Is there anybody out there?

Yes. Hundreds of people, actually, milling around outside the Atlantico Pavilion in Lisbon. They’re here for the second European date of the biggest and most expensively staged tour of the year: Roger Waters’ revival of The Wall, more than three decades after its original staging.

Tonight’s show is a sell-out, like most of the 50-plus dates on this leg. By the time tour finishes, around a million people will have watched an 11-metre high, 70-metre wide wall being built between them and the man they’ve come to see. The band on stage will continue to play a 32-year old album behind that wall until the end of the show, when the whole edifice will come tumbling down. A similar number of people have a already seen the show in North America last autumn. Now, as then, no one is likely to complain about not being able to see the band during the show.

The Wall is a legend in the annals of live rock music, partly because it was such a alien concept and partly because Pink Floyd, the band led by Waters at that time, performed the show just 29 times, in four cities – LA, New York, London and Dusseldorf – in 1980 and 1981. It would be the last time Waters and Pink Floyd played together until they reunited for Live 8 in 2005.

Pink Floyd never showed any interest in performing The Wall after Waters departed and guitarist David Gilmour took the helm. Waters embarked on a solo career, although he was tempted into staging a grandiose Wall in 1990 in Berlin with an all-star cast to celebrate the fall of another even more famous wall.

His career stalled soon afterwards, although it was revived at the turn of the millennium with the In The Flesh world tour and has prospered since. But there was no indication that he was planning to revisit The Wall. As he says: “It was incredibly difficult to stage back in 1980 and we lost a lot of money doing it.”

Then in April last year Waters announced that he was taking The Wall on a world tour.

“Well, I did a tour a couple of years back where I did the whole of Dark Side Of The Moon,” he explains now. “I had been reluctant to take that piece and re-do it. But it worked well. So when I’d recovered from that I thought maybe I had one more in me. My fiancé said that maybe I should do The Wall. I said I couldn’t. But it wouldn’t go away…”

Mark Fisher is mildly exasperated. As the stage designer for both the original The Wall tour and this 21st-century update, he’s heard all the talk of this new show being the sort of thing they could only dream about 30 years ago.

“It’s the same bloody wall,” he says with a sigh. “Identical. It’s frustrating that people think we’re doing something that we could not have done in 1980. The engineering behind the building of the wall – the platforms that the men go up and down on to build the wall, the stabilising masts that go up inside the wall to stop it falling over, and the cardboard bricks themselves – are exactly what I designed back in 1980. The only things that are different are connected with how they are controlled. [In 1980] I sat behind the stage with a bank of switches and moved things up and down. Now we have a computer that does the same thing and a man that watches the computer.”

As a young architecture student, the original The Wall production was Fisher’s first major design for a rock show. It was the springboard for a career as a self-styled ‘event architect’ that has seen him become the in-house stage designer on globetrotting stadium tours by The Rolling Stones and U2, as well as the opening and closing ceremonies at the Beijing Olympics.

So when Waters started thinking of bringing back The Wall, Fisher was his first call. “He told me that it would be much easier to do now than then,” says Waters. “Technology had come a long way, and people spend a lot more money on tickets than they used to. He thought I could make the figures work, and maybe even come out of it with some gravy. So I thought, okay, let’s do it.”

Inside the empty arena the actual wall is still an imposing site – even part-built and unlit – jutting out from the upper tiers of each side and tapering down to the stage. It’s not just the height, it’s also the width: three-quarters the length of a football pitch. Behind and beneath the wall is a scaffolding warren jammed with motors, hydraulic pumps, lifts, platforms and passageways. Each piece has a diagram stuck on to show exactly where it fits. And then there are the piles of ‘bricks’ that arrived flat-packed and are assembled and waiting to be laid. (They tried making them out of plastic, but plastic cracks. So it was back to cardboard and white paint.)

