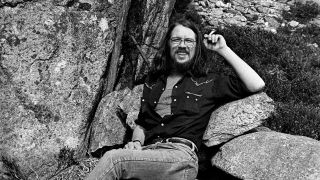

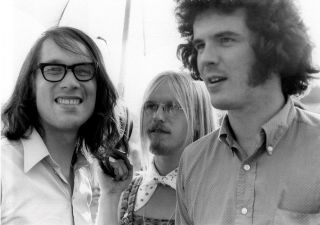

Of all the managers so far in our series, Peter Jenner is arguably the one who laid the very foundation stone of prog itself. Working with his then partner, Andrew King, the first group he managed was Pink Floyd, representing them from the summer of 1966 and, chiming with the first wave of psychedelia, getting them signed to an EMI looking to embrace the cool, the fab and the groovy.

Although placing their eggs into the Syd Barrett (bike?) basket when the group left their troubled leader, Jenner and King didn’t stand still. They put on the first free festival in Hyde Park in 1968, one of the fundamental cornerstones in building today’s burgeoning UK outdoor show culture. After leaving prog behind, Jenner looked after Ian Dury, The Clash and, for many years, Billy Bragg.

Born in 1943, Jenner had already enjoyed a packed life before he got into management. Brought up in a political family, his grandfather, Edward Wise, had been a Labour MP, and his father a socially conscious clergyman. As a teenager in the 50s, Jenner took part in CND marches. By the age of 21, he had left Cambridge with a first in Economics and taken up a position as a lecturer at the London School Of Economics. But as the 60s progressed, he sensed there was something in the air.

“We were the first generation of young people who hadn’t been in the army; who hadn’t been in the war. We were the first generation who didn’t want to be like our parents. There was a discovery of new music: Tamla, Atlantic, blues, music coming in from America that previously hadn’t been available. Then there was The Beatles and the Stones: English people writing their own songs and having huge hits and becoming international stars. They had long hair. It was clear that they smoked dope.”

It was only a matter of time before Jenner would wholeheartedly join in. “The whole alternative scene through the London Free School took off,” he says. “The underground hit the zeitgeist – it was the 60s and Harold Wilson and 20 years after the end of the war.”

Through his friend John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins, Jenner went to investigate Pink Floyd. “Floyd were the house band of the underground: if you were interested in this new underground thing, you were interested in the Floyd. I first saw them in June 1966. I went to see what it was all about because I was marking exams at the LSE and I was tired and I wanted a break.”

Jenner and Hopkins initially wanted to run a label, DNA. It was going to be progressive in outlook – they had got some funds from Elektra via mutual friend Joe Boyd, and they began producing avant-garde improvisers AMM. Soon, they realised it would be impossible to make the label a success without a pop band to buoy it up.

“I knew nothing about the business but I could see that groups like The Beatles were selling in large quantities all around the world,” Jenner says. “I asked the Floyd if they would like to be on our label. They told me they didn’t want that – what they really needed was a manager. I’d been an economist, so the idea of actually seeing how business worked was always very interesting to me.”

Jenner went to see an old childhood friend, Andrew King, to ask him to co-manage. “He’d had a small inheritance from an aunt who died, so we had some money,” Jenner says. “I didn’t know what managers did except provide money, and I think that was all the band knew that managers did. They needed some equipment so we bought them some equipment, put it in a van and it got stolen that night. Welcome to the music business! We got some more equipment on HP, and that’s how we started: because we weren’t traditional businessmen, we decided to be a partnership.”

A mark of how different Blackhill Enterprises would be was that a six-way split (between the two managers and the four members of Pink Floyd) was established, which was extremely unusual in those days.

“By Christmas, Melody Maker had given us a centre spread, saying that this was what was going to be happening next year,” says Jenner. “Queen magazine did a feature, there was something about them in the Financial Times. Somehow or another, we had hit the middle-class, post-young grad audience and their younger brothers and sisters.

“The Floyd were besieged by people wanting to sign them: for publishing, for agency, for record deals. We ended up with Bryan Morrison as our agent, who’d been a social secretary at the Central School of Art. He and fellow agent Tony Howard started working them into the universities.

