This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 169

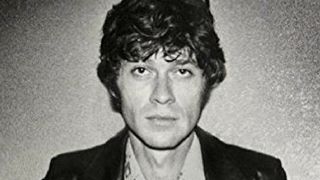

Silly me. I assumed that I would be interviewing Robbie Robertson in the quaint Kensington mews flat that I had been sent to. But instead of the bijoux bedsit I was expecting, the front door leads straight into a spacious garage. Several doors, a twisting passageway and a long walk later I’m suddenly in the elegantly appointed basement of a sumptuous townhouse in the next street. And there is Robbie Robertson on the sofa, clad in the suave black favoured by superannuated rock stars that also matches his fulsome head of jet black hair. His craggy face now reflects his Mohawk North American Indian ancestry on his mother’s side.

He’s still smiling at the memory of the previous evening’s appearance on Later With Jools. It’s the utterly eclectic nature of that show that tempts guys like Robbie Robertson out of performing retirement. He’s tickled at having played on the same bill as Femi Kuti (“His father made music that people literally lived and died for”), Cee-Lo (“I remember him from the Goodie Mob”) and Bootsy Collins (“His wife came up to me and said I was a hero to them. I’m still trying to figure that out”).

Naturally he was introduced by Jools as “The legendary Robbie Robertson” as he played a couple of songs from his new album, How To Become Clairvoyant. But you could tell from the blank expressions of the audience, most of whom were under 40, that they were unsure what proffered him that status. After all, it’s been a dozen years since his last album. And 35 years since the band that earned him his legendary status broke up.

What band? The Band. Their first two albums, 1968’s Music From Big Pink and 1969’s The Band, are among the most significant in rock’n’roll history. They defined Americana, introducing America to its cultural folk roots. When Eric Clapton first heard them he effectively lost interest in Cream. He wanted to join them but he was too nervous to ask, so he formed Blind Faith instead.

The Band also backed Bob Dylan when he went electric on his notorious 1966 world tour and recorded the pivotal Basement Tapes with him the following year in upstate New York. When they broke up in 1976 they did so with a star-studded bash in San Francisco that featured Neil Young, Eric Clapton, Muddy Waters, Van Morrison, Joni Mitchell – and of course Bob Dylan – that became one of the great rock’n’roll movies, The Last Waltz. So to many casual rock fans The Band were just a superior backing group.

Robertson acknowledges that The Band’s attitude didn’t help their cause. “The name alone was saying: ‘This is anti-show business’. Nobody in this group was going to be ripping off their shirt and singing ‘Baby, baby give it to me’. That wasn’t our calling. We were just five very individual musicians who did something very magical together. And it was only about the music. It wasn’t about trendiness, it wasn’t about selling records, it was about telling a truth. And if anybody wanted to hear that truth, it was there on the records.” “We were not looking for fame. We’d been together for seven years before we made Music From Big Pink,” he elaborates. “We were suspicious of successful music. It wasn’t a game for us. We wanted to do something really special. And there was a pureness that I still feel very proud of.”

After The Band broke up, Robertson produced the music for The Last Waltz director Martin Scorsese’s films Raging Bull, The King Of Comedy and The Colour Of Money. Their relationship has continued ever since. “I have a great collaborative thing going on with Martin,” he says. “The idea is that whatever he’s thinking I have to challenge that and raise the bar higher.”

He didn’t get around to his first solo album until 1987 – “I wasn’t sure I had something to say” – when he hooked up with producer Daniel Lanois, then basking in the success of Peter Gabriel and U2 albums. Robertson’s self-titled disc brought a fashionably atmospheric twist to his ongoing fascination with American culture.

His next album, four years later, was a carefully crafted homage to the music of New Orleans titled Storyville. He then turned his attention to his own roots, releasing Music For The Native Americans in 1994, which he wrote for a TV documentary, and Contact From The Underworld Of Redboy, which fused native American music with hip-hop in 1998.

His former Band-mates had not fared so well however. There were recriminations that Robertson had broken up the group prematurely and accusations from drummer and vocalist Levon Helm over songwriting royalties. In 1983 the other four members reformed the band without Robertson and began touring. Then in 1986 pianist Richard Manuel, a chronic alcoholic, committed suicide in a Florida hotel room.

In 1994 they were inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame, but Helm’s feud with Robertson had reached the point where he refused to attend. Five years later guitarist Rick Danko died in his sleep, aged 55. Although no drugs were found in his system, he had been a regular heroin user since 1968. This time it really was the end of The Band.

Robertson meanwhile landed a dream job in 2000 – with DreamWorks Records, the label set up four years earlier by record and film industry moguls David Geffen, Steven Spielberg and Jeffrey Katzenberg. As he tells it: “They came to me and said: ‘We’ve got a big sandbox for you to play in. We’ve got lots of movies, animation, music and acts. You can come and do whatever you want’.

“What really attracts my attention with projects is the idea of broadening my horizons. I’m addicted to that. And there’s also this idea for a record that I’ve been working on with Eric Clapton. That had started when he and I were hanging out and talking about stories, and some of these stories were leaking into song ideas. But there were no obligations or deadlines, just a ‘We should really do something together some time’.”

Robertson had some time on his hands after DreamWorks woke up to the record industry nightmare in 2005 and folded. “Eric invited to me to London a couple of years ago to work on some ideas in the studio. We didn’t know if it might be for an Eric record or a duet album or whatever, but we recorded all the tracks for the album. Later Eric said: ‘This is really going in your direction. I’ll help you in any way I can but it needs to be your record’. Now there’s a dear friend for you!

