On an otherwise indistinct evening in 1953, viewers tuning in to their local TV station in Jacksonville, Florida were treated to the rare sight of a cherubic three-year-old boy playing the banjo like an old timer. During any given week, the Toby Dowdy Show served up to Florida residents a wholesome diet of down-home light entertainment, presided over by the titular host, a genial-looking fellow in a rhinestone shirt. A musician himself, Dowdy welcomed onto the air the popular country and bluegrass players of the day: guys such as Roy Rogers, the singing cowboy who brought along his horse Trigger, and Tex Galloway and Shorty Medlocke. A fixture in Dowdy’s house band, the grizzled Medlocke had a particular interest in how the kid with the banjo went over that night, since he was little Rickey Medlocke’s granddaddy and had encouraged the lad to play.

“Shorty got to play with all of the legendary Nashville cats of the time,” Rickey Medlocke recalls today from his waterfront home in Fort Myers, Florida. “He played a lot of different instruments – five-string banjo, guitar, dobro, fiddle, harmonica and mandolin. Not only that, he was also able to play them incredibly well. He taught me three chords – G, C and D – and then told me to learn the rest on my own. I guess he knew that growing up around all the musicians in his band I would grasp it pretty quick.

“One day Shorty was telling Toby Dowdy how well I picked banjo and would sing along with him. Soon as Toby heard of my age, he shot back: ‘Well, I find that pretty incredible to believe and need to see it for myself.’ Shorty worked up a song with me for the show, and I got to don a little cowboy outfit just like his for the broadcast. And hell, all the week after, mail just poured into the station. Toby had me back for the next five years until his show went off air.”

For Rickey Medlocke, that first public appearance began an odyssey through music that has been running for 63 years now. Twice he has been a member of Lynyrd Skynyrd, the greatest band to have emerged from the Florida wetlands. He also led his own much-loved group, Blackfoot. Along the way he’s enjoyed platinum-selling records and adoring audiences, and experienced his share of loss, rancour and despair. Today, his arms a tapestry of tattoos, his hair long and now the purest white, he still looks every inch the rock’n’roller. His voice, though, a rasping husk, betrays the wear, tear and scars of all those hard miles travelled.

“Thinking back makes me feel more like I’m ninety-six years old,” he says, laughing. “But I’ve sure enough had an incredible life. And I have been blessed to stand on stage next to some of the world’s greatest musicians. You know, it just don’t get no better than that.”

Rickey Medlocke’s mother had just turned 16 when she gave birth to him. His biological father, a Native American by blood, didn’t hang around to bring the boy up, and the child would have been given over to the orphanage had his maternal grandfather not intervened. Shorty, who was of Scots-Irish descent, and his second wife, Ruby, legally adopted Rickey and raised him as their own.

He was a precocious kid and, as a result of his grandfather’s influence, enthralled by music and musicians from just as soon as anyone could remember. Yet it wasn’t his appearances on TV that sealed the deal of his future life, but an encounter he had three years later. On occasion, Rickey would be babysat by a friend of his grandparents, a bubbly blonde Texan lady named Mae Axton, who also happened to be a prolific songwriter. It was on account of one of these tunes, co-written with local steel guitarist Tommy Durden, that Mae managed to have a meeting with the new swivel-hipped singing sensation of the south, Elvis Presley, when he came to town during the sweltering August of 1956.

Axton and Durden got to play their song for Elvis and his manager, Colonel Tom Parker. Both were impressed, but the indomitable Parker drove a hard bargain. Elvis, he said, would record the song, but only in return for a writing credit and half of the publishing. Axton and Durden agreed. Which is how Elvis secured his breakthrough hit, Heartbreak Hotel. As a gesture of gratitude, Parker handed the visitors two pairs of tickets for Elvis’s matinee show at the Jacksonville Theatre that evening, August 10.

“Now, Mae knew well that I was already a music nut so she gave my folks three of those tickets,” says Medlocke. “We were sat centre-stage, five rows back, and when the freaking King came out I just about flipped. Driving home that night, Shorty looked over at me in the back seat and asked: ‘Well, son, what did you think on all that?’ He and Ruby would always remember how I stared wide-eyed back at him and said: ‘That’s what I want to do.’”

