Motorhead were formed by bassist/vocalist Lemmy in 1975, after he’d been kicked out of Hawkwind for allegedly doing the wrong type of drugs.

But Lemmy wasn't finished. He had a vision, to play the planet’s dirtiest rock’n’roll. So he formed Motorhead, and brought in drummer Lucas Fox and ex-Pink Fairies guitarist Larry Wallis. A deal with United Artists led to the recording of an album in 1975. But the label was so unimpressed with the results that they shelved the record, only releasing it in 1979 as On Parole.

By this time, Lucas and Larry had been replaced by Phil ‘Philthy Animal’ Taylor and ‘Fast’ Eddie Clarke respectively. But such was the lack of interest in Motorhead, the band were ready to quit, until Chiswick Records offered them three days’ studio time to do a farewell single. Amazingly, the trio did an entire album in that period, and the subsequent self-titled release did well enough to suggest there was a future for the band.

“Bronze Records then got in touch via our manager at the time, Doug Smith, and offered us the chance to do a single,” recalled Lemmy. “So we went into Wessex Studios (London) with producer Neil Richmond and did a cover of the classic song Louie Louie. It did OK in the charts [making it to number 68], so the label gave us the go ahead to make an album.”

Remarkably, the band went on to release two albums in 1979. Overkill came out in March, and was followed just seven months later in October by Bomber. This is the story of how those two classic albums were made.

Overkill

When Motorhead entered the studio at the end of 1978, it would be the first time that the band actually had the opportunity to do a proper studio record.

“Realistically, the Motorhead album was no more than a live recording. It represented what we were doing onstage at the time," said Lemmy. "But now we could actually stretch ourselves and see where it all led.”

The band decided to work with producer Jimmy Miller on the album. An inspired choice? Well, up to a point.

“It’s a long time ago now, but if memory serves me, we were given a list of four producers from which to choose – and the only guy on that list I’d ever heard of was Jimmy Miller, because he’d previously worked with the Rolling Stones. So that was the guy we went for.”

Jimmy was a recovering drug addict, and his problems with heroin in particular would come back to haunt the band when they subsequently renewed their working relationship for the Bomber album. But on Overkill, he was focused and positive.

“I know that Jimmy was never strung out for this project. He was happy and always smiling, and made a massive contribution. For a start, Jimmy knew his way round a studio, and as a band we certainly didn’t. He also became the fourth member of Motorhead for the time he worked on the album. It was a case of us being all in it together. We had to pull in the same direction to make it work – and Jimmy played his part to the full. It’s such a shame what happened to him.”

Jimmy died in 1994 at the age of 52 from liver failure, brought on through years of substance abuse.

Motorhead spent a six-week period from December 1978 to January 1979 in two studios, these being Roundhouse (where much of the recording was done) and Sound Development, both in London.

“We probably did about a six-week stint,” said Lemmy. “I suppose when you consider that we’d done the whole of the previous record in three days that’s a massive period of time. But what you also have to bear in mind is that this wasn’t a block of time in which we just concentrated on the album. We were also doing gigs. That’s the way things happened back then – it was far less regimented. However, we were all aware that studios cost a fuck load of money, so we weren’t about to waste our time.”

It was also an advantage that much of the material for the record had already been tested on the road; they’d been playing some of the songs for a while.

“Yeah, that helped to develop them. You’d be amazed the way songs change when you take them out on stage, so I suppose what we’d done – although not deliberately – was allow them to mature in a way that could never happen in the studio. But that’s an ongoing process. If you listen to the way we did Metropolis, for instance, on the record, it barely has any connection with what we now do live.”

The Metropolis song itself almost stands apart from the rest of Overkill, because it was written in haste, as the band tried to fill up space on the record.

“To be honest, we were one song short. So I had to come up with something literally overnight, I remember going to a cinema in Portobello Road (West London) that night; they were screening the classic Metropolis silent film from the 1920s [released in 1927], which was directed by Fritz Lange. That gave me the creative boost I needed. So, I went home, wrote the song, took it into the studio and we did it on the spot.

“One thing I do remember is that the guitar solo you hear on the song was the first take Eddie did – and he never even knew he was being recorded. Eddie was just tuning up when the tapes started to roll. And then he said, ‘OK, I’m ready to do the solo.’ We just replied, ‘Too late, we’ve already got it down!’ So, in a way what you hear on the album is just Eddie rehearsing and getting himself prepared. But, for us, he could never beat what he’d done first time. That’s what I mean about studios – you learn very fast what works and what doesn’t. We were all playing off each other.”

