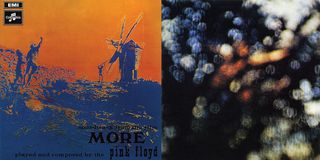

The delight of The Early Years 1965-1972 is that it offers the opportunity to reassess fully the variety of movie work that Pink Floyd were involved with in the first part of their career, and among all the multi-disc splendour, to finally bring into their official canon the films themselves: More and Obscured By Clouds.

These seven years highlight the band’s fertile relationship with left‑field filmmakers. From their very first appearance, it was obvious that Pink Floyd’s music was the perfect accompaniment for visuals, as their pioneering Mike Leonard-designed liquid light show expertly demonstrated to early enthusiasts.

After their troubled, charismatic frontman, Syd Barrett, left the group in early 1968, the group’s increasing facelessness underlined their desirability to filmmakers, with their blankly emotional soundscapes adding gravitas to any cinematic climax.

There are four major film works that Pink Floyd are linked to from this era: Barbet Schroeder’s More and La Vallée (Obscured By Clouds); Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point; and Adrian Maben’s not-actually-live-in-concert Pink Floyd: Live At Pompeii. But beyond these, the Floyd’s music is scattered throughout various films.

We started at nine each morning and did 12 hours or so. Roger was always there at 8.30, David Gilmour shortly after, then Nick Mason, and Rick Wright just before nine. It was amazingly professional.

However, before these, there were significant moments in their film CV dating from right at the outset of their career. Peter Whitehead’s documentary Tonite Let’s All Make Love In London and Peter Sykes’ The Committee were just two examples of how the Floyd could be called on to provide an instant trip to your movie.

Tonite Let’s Make Love In London was a fantastic capture of London at the summit of the 60s. Essentially a document measuring just how far England’s capital swung, it interspersed interviews with scenesters such as Mick Jagger, Eric Burdon and Julie Christie with footage from the fabled April 1967 14 Hour Technicolor Dream at Alexandra Palace. It captured the band three months earlier at Sound Techniques in Chelsea recording a fiery version of Interstellar Overdrive, and the rather less flammable tom-tom driven 12 minutes of Nick’s Boogie.

The Committee from 1968 was a different matter entirely. The 55-minute film saw Pink Floyd contribute arguably little more than a glorified collection of sound effects. Director Sykes’ initial idea had been to work with Syd Barrett, but as he had left the group, that was not to be. Writer Max Steuer recounted that Pink Floyd were tremendously together when it came to their contribution.

“We started at nine each morning and did 12 hours or so. Roger was always there at 8.30, David Gilmour shortly after, then Nick Mason, and Rick Wright just before nine. It was amazingly professional. The road crew set up the first day by 8 o’clock or so.”

The two main recordings were drone-led, helping usher in the band’s next phase. The plot, very stylized and surreal, centred on Paul Jones as a hitchhiker hauled up before a mysterious committee, called to explain a man’s murder. It was tremendously in-era.

These films were relatively low-key. Their next venture, More, was not. Pink Floyd’s relationship with Iranian director Barbet Schroeder – a protégé of Jean-Luc Godard – was to be easy and productive. Nick Mason recalls in Inside Out that the group’s members were paid £600 each for the work, which was a not insignificant amount for eight days’ work around the festive season in 1968. As Mason notes, “Roger came up with a number of songs for the film that became part of our live shows for some time after.”

One of those, Cymbaline (which began life as the nightmare sequence from their concept The Man And The Journey) was a live staple and the greatest advert for this album as a whole. Elsewhere, Crying Song established Gilmour as a solo guitarist on a Floyd album, and The Nile Song underlined the band’s rockier side.

As there was little budget, the band watched the film, timing sequences live, and then proceeding to record at Pye Studios in London’s Marble Arch, rather than their usual Abbey Road. At Pye, they worked for the first time with Brian Humphries, who would later work closely with them on Wish You Were Here and Animals. The film itself was a meandering tale of the naïve Stefan (Klaus Grünberg) who becomes entranced with Estelle (Mimsy Farmer), drops out and joins the hippie scene in Ibiza, before succumbing to the thrall of heroin. Floyd’s music is used sparingly yet effectively.