The projectors have been focused, the band have sound-checked. Now there’s just an echoing, quiet calm. Everything that needed to be checked has been checked. At what used to be known as the sound desk and is now the production control centre, a couple of guys are tapping on keyboards while rows of screens flicker on standby…

The calm is broken when the venue’s doors open and groups of people run to the front of the stage and take up prime position. Unlike the American shows, the European shows are freestanding on the arena floor wherever possible. This means there’s no room for the dishevelled tramp who would wander up and down the aisles at American concerts, pushing a supermarket trolley and brandishing a placard saying ‘No thought control’, before being ushered out by a burly security guy just before the show began.

In the centre of the floor a skeleton staff are minding the control centre. Banks of screens flicker on standby, waiting to be activated. The stage is similarly quiet; there are no roadies making last-minute equipment checks or tapping microphones. Everything that needed to be checked was done earlier. The only untoward item is a tailor’s dummy placed centre stage. The PA is playing a succession of Bob Dylan songs. This is the calm before the choreographed multi-media barrage is unleashed.

The Wall famously started with a gob. During the last show of Pink Floyd’s Animals tour at Montreal’s Olympic Stadium, Waters spat at a fan who was yelling drunkenly for the band to play Careful With That Axe Eugene. Afterwards Waters was so appalled by his behaviour that he sketched out the idea of a show with the band playing behind a wall to express his own feeling of alienation from the audience. He reminded the audience of the incident when the Wall tour reached Montreal’s Bell Centre last October.

“When I wrote it, it was mainly about me, a little bit about Syd Barrett, but by and large it’s about fear,” he says. “It’s about a frightened person. Fear makes you defensive, and when you’re defensive you start building defences and that could be seen as a wall.”

It has always been assumed that the original production of The Wall, which included a crashing Stuka dive bomber and giant inflatable puppets to reinforce Waters’s bleak tale of alienation, paranoia, power and war was too complex to be toured. This is another thing that irks Mark Fisher.

“The only thing that stopped it being toured in 1980 was the cost,” he says. “And it wasn’t that the show was that expensive, it was that tickets were cheap. The top price ticket at Earls Court was £8. At the O2 in May people are paying £65 to £85. That completely changes the economics of putting a touring show together.”

Fisher maintains that the ticket price reflects what the show is worth. “It allows you to spend a lot more on the hardware and the crew. We’ve spent the best part of $15 million [£9.4 million] putting this show on the road. Back in 1980 we spent about $2 million at most.”

Tour director Andrew Zweck is another veteran of the original Wall shows. He confirms that this is the biggest show Waters has put together. “There are 24 trucks parked outside,” he says backstage, with the air of someone who has spent decades keeping a close eye on the bigger picture. “There are 116 people on the road, which is more than double what we’ve had before. And that includes 14 carpenters who are just brick builders. The economics of it mean that we can now move the show overnight. The crew will be out of here by about three in the morning, and they’ll start work again around six or seven.”

While the wall itself has barely changed, other elements of the show have been greatly enhanced. The biggest advance has come with the projection. In 1980, three 35mm projectors struggled to beam Gerald Scarfe’s inimitable animations onto the wall in focus and without too much overlap. Now there are 15 HD-quality projectors pointed at the wall, with a bit-mapping grid that means that as soon as a brick is positioned on the wall it immediately becomes part of the projection. It’s a far cry from some of the early-80s shows that Mark Fisher remembers as “a mad race between the drug-crazed road crew and the band to see who could get to the intermission first”.

As Video Content Director, Sean Evans is in charge of projections. A youthful-looking, heavily tattooed American, he grew up listening to The Wall (“I know it inside-out”). Evans, Waters and editor Andy Jennison spent weeks working on ideas for the projections in an editing room.

“It was like being back at art college,” says Evans. “Right from the start Roger said: ‘I don’t want to do this as it was. I have no interest in not making this political. We have to modernise it and we have to bring a message.’”