What you hear on the album is just Eddie rehearsing and getting himself prepared. But, for us, he could never beat what he’d done first time

Lemmy

The other interesting track here, from a production viewpoint is Tear Ya Down – what appears on Overkill is the original version done with Neil Richmond for the B-side of the Louie Louie single. So, why didn’t the band re-cut this with Jimmy?

“I could make up some rubbish about vibe and attitude, and how we could never match what had already been done,” laughed Lemmy. “The truth is that we couldn’t be fucking bothered. It just seemed like too much hard work to go back and re-do the song just for the sake of it. So, we decided to leave it well alone.”

All of the tracks on the record were written by the band, apart from Damage Case, where Mick Farren (an old friend of Lemmy) helped out on the lyrics.

“Mick wrote all of the lyrics at first, but then I improved on some of them, so what you hear is a collaboration between the pair of us, even though we never wrote them together.”

All of which brings us to the title of the album itself. To most people, this must have been something discussed by the band, and then unanimously decided upon. Wrong! The man who elected to call the album Overkill was…

“Gerry Bron, who owned Bronze Records. I have no clue why he wanted to go with this as the album title, but he put the idea into our minds. Maybe he heard something in the song itself, and that was a track that I’d named. I recall coming in with the idea for the song and just saying to everyone, ‘Right get your ears around this, you sons of bitches’. But Gerry gave us the title for the album.”

Now, some of the song titles here suggest weird and interesting stories – the sort that co-habit in sleazy bars and perverse alleys. For instance, there’s I’ll Be Your Sister – surely, this must be based on a very strange acquaintance from Lemmy’s past? Erm, well… that’s not the way the man himself recalled it.

“You know what, I’ve no idea where that title came from. Honestly, these things just pop into my head. It all comes from my imagination, which probably says a lot about me. At the time, it did make a lot of sense. But now… I really couldn’t say what I was on about!”

Much of what’s been said so far might suggest there was a certain chaotic logic about the whole Overkill process. However, things were a little more disciplined than might appear to be the case.

“Our working day in the studio began about two in the afternoon,” explained Lemmy. “And we’d work solidly through until about 10pm. Why did we knock off then? So we could get to the pub for a drink or two. Remember, this was back in the days before pubs could stay open as long as they wanted. They had to shut at 11pm.”

Overkill was released in March 1979, complete with a striking cover from artists Joe Petagno, the man who created the famed Motorhead logo. Yet he wasn’t satisfied with his work on the project.

“I had about a week-and-a-half to get it finished. But it was always a disappointment for me, personally. It should have been multi-layered. It was supposed to have a feeling that there was more to it – there were going to be more bits and pieces.”

Motorhead expanded their growing fanbase with this album. It reached number 24 in the UK charts, which, at the time, was a major breakthrough for the band. This was helped by the label’s cunning decision to release a green vinyl edition of the record just three weeks after it had first been issued in normal black vinyl, thereby ensuring that diehards would buy two copies.

However, marketing tricks weren’t needed to convince people that Motorhead had come of age. If its eponymous predecessor had been hastily, spontaneously concocted, then Overkill showcased a band growing on every level. This wasn’t just a rabble trying to play louder than anyone else, but three fine musicians proud of their craft. Now, it’s rightly regarded as a classic.

“Is it? I really don’t know!” said Lemmy, somewhat genuinely puzzled by the record’s undeniable stature. “What I hear is a record that’s… well, too slow! We play those songs much faster now. For us, it was a stepping stone, which led to Bomber – although I think Overkill’s a better record – and then on to Ace Of Spades. But what it did was prove we were a real band.”

Bomber

The pressure was on in that overheated summer of 1979. With Motorhead’s second album, Overkill, having just become their first UK Top 30 chart hit, Lemmy should have been skipping around in his dirty white boots. They had even been on Top Of The Pops – twice – and overnight they’d gone from being “the worst band in the world” (copyright NME, 1978) to the coolest rock band on the planet. Well, the coolest rock band in Britain, anyway. But instead of feeling pleased, Lemmy was fretting more than ever.

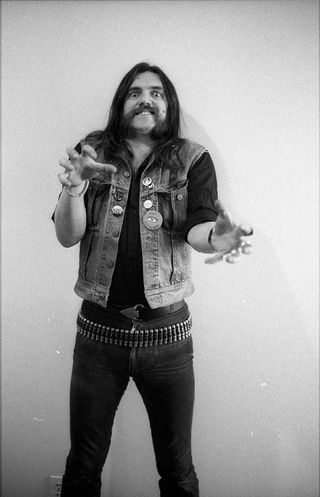

We were sitting outside a pub in Notting Hill, by the canal. A beautiful summer’s evening. But Lemmy was lost somewhere inside the darkness of his head. “It’s not like I’ve got any more money to spend,” he told me as I lent him another fiver. [He always paid me back, by the way.] We’re all still on forty quid a week. Only now they [the label] want another album out before the end of the year. They’re worried we’re a flash in the pan,” he growled. “I’ve been in bands for fifteen years. Had my first hit with Hawkwind in 1972. But the record company and the promoters still think it’s all just luck – and that we’re always about to run out of it. Fuck them.”

