Born in Shannon, County Clare in 1973, John Mitchell was adopted and raised in the idyllic village of Hambleden, Berkshire. As a boy, he’d run around a nearby wood with his mates playing guns, and for a while he was plagued by recurring nightmares. One would inspire the cover for The Big Dream, his terrific second outing as Lonely Robot.

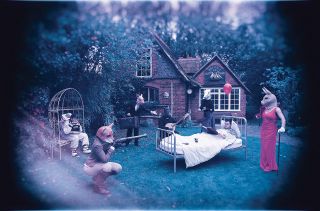

“I’d be running through this wood,” he tells Prog, “and I’d be set upon by these terrifying people with animals’ heads. Some people have seen the cover and asked if it’s a homage to Genesis’ Foxtrot, but I don’t really listen to Genesis, so I didn’t make that association. It’s about that dream.”

Three decades on he found himself hauling a wrought iron hospital bed up a long, tall hill to a glade in that very same wood, to be photographed in his pyjamas as friends loomed over him in jodhpurs, clerical collars, space suits and bestial masks. Passing ramblers were freaked out.

John Mitchell has had some happier if equally surreal moments of late. In March he met his all-time guitar hero, Trevor Rabin, at ARW’s show in Birmingham. “It was an absolute high point in my life. We had a long chat in the hotel bar and put the world to rights. They say don’t meet your heroes, but I got lucky there – he’s a gentleman.” He also recently received his first royalty statement for Lonely Robot’s debut album, 2015’s Please Come Home, and it made his jaw drop. “It’s the first time I’ve earned mechanical royalties from a record. I felt like cracking the champagne! Normally you get the advance and that’s it, but it sold a remarkable amount. I’m so pleased.”

This success is a validation for one of prog’s journeymen. In 2004 he formed his first proper band, the short-lived Kino, with It Bites’ John Beck and Bob Dalton, Marillion’s Pete Trewavas and ex-Porcupine Tree drummer Chris Maitland. He has sealed his reputation as a highly gifted guitarist – for Clive Nolan’s Arena and Jem Godfrey’s wonderful outfit Frost* – and also as a frontman, fearlessly assuming Francis Dunnery’s place for It Bites’ all-too-brief renaissance.

His commitments to these bands work in series rather than in parallel. Most of the time he’s holed up at Outhouse Studios, his recording facility set in a beautifully appointed, 300-year-old Victorian coaching inn, where he produces records for the likes of Enter Shikari, Architects and You Me At Six. As we speak he’s furiously trying to finish up Kim Seviour’s debut solo album. It’s also Mission Control for Lonely Robot.

It was InsideOut label head Thomas Waber who convinced him to produce his solo work under a band name, the wisdom being that band albums sell better than artists’ eponymous ones. Waber also suggested it would be worth hitting his Rolodex for a few guest appearances on the debut record. Steve Hogarth, Heather Findlay, Nik Kershaw and others duly obliged. “Of course it’s handy from a marketing perspective,” says Mitchell now, “but if you’re a Marillion fan and Steve plays a bit of piano on my album, there’s no evidence you’ll then listen to it. I got him in for the right reasons – he’s a great pianist, and a very good friend of mine. It’s not like I rang someone from, I dunno, Slayer to do a solo to appeal to Slayer’s fans! I’m extremely proud of what everyone brought to the table for Please Come Home.”

The Big Dream was all but completed last October and set for release in winter, but Mitchell contracted a nasty bronchial tract infection and was unable to sing for three months, missing his window. “Then I went through a period of asking myself if the album was just a load of old rubbish, if I should abandon it. I do have low self-esteem at the best of times, so I go through these periods of wondering if what I’ve put together is any good.”

Having recuperated, he returned to the album and realised it was anything but rubbish, and finished it with renewed vigour. Lonely Robot’s second release is Mitchell’s most distilled, personal album to date, and his most compelling. Second time round, the only guests are Frost* drummer Craig Blundell and ex-Creatures Of Love singer Bonita McKinney, whose strong backing vocals complement Mitchell’s husky tones, notably on Hello World Goodbye. But the first voice you hear on The Big Dream belongs to a man who died the year Mitchell was born.

Author of books including 1957’s The Way To Zen, hippie philosopher Alan Watts played a major part in introducing Buddhist thought to the West, and the album’s interspersed with archive audio of Watts discussing the nature of existence and consciousness, and chiming with Mitchell’s own themes. “Alan had a very calming voice,” says the guitarist. “So in between getting battered with 7⁄8 you’ve got that to look forward to. He was a great advocate of this idea of ‘the solipsistic haze’ – that are we all a part of somebody else’s imagining, that life is a great conspiracy, a grand design, a dream. On the last album I explored the disconnect between humans and the Earth, that perhaps we weren’t originally from this planet. This time I thought it’d be fun to get into the idea of that solipsistic haze. Listening to Watts’ lectures, a lot of his philosophies point towards it, and I found great comfort in that.”

Musically, The Big Dream is less a departure from Please Come Home than a confident expansion of it. When he’s not writing or producing, Mitchell only really listens to movie soundtracks, be it Hans Zimmer’s for Interstellar, Clint Mansell’s for Moon, or Alan Silvestri’s for Contact. This Jodie Foster film keeps cropping up in our conversation: when bemoaning the modern-day reliance on social media, he quotes Matthew McConaughey’s character, who reckons we’ve become a ‘synthesised society’. (“That resonates more than ever now. People don’t truly know how to communicate with each other”.) In the film, the SETI radar array picks up an otherworldly, rhythmic radio signal sent by an alien intelligence, and that short sound effect actually appears on the album’s title track – distorted, pitch-shifted, it’s used almost as a metronome for Craig Blundell’s imperious drumming.