“While we’d been recording I was saying things like: ‘I imagine this song having keyboards on it’, and Eric said: ‘Well, let’s call Steve Winwood and see if he’s around’. And he was. I’ve actually known Steve for longer than I’ve known Eric, so it felt like we’d been playing together for years. It was one of the most beautiful, warm experiences that you could ever ask for.

“I’d got the basic tracks and some vocal ideas, and then Martin Scorsese rang up and said he needed help with the music for his latest movie, Shutter Island. For once he didn’t have any ideas or clues about where to start. So I read the script and suggested we should use modern composers. I put some stuff together but I wasn’t an authority, so that was another fascinating learning curve.

“When I came back to this record, somehow that experience had opened up the skies for me,” Robertson continues. “I knew what I wanted to write about, I knew how to finish what I’d started. And I knew I wanted to work with [pedal steel player] Robert Randolph. I wanted to work with [Rage Against The Machine guitarist] Tom Morello. And I wanted to work with Trent Reznor.”

All these modern musicians were known to Robertson because he’d been ridiculously well paid at DreamWorks to keep up with musical trends. “It was almost like casting a movie. I mean, Robert Randolph and Tom Morello both play guitar but I have no understanding of what they’re doing. Tom plays guitar like this (he crosses his hands over his stomach) with the plug out on the strings. I have no idea what the man’s doing. But he was perfect for this song I had called Axman because what he does is the opposite of what I do. He plays the part of this character in the song and both of us can pay homage to these great guitar slingers that are no longer with us.”

Robert Randolph was earmarked for a song called Straight Down The Line that harks back to Robertson’s musical apprenticeship backing Canadian rocker Ronnie Hawkins as one of The Hawks in the early 1960s.

“Robert plays with both feet going on pedals for wah-wah and bending the notes, and his hands are flying all over the place hitting things, and he’s got ten strings to play with. And his pedal steel does not sound like a Grand Ole Opry instrument at all. So that added another whole dimension as I’m singing about Mahalia Jackson and Sonny Boy Williamson and all those other great gospel and blues singers. At one point I venture into a line from Amazing Grace on my guitar and Robert follows me right in there. He’s like: ‘Wait a minute, I’m from that neighbourhood’.”

Trent Reznor has moved effortlessly from Nine Inch Nails into the soundtrack arena, winning a Grammy for The Social Network. “I’ve known Trent from way back and I know he’s in a cinematic place, so he was a natural choice for this traditional theme that I’d worked on with Eric called Madame X. I needed a modern counterpoint to that to make it complete and Trent did exactly what I was hoping to get. He got the whole mystery of it. It was so connected to this whole clairvoyance thing that I was into.”

What makes How To Become Clairvoyant different from any previous Robertson record are the lyrics, which are personal in a way that he has never attempted before. “I don’t know how that started,” he replies. “When I discovered that I was revisiting things and reflecting on stuff it surprised me as much as anyone.

“When I was writing songs for the guys in The Band I was always figuring out what Rick Danko would sound great at singing, what Levon Helm could sing that could tear your heart out, and what Richard Manuel could sing that would make you cry. So I couldn’t be writing songs about me. I preferred to be the storyteller, turning the truth into beautiful mythology.”

The lyrics may be personal but they are observations rather than confessions; as on This Is Where I Get Off which addresses his decision to leave The Band in 1976, thereby ending the group as a creative force. As Robertson sings, ‘Walking out of the band/Was never the plan/We just drifted off course/ Couldn’t strike up the band… This was trouble in the making/But it’s a risk worth taking’.

“The Band was great until we became really successful and then things started to separate,” he explains. “People started to become disconnected from one another. You try and try and then you realise, ‘I don’t know how to do this’. In the end you just have to accept what’s going on.” Has he talked to his two surviving Band compadres (Levon Helm and keyboard player Garth Hudson) about this? “I think that we all feel the same things in different ways,” he replies. “Losing Richard and Rick really said it all. That was why I had to get off. You don’t want to hurt people but you have to survive.”

Survival is also the theme of He Don’t Live Here No More – ‘Got a ticket on the mainline/I was stranded on the fault line/I got wasted on the moonshine/Too far gone’. “I was writing that song for Eric. He came to the studio one day straight from a meeting of his fellowship. And I was thinking that this whole recovery situation is something to talk about, without blame. Because this was some dangerous shit that we came through. And some of us got out and some of us didn’t.

“So I’m reflecting on that and on times with The Band and on some times with Martin Scorsese because he and I went through that tunnel together. We thought we were playing but we were dying. So we had to change course and get out of there. And thank God Eric was able to change course in his life, because I’d known him through all of this. And I thought it was an honest thing to write about. I don’t know if anyone wants to hear it but I couldn’t help but express it.”

One era that is not directly mentioned is Dylan’s infamous 1966 tour that drew hostile reactions from audiences unable to countenance the reality of Dylan backed by a rock’n’roll band. It’s vividly caught on the Live 1966 – The “Royal Albert Hall” Concert (actually Manchester Free Trade Hall) where the crowd’s discontent culminates in the cry of “Judas” before Dylan snarls his way through Like A Rolling Stone.

“It’s not as obvious but it’s in there, believe me,” he says. “You’ve just got to be clairvoyant to see it. It just seemed… interesting at the time. We had no understanding that we were being part of a musical revolution at the time. That whole idea of going round the world for months and people booing you and throwing stuff at you – we had no idea that it was going to build character. It was just a funny way to make a buck as far as we were concerned.

“After I’d done all these things to the record,” he says standing up, off to his next interview, “I sent it to Eric, just because we had started this whole thing together, and he rang me and said: ‘Holy shit, I don’t know where all this comes from. I don’t understand what you’ve done. But it’s fucking great’. And that was all I needed to hear.”