Lemmy always talked a good fight. But the truth is that he was backed into a corner. The recent success of the Overkill album and single had surprised everyone – including Lemmy – and now he felt that fear that all first-hit heroes feel when they’re expected to come up with an even better follow-up. Things would get better once they got into the studio and started work on a new album in a couple of weeks, I assured him.

“Well, it will keep us out of trouble, I suppose,” he said gloomily. He and the band had just returned from three days in jail in Finland, he elaborated. They had been arrested at Helsinki airport, on their way home from appearing at the Punkaroka Midnight Sun Festival. The festival promoters had gone to the cops after being horrified at the damage Motorhead had done to their stage. Lemmy had begun the show by offering the sizable crowd ‘peace and good vibes’ in Finnish, only to end the day by destroying all the equipment on the stage.

The real trouble started, though, said Lemmy, when drummer Phil ‘Philthy Animal’ Taylor had lobbed a tree into the dressing room – via a window pane Lemmy had just put his fist through. The band had then given said tree “a Viking funeral. We set fire to it and pushed it out on the lake. It was dusk, and it looked really great, you know. Then of course we got on the bus going back to the airport, and the driver made the terrible mistake of saying: ‘You will not make a mess on my bus’. Immediate food fight… When we got to customs, the official said: ‘Step into this room, please…’”

Having finally released after 72 hours of “being treated like shit”, and boarded their homebound flight, the pilot came storming down the aisle to inform them: “I’ve heard about you. You guys are a disgrace to society! If you do anything on my plane I’ll have the police waiting for you at Heathrow.”

But as soon as the plane took off, guitarist ‘Fast’ Eddie Clarke somehow managed to pour a very large vodka and orange down the neck of the female passenger in the seat in front of him.

“We didn’t think that was too bad, though,” said Lemmy. “But as soon as we got to Heathrow we saw all these police lined up on the tarmac! We thought:, ‘Oh no, we’re fucked here.’ But then they arrested the captain – he was drunk! Talk about poetic irony."

That had been late June. With their next show not until the Reading Festival in August, the rest of the summer was taken up with trying as fast as possible to make a followup to Overkill.

As if not to jinx it, recording was arranged, as with Overkill, at London’s Roundhouse studios, with producer Jimmy Miller again at the controls. Only this time Miller – whose heroin habit had already seen him fired by the Rolling Stones – was so out of it that Lemmy complained of finding him nodded off in his chair during playbacks.

“We used to think that we were bad at being late,” Phil Taylor later recalled, “but he would be, like, half a day late, or even more late, you know, and his excuses were marvellous.”

Uou never see me completely fucking out of it. You never see me falling all over the floor, puking up over everyone, being totally obnoxious, having to be carried home. I never get like that. How can I? I’m a speed freak. I’m up twenty-four hours a day.

Lemmy

Lemmy, who’d taken to yelling “Is everything louder than everything else?” mockingly at the producer before takes, said he always knew something was up whenever the hapless Miller failed to answer. Another time, Lemmy found Miller passed out in his car outside.

“I don’t know why I’ve got the terrible reputation,” Lemmy said. “I mean, you never see me completely fucking out of it. You never see me falling all over the floor, puking up over everyone, being totally obnoxious, having to be carried home. I never get like that. How can I? I’m a speed freak. I’m up twenty-four hours a day.”

Miller’s limited participation notwithstanding, the band powered through the sessions, working mostly on material they’d only just written, including the face-slapping opening track Dead Men Tell No Tales, a virulently anti-heroin song, clearly about Lemmy’s disgust at their errant producer. Over one of the best finger-jabbing riffs on the album, Lemmy spat: ‘Cos if you’re doing smack, you won’t be coming back/I ain’t the one to make your bail, dead men tell no tales…’

The fact that Lemmy was himself a virtual walking pharmacy, his battered leather jacket containing all manner of chemical sustenance in its many zippered pockets, didn’t make him a hypocrite, he explained. Nor the fact that he had been unfairly sacked from Hawkwind for, as he once put it to me, “taking the wrong drugs”.

