Jay Aston can remember when Gene Loves Jezebel started to fall apart. It was around the time of their 1987 album The House Of Dolls, and his band had changed from spider-haired post-punks into goth-pop pin-ups. “I’d been planning to leave Gene Loves Jezebel for a while and form a band with our bassist. I was getting frustrated with how things were and how my brother was.”

His identical twin Michael can remember when it unravelled, too. “That album, The House Of Dolls, was awful. I was in agony at how simple the songs had become, how moronic the lyrics were. I didn’t want to be around that. So I left.”

The story of Gene Loves Jezebel, the band who brought an explosion of vivid colour to the black-and-white palette of 1980s goth, is summed up in those two quotes. Not the literal story – that stretches back to a steel town in South Wales at the end of the 1970s and continues right up to the present day. But together they encapsulate the real story of Gene Loves Jezebel, a fraternal bond that was strained, then broken beyond repair. Today, two versions of Gene Loves Jezebel exist, one led by Jay Aston, the other by Michael, each eyeing the other with a mixture of frustration and hostility.

This was originally supposed to be an interview with Jay Aston about Dance Underwater, the new album from his version of Gene Loves Jezebel, their first in 14 years. But it soon became apparent that one brother’s story is only half the picture. “I don’t want to talk about my brother too much,” says Jay, politely. The truth is, it’s unavoidable.

The old notion that twins are halves of the same whole is a glib cliché, yet for all the distance that separates Jay and Michael Aston in 2017, they’re more alike than not. Part of it is down to simple genetics – they look the same, sound the same, sing the same way, at least to the outsider. And for all the rancour between them, their view of what happened with Gene Loves Jezebel is the same song with a different tune.

Like so many musicians who came of age in the late 70s, Gene Loves Jezebel were outsiders. As kids in the steel town of Porthcawl, South Wales, the Astons spent much of their time fighting with the local rugby boys. “You had two options,” says Jay. “You either got beat up or fought back.” The Astons fought back. “Just because someone’s skinny doesn’t mean they can’t handle themselves.”

Music provided an escape: punk and post-punk, Bowie, Zeppelin. Jay loved the epic pop of the Beach Boys and Phil Spector. For Michael it was Van Morrison and Bob Dylan. They were close, though not quite as close as you might imagine.

“That’s a great myth about twins,” says Jay. “We weren’t just hanging out with each other. We had separate friends, we were in different forms at school. He was always in steady relationships, always looking to have families and kids. I was much more of a loner.”

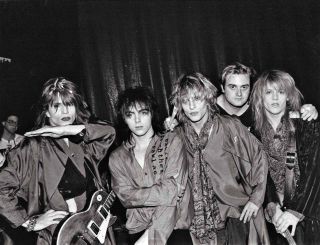

They were outsiders when they moved to London and put together Gene Loves Jezebel at the start of the 1980s too. Michael’s then wife studied at St Martin’s College, and they immediately found themselves in the midst of a febrile underground movement where music intersected with art, fashion and alternative culture. With their spidery post-punk songs and equally spidery haircuts (“tarantula tops” as Jay calls them), they slotted instantly into this demi-monde, even if the Astons never quite felt comfortable being part of it.

“We very shy and quite insecure,” says Michael. “It might have come over as arrogance. We’d see Robert Smith and Siouxise Sioux in clubs, but I never felt confident enough to walk up and say: ‘I love your music, I’ve seen you twenty-five times.’”

“We wanted to be different,” says Jay. “We were looking for our own sound, our own look. There was no word for it yet.”

That word – ‘goth’ – would come later, but their debut album, 1983’s Promise, nonetheless pinned its dark colours to the mast of this emerging scene. Songs such as the twisted, incestuous Upstairs and majestic Screaming (For Emmalene) swirled with gloomily romantic atmosphere. The twins’ near-telepathic intertwined vocals – complete with moans and birdlike cries – instantly set them apart from their contemporaries.

In early 1984, Gene Loves Jezebel flew to New York for the first time, small‑town boys in the Big Apple. They played two shows at the Danceteria, the new-wave nightclub that was the chicest hangout of the mid-80s, and recorded a session with former Velvet Underground man John Cale.

The Cale session never saw the light of day, but the Astons had got a taste of America. Where British radio stations and TV shows like The Tube largely ignored Gene Loves Jezebel, America embraced them. “Those were the days where we used to wear a lot of make-up, silks and satins,” says Jay. “And this was before we went on stage. We weren’t like Bruce Springsteen, who would just turn up in jeans and a T-shirt. People would look at us and say: ‘What, is it Halloween?’”

The Astons had graduated from cut-off T-shirts and ‘tarantula top’ haircuts to a look that was one part 80s rock star, two parts pre-Raphaelite god. Their music had changed too: Immigrant still swirled in its own dark space, but it looked outwards rather than inwards, flourishing silk scarves rather than staring at its feet.

1986’s Discover drifted further towards rock’s centre ground. The videos they made for the singles Desire (Come And Get It) and Heartache were glossy, pouting MTV fodder that repositioned the Astons as pin-ups: Michael, blond and shamanic; Jay, purple-haired and brooding. They inspired devotion from their fans, and strange rumours – innuendo suggested the brothers were lovers. The band would get followed when they walked down the street. “I felt like Peter Pan,” Jay says. “I couldn’t go anywhere without people pulling at my hair.”

But for at least one twin, something was being lost in the transformation. Original guitarist Ian Hudson suffered a nervous breakdown midway through the band’s first American tour. “We knew something was wrong when he tried to throw himself out of a window,” Michael says drily.

