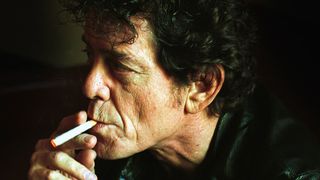

Lou Reed’s reputation preceded him.

Being ushered into his presence in a bare, anonymous meeting room in the offices of London’s Capital Radio on a bleak February day in 2004 was fearfully intimidating. I’d heard all the stories: of tape recorders thrown at walls and hard-nosed hacks reduced to tears. My head was expecting the worst, but my heart was hoping for the best.

Lou Reed was my idol, the measure of all that a catalyst, musician and songwriter could or should be. He’d entranced millions with Perfect Day, broadened minds with Walk On The Wild Side and expanded rock’s parameters with the Velvet Underground. I knew that I was risking an enormous amount by placing myself in his firing line. If he chose to gleefully tear me to pieces – as received wisdom told me he surely would – I risked never being able to listen to his music again without it being forever tainted.

But I had to interview him. How could I not? After all, it was the critical drubbing accorded his 1973 masterpiece Berlin that caused me to first realise the gentlemen of the music press were not only fallible, they needed replacing… by me.

So, like a lamb to the slaughter, I took my seat and prepared to go head to head, across the most insubstantial of trestle tables, with the Rock ’N’ Roll Animal himself.

Opening with a possibly foolhardy question regarding his less than contemporary doo-wop work of the late 1950s, I was gratified that he not only elected to address my question with courtesy but also neglected to offer any indication of withering contempt. I offered a second cautious question for his perusal and unexpectedly entered the arena of the miraculous.

Lou was aware of my work. He’d read a review I’d written of his NYC Man compilation and, unbelievably, had actually liked what he’d read. From that moment on, it became abundantly clear that he was going to answer all of my questions, even the tiresome ones about David Bowie and Andy Warhol that he usually sidestepped.

When I spoke cobblers he gently corrected me without spite. In fact, all outward indications seemed to suggest that we got on.

In the decade that’s passed since that initial encounter (which only concluded because Lou was determined to buy himself a new watch before the Bond Street shops closed), I spoke with him on four further occasions and it was always a pleasure, never a chore.

His death left an irreplaceable void where mainstream, avant-garde and alternative rock’s Venn diagram intersects. Since then I’ve read way too many grudging obituaries written by people who never met him, serially accentuating what a ‘difficult interview’ he was.

All I know is that the Lou Reed I met was neither irascible, curmudgeonly nor aggressive.

He was someone else… someone good.

What can you remember of your first recording?

When I was in high school we had a band and it was originally called The Shades. Me and these two other guys. I wrote the songs and sang in the background. I wasn’t upfront. At the same time there was a group from East Meadow, Long Island, called The Bellnotes and they recorded a song called I’ve Had It. I’ve Had It became a regional hit; my songs: nothing, zero. So then [radio DJ] Murray the K was supposed to play our song one night, but he was sick and his replacement did. I actually heard my song on the radio when I was 14, my own song, once. That was it. And I received a royalty check for two dollars and 49 cents, and that was that.

When did you first recognise a flair for creative writing, and was writing music initially a vehicle for the written word?

You wrote a really nice review of the compilation, didn’t you? Well, I normally don’t read these things, but I was told: “You have to read this, you have to read this.” And I want to thank you for that. It was very nice of you to put something like that into words, normally people don’t. It’s much easier to be negative.

Anyway, I studied classical piano, and the minute I could play something I started writing new things. And I switched to guitar and did the same thing. And the nice thing about rock is, besides the fact that I was in love with it, anyone can play that. And to this day anyone can play a Lou Reed song. Anybody. It’s the same essential chords, just various ways of looking at them. There is nothing special about it, and it only becomes special when I can’t do it. When I can’t do it I’m very impressed by the person who can, and when I can do it it means nothing. But I would write new things from the day I could play anything.

How did you become involved with Pickwick Records in 1964, and what do you remember of that period?