Indeed, much of the album’s musical texture is drawn from the sci-fi realm, from such very precise sound design details to the grand harmonic language of the songs they imbue. Prologue (Deep Sleep) comes in on subtle strings, a dual flute motif echoing through space, and electronic blips and blops. It evokes the eerie opening of Alien, when Ripley and crew are woken out of their cryogenic sleep by the Nostromo’s computer, as all hell awaits them. “That’s exactly what you’re supposed to think,” says Mitchell, pleased. “There’s a little atonal thing that’s a nod to that.”

His Astronaut character thus wakes into ‘reality’ (you can imagine Watts air-quoting the word). Awakenings has a downtuned guitar riff, a huge chorus, and one of Mitchell’s beautifully lyrical guitar solos is prefaced by a Mellotron choir. “It’s that old, dark string sound used on the Alien soundtrack,” says the man who reckons he can count the prog bands he likes on one hand. “That’s my reference, not Larks’ Tongues In Aspic!”

With its huge, infectious refrain, Sigma is an odd pop song contending that humans don’t learn from history (‘Now the writing on the wall can never bury you/All along the signs were there staring straight back at you’). Lead track Everglow has what he calls an anti-chorus: it sounds like a positive message; it’s actually invective.

“The everglow is the feeling people get when they vent on a social media platform. You say, ‘This is wrong, that’s wrong’ and all your mates online go, ‘Yeah!’ But if you’ve got a problem with somebody, fucking well tell them, don’t vindicate yourself through this keyboard warrior mentality! I’ve been guilty of it in the past myself. I know people who can really hold forth on Facebook but can’t actually answer a phone call. It’s disconcerting.”

The album’s powerful effect is cumulative. A dozen listens in you’re still spotting interesting details – a digital glitch on the heartbreaking vocal of In Floral Green; the near sub-sonic bass drop and tranquil lapping of waves that ends the Celtic, Blade Runner-referencing Epilogue (Sea Beams). “I’ve got a little sailing boat moored off Mylor, in Cornwall,” Mitchell says with a longing laugh. “The calmest I could ever be is just off the Cornwall coast with the engine off and the sails up. I’m so glad I ended the album with that sound.”

Once, as a producer, he was asked to conjure up the sound of purple falling into mercury. He does see music in colours, and for this album he sought a ‘green’ sound, one that chimed with that pastoral cover shot, and ran counter to the grey we’re surrounded by in our daily lives – the concrete. “Part of the human psyche misses the biological aspect of the colour green,” he says. “I don’t think people are aware of what they’re missing.”

With its shimmering, Muse-like synth hook, False Lights has a verse in 5⁄4 and a chorus in 6⁄8, with shifts so smooth you could almost dance to it. Symbolic comes with a whistling, X-Files-like line and one of the most nuanced, explosive guitar solos he’s ever recorded. And maybe he doesn’t listen to Genesis, but the piano-led anthem The Divine Art Of Being evokes Take Me Home and Peter Gabriel’s Red Rain too. It’s all the more stirring for it.

Then we leave the Astronaut to his cryogenic sleep; his Matrix-age, human battery-cell life. “That’s where he ends up,” says Mitchell, before quoting late comedian Bill Hicks. “‘Go back to bed, America! Your government is in control. Here’s American Gladiators. Watch this, shut up!’ The whole album’s a strange meeting of everything I’ve ever wanted to do musically. I haven’t thought of it before this moment, but if I wanted to write an album, then it should encompass my love of film soundtracks, detuned metal guitar and have proggy moments. The Big Dream is an amalgamation of literally everything I love.”

His early experience with Kino taught him that writing by committee was not for him. As he puts it: “Somebody always has to be Napoleon! Kino never ended up being quite what I wanted it to be, but there’s a line from there to here, because I wanted to have a band as a vehicle for my songwriting. Lonely Robot is me writing music, a bit more focused and more clued up than I was back then.

“I’ve come to the conclusion that I’m a hermit, and a complete, benevolent dictator. I did co-write with Jem on the last Frost* album though [2016’s brilliant Falling Satellites]. We’re like-minded, but I like to have the basic structure of a song quickly, to bash the fence up then cover it in glitter later. Jem likes to look at the details from the start. John Beck says I’m halfway between himself and Francis Dunnery. Even I’m not as impatient as Francis, whereas John’s ethos is that slow and easy always wins the race.”

But fronting his Lonely Robot band is different, there’s more of him in it, and he was uncharacteristically nervous ahead of the launch show, at Reading club Sub89. The day after he opened for Marillion at their Weekend at De Montfort Hall, and on May 27 he’ll headline the Prog-sponsored all-star charity event Trinity 2 at the Assembly in Leamington Spa.

Live, Lonely Robot band is Mitchell, Blundell, keyboardist Liam Holmes and bassist Steve Vantsis. Back when he was playing guitar in John Wetton’s band, Mitchell asked the man if he wanted the solos – such as Allan Holdsworth’s on UK’s In The Dead Of Night – played exactly as on the record. “John said, ‘No, I didn’t get you in the band to copy other people. I want you to do your own thing.’ I never forgot that. I don’t expect the band to copy my parts, I want them to embellish them.”

A complete, benevolent dictator then. But not a total control freak.

This article originally appeared in issue 77 of Prog Magazine.