- The Top 10 Essential Goth Albums

- The TeamRock+ Singles Club

- TeamRock Radio app back on Apple’s app store

- Gene Loves Jezebel - Dance Underwater album review

Hudson was replaced by former Generation X guitarist James Stephenson, who – at least in Michael’s view – brought an unwelcome shot of commercialism to the band.

“I felt around Immigrant that we really were a unique band and that we really had something that was our own,” says Michael. “And I think we lost that and become a little bit more generic. Musically it wasn’t terribly demanding.”

That wasn’t the only thing that was changing within Gene Loves Jezebel. According to Michael Aston, his brother was demanding to take lead vocals on more and more songs. Jay counters by saying that Michael was becoming harder to work with. Both say the other was spending less time in the studio. Tensions were starting to boil over.

“I was always trying to leave, trying to start new things,” says Jay. “You have to find out who you are, you have to be brave in life. But I was constantly being pulled back in.”

It was Michael who eventually walked out, during sessions for their fourth album, 1987’s glossy The House Of Dolls, frustrated by the band’s increasingly commercial sound. He eventually appeared on just a handful of the album’s tracks, including the slick single Motion Of Love.

“Our first record has songs about having sex with your mother [Upstairs],” says Michael. “That was radical. We went from that to Motion Of Love

– I can’t tell you how miserable that song made me. I thought it destroyed our legacy.”

Jay: “Songs like Motion Of Love only sound overly commercial because he had to be included on them. We had to get someone on backing vocals, even though they’re not needed. He’s just as responsible for the poppiness. He’s being dishonest. He’s just trying to be cool.”

The reasons behind the initial schism between the twins were musical, but today they’re re-framed as personal. “Jay had a secondary role in the band for a long time. I think he was bitter about that,” says Michael. “He’s my twin brother and I loved him. I said: ‘Okay, you think you can do it, good luck to you.’”

“The way it worked originally was: ‘Jay, you play guitar and sing, but Mike has to sing because he’s got nothing else to do,’ says Jay. “But it came to a point where it took a long time to get things done.”

While Michael pursued his own career, first with new band Edith Grove and then with a solo album, Why Me Why This Why Now, Jay continued under the Gene Loves Jezebel banner. He made two more albums without his brother: 1990’s Kiss Of Life and 1993’s Heavenly Bodies. Both were beset by problems – the former was re-recorded at a cost of $250,000, while the latter’s chances of success were scuppered when their label, Savage, went bust soon after the album was released.

The fraternal bond hadn’t been completely severed, and, somewhat inevitably, the pair signed a management deal together. A reunion tour was followed by a brand new Gene Loves Jezebel album, VII, supposed to be the first to feature both brothers in a decade. But when it emerged in 1997, Michael was conspicuous by his absence. The old tensions had resurfaced, though the brothers have different takes on what happened.

“VII was a difficult record to make,” says Jay. “We were in a position where someone wanted my brother to be on it. They were all my songs.”

“They took a record that I’d made, put together for them and erased all my songs, all my vocals,” says Michael. “I thought: ‘I won’t let you get away with this.’”

This time it was Michael who continued to use the Gene Loves Jezebel moniker. Jay sued his brother over the rights to the name. A lengthy court battle followed that eventually resulted in Jay dropping his lawsuit. But it was too late, a line had been crossed. “I fought for the Gene Loves Jezebel name because I wanted to establish what I was in Gene Loves Jezebel,” says Michael. “In many ways I regret doing that. But I was so angry.”

The upshot was that there were suddenly two Gene Loves Jezebels. The Michael-led version was the more proactive, releasing three albums between 1999 and 2003. Jay’s, which consisted of the band’s early-90s line-up, was slower out of the blocks – 2003’s semi-acoustic The Thornfield Sessions was their sole album until this year’s Dance Underwater.

While Michael continued to gig, Jay came close to walking away from music altogether. “I was smoking two packs of Marlboro a day, drinking too much,” he says. “I’d lost interest.”

He began working for Apple in London. It was a call in 2010 from a friend who had been in an early Gene Loves Jezebel line-up, asking if Jay wanted to sing on a Rolling Stones tribute album, that revived his interest in playing music. Solo gigs and an album with former bandmate Pete Rizzo under the name Ugly Buggs followed, though it would be seven years before the Gene Loves Jezebel name reappeared on an album again. “The landscape has changed so much,” says Jay. “We funded this via Pledge. It’s a long way from half a million dollars on an album or a couple of hundred grand on a video.”

Unsurprisingly, Michael Aston’s name is nowhere near Dance Underwater. Today the brothers’ relationship sits somewhere between non‑existent and outright toxic. Jay accuses Michael of attempting to block his version of the band from playing in the US and Brazil. According to Michael, they haven’t spoken to each other since their father’s funeral almost 10 years ago. Both agree that a reunion is out of the question.

“He’s a manipulative person,“ says Jay. “He’s all out for Michael Aston; he’s not out for anyone else. If he could have done it without me, he quite happily would have. He needed my talent. And the minute he couldn’t exploit me, he’d had enough.”

“Even beyond the lawsuits, it’s the slandering, the lies, the false narratives, the cruelty,” says Michael, who has recently been working on new music with Depeche Mode producer John Fryer. “It’s been mean for no reason.”

Both brothers have made peace with the idea of there being two Gene Loves Jezebels in action, if not with each other. “If you’ve got a twin, you’ve an ally immediately,” Jay says. “It was the both of us against the world. But things happen along the way.”

Dance Underwater by Jay Aston’s Gene Loves Jezebel is out now via Westworld Recordings.