I was looking for a job and got a job as a staff songwriter at a real pittance. And it was great experience. It was just me and these three other guys writing essentially what would be called hack stuff. And a lot of that stuff has found its way onto bootlegs, amazingly enough. Psycle Annie is an example of that kind of thing. But there was one that I really liked that I wrote with one of those guys called Love Can Make You Cry, and I’ve never been able to find a copy of that. That actually was a good song. Psycle Annie, that was one of those hot-rod songs. And I wrote another one: Let The Wedding Bells Ring. Have you heard that track? Well, the guy’s got a car in high school, she wants to get married, he doesn’t have enough money so he enters a race, and gets killed. So, you know, they came in the room and said: “Write us 20 rock’n’roll death songs…” You know, Tell Laura I Love Her, those kind of things. So we did. And it was a great experience because you got to record them… The writing is nothing, but it’s like training. I’ve only had two or three real jobs in my life. None of them lasted very long. But one of them was to file the burr off a nut in a factory, and that’s what this was.

When you first met John Cale, were you already aware of his work with the Dream Academy?

No. What happened was that I wrote a song called The Ostrich, and they decided that they wanted to have a group say they did it. Because it was just me and the other three guys who did it. And I’d taken a guitar and tuned all the strings to the same note. I did that because I saw this guy called Jerry Vance do that. Jerry Vance was not an advanced avant-garde guy, he was just screwing around. And he didn’t realise what he had. But I did. And I took that and made it into The Ostrich. Then they wanted to have a group to say that they recorded it, called The Primitives. So this guy went out to a party to find people with long hair and he brought in Cale. He brought in Cale, Tony Conrad and Walter De Maria; they were all artists. You got in fights in those days if you had long hair.

How did the Velvet Underground come to the attention of Andy Warhol and what did you make of him when you first met?

[Lou smiles] These are questions that you have dreamed of forever to get a chance to ask… I loved him on sight, he was obviously one of us. He was right. I didn’t know who he was, I wasn’t aware of any of that, amazingly enough. But he was obviously a kindred spirit if ever there was one, and so smart with charisma to spare. But really so smart. And for a quote ‘passive’ guy, he took over everything. He was the leader, which would be very surprising for a lot of people to work out. He was in charge of us, everyone. You look towards Andy, the least likely person, but in fact the most likely. He was so smart, so talented and 24 hours a day going at it.

Plus he had a vision. He was driven and he had a vision to fulfil. And I fit in like a hand in a glove. Bingo. Interest? The same. Vision? Equivalent. Different world, and he just incorporated us. It was amazing. I mean, if you think in retrospect, how does something like that happen? It’s unbelievable. I went from being with Delmore Schwartz, who taught me so much about writing, and then I’m there with Andy where you get all the rest of it.

Right place, right time, on two occasions, both within a very short space of time.

Very hard to believe. I mean, you know, it’s not something that you would want to bet on, or plan on. On the other hand, that’s where it cast my lot; I would survive on making things. So, in that sense, I was there. I was available. Did anyone notice? No. Did anyone care about us? No. And then who walks in? There you go. Opportunity of a lifetime.

Were you initially enthusiastic for Nico to work with the band?

You know, Andy had a vision, and he had this way of looking at it. “Have a chanteuse.” Why not? That sounds like fun. What, are we hard-core or something? We were very hard-core about the music and the lyrics and the approach, but the rest of it, it was like he was a god-send, just amazing. He did everything. You know, protection; we were so nothing, what was there to criticise with us? No one ever heard of us; you can’t criticise a zero, you know. So they criticised him. He could care less. I watched. I watched everything he did, and I studied everything he did, and I really listened to him because he’s so smart. But I mean smart and does things, not just theoretical smart, like smart and he’s right out there. Pretty admirable: one idea after another.

People were like: “How can he produce the record? He’s not a musician.” Well, first of all he pulls me aside and he says: “Whatever you do, don’t clean it up, don’t slick it up. Don’t clean it up, don’t let them change anything, do it exactly the way you’ve been doing it.” And he made sure that happened, because he was there. I mean, they wouldn’t even talk to us. They talked to him. They said: “Mr Warhol…” blah, blah, blah, and he would say: (adopts uncannily accurate Warhol voice) “Oh, that’s great.” And that would be that.

They’d look at him, because however strange they thought us or we were, Andy with a silver wig? Right to the head of the class, you know. And he would be really, really aggressively fey on purpose. You know, really push it at them. And if you look at pictures where everybody posed for pictures, Andy would do something really odd or something, so you look at that picture you have to look at him. And when you were with these people they had to go to him; none of us were wearing a silver wig.

