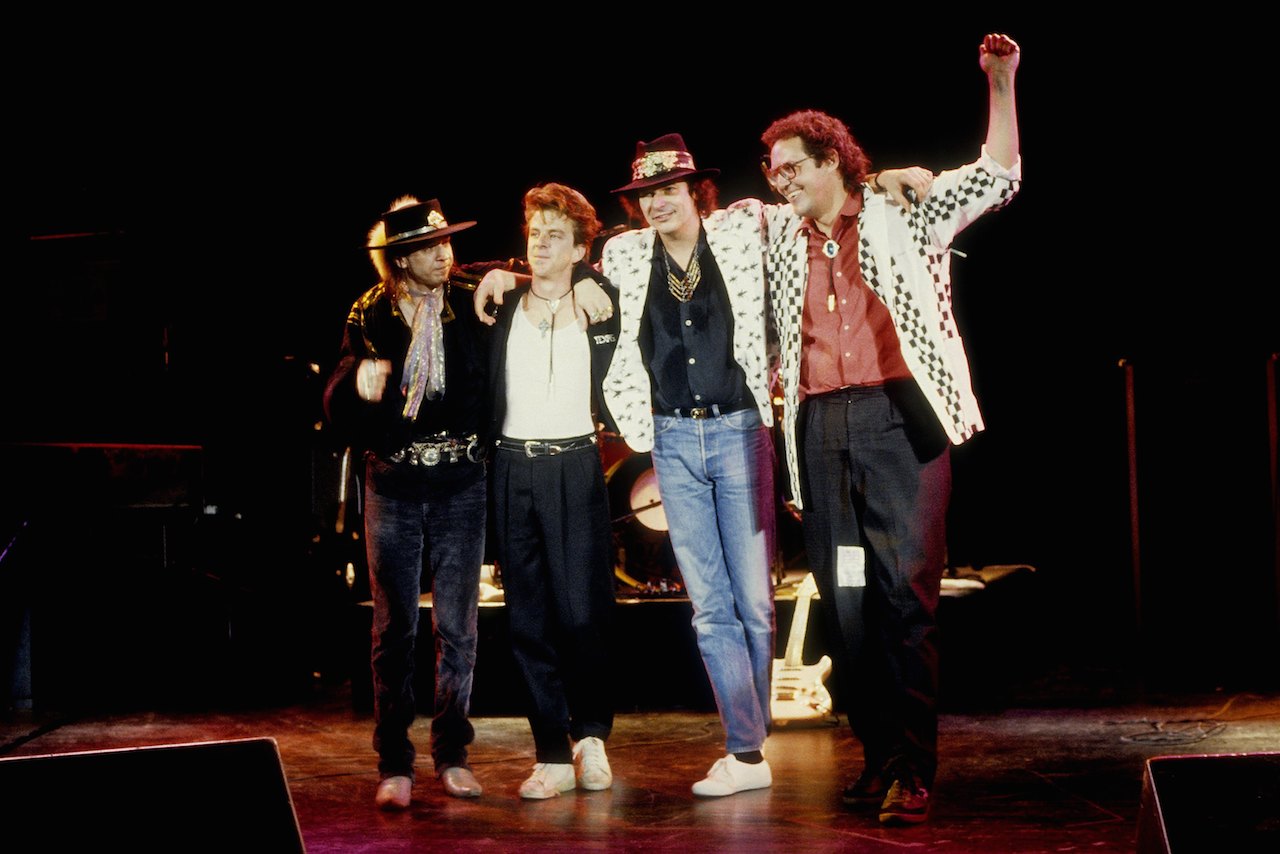

Sadly, as everyone knows, their story came to a tragic and far-too-early end on August 27, 1990, when Vaughan was killed in a helicopter crash in East Troy, Wisconsin, after performing in an all-star concert with Eric Clapton, Robert Cray, Buddy Guy and his older brother, Jimmie. He was just 35.

“From the moment Texas Flood came out to when Stevie died, we almost never stopped working,” says Layton. “We worked almost as hard as James Brown!

“We never contrived anything,” he adds. “We did the music the way we wanted to do it and that’s what I hear through all our records.”

“I went to a few of their gigs, because I wanted to see them live,” says Clapp. “I saw them down on Washington Square in New York. They were so tight, so practised and Stevie carried the show unbelievably. It’s hard with a trio. You have to be really good and he was. Like many of the greats, he made it look easy.”

And Rojas, who, having played with both Vaughan and Joe Bonamassa is probably more qualified to talk about blues legends than most, adds: “Like Joe, Stevie was very strong on his live show. You have to make people come back. You have to leave them gasping!

“But it’s not just what he plays,” adds Rojas. “It’s how he plays. Most guys are very good, technically, but they’ve got no spirit. You need to have the two. Texas Flood is an emotional song. You put it on and it sound like he’s coming through the speakers. He wasn’t bullshitting around.”

Thirty years on and Texas Flood is still rightly held up as a landmark album. It has that rare combination of incredible musicianship, great songs and even greater performances. For many, it was their first introduction to the blues and still sounds as fresh today as it did back in June 1983, when it was first released.

“Stevie was just a fucking great player,” says Layton. “He just floored people. He transcended the genre. It’s like Jimi Hendrix – no guitar player ever says he was ‘just okay’. He was a great guitar player. All he knew was that he wanted to play guitar and music the way he wanted to.

“We never thought of success or record sales,” he adds. “All we did was play our music. New generations have come along and they buy our records. As time goes on, I get more amazed – as opposed to less!”