“I don’t care what drugs people do,” he said. “That’s not my business. It only becomes my business if it causes them to start fucking me up. Which is what happened with Jimmy Miller.”

Lemmy chose speed over all other drugs, he said, because speed was “the only drug I’ve found that I can work on, and it’s helped me to be good. Not made me good – it doesn’t do that – but it’s helped sustain me being good when ordinarily I’d have been knackered and below par.”

But speed killed too, didn’t it? Or at least sent people doolally?

“Well, it does a lot of people. I seem to be lucky. I’ve got a nervous system that just eats it and goes: ‘Wah! Give me some more!’ So far I’ve got a mental and physical constitution like a rock – touch wood.”

The real problem with the album, Lemmy later admitted, was not which drugs the various principals were on, but the lack of space and time in which they had to work on the new material, some of which was being written on the spot.

“The difference this time was we’d never had a chance to play the new stuff live, like we had done on Overkill. If we’d had a couple of months of playing them live, that album would have been a whole better, less slick, more raw. Compared to how we play them live, the album sounds thin.”

Despite these drawbacks, the subsequent album, named after its best track, Bomber, remains one of the best-known that Motorhead would ever make. Built around more soon-to-be Motorhead classics like the ballistic opener Dead Men Tell No Tales, the slash-and-burn groove of the marvellous Stone Dead Forever, or, best of all, the anthemic title track, inspired by Len Deighton’s 1970 novel Bomber, with its fire-engine riff and double-fisted drums, Lemmy gurgling like a blocked drain over the top: ‘Ain’t a hope in hell, nothin’ gonna bring us down…’

That said, the rest of the Bomber tracks were of a more variable quality. As Lemmy later admitted: “There are a couple of really naff tracks on it,” citing Talking Head as his least favourite. A shame, as Talking Head boasted some of Lemmy’s best lyrics yet – an indictment of the pernicious power of television – but subverted by a tired, first-thought riff and underpowered production.

The album also featured one track, Step Down, with ‘Fast’ Eddie on completely unnecessary lead vocals. It’s a decent enough mid-placed blues, with some actually quite soulful guitar, heavily diluted by some dreadful lyrics (‘I ain’t no beauty, but I’m a secret fox’) and Eddie’s plain-Jane vocals.

Lemmy told me: “I got sick of Eddie moaning all the time about how I was the one getting all the limelight – me, the singer who formed the band and hired Eddie. How unfair! So I threw it back at him, saying: ‘Fine. You can sing this one.’ He was not happy. But he never asked again. Not that it stopped him moaning anyway…”

Lemmy would later accurately characterise Bomber as “a transitional album”. Tracks like the swaggering Lawman – Lemmy’s angry tirade against police harassment (from the Toronto drug bust that precipitated his firing from Hawkwind, to the most recent incarceration in Helsinki, via various police raids on his home and, most recently, the Motorhead office) – came with brilliant lyrics but music that only hints at the steeltrap snap it would later attain when played live.

Similarly, other plainly autobiographical tracks, like the ominous sounding Sweet Revenge or the scab-picking Sharp Shooter, both little-black-book entries of what Lemmy intended to do to all those who had wronged him (hello, Hawkmen); Poison, about his anger still at the way his father left his mother in the lurch when Lemmy was still a child, “horrible bald little fucker”; and All The Aces, about constantly being ripped off in the music business by ‘people who ain’t got faces’.

The lyrics are proper stories, drawn from real-life escapades. But the melodies and bang-bang rhythms are never developed, never arranged properly, never fully produced. The result is a sludgy sameness that sounds like a dead body being dragged from a river.

As Eddie recalled for me just a few months before he died: “The way Lemmy’s lyrics had improved was amazing. For fuck’s sake, he was improving all the time. Once we’d cracked the little formula of how to really work together on Overkill then we really started to take off. Then Bomber was fucking… I dunno. Some great tracks, great lyrics, some good riffs, but the overall thing came over a bit flat after Overkill.

“None of us in the band were really happy with it. It didn’t feel quite right, like it wasn’t all there. It might sound strange coming from a band that prided itself on the speed with which it made records, but the whole thing was just done too fast. I don’t think any of us heard the whole album properly till we had finished copies in our hands.”

There were, however, two absolute stone-cold killer Motorhead tracks on Bomber. The first, Stone Dead Forever, was one of the greatest things the original three amigos line-up ever did. Built around the same single-note distorted power drone on Lemmy’s bass as on the Overkill single, Lemmy gasping out the lyrics, Eddie bringing everything to boiling point with the best, most sensual guitar part he would ever come up with, Stone Dead Forever was immense, a monumental classic, part punk, lots of metal, total Harley-Davidson.