Waters says the new show has developed from the story of one frightened man hiding behind the wall, to a more expansive look at the way nations and ideologies are divided from each other. “We are controlled by the powers that be who tell us we need to guard against the evil ones who are over there and different from us and who we must be frightened of,” he explains.

Part of the message included broadening the original album’s references to encompass other wars and acts of violence since then.

“Roger put a notice on his website asking for people to send in pictures and details of family members, civilian or military, killed in wars or terrorist acts,” says Evans. “We worked on it for months, and the first time I saw it with an audience even I welled up. During the intermission we put them all up on the wall. One night I saw a guy who’d obviously just seen a friend or relative on the wall, and he was just standing there sobbing.”

The wider message of The Wall is clear from the outset when, instead of a ‘surrogate’ Pink Floyd taking the stage and fooling the audience (the opening gambit of the original show), the PA booms out the dialogue from Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus where the Romans try to coerce the slaves into revealing the rebel leader, only to be met by a growing chorus of “I am Spartacus”.

That’s the cue for the heavy opening chords of In The Flesh? as Waters walks on and dons the long leather coat that has materialised on the tailor’s dummy. The song culminates in a bombast of old technology – lights, smoke, fireworks, and the dive-bombing plane crashing in flames – that softens you up for the barrage of images to come.

Gerald Scarfe’s remade inflatable puppets make their mark. The sylph-like wife now has a ghastly green allure (and a startling pudenda for those who are startled by that kind of thing), while the mother now cuts more of a beady, surveillance character as she scans the audience, which is reinforced by an equally inquisitive CCTV on the circular screen. Only the teacher has failed to move with the times. He may have a new jacket but he’s decidedly old-fashioned – it’s been a long time since canes were routinely swished in the classroom.

Getting Scarfe’s original animations to hold up against the new animations was another time-consuming task for Sean Evans and his team. “His stuff is legendary, you can’t mess with it. Fortunately Roger had the original film, so we were able to restore it from the best possible source, but it still took a lot of work to make it look good against the other stuff we were doing. Some of it, like the flower sequence, was actually made for the circular screen, so we extended the stems across the wall so it looked as if the flowers were coming from somewhere.”

Some of Scarfe’s other animations, such as the marching hammers, have been re-animated to fill the entire wall with a vivid brightness that borders on intimidating. Others, including the stems of the flowers, have been rendered in 3D. The projectors also make the whole edifice sway and buckle alarmingly. There are moments when you wonder if the animated trickery will upstage the climax of the show, when the wall comes crashing down.

“We’ve paced the effects so it all builds up to that point,” says Evans. “We thought about whether to add any effects to the wall as it falls. But actually it looks pretty spectacular from wherever you are in the arena, with all the smoke billowing out and stuff. But if you’re in the first five rows it feels like it’s gonna hit you. I’ve been in the pit a couple of times with a camera and gotten brained a couple of times. Those things are heavier than they look.”

Which is why, in these days of ludicrous litigation over the mildest inconvenience, a Health & Safety officer has been added to the tour payroll.

But what about the music? Waters’s current band includes guitarists Snowy White, Dave Kilminster and GE Smith, drummer Graham Broad, keyboard player John Carin and, on piano and Hammond organ, Waters’s son Harry.

Snowy White first played with Pink Floyd on their Animals tour in 1977, and he was part of the ‘surrogate’ band for the 1980 Wall shows. He has been a member of Waters’s band since 1999. And he’s happy to shed the non-committal omerta that hangs over most professional session musicians.

“This show is choreographed down to the second, because it wouldn’t work otherwise,” he explains. “The original was pretty tied down, too. People ask me if it’s boring playing exactly the same thing every night. And I thought it would be, but really it’s not. There’s a lotto think about while you’re on stage, and you’re trying to get it that little bit sweeter every night.”