Their next film project was not as much fun. Zabriskie Point was Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni’s love letter to the collapse of the 60s, and as well as the Floyd, weapons-grade ambassadors of the counterculture such as Jerry Garcia and the Rolling Stones were on the soundtrack. Pink Floyd recorded a wealth of material in Rome for the soundtrack, much of which was rejected. Most famously in the Floyd canon, Rick Wright’s The Violent Sequence formed the basis of Us And Them from The Dark Side Of The Moon four years later.

The music choices, like most of their soundtrack work, sit outside their canon, especially Crumbling Land, which is the closest to Americana they ever came. As Floyd historian Stuart Shea notes, “Antonioni created a film depending on and celebrating empty space: musical, physical and emotional.”

Like the other ‘Floyd films’ of this era, there are few who will actually admit to watching it all the way through, yet its closing sequence is possibly the greatest of all Floyd links with movies. Female protagonist Daria (Daria Halprin) looks out across Death Valley as she visualises the residential desert development exploding repeatedly in slow motion, as Come In, No. 51 Your Time Is Up (a reworked version of Careful With That Axe, Eugene) plays out to spectacular effect.

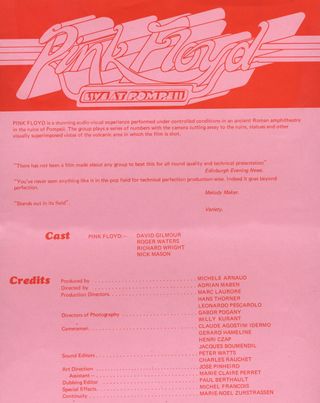

The music element of Floyd’s most famous film outing of this era – Live At Pompeii – is captured in full in the box set, edited to new 5.1 audio mixes, which means we’re spared the toe-curling canteen scenes and Rog twiddling his VSC3 over already recorded material. Directed by Adrian Maben, the film of the band performing without an audience in the historic Roman amphitheatre of Pompeii has become a cornerstone of their mythology. Live At Pompeii truly kept the band alive when their touring schedule slowed down. It was seemingly the choice of the late-night picturehouses for the whole of the 70s, often paired with Crystal Voyager (more of which later).

- The Making of Pink Floyd The Wall – the movie

- Pink Floyd: The Story Behind Atom Heart Mother

- Pink Floyd Quiz

- Pink Floyd to release ultimate box set The Early Years

Released in 1972 to accompany the film La Vallée, Obscured By Clouds is one of Floyd’s most straightforward albums and its meaty rock songs and plaintive ballads illustrate what could have happened to the group for the rest of the decade had Waters not thought so much. Working once more with Barbet Schroeder, the film again looked at the rejection of society for some form of countercultural nirvana. Set in Papua New Guinea, a French diplomat’s wife, Viviane (Bulle Ogier) sets off on an expedition, led by guru figure Gaëtan (Jean-Pierre Kalfon) in search of a mythical valley, with ultimately tragic consequences.

Pink Floyd convened at Château d’Hérouville near Paris, soon to be enshrined in pop legend by Elton John on the Honky Château album, and where the Bee Gees would later record their significant contribution to Saturday Night Fever. Here, as they had done with More, Floyd watched a print of the film and set about recording what was initially incidental music. Director Schroeder later told journalist Mark Blake: “[The band were] wonderful to work with. It was beautiful and fantastic music. The biggest present.”

The menacing title track is one of the rockiest things the group recorded, emanating out of Gilmour’s electronic VCS3 drone, with walls of guitar over Mason’s tribally influenced early drum machine-driven percussion. It certainly offered an alternative view of the Floyd. It was also – subliminally or otherwise – affectionately referenced on the frequently seen 1970s Denim aftershave commercial.

