Everyone who was there at the time can remember exactly where they were when they first heard Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. For Rick Wakeman, the epiphany came in the living room of his parents’ suburban house in Northolt Park Green, Middlesex as he listened to his father’s old Radiogram.

“The BBC were doing the first playing of it, and I was eagerly awaiting this album, just as everybody was,” recalls Wakeman of hearing The Beatles’ landmark eighth album. “The opening blew me away. I thought, ‘This is just something else.’ And then what came on after it was just, ‘Oh wow, this is completely different.’ The next day I bought it. As did millions and millions of others.”

Roger Waters – whose own band, Pink Floyd, recorded their debut album The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn in Abbey Road at the same time as The Beatles were laying down Sgt Pepper – was listening to the same broadcast as he was driving to some long-forgotten destination.

“I remember pulling the car over into a lay‑by, and we sat there and listened to it,” Waters told US radio station KLCS a few years ago. “Somebody played the whole thing on the radio. And I can remember sitting in this old, beat-up Zephyr 4, like that [sits for a long period, completely agape].”

For Steve Hackett, his first encounter with the record that would come to define the era and help sow the seeds for progressive rock came slightly later. “I grew up in Pimlico, so Chelsea was on the doorstep,” says the guitarist today. “I remember going to the Chelsea antiques market. I went up to the second floor, into this room that had Indian hanging silks, and there was this strange music playing. It wasn’t until I got hold of the album that I realised it was Within You Without You. They had completely reinvented themselves, unrecognisably so in fact.”

Sgt Pepper has just turned 50, and the fact that so many people have such clear memories half a century on is testament to its standing as one of the most significant albums ever released. As with so many other strands of music, its influence on prog is huge.

Let’s be clear: Sgt Pepper wasn’t the first progressive rock album. But the record, as with the band who created it, did more than any other to open up the minds of a generation of aspiring musicians who would go on to lay down the foundations of progressive rock soon afterwards.

“The Beatles were the first progressive band,” says Jon Anderson, who was a year from co-founding Yes when Sgt Pepper was released in May 1967. “There were other bands making adventurous music – The Beach Boys, Frank Zappa and various others. But The Beatles were doing it first, not just with Sgt Pepper, but before too.”

Anderson himself was playing residencies in Hamburg with his band The Warriors when he first heard Sgt Pepper. “Me and my friends in the band played that album endlessly for about three weeks,” he says. “We’d do a show, then go back and listen to Sgt Pepper all night. We were high as kites, on so many levels, then the album came out and we got even higher. It was like someone opening a door to revolutionary music.”

Sgt Pepper didn’t come entirely out of the blue. The Beatles had long since transcended their roots as an R&B-influenced pop band, something proven by the 1966 single Eleanor Rigby, a slice of foreboding Scouse Gothic that sounded like nothing that had come before.

“Eleanor Rigby was such a groundbreaking song,” says Hackett. “It wasn’t a traditional pop song. It was this character portrait, this short story. And you can almost smell the dust on the old instruments that were being used. It had such an adventurous spirit, and you can trace that thread into Sgt Pepper.”

That song, along with the equally revolutionary psychedelic freakout Tomorrow Never Knows, appear on 1966’s Revolver, the last album the band recorded before they announced their retirement from touring in August of that year. That decision proved to be arguably the most significant of their career, allowing them to devote their attention to the studio – something that, in the hands of The Beatles and their producer George Martin, became the most important instrument in their arsenal.

The sobriquet of ‘The Fifth Beatle’ has frequently been hung around Martin’s neck, and rightly so. He began as their producer, arranger and mentor, but by the time of Sgt Pepper, he was their co-conspirator too. It was Martin who did everything from manipulating the tape loops on Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds, playing the harpsichord on Fixing A Hole and pioneering the use of cross‑fades to remove the gaps between songs to creating the famous 40-second long final chord on A Day In The Life. Remarkably, all of this was done on four-track machines.

“When George told me the limited equipment they had to record it on, and the way he bounced one track onto another to make sure they had enough to do the next thing, I just thought, ‘How the hell did they do it?’” says Wakeman. “This was a man and a band trying very hard to record music that technically shouldn’t have been possible. It was that spirit of studio experimentation that the progressive bands would pick up on.”

The Beatles recorded Sgt Pepper with Martin and engineer Geoff Emerick over a period of five months between November 1966 and April 1967. It was a measure of how fast the creative river was flowing that the first song they recorded for Sgt Pepper, Lennon’s kaleidoscopic Strawberry Fields Forever, was hived off as a stand-alone double A-side single backed by Penny Lane in February 1967 and didn’t feature on the finished album (memorably, Strawberry Fields Forever was one of the first hit singles to feature a Mellotron, which Lennon had been introduced to by The Moody Blues’ Mike Pinder).

The seed for the (very) loose Sgt Pepper concept came from Paul McCartney, who had the idea of a set of songs recorded by a fictional band who were one part Edwardian music hall entertainers, one part LSD-fuelled visionaries. It wasn’t a concept album as such – and even if it was, it was a long way from being the first – but as with virtually everything they did, The Beatles popularised the idea that a set of songs could be conceptually and musically linked.

“Sgt Pepper was undoubtedly a form of concept prog,” says Rick Wakeman. “It might not have been a full-on concept album, but there’s seriously conceptual stuff in there.”

“It’s a film for the ear,” says Steve Hackett. “There are all these little character portraits, vignettes. The Beatles were really good at coming up with these flashpoints in people’s lives. Like She’s Leaving Home – the moment where she’s just about to go. Or Being For The Benefit Of Mr Kite!, where it wanders into the fairground at the end. That’s so vivid.”