He was his own greatest creation: his own work of art.

He was a magnificent creature, and he really thought about it. Just look at the way he was before he switched over from commercial art. It’s one of the great ideas, and boom, he just goes and does it. And he would put his money where his mouth was: all the movies, the this-and-that, were funded by him out of his own money. And he wasn’t getting anything back out of it. When I left, I just left. He didn’t say, ‘Hey, I’ve done this and that for you, I want 20 per cent forever,’ or anything. He was really noble.

In the NYC Man sleeve notes you say that “you could have the IQ of a turtle and still play a Lou Reed song”, in reference to Heroin. Though it is basically three chords, the great drama of its dynamic transcends the recognised constraints of the straightforward rock’n’roll form.

It’s actually two chords and I’m being funny. But yeah, the turtle could do a really stupid version of it. But that’s like saying that an idiot could say Terry Malloy’s speech in On The Waterfront; any idiot could say: “Charley, it was you, Charley. Charley, it was you, I could have been somebody, Charley.” Anybody could say that. Brando, though, that’s another story. So it’s the way the artist presents it. That’s the defining moment.

You also seem compelled to reinvent your work. On the Rock’N’Roll Animal tour you seemed to accentuate Heroin’s inherent drama yet further.

Well, I had a lot of time to think after the Velvet Underground broke up and here were these songs of mine. And then I heard Mitch Ryder’s Detroit Wheels, produced by Bob ‘Wonderboy’ Ezrin, doing Rock And Roll and I said, “Aha, that’s fun.” So Ezrin got Alice Cooper’s band for me. I can’t play that way, I don’t wanna play that way, but they were as good at ‘that way’ as anybody else around. So I said, “Okay, here’s the material.” They didn’t know it from the Velvet Underground, they’d never heard it, so I just taught them the whole thing. Now we’ll try it again, see what happens five years later. Duh. Let’s see if they [the record-buying public] get it this time around. Change the presentation. I mean, it is not something that I would want to keep doing, but it was probably one of the greatest live records ever made. So there you have it.

And, my God, how it works. It positively sizzles. The first time I heard that version of Heroin it was the full hairs-on-the-back-of-the-neck deal. Which is what you want.

Well yeah, this is rock. There is supposed to be a physical and mental reaction to this, and if you don’t get that what are we doing? There’s all kinds of other music to fall asleep to and relax to, but this is supposed to be visceral. This is really physical music.

The Velvet Underground seemed to be the direct antithesis of the flower-power movement then prevalent in San Francisco and subsequently the world?

Well, we were also really, really smart, and the other stuff was really, really stupid. And as people get older and wiser and can start differentiating, they say: “Woah.” That’s if they get a chance to, of course. At this stage you’ve got to know about it to find it, and, at that time, it was purely a matter of brains. I mean, there are people who voted for Bush.

When you returned to the original masters for NYC Man, were you finally able to address problems with the sound that you’d previously thought unsolvable? For example, you mention in the sleeve notes how you were able to accentuate John Cale’s piano in I’m Waiting For The Man. And it does work, it kicks that arse.

Oh yeah. I mean, that is part of the mastering thing. I know how it is supposed to sound, and I know what it is supposed to do. If it doesn’t do that on the CD, the mastering hasn’t been good. So we went back and I said, “I want it to do this, this, it’s in here, and there it is.” But along with that, you can bring in a lot of space and air and push. It’s very, very interesting, just mastering correctly. I think all artists should, really, before their tapes completely oxidise and disintegrate. Because the record companies don’t care, it’s not like they’re taking care of these tapes. They’re not taking care of these tapes, these tapes are sitting in a warehouse, oxidising away.

So it behoves an artist, if he can. And in my case, the only reason I could is the guys at BMG had this idea. And it involved two other companies to get them to cooperate, so you had an overall view of things. And I’d like to do a part two, three and four, because this is just one way of looking. And of course it’s not chronological, because there was no reason for it to be chronological. I didn’t write these things with the idea that they should be trapped into a certain time period by the use of language. Phew! So in the creation of this, NYC Man, it’s like a new album, as far as I’m concerned. We were very much concerned with the sequencing, and the flow. That’s it.

How did the friction between you and John Cale after White Light/White Heat come about?

I would never tell you. That’s a secret.