Free Four gave the group a toehold in the US, and saw Waters for the first time making explicit reference to the wartime death of his father (although Corporal Clegg from 1968 had alluded to it). The success of Free Four on FM radio opened the way for the success of The Dark Side Of The Moon. There’s a view that More and Obscured By Clouds are somehow not ‘proper’ Floyd albums. Not so. They’re the sound of a band with the pressure off.

After the success of The Dark Side Of The Moon, Pink Floyd invested their money in creating films to accompany their live performances. That didn’t stop their music being used in a variety of movies, most notably in David Elfick’s Australian surf documentary Crystal Voyager, written and narrated by surfer George Greenhough. Echoes plays out its full length under rolling waves, and the group were sufficiently impressed to use the footage to accompany the track onstage. Even controversial Polish director Walerian Borowczyk utilised a section of Shine On You Crazy Diamond in 1976 in the Sylvia Krystal/Joe Dallesandro vehicle La Marge (The Margin) to accompany a sequence in the film of oral sex.

There is, of course, a fifth major work later on: Pink Floyd – The Wall, which is a very different beast. Alan Parker’s imagining of The Wall has proved an enduring success since its release in 1982, mired in controversy, mainly because of the fiery relationship between Waters and Parker. British director Parker had risen through TV adverts and had enjoyed significant success with his films Bugsy Malone, Fame and Midnight Express. It wasn’t an easy relationship as both wanted to control the project. Eventually, Parker forbade Waters to join him on set on a daily basis in an attempt to stop him interfering. The film is just like the album: not for everyone, but if it is for you, the sensory overload, the bludgeoning by Gerald Scarfe’s animations, and the relentless attack of Waters’ lyrics make it an unparalleled tour de force. The Wall starred Bob Geldof as Pink, and charts with little subtlety his descent into mania. As difficult and as challenging as its parent album, the music is about as far away as possible from the mellowness that the group had become associated with.

Parker was subsequently to work with Peter Gabriel on the soundtrack of his film Birdy. Parker was initially reluctant to because of his time with Waters: “Peter’s not of that world,” Parker told Spencer Bright in 1988, recounting his experience on The Wall. “He’s a very different person. He doesn’t have any of the hang-ups or the unpleasantness of that particular business. We got on so well, he’s such a sweet man. It was a refreshing change.”

Aside from later concert films and the instrumental soundtrack to Nick Mason’s racing car showcase La Carrera Panamericana, there’s one last Floyd visual curio: The Final Cut, made to accompany the much-misunderstood album of the same name that was released in March 1983.

The band were wonderful to work with. It was beautiful and fantastic music. The biggest present.

Directed by Willie Christie, it’s fundamentally a long-form video. Over the course of 19 minutes, we follow the teacher from The Wall (Alex McAvoy) as he mourns the loss of his son in the Falklands conflict. We see a skewed attack on bingo-driven Britain in Not Now John and the teacher fantasises about assassinating the world’s dictators in The Fletcher Memorial Home. Waters himself, freed of any artistic constraints, makes a series of cameo appearances. As Floyd commentator Toby Manning has written, “There’s a ghost of something interesting here, though it’d require a séance to discover it.”

However, it will be the film work of their first seven years that will be most associated with Pink Floyd. Although seen often as stopgaps, the recordings act as a vital piece of the jigsaw, a prompt to what happened next. The palate cleansing of More took them away from attempting to ape Syd Barrett on an ever-diminishing parade of 45s, and Obscured By Clouds gave the group an opportunity to let their hair down in a short burst and deliver to order, something as a band they were never able to do again.

This writer interviewed David Gilmour in 2002 and asked him for his recollections of Obscured By Clouds. He said: “Good fun. Château d’Hérouville. We never categorised film soundtracks in the same way – that’s why they never make it on to collections.”

Well, with The Early Years 1965-1972, that has all changed. Now you have the chance to realise how vital a part they play in the legacy of the group.

Every Pink Floyd Album, Ranked From Worst to Best