So inspired, by the age of eight Rickey had also mastered guitar and drums. And when the drummer in Shorty Medlocke’s band quit later that same year, Shorty gave his grandson the job. Rickey beat out a rhythm for his old man for the next 10 years, and fronted a succession of other fly-by-night combos through high school. Long forgotten, these were haphazard collectives with names such as the Candy Apples, the Sunday Funnies and the Miracle Sounds, and they doled out a mixture of blues, rock’n’roll and R&B standards. The tentacles of the 60s counterculture also got to reach Jacksonville, and Rickey Medlocke fixated upon three guitar wizards from England: Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck, each of whom had gone on from The Yardbirds to stir heavier, more potent and stranger brews.

“I took to Clapton especially,” he notes. “He had a real blues feel to his playing, but also heavy rock, and what he did with Cream still blows my mind. Jacksonville was a conservative place, pretty much a navy town, but there were also a lot of talented musicians around the place at that time, and particularly playing my grandfather’s kind of music. In hindsight, right then, as far as music goes, we got to live through a magical period.”

Upon graduating, Medlocke formed his own band with two fellow budding musicians he’d met on the Jacksonville circuit, guitarist Charlie Hargrett and bassist Greg T. Walker. An Italian kid, Ron Sciabarasi joined them for a while on keyboards and together they took their name from Fresh Garbage, the opening track on American psych-rockers Spirit’s self-titled debut album of 1968. Medlocke initially drummed and sang, but in no sense were Fresh Garbage’s beginnings auspicious. Having exhausted their opportunities at local clubs they got a gig, a residency at a topless bar, just down the road in Gainesville. Sciabarasi had by then been replaced by a DeWitt Gibbs, who brought along with him Jakson Spires, the drummer from his previous band. Spires’s arrival allowed Medlocke to move fully up front.

Newly configured, the group managed to impress a visiting New Yorker with connections to the music business. Encouraged to head north, the quintet packed up their trailer and upped sticks to an apartment in Greenwich Village, changing their name on the way to Blackfoot, in recognition of their shared Native American ancestry. However, a promised record deal didn’t materialise and the band were soon floundering and at each other’s throats. Dejected, Medlocke rang an acquaintance back in Jacksonville, Allen Collins, guitarist with fledgling local heroes Lynyrd Skynyrd.

“I reached out to Allen for advice more than anything,” Medlocke explains. “First thing he said to me was: ‘You need to call up Ronnie right now, because Bob Burns has just left the band and we need a drummer.’ I got right on the phone with Ronnie, and he told me that in two weeks they were going down to record at Muscle Shoals in Alabama. They sent me a plane ticket, I sold off a couple of amps to get some money and a week later, I was sitting in Skynyrd’s rehearsal place in Jacksonville.”

By 1971, Lynyrd Skynyrd had been honing their sound – a rich gumbo of southern-fuelled rock and blues founded upon the interweaving guitars of Collins and Gary Rossington – for two years. In this and all other matters, singer Ronnie Van Zant was the band’s self-appointed leader. And he ruled with an iron fist, insisting upon a strictly disciplined regime of rigorous rehearsals that drilled the group into a formidable unit, one that had taken the Jacksonville scene by storm. When Medlocke joined, Van Zant was plotting Skynyrd’s breakout to a national audience, the first stage of which was the imminent week-long session at the fabled Muscle Shoals studio scheduled for late June and July.

Opened in 1967 on land bordering the Tennessee River, Muscle Shoals had already hosted landmark sessions by Aretha Franklin, Wilson Pickett and the Rolling Stones. It also had a crack house band, the Swampers, whose guitarist Jimmy Johnson was booked to produce the Skynyrd recording. Medlocke had a familiar face accompany him on the journey. On the eve of their departure for Alabama, bassist Larry Junstrom quit the band and Medlocke angled to have Greg T Walker fill in for him.

Over four days from 28 June, this line-up cut the original versions of the classic Free Bird and I Ain’t The One, both of which would subsequently be re-recorded for Skynyrd’s trailblazing 1973 debut album. Among other tracks, they also laid down a couple of Medlocke-penned and sung songs – The Seasons and folksy lament White Dove – plus another brace of propulsive tunes he’d co-written with Van Zant: Wino and Preacher’s Daughter.