It’s worth a shot though.

You can try. You could always ask John. He’d just give me the same treatment, I’m sure. Probably, I don’t know.

Do you consider that Moe Tucker’s metronomic drum style was intrinsic to the Velvets’ sound?

I think Maureen Tucker is a genius drummer, and it is astonishing that people have not noticed. She started a whole new way of drumming, a different way of drumming, a style of drumming which, later, some of these ideas were incorporated whether they heard her or not. For instance, with electronic drums you remove the tyranny of the high hat. Every one of these drummers comes with a trap kit, he’s been taught to drum and he’ll play a hi-hat straight through your song. You say to him: “We don’t need a high-hat every single note here, don’t play it all the time.” Well, they can’t, because when they’re trained they’re just doing that. [Drums on table.]

You must have recognised the power of such compositions as Sweet Jane and Rock And Roll, so was the fact that they were remixed without your knowledge for 1970’s Loaded the final straw that led you to quit the Velvets?

They didn’t remix it, they just finished the mix without me. I left.

Was that the final straw?

No. The final straw was long before that.

Would you care to elucidate on this final straw?

No, it was just a terrible thing with the manager. Where the manager feels that he is more important than the artist, or is in competition with the artist. It’s always a bad situation. You know, the manager has an apartment and the artist is sleeping on the floor by the fireplace like a sheepdog.

Willie Nelson’s autobiography is very, very funny, because at the end of the book he’s staying in some really nice hotel suite wherever the hell he is. But he’s travelling with his Samoan back doctor. The Samoan doctor gets the bed, Willie – because he’s got a bad back – is sleeping on the floor. And Willie says something like: “This is kind of a parable for the music industry.” Very, very funny.

Around that time, with Moe Tucker retreating into domesticity, Sterling Morrison returning to academia and the Velvets soldiering on with Doug Yule and ultimately Willie Alexander usurping your role, did you ever consider leaving the music business altogether?

No. No. It was still fun, as long as it was fun… You know, Sterling was always threatening to go back, but Maureen just got pregnant. That’s the only thing about Loaded, she was pregnant. Our drummer was not a lesbian. Old Moe, she’s got five kids now, for God’s sake. And [her son] Richard is a guitar player. I gave him one of my custom guitars.

I talked to her two days ago and she didn’t tell me any of that. She told me one of her sons was a cook.

You talked to Moe? She’s also a brilliant songwriter. Spam Again? She’s one of the great people. She’s one of the greatest drummers. Her style of drumming, that she invented, is amazing, and you still see occasional groups where the guy will be playing standing up. But I’m surprised that the other girl drummers were very obsessed with being like a guy drummer, not with following Maureen’s lead, which is standing up, because it adds some strength. But anyway, Spam Again, any of those songs of hers. Now she’s with some group… The Kapucknicks or whatever the hell it is.

How did the deal with RCA come about, and what drew you to the UK to record your first solo album in 1971?

A friend of mine got me out of Atlantic Records by giving them a cassette that was recorded at Max’s Kansas City, which was released as a mono record called The Velvet Underground Live At Max’s. And then they got me signed to RCA as a solo artist. And then at that time the records in the UK just had a better sound to them. Better engineers, better studios, you know, for non-R&B stuff. So that was the reason to come over here.

What was your first impression of David Bowie, and in retrospect are you pleased with what he and Mick Ronson did with your second solo album, Transformer?

How can I remember my first impression of David Bowie? That’s really… [smiles] Okay… I mean, David and I are friends to this day. He’s very smart and very, very talented, and I met him in New York and thought, ‘This guy would be a fun guy to work with; we could really bring something to the dance.’

And Mick Ronson’s arrangements?

Mick Ronson’s arrangements were killer. The thing about Ronno was that I could never understand a word that he said; it’s, like, he’s from Hull. You had to ask him eight times to say something, and he was like, ‘Ouzibuzziwoozy…’ Absolutely incomprehensible… I mean, sweet guy, but incomprehensible. Completely. But listen to that arrangement of Perfect Day. That’s Ronson. But David is no slouch. We were rehearsing for our little show, and we’re doing Satellite Of Love and we were doing the real background part at the end, and the guys were really admiring David and going, “Holy shit, what a part that is.” He outdid himself.

Did it amuse you that Walk On the Wild Side sailed past the oblivious censors, right into the upper echelons of the UK singles chart?