- The 10 Roger Waters Tracks Every Pink Floyd Fan Should Own

- The story behind Pink Floyd’s The Wall album cover

- The Making of Pink Floyd The Wall – the movie

- Waters: Why The Wall still matters

It was White who found Dave Kilminster, who takes on the ‘poisoned chalice’ of replicating David Gilmour’s epic guitar solo on Comfortably Numb. “Roger wants it just the way it is on record, and that’s a young man’s job,” White says. “I’m happy to let Dave get up on top of the wall.”

A large proportion of the Lisbon audience is surprisingly young (“They’ve been introduced to The Wall by their parents, who may in turn have been introduced to it by their parents,” says White). It’s something that makes the team behind it proud, although ultimately job satisfaction is almost as important as the cheque. Mark Fisher took particular pleasure in watching the US leg of The Wall running neck-and-neck with Lady Gaga in terms of revenue. “Roger is unambiguously about alienation, discrimination, anti-war. The audiences have been picking up on that. You’d be hard put to know what the fuck Lady Gaga is about.”

In fact Waters’s tour would eventually outstrip Gaga’s in terms of the money it made. “We were second only to Bon Jovi, who were playing stadiums,” says Andrew Zwick. “We were offered stadiums but Roger turned them down, even though it meant we needed to play another 16 dates in America to meet the business plan. That was fine by me, too.”

Another recurring theme among the technical and creative crews is Waters’s continual attention to detail. Changes are still being made at the start of the European tour. Costumes have been altered, and the furniture in the hotel room that appears out of the wall in the second half of the show has been changed.

“That’s Roger’s trademark,” says Zweck. “He’s never satisfied. He wants to be involved in everything, every note, every image, the choreography. His fingerprints are all over The Wall.”

They were all over the original show, and the album, for that matter. It’s not as if Waters needed to reclaim The Wall, but the recognition after so long in the shadow of the band he quit must be gratifying. Mark Fisher can still remember the ignominy of Waters’s Radio KAOS tour playing to less than 500 people at Wembley Arena in 1987, and the following year Pink Floyd packed out the stadium next door.

While the original The Wall album will always be associated with Pink Floyd, it’s Waters who is clearly identified with the extraordinary success of the Wall tour. Significantly, he reasserts his authority over Comfortably Numb and Run Like Hell, the two songs with which Pink Floyd climaxed their sets in the 80s and 90s. Indeed David Gilmour’s appearance on top of the wall during Comfortably Numb was for many the high point of the original Wall production. But Waters sings the lyrics with real passion and despair and, as the guitar solo comes in, smashes his hand against the wall, which shatters, sending a collective gasp through the audience. It’s yet another gobsmacking moment.

And Waters turns the largely instrumental Run Like Hell into a dictator’s rally with waving flags, strutting feet and crossed-fist salutes. By the end of the song it’s difficult to believe that Waters didn’t orchestrate the Libyan uprising as a publicity stunt for the tour.

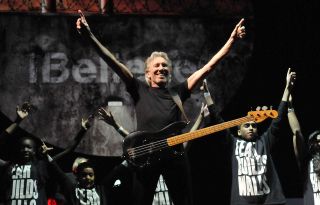

Almost as startling is Waters’s crowd-friendly demeanour, smiling, even making eye contact with fans down the front whenever he removes the long leather coat that he wears for his dictator’s role in the show. It’s a far cry from the remote, uncommunicative figure he cut for so long, not least in the original Wall shows.

“I’m completely different, and feel completely different about being on stage now than I did then,” he admits. “In the last 30 years I’ve come round to embracing the possibilities of that connection with the audience. Now I milk it mercilessly, just because it’s fun and it feels good. Whereas back then I was so fearful that when I was on stage I was the same as I was at a party – standing in a corner, not looking at anybody, smoking cigarettes and more or less saying: ‘Don’t come anywhere near me.’ Thank goodness I’ve grown up a bit since then. I like being on stage and enjoy the feeling of warmth – what’s not to like?”

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 158.