“We were all into Neil Young back then, and the guys thought it added to the band that I could also play acoustic guitar and had a real high-pitched voice,” he reasons. “And maybe Ronnie did rule with an iron hand, but he and I never had a moment of confrontation. I found him a very open-minded guy. He would let me take over the mic whenever a song suited my voice. And, my God, in four years under his leadership look at what they went on and accomplished.”

Medlocke, though, was no longer with Skynyrd when they went supernova. Itching to return to frontman duties, he and Walker had instead revived Blackfoot with Hargrett and Spires. Edging towards a harder version of the Skynyrd blueprint, both of Blackfoot’s first two albums – 1975’s No Reservations and the inaptly titled Flyin’ High from the following year – sank without trace. By 1977 they were again butting their heads against a brick wall. Kicking his heels back in Jacksonville one day that summer, Medlocke readily accepted an invitation from Van Zant to go and hear Skynyrd’s just-finished new album, Street Survivors.

- The 10 Essential Southern Rock Albums

- Why Southern Rock Is Exploding Worldwide

- The Top 10 Cult Southern Rock Songs according to Johnny Van Zant

“Ronnie really wanted me to listen to a song that they had put on the record called One More Time, which we had done at Muscle Shoals,” Medlocke remembers. “And as I was getting ready to leave, he said to me: ‘If you’re not doing anything right now, why don’t you come along on the road with us? We’ve got our own plane.’ I was all for it. But as fate had it, Blackfoot ended up getting two weeks of dates just as Skynyrd were set to go out on tour.”

Just as Skynyrd’s plane took off on its last, fateful flight from Greenville, North Carolina on October 20, Blackfoot pulled into the upstate capital of Columbia for a show. During their gig that night, a stage hand shouted out the news of the plane crash. Medlocke was distraught.

“Soon as we finished our show, I hauled ass back to our hotel and dialled my folks,” he says. “The phone didn’t even ring out once. Shorty picked it up and I begged him to tell me it wasn’t true. He said: ‘No, son. It’s true alright, and they just announced on the TV that one of the victims was Ronnie.’”

Blackfoot soldiered on. And early the next year found themselves a manager, Al Nalli, who worked out of the same car-making city of Ann Arbor, Michigan that Iggy Pop and the Stooges came from. Nalli had managed another of Ann Arbor’s rock bands, Brownsville Station, and in 1973 had guided their Smokin’ In The Boys Room single to No.2 on the US chart. Under Nalli’s direction, Blackfoot signed a new record deal and then set about making their third album, Strikes, in his basement studio in Michigan. Nalli made a virtue of the rough, unadorned edges of their sound, and Strikes went on to sell a million copies, urged on by a hit single of their own, Train, Train, a slide guitar-led boogie-fest written by Shorty Medlocke.

“How important was Al to us? Well, he’s still my business partner to this day,” says Medlocke. “Just recently I dug out a great picture of us making that record at Al’s place. That was back in my crazy-ass days and we just drank non‑stop. On the tapes we could hear this weird, rattling sound, which none of us could figure out. Turned out it was coming from all of the empty beer cans that in the photograph you can see littered the floor.”

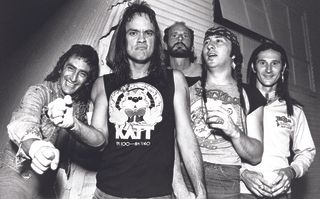

Strikes was followed by Tomcattin’ and Marauder, a further pair of biting records off the back of which Blackfoot also built a reputation as a ferocious live band. Their no-nonsense appeal crossed the Atlantic too, their passage eased by a barnstorming appearance at the second Monsters Of Rock festival at Castle Donington in August 1981.

Yet as the decade wore on, their fortunes waned. Soon enough, southern rock was deemed passé and the advent of MTV pushed the band towards a more refined sound, a change signalled by their ill-fated decision to bring former Uriah Heep keyboard player Ken Hensley into the line-up.

“What I regret most is that we allowed the damn record company to make us conform to what was then supposed to be popular,” says Medlocke. “We shouldn’t have ever had a keyboard player in the band. We should have said fuck it and stuck to our guns. But business, money and personal feeling also got in the middle of us.”