“We wanted a record deal. We’d made a record: Bryan helped finance us making Arnold Layne on our own with Joe Boyd, which was a Syd song. It was interesting we chose to do that – I had sussed everyone was writing their own material, as opposed to doing a cover.”

Although a variety of offers were on the table for Pink Floyd, “EMI made us an offer we couldn’t refuse. £5,000 and recording costs, and working in Abbey Road with The Beatles’ engineer as producer.”

Arnold Layne, delivered to EMI as a fait accompli, would be their first single, and it reached No.20 in the charts. Within a handful of months, thanks to See Emily Play, Pink Floyd were a Top 10 act and there was a great deal of work for the young management team to be getting on with.

“Andrew and I worked together in an unstructured way,” Jenner recalls. “If he started doing it, he’d go on doing it, and vice versa. I probably spent a bit more time in the studio as I lived close to Abbey Road. I was a more enthusiastic smoker so I got on very well with Syd. I was also at the LSE, which was close to where Syd was living in Earlham Street, so I could pop in. The Bryan Morrison Agency was in Charing Cross Road so I could go in there. But we both did things.”

The Floyd were now a big band. “Everything fell together – anything was possible.”

That was, of course, until Barrett began to lose his sense of reality. “Syd never recovered from their American tour. And this is pure rumour and speculation, but many say it was where he got spiked. Acid was around in England: it was very serious – it was more like a religious experience rather than, ‘Let’s go down the park and have some acid.’ Syd’s last Floyd songs seemed very together. That’s what I mean about the acid in Britain, because you could still hear what the mind was doing. Later on, the confusion was so deep it was hard to know.”

The three songs in question, Vegetable Man, Scream Thy Last Scream and Jugband Blues, have long been the very essence of the Barrett Myth. “I’ve always thought those three songs were defining Syd’s mental collapse in some way – but they were still articulate, they still worked. Later on it didn’t work any more – somehow the songs didn’t emerge. There would be snatches, but back then there still was a song. He wrote Vegetable Man at my house. It was a description of what he was at the time. I’ve always thought that they were very important songs. If you wanted to understand Syd, you had to hear them.”

- The Managers That Built Prog: Andy Farrow

- The Managers That Built Prog: Gail Colson - the woman behind Peter Gabriel

- The Managers That Built Prog: Dave Margereson, the man behind Supertramp

- The Managers That Built Prog: Charisma's Tony Stratton-Smith

In early 1968, the Floyd, now with new member David Gilmour, left Barrett and Blackhill behind, allying with Bryan Morrison, before ending up with manager Steve O’Rourke. A young Marc Bolan had come to Blackhill because of Syd Barrett, and fortunately for Jenner, other performers came by.

“Because we looked after Floyd, we were happening people and acts came through the door. Roy Harper came to us because his manager Mike Allen wanted a record deal with EMI. We also had the Edgar Broughton Band.”

By the summer of 1968, Jenner added another string to his bow: free concerts in Hyde Park. “The concerts were my initial idea. We’d read about free concerts in Golden Gate Park, but it was a very long way away and people didn’t just pop in a plane in those days. My wife [and business partner Sumi, whom Jenner married in 1966, but who sadly passed away in 2005] and I would walk through Hyde Park. I thought the bandstand would make a great place for concerts, as they always had police and military bands.

“I wrote to Jennie Lee, Minister Of State for the Arts, and asked about doing a concert there; I also mentioned that she had once been out with my grandfather. She never wrote back, but soon, someone phoned up from the Department of Public Works to talk about the concert.”

In July 1968, the first concerts began. “They started down by the bridge across the Serpentine, in the cockpit,” Jenner says. “There was a semi-circular natural amphitheatre with natural sight lines, road access, they provided us with this foot-high stage. It was extraordinarily successful straight away.”

This series of shows over the next handful of years would feature the Rolling Stones, Pink Floyd, Blind Faith and, making their name in a single performance, King Crimson. Blackhill had a roster of acts that could feed the concerts, through the acts Jenner managed and produced: Kevin Ayers, Third Ear Band, the Edgar Broughton Band.