“I mean, Stone Dead Forever,” said Eddie, squinting at me, still shaking his head in disbelief nearly forty years later. “Like, fucking hell! Did I really play that guitar?”

The best, though, they saved until last, almost as a reward for hanging on in there. Featuring that now famous air-raid siren riff, bugling lead guitar and scattershot drums, and with Lemmy growling like a sheep-killing dog, Bomber’s title track would instantly become one of the unholy trinity of all-time Motörhead classics, along with Overkill and Ace Of Spades.

Although Lemmy nicked the title from the Len Deighton novel, the lyrics had nothing to do with the original plot in which an RAF Second World War bombing raid in Germany goes wrong. Instead, Lemmy used the imagery of the Lancaster bomber soaring overhead, releasing its deadly payload, as the lynchpin for a metaphorical exposition on life on the road in an outlaw rock’n’roll band. ‘Because you know we do it right, a mission every night/It’s a bomber, it’s a bomber…’

Cue absolute mayhem. Especially after the band took the album on the road later that year, and showed off their new stage-prop: a 40-foot aluminium-tube ‘bomber’ that appeared to divebomb the audience from the stage.

In actuality it was a specially designed lighting rig with four ‘engines’ that moved backwards and forwards and from side to side, its guns firing as it swooped down as though about to crash into the audience.

Eddie always said it was he who came up with the idea. The way he told it, all three of the band were sitting in the office one day, across from their then-manager Doug Smith, “talking about a way of incorporating plane wings into the stage set. But it was really a bit far-fetched.”

Then their lightning guy Peter Barnes came up with the lighting truss idea. According to Eddie, “He said: ‘Why don’t we put the lights on a fucking bomber truss. And then put it on chains and move it up and down.’ I thought, steady fucking on! But we tried it, and it worked. Really worked! The Bomber set was a step up, definitely.”

In today’s world of computerised stage productions, where dancers and video screens provide as much entertainment – often more – than the music itself, it’s hard to imagine the excitement and astonishment that greeted Motorhead’s relatively simple new Bomber stage show.

This was more old-time circus than mod-cons CGI, but the photographs that now peppered music magazines all over the world and the column inches it also helped generate meant the Bomber show really helped spread the message that Motorhead were now far beyond the usual punk-metal bash. That what they were doing now was on another level. Still of the street, but looking up from the gutter at the sky. Class in a distinctly no-class way.

“If you were having a bit of a bad one,” said Eddie, “you’d think: ‘Thank god the Bomber’s coming next number.’ You knew damn well that once that thing come down it killed everybody!”

The first Motorhead album to feature pictures of all three members on the cover – pictured in bomber-command mode aboard a fantasy firebird created by famed sci-fi illustrator Adrian Chesterman – Bomber was released on October 27, 1979.

Initial pressings were on blue vinyl and sold out immediately, sending the album straight into the UK chart at No. 12 – the band’s highest chart placing thus far. When the track Bomber was released as a single five weeks later, again initially on blue vinyl, all 20,000 copies sold out within a week, taking the single to No.34. (Quick comparison note: if a single sold 20,000 copies in 2019 it would go straight to No.1.)

There was also the reward of another appearance on the nation’s favourite weekly TV chart show, Philthy Animal chewing his tongue at the front in a gangster’s hat (they always used to put the drummers at the front on Top Of The Pops because often they were the only ones in a group that was miming who really moved); Lemmy in blackout mirror shades; Fast Eddie, eyes screwed shut, back-handing his guitar; the clearly dumbfounded audience in their nice jumpers just sort of standing around in front.

All those TV appearances and magazine covers had now turned Lemmy, Eddie and Phil into unexpected stars. By the start of 1980 their weekly wages had now been upped to £200 a week, and suddenly their lives were changing.

Doug Smith recalls organising a £10,000 publishing advance for each member. “They were all going to buy a house with it. Once they’d found a place, we’d give them the ten grand each, so it didn’t go anywhere else. Eventually Eddie bought a place in Chiswick. Phil bought a place in Chelsea. And Lemmy still hadn’t looked for anything.” Then Doug arranged some appointments for him.

“The first one he went to, the woman opened the door, screamed and slammed the door in his face. That was the last time Lemmy looked for a place to live.”

But he didn’t need to. For the next three years Lemmy pretty much lived on the road. A new mission every night, as he sang on Bomber. Until one day…

Overkill and Bomber are released together as a limited-edition, 40th anniversary box set. For more information, and to purchase limited edition bundles, visit the Motorhead 1979 website.

Below, Orange Goblin frontman and Motorhead fan Ben Ward unboxes the Motorhead 1979 set.