As one flop album followed another, the bad blood that had begun to fester – occasioned by a sense among the others, and Hargrett in particular, that Medlocke had taken over – bubbled up to the surface. Hargrett walked out in 1984. Not long after, Blackfoot hit the rocks.

“Until then I had not realised that one certain party harboured such animosity towards me,” Medlocke insists. “But that tore the four of us apart and broke my heart. I mean, Jack and I especially were so tight at the time. He had married my sister, so was family. No one of my parents, relatives or friends could believe that the two of us went our separate ways.

“Last time I spoke to Jack was in March 2005. He was in a hospital bed and on life support. He’d had a massive brain aneurysm and I didn’t know if he could hear me or not, but I asked him to always remember that I loved him dearly and that he was my brother, and I said that I was sorry how things had turned out. Next day he was gone.”

The ensuing years were long, hard and bleak for Medlocke. He tried to keep the Blackfoot name alive, surrounding himself with an ever-changing cast of musicians, but he never got close to capturing former glories. And then, in 1996, he took a call from Ronnie Van Zant’s widow, Judy. Skynyrd had been resurrected in 1987 with Ronnie’s brother, Johnny, stepping into his shoes, and now a movie about the band, Freebird, was due to premiere in Atlanta, Georgia. Judy wanted to know if Medlocke would attend.

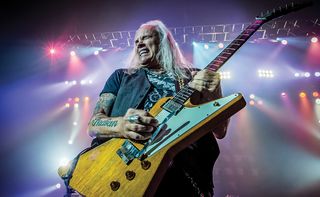

“I said: ‘Hell, yeah,’” he enthuses. “The night before the premiere, they had an all-star jam down at the Fox Theatre in Atlanta. I walked out on stage by myself with an acoustic guitar and played Blackfoot’s Highway Song solo and got a standing ovation. Not long after, I picked up a message from Gary Rossington on my answer machine. He said he was going to fly right on down to audition me to play guitar for Skynyrd, and if I passed he would give me a quarter dollar and a Snickers bar.”

Medlocke duly made his return to Skynyrd, and right on up to the present his guitar has rekindled both on record and stage the fire sparked by his late compadre, Allen Collins. In more recent years the band have lost two more core members: bassist Leon Wilkeson in 2001 and pianist Billy Powell in 2009. Today Medlocke sees it as a duty for Rossington, Johnny Van Zant and himself to keep the Skynyrd flag flying in their honour, and also that of Collins, who died back in 1990, and of those who perished on that October day in 1977.

“From the moment I was back in the band, I told Gary that I would ride with him all the way to the very end,” he says. “It’s important to me because those guys created some incredible music. Just as you would imagine, we’ve gotten beat up about this not being the original band, and of course it’s not. But if it’s got Gary, Johnny and I in it, then it is Skynyrd. We were there at the beginning, and come the day we’re not around, believe me, people are gonna miss us.”

Medlocke has applied the same kind of logic to preserving Blackfoot’s legacy. One time he was dragged through the courts by Hargrett, Walker and Spires to determine who had ownership of the name. He lost it for a while, but was then able to claim it back. In 2015 he got approached with the novel idea of allowing Blackfoot to be used once more, but by a fresh crop of Jacksonville musicians. Medlocke consented, but on the condition that he maintain a background role as songwriter and producer for the otherwise all-new four-piece band. Southern Native, the debut album from this new incarnation of Blackfoot, released in August 2016 and overseen by Medlocke, recalls the undiluted spirit of their forefathers.

“The boys opened up for Skynyrd not long ago, and somebody posted online a picture of me watching them from the side of the stage,” Medlocke says. “Written underneath it said: ‘The proud papa of a brand new baby.’ And I really am. And as for it being Blackfoot, well then, my involvement keeps it legit.”

Right now, though, Rickey Medlocke, 66 years young, has Skynyrd business to attend to, with live dates across the US stretching to the end of the year, and beyond that to who knows when. He fixes his eyes on the road ahead, bids the fond farewell of a true southern gentleman and then offers a parting shot: “When all’s said and done, man, I’m just like the cars that I drive, which is to say built for speed and balls-to-the-wall.”

Rickey Medlocke’s 5 essential guitar albums

Lynyrd Skynyrd: The Heartbreaking Story of an American Legend