With an impressive roster of acts, were there any that got away? “We’d done a concert with Tyrannosaurus Rex, Roy Harper, Stefan Grossman at the Royal Festival Hall [June 3, 1968]. The opening act was this chap called David Bowie. He did a mime – it was absolutely ghastly, as he had to tell us what the mime was doing. Bowie later asked if I would manage him: I turned him down because of the embarrassment with that show.

“I’ve never really regretted it – he wouldn’t have been as successful if I’d have done him. I was much too old world public school to cope with all that androgynous fashion stuff. I was always interested in music, not fashion.”

Jenner does have one regret from back then, however. “The Edgar Broughton Band were enormously successful initially, and I was very fond of them. The band were prototype punk. They would have been huge five years later with a haircut. I became obsessed with them being in time and in tune and somehow we should have just been more animalistic. They were lovely people, did well in Germany, and somehow we never got through. I misdirected them and somehow we didn’t get out what was there.”

After Blackhill folded in the 80s, Jenner set up Sincere Management with Sumi, and presided over the careers of artists such as Eddi Reader and Billy Bragg. Is there a formula for Jenner’s success? He laughs.

“The secret to my failure is I’m not a very good businessman, the secret to my success is I’m not a very good businessman. I’m a music fan – I’ve worked with people with music I liked. Why did we start managing Ian Dury? Andrew and I went down and saw him play at the Hope And Anchor and he did England’s Glory, which blew us away.

“Look for an artist who isn’t like somebody else, and then work on that individuality. Whether it was Michael Franti, The Clash, Ian Dury, the Floyd, Syd or Eddi Reader, they’re all unique. You might or might not like them, but they are what they are.”

Peter Jenner remains a music fan and is rightly proud of what he has achieved across a 50-year career. He’s a passionate voice today in the UK music industry and a champion for artist copyright. And his advice for young managers?

“You have got to know the business. Study a bit of history and understand about what the rights are. What is publishing? What is a record deal? What’s the price of that advance, that loan? A lifetime of getting it wrong teaches you those models. Do it – that’s my advice. Do it with someone who blows you away and doesn’t sound like anyone else. Try to be humble and always ask people for advice. I still do.”

With the final Syd Barrett recording becoming officially available this festive season, Pink Floyd never really leave Jenner. He recently attended David Gilmour’s shows at the Albert Hall, and he noted the songs that “people really love are the ones about Syd. It’s extraordinary how they all – but particularly Roger and Nick, as architects by training – built this whole thing on the foundations of Syd’s work. And not just Syd but what Andrew and I and Hoppy did, the people who came in with the lights and the first promotion we sent out where we talked about a multimedia psychedelic experience.

“The lights were part of the show. The lights, sound and improvisation, a lot of that came from the Syd era and they built on it.”

JENNER’S GEMS

Six sublime shows

1. Pink Floyd (Games For May) Queen Elizabeth Hall, London, May 12, 1967.

2. Billy Bragg (Jobs For A Change GLC Festival) Jubilee Gardens, London, June 10, 1984.

3. The Clash Palladium, New York, September 21, 1979

4. Ian Dury and the Blockheads Do It Yourself UK tour, 1979. “They were incredible gigs!”

5. Eddi Reader singing the Songs Of Robert Burns Glasgow, 2009.

6. Edgar Broughton Band “Some time ago. We’d driven 36 hours to Aarhus in Denmark to play. There were fewer punters than staff. They played this extraordinary gig. It was improvised; real stream of consciousness. It went from song into improvisation – it was by far their best gig and they could never recapture it.”

JENNER’S TREASURES

Five fabulous recordings

1. The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn Pink Floyd, Columbia, 1967.

2. New Boots And Panties!! Ian Dury, Stiff, 1977.

3. London Calling The Clash, CBS, 1979.

4. Stormcock Roy Harper, Harvest, 1971.

5. Hypocrisy Is The Greatest Luxury The Disposable Heroes Of Hiphoprisy, 4th & Broadway, 1992.