But strip away both the quasi-conceptual element and George Martin’s groundbreaking production, and Sgt Pepper works on the most elemental level. Like the prog bands they inspired, The Beatles realised that all the highfalutin artistry was nothing without a great song at the heart of it.

- TeamRock Radio is back. But after what happened, why have we kept the name?

- The Prog Magazine Radio Show Is Back!

- Every song on The Beatles' Sgt. Pepper ranked from worst to best

- The Beatles Quiz: how well do you know Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band?

“Musically, their songwriting was at the highest quality,” says Wakeman. “If you’ve got a great song, you can do anything with it. That showed with A Little Help From My Friends. Joe Cocker turned this pretty little pop tune into a classic rock song.”

Even the album’s most overtly progressive moment, the climactic A Day In The Life, is effectively two relatively conventional songs spliced together. Jon Anderson has even covered it live, unaccompanied apart from a ukelele. “It’s a beautiful song,” he says. “Very progressive, but also very simple.”

When Sgt Pepper was released on June 1, 1967, the revolution was already underway.In America, the psychedelic underground was emerging, arms outstretched, into the sunlight. In Britain, the youthquakes of the mid-60s had helped set London swinging. Sgt Pepper was simultaneously the bridge between these two worlds and their soundtrack.

“You have to remember that this was more than just music,” says Steve Hackett. “We got stoned to it, made love to it, all of those things. It’s part of your DNA if you were that age at the time. It’s more than just a record. It defines the times.”

Part of the album’s attraction for some was its countercultural connections, especially its associations with drug culture, most notably on Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds. John Lennon and Paul McCartney both denied the song was a not-so-sly nod to LSD, while the latter insisted that the album wasn’t written under the influence of any kind of drug. But for many of the people listening, the end result had much the same effect.

“Sgt Pepper was very cosmic,” says Anderson. “We got pretty stoned listening to it without drugs. It was just a constant flow of emotion.”

Pepper had a more earthly impact too. The 45rpm single had long been the pop industry’s format of choice (and major cash cow), but its importance was being eroded. Inspired in part by folk-era Bob Dylan, The Beatles had shown that the long-playing album could be more than just a collection of hits with 1966’s Revolver, cracking open the door for Zappa, The Beach Boys and countless others. But such was the cultural weight of the one-time Fab Four that Sgt Pepper enshrined the notion of the album as a self-contained piece of art, one of the pillars of progressive rock.

“Sgt Pepper established the fact that albums were the new big thing,” Pink Floyd’s Nick Mason said. “We have a huge debt of gratitude to The Beatles because it transformed the relationship with the record company, who stopped trying to make us make singles and more or less said, ‘Get on with it.’ And it gave us far more studio time and far more opportunity to work on different ideas and so on.”

The Beatles had already broadened the parameters of pop on Rubber Soul and its follow-up Revolver, but Sgt Pepper offered a full-spectrum musical experience. All life was here, from undiluted psychedelia (Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds) and proto-hard rock (the all-too-brief reprise of the title track) to the heartfelt quasi-Eastern spiritualism of George Harrison’s Within You Without You, a song that Steve Hackett marks as “a significant turning point in what would become known as world music”. But at heart, Sgt Pepper was part of the grand British music hall tradition that would extend to some of prog’s more theatrical exponents, not least Genesis.

“There’s an aspect of The Beatles that’s a vaudeville band,” says Hackett. “There’s as much George Formby in there as there was Chuck Berry. But that was their strength – they were able to draw from British music hall tradition, R&B and even Indian music. They adopted a pan-genre approach that made it possible for so many other British bands to go, ‘Right then, if they’ve done that, we can include a bit of jazz or a bit of classical…’”

Sgt Pepper’s impact on prog’s founding fathers was instantaneous. In the wake of hearing it, Jon Anderson remembers urging his band The Warriors to rehearse more “because we had all this new and wonderful music to be made. They told me to piss off, so I left and eventually met Chris Squire and formed Yes”.

For others, the possibility was more existential. “What I learned was that it was okay for us to express ourselves,” said Roger Waters. “That we could be free artists and there was value in that freedom.”

For others still, it was musical: Robert Fripp, who had listened to the same BBC broadcast as Rick Wakeman, recalled King Crimson covering Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds during the band’s early rehearsals. As The Moody Blues’ Justin Hayward says: “Whatever The Beatles did, people followed.”

The debate about whether Sgt Pepper is even a prog album – let alone the first – still rages 50 years after its release. But whatever question you raise, Pepper has an answer. Take the most common claim levelled at it: that it lacks the moments of individual virtuosity that would come to define prog. True, but what it does have is a collective virtuosity on almost every level – musical, conceptual, cultural, spiritual. Zappa, The Beach Boys and the rest each possessed several of those characteristics, but Pepper was the only one that truly brought them all together. And that, more than anything, mark it as the true starting point for prog’s 50-year-and-counting adventure.

“It moved things forward a couple of years in an instant,” says Rick Wakeman. “It took us that much closer to what would become progressive rock.”

“Pepper is the template for all things weird and wonderful,” says Steve Hackett. “The Beatles decided they were going to change everything. And thank God they did.”

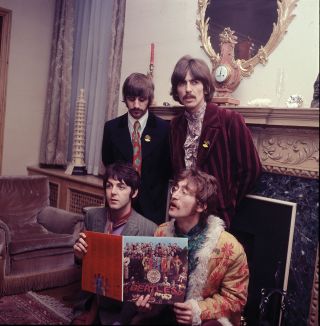

The Beatles celebrate Sgt Pepper with various special anniversary edition releases. For more information, see www.thebeatlesonline.co.uk.

Hear previously unreleased outtake from The Beatles' Sgt. Pepper