I’m not amused by the situation at all, but that anyone would… You know, in books you have Naked Lunch and Allen Ginsberg. In movies you have God-knows-what. Who could possibly be bothered by the lyrics to Wild Side? It’s inconceivable. I mean, it is just so offensive that it’s not amusing.

Has the song become something of a millstone?

No, because without it, who knows, maybe I’d be digging a ditch somewhere. So thank God for it.

Berlin is an incredibly evocative and imaginative work, with not a Perfect Day in sight. Had you been working on the concept since the first album [where the original song Berlin appeared], and where did all of that darkness come from?

I have no idea. It was just getting together with [Bob] Ezrin, we wanted to do what we were calling a movie for the mind and it grew out of that idea. But when you say there is no Perfect Day on there, don’t be too sure about that… Melodically, there certainly is, arrangement-wise, there certainly is. The key to Perfect Day is the last line: ‘You made me forget myself / I thought I was someone else / Someone good,’ and, ‘You’re gonna reap what you sow.’ So going from there to Berlin is not a big leap. Actually, you could put that right in there without a problem, probably after Oh Jim.

It is a dark record, but it’s almost like the sum of darkness squared.

Well, it’s not, ‘Let’s sit up and dance and be happy.’ I prefer to think of it as a Bergman movie or a Kurosawa movie. You know it’s not, ‘Hey, hey, hey, yippy-doo,’ it’s more film noir. Which I guess lets Kurosawa out. But when I say Kurosawa I mean intensity, or in Rashomon, depending on how you look at it. That’s the reference points for me, if you know what I’m talking about.

It is a great album…

Boy meets girl, boy gets girl, boy loses girl and then it stops.

‘Girl slashes wrists’ isn’t normally something you’d expect to find in the equation though.

Well of course it’s not what you normally expect, but that’s the point.

But it is just that bitter pill that makes Sad Song so deliciously sad.

With that big choir… I mean, you have so many records that go the other way, and here is a chance to move you emotionally, physically – remember what I was saying – physically move you, and emotionally move you. You know, you’re not expecting it. So it’s an open shot. He’s all alone at the three-point line, ladies and gentleman, will he sink this? No one’s near him. You know.

Why did you specifically choose Berlin as the setting for Caroline and Jim’s story?

It was simply that Berlin was a divided city, and it was cosmopolitan and a very sophisticated city. It was the home of German film noir and expressionism. And I wanted this to be the city in which this little plot takes place, and it was emblematic that it was a divided city.

- Cuttin' Heads - Blind Lemon versus Lou Reed

- Lou Reed slates Beatles, Doors in lost interview

- Lou Reed & Metallica: Lulu

- Brian Eno on Roxy Music, The Velvet Underground and David Bowie

For teenagers seduced into Lou’s world by Transformer and working backwards through the Velvets’ albums, especially White Light/ White Heat, Metal Machine Music’s cover image and liner notes were utterly irresistible. You looked exactly as the originator of ‘heavy metal rock’ should have looked, and the teasing “No instruments? No” line in the album’s combative sleeve notes tapped into a nascent punk nihilism that came to define a generation. So was Metal Machine Music originally intended as conclusion or catalyst?

I was somebody who really liked heavy metal, as it was called back then, electric guitars blowing up amplifiers, and the sound of broken speakers, and I thought it would be a lot of fun not to have to worry about a drum, and not have anything for anybody to sing so you didn’t have to worry about a key. Someone working their way backwards would probably end up with the bootleg of Metal Machine Music that was very right-channel heavy, not very accurate. I doubt they would have been able to find vinyl, but there was a CD out that was not very accurate.

La Monte Young’s Dream Music is cited on the album’s cover as a progenitor of the direction you were going with Metal Machine Music, but where did you first find inspiration to stretch beyond the constraints of the ‘song’? There are echoes of Ornette Coleman’s The Shape Of Jazz To Come in the respect that critical bafflement was followed by enduring influence.

The first thing I was listening to was Ornette Coleman. Ornette Coleman. Ornette Coleman. Ornette Coleman. And then the idea of drones in back of it. But it’s Ornette, it’s always been Ornette. Lonely Woman is one of the greatest songs ever written. Not a day goes by without me coming back to it. It’s an amazing album, but that track…

What did you make of the live reinterpretation of Metal Machine Music?

