Hailed by many as the best blues harmonica player this country ever produced, Cyril Davies was a grumpy, balding panel beater who happened to lead the London R&B scene that shaped British rock, yet made few records before passing away in January 1964 at the age of only 31.

The man nicknamed ‘Squirrel’ was an aggressive purist who blew with untamed elemental power in Blues Incorporated; the world’s first white electric blues band he formed with the better-known Alexis Korner and one of the most significant outfits in the history of British rock’n’roll. Cyril helped the nascent Rolling Stones with early gigs and encouragement and inspired Ray Davies to make a go of The Kinks. Jimmy Page says he “pioneered a sound that was to give incentive to every group of the time”. But, curiously and unjustly, Cyril has been all but air-brushed out of the musical history he helped shape.

Born in 1932 in the Buckinghamshire commuter town of Denham, by the early 50s Cyril was running his own auto repair and salvage business. After playing trad jazz guitar in pubs, he opened the London Skiffle Centre upstairs at the Roundhouse pub on Wardour Street in 1955 and sang Lead Belly songs on 12-string guitar. The Roundhouse became the epicentre of London’s blues movement after Davies met the likeminded Korner and, at Cyril’s suggestion, became the London Blues and Barrelhouse Club, booking American legends Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Muddy Waters and Memphis Slim.

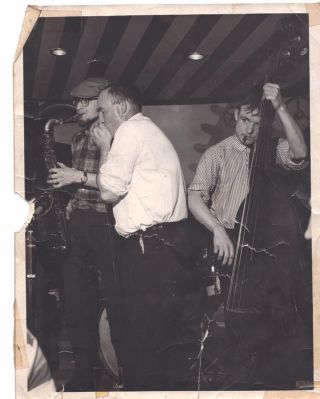

In February 1957, the renamed Alexis Korner’s Breakdown Group Featuring Cyril Davies recorded Blues From The Roundhouse, including heartfelt blues, skiffle and Cyril’s three Lead Belly covers. The band had become Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated by the time it recorded Volume Two in April 1958. That October, Muddy Waters visited the UK to play his only London club date at the Roundhouse – said to be the first time an electric guitar had been seen in a London club, and was duly heckled. Muddy’s tough electric blues proved a revelation for Cyril, who amplified his harp with a small pick-up covered with rubber from a bicycle tyre attached to a cable.

After being thrown out of the Roundhouse for being too loud, Korner and Davies opened the Ealing Club, opposite Ealing Broadway tube station, in March 1962. The leaky basement was always packed, attracting like-minded acolytes, including Mick Jagger (who’d get up to sing), Keith Richards, Rod Stewart, Jimmy Page, John Mayall, Eric Clapton, Eric Burdon and bottleneck guitar maestro Brian Jones. Even Jagger suffered Cyril’s legendary bluntness, recalling, “I learned an enormous amount from Cyril, but he wasn’t an expansive person, he was very gruff, almost to the point of rudeness.” Richards remembers “he used to drink bourbon like a fish”.

Chris Barber booked Blues Inc. to host the first ‘Rhythm & Blues Night’ at the Marquee every Thursday from May. After the residency resulted in a Decca contract, Blues Inc. recorded R&B At The Marquee, which included Muddy and Korner tunes plus Cyril’s abrasive Spooky But Nice and Keep Your Hands Off. August saw Ginger Baker replace the Stones-bound Charlie Watts in Blues Inc., joined by bassist Jack Bruce then anarchic sax hurricane Graham Bond. Disapproving of these jazzier elements, Cyril left to form his All-Stars with members of Screaming Lord Sutch’s Savages, including future Stones pianist Nicky Hopkins, and Jimmy Page before he started concentrating on session work. “I don’t like to see the music messed about with,” announced Cyril. “I like it straight.”

January 1963 saw Korner move to the Flamingo, while Cyril retained the Marquee (The Stones were given the interval slot but soon shown the door when they requested more money). Cyril’s new band also played the Roaring Twenties, Piccadilly Club and Eel Pie Island. Jimmy Page was often in the audience, recalling, “It was a fantastic band, the best blues band of the day.”

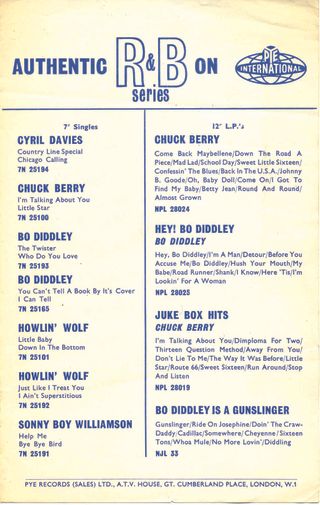

After signing to PyeRecords in February, the All Stars recorded what was effectively the first British blues single, locomotive stage fave Country Line Special and Chicago Calling, Cyril’s yearning tribute to the city he would never see. Hugely influential, Ray Davies called it “the record that kick-started The Kinks… one of the greatest records of its type ever made… I saw the band when I was at Hornsey Art School in 1962… The Kinks came through after that.”