Well, it was Walter Krieger who did the transcription and Rheinhold Friedl [the musical director of Berlin’s 11-piece Zeitkratzer ensemble who produced a 2002 live version of Metal Machine Music] that got in touch with me saying they wanted to do this, and I said it’s impossible. I mean, I’ve been working on doing a sequel for it forever, and it turned into Fire Music from The Raven, and I couldn’t imagine anyone possibly being able to play it live. But then they sent me an example of it and it was fantastic. They had the melodies and the harmonics, everything in it. I was astonished by it. So I said okay, and it was performed in Berlin at the Opera Halle and I performed in the third part of it. I suddenly come in on guitar, and they disappear and this one mondo guitar replaces all 10 of them, and then they come in and we all play together. And then we went to Venice with it. And then they toured around Europe doing pieces of the whole thing.

Songs like Coney Island Baby and Perfect Day are incredible hymns to the glory of love. Would you describe yourself as a great romantic?

I would not describe myself. I could not describe myself.

But then there’s the other side of the coin; do you bear any resemblance to the central characters of either Kicks or The Blue Mask?

It’s a complete and total personality. I mean, I like acting. I took acting and directing and film when I was in school, and I liked writing monologues for myself, and different parts to play. And I would bet that that’s got something to do with the variety going on in there. If I wanted to do a cowboy song, I would write myself a cowboy part. If I wanted to do a Tennessee Williams monologue, there is no one there to stop me, I’m going to try to do that.

There is great drama in what you do. For example, Street Hassle is an incredibly dramatic and evocative piece. You’re right there in the heart of the action, witnessing everything that the narrator describes.

Oh yeah, and it’s a great monologue, but there’s two monologues going on really. There’s the person in part one, the person in part two, and these two couldn’t be more polar opposite. The person acting out the first part is one way, and the complete opposite person is on the other side in part two. They’re not even vaguely of the same species.

The second character is such an absolute reptile…

[Lou laughs] And the ‘universal truth’ line is so utterly cold it’s completely fabulous. Based on a real incident, as my things inevitably are.

How did Arista Records react to Live: Take No Prisoners, possibly the most aggressive, uncooperative and angry performance ever captured on tape?

Clive Davis [Head of Arista] was always very supportive of me. When I first played him the Street Hassle album, first it’s I Wanna Be Black, and then into Street Hassle you hear: ‘That cunt’s not breathing.’ I said: “Clive?” And he said: “You are what you are. I knew that when I got you.” And with Take No Prisoners it was more of the same. I wasn’t a surprise to Clive. He didn’t go: “He did what?” He knew what I was. That’s why he signed me. He didn’t object to that. He knew what he was getting, he knew I did things like that. Clive’s smart.

And then came The Bells. Now there’s a drama.

There is a drama. That was constructed in the studio and sung one time and one time only. I’m making those lyrics up on the spot. And it’s an amazing lyric. Whatever it is. I’ve looked back at that lyric, trying to understand it, since it’s coming from a different place than usual. Unfettered by anything, it’s just going free, and there it was: ‘And the actresses relate to the actor who comes home late.’ Wow, this is my kind of… It’s like The Sweet Smell Of Success and This Is My Kind Of Town. That’s my kind of lyric. You just don’t know where it’s going to go.

Have you performed it live since the album’s accompanying tour?

No.

I saw you do it in ’79, and I seem to remember you dropping to your knees at the climax. Now that was dramatic.

Well, as long as I didn’t have them run out with a cape and do the James Brown thing. But why not?

Along with creative writing you studied journalism at Syracuse.

For a week.

It is not wholly beyond the realms of possibility that you could have become a critic yourself. Could you live with such a horrifying prospect?

No. It’s interesting. I was learning the triangular paragraph, and that was it for me. You’re not supposed to have an opinion of the triangular paragraph. So I moved from the triangular paragraph of journalism to the theory of triangular staging in drama – in the sidelines, there is always a triangle going. That’s it. So it was easy. What was difficult for me was interviewing Hubert Selby and President Havel. First I was just worried: “Is the battery going to die on me, right in the middle of everything? Should I have a back-up machine just in case?”

Welcome to my world.

It’s just too nerve-racking. My God… As if I don’t have enough to worry about.