Pete Townshend described it as “one of my hottest tracks at the time!”, and asked Hopkins to play on The Who’s first album.

August saw a second single: Cyril’s evangelical Preachin’ The Blues and Lead Belly’s Sweet Mary, promoted by tours with Gerry And The Pacemakers and Billy J Kramer.

“On pop tours I shall still play the same way,” declared Cyril. “I can’t play any other. You have to try to bend the public, not the music.” The All-Stars were guests on the Beatles’ Pop Go The Beatles radio series and appeared at the 1963 National Jazz and Blues festival in Richmond when the Rolling Stones were first band on.

By now, the hard-living blues lifestyle Cyril worshipped, including violence and villainy, had given him pleurisy. He died on January 7, 1964 from endocarditis, an inflammation of the heart’s inner layer, and never saw the world-changing impact of his pure blues mission.

Preachin’ The Blues: The Cyril Davies Memorial Album, gathers every track he appeared on in his tragically short career, showing an untamed genius just starting his tragically curtailed journey.

For more, visit cyrildavies.com

The Mississippi Saxophone

…or the harmonica, as it’s better known. We take a look at one of the sounds that shaped rock’n’roll

‘The blues had a baby and they named it rock‘n’roll,’ sang Muddy Waters. And he was right, of course. Once he and Howlin’ Wolf started plugging into amps in the clubs of Chicago in the 1950s, the blues became supercharged; a tougher, urban sound that prioritised electric guitar and lascivious lyrics.

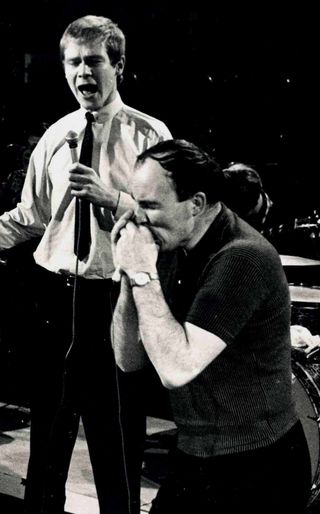

And central to Chicago blues was the harmonica. Marion ‘Little Walter’ Jacobs pioneered a new amplified approach, radically transforming it into a powerful lead instrument. Subsequently, the blues became increasingly intertwined with rock’n’roll, with The Yardbirds backing then-unknown harp player Sonny Boy Williamson on a UK tour and releasing the 1963 album Sonny Boy Williamson And The Yardbirds. Not that the notoriously surly Williamson was impressed, observing: “These young English boys wanna play the blues so bad; and they play it – so bad.”

As black music began to cross over and reach wider audiences of young, white rock fans, the harmonica was pushed further into the mainstream – nobody being more responsible for that than Paul Butterfield. The Paul Butterfield Blues Band, released in 1965, showcased the singer’s virtuosic ability on the instrument. But while clearly influenced by the Chicago masters, this was resolutely rock music. Suddenly the blues harp, as it became known, was appearing on some of the biggest hits of the time, such as wailing over The Doors’ classic Roadhouse Blues, or its mystical presence on Canned Heat’s On the Road Again?

The harmonica’s prominence peaked during the 70s, with a number of the rock musicians keen to embrace its earthy authenticity. Robert Plant does his best Sonny Boy impression on Bring It On Home and blows a raucous solo on Nobody’s Fault But Mine, though the instrument is at its most effective on When The Levee Breaks. Keith Richards maintains that Mick Jagger is one of the best exponents of the blues harp, and his playing has enriched some of the Stones’ finest moments. Midnight Rambler wouldn’t sound so sweet without a little lubrication from Mick’s harp, and his solo on Gimme Shelter makes the track sound even more menacing.

Of the many high-profile rock‘n’rollers who play the harmonica, Steven Tyler is arguably the most accomplished. From One Way Street on Aerosmith’s debut to huge hits such as Pink and Cryin’, Tyler has always pulled a tasteful bluesy line from the ‘Mississippi saxophone’.

As the decades rolled on, the instrument seemed to fall out of favour, although Spike or Mike Monroe might whip it out on occasion. It may have had its day in the sun as far as modern rock is concerned, but the sound of the humble harmonica is still blowing in the wind.