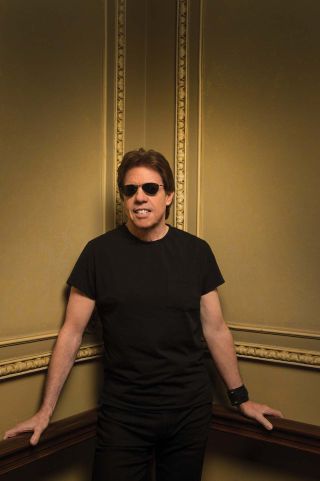

If it’s Friday, this must be the Museum of Ballooning in New Jersey, the latest turn off the road for George Thorogood And The Destroyers and their deep-rooted blues bar-band boogie. “We’re not playing near any of the balloons,” Thorogood assures us, such quirks of the schedule barely registering this far into a career that began with him nearly starving on the streets of San Francisco.

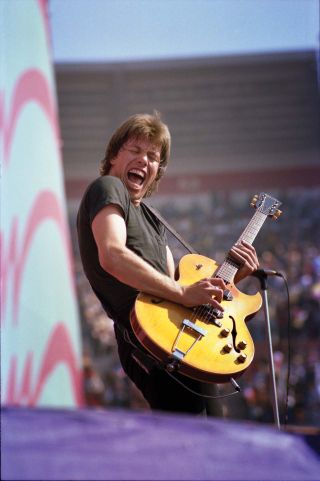

In the 80s, Thorogood and his band reached the heights of playing the US Live Aid concert, and shared bills with fans Dylan and the Stones. Thorogood’s signature song Bad To The Bone, which brought 1950s R&B into the MTV age – equally recalling Marlon Brando in The Wild One, the young, stuttering speed-freak Roger Daltrey and Howlin’ Wolf – remains a soundtrack staple, and Thorogood’s sole self-written classic. Running variations of it (Born To Be Bad), while further exploring the blues songbook with which he first made his name, secured his American stardom for the decade.

Even during his greatest fame, though, Thorogood’s blues was never in fashion. Not having Springsteen’s songwriting chops and ability to conjure new directions, he was more a throwback to the blues-honouring, covers-heavy early (and recent) Stones. His reasons for making new records petered out. “The Destroyers and I have kind of levelled off over the last few years,” Thorogood says of their professional situation.

Always true to himself, just as he has been to his wife Marla for 36 years, such reliability could look like a rut.

In 2017, though, one more turn of his trusted formula has been found – and it’s a revelation. At the age of 67, Thorogood has just released his first ever solo album, Party Of One, a one-man show that sets his strengths in sharp relief. Covering key influences from Johnny Cash to John Lee Hooker, he brings out the character of each with a fine actor’s skill and conviction.

The mostly acoustic record rolls back to his formative years when, as he told interviewers in the 70s, he was “basically an acoustic guitarist”. He has also returned to his original record label, Rounder, and most successful producer, Jim Gaines. Typically for a man whose career has mixed iron determination with meek self-deprecation, Thorogood needed to be gently cajoled to make it.

“I wanted to make an acoustic solo album some day,” he says, “and Rounder got interested a few years back. It was a little more strenuous playing without the Destroyers. It’s so damn hard physically. I’d get halfway through a song and my hands would be tired, because I wasn’t accustomed to doing this any more. I’d start off way too fast, or too heavy, or too hard, and then I’d stop. About halfway through I thought: ‘I’m going to ditch this project, it’s too hard, and I can’t come up with enough songs.’ Rounder and Jim were very supportive. ‘We know you can do this. There’s no rush.’”

Those struggles aren’t apparent on Party Of One. In a Rolling Stone review of Thorogood’s 1977 debut George Thorogood And The Destroyers, critic Greil Marcus summed up the general opinion of Thorogood’s journeyman credentials as a guitarist thus: “To hear George Thorogood flail his slide up and down his guitar, you might have thought he was Ben Franklin – that he’d discovered not the blues, but electricity.” Now his playing is unassumingly expressive, the sound of someone who’s been doing this all his life.

If you think you have to write songs to make them personal, meanwhile, listen to Thorogood’s take on Soft Spot, written by veteran country songwriter Gary Nicholson and Allen Shamblin, and to the feeling with which he sings about the destitute. Insisting that ‘We can’t treat ’em like being broke is some kind of crime’, he ends with his own bare plea: ‘Help them.’

“I live in the United States of America, that prides itself on being maybe the richest country in the world,” he says, “and I can’t believe that there are adult people living in the streets here, thousands of them. I try to explain this to my daughter, and I have no answer. I don’t know whether it’s shelter or jobs. I’m not a politician.

“But the question keeps nagging at me. So I was thinking it’s up to us regular working-class people to help these people out, because the government’s not helping. I was all about that anyway, before I heard the song. So I said: ‘I’ve gotta do this.’ Even though I don’t play it all that good – it’s a little out of my style. But the message isn’t out of my style.”

George Thorogood was put on his path on May 20, 1965, when the Rolling Stones appeared on the US TV show Shindig!, and insisted that Howlin’ Wolf came on with them. Brian Jones told Mick Jagger to “shut up” as the Wolf growled How Many More Years, danced with improbable speed and grace, and introduced racially schismed America to the blues as a force of nature.

“Wilmington, Delaware was like living on the set of [idealised suburban sitcom] Leave It To Beaver,” Thorogood says of his north-eastern origins, still recognisable in his sometimes drawled Yankee words. “I was like: ‘I don’t fit in with these people, man,’” he says of the other inhabitants of Wilmington back then, he recalls with a laugh that “I got my ass kicked” for being among the “three or four” Stones fans in town. “It was the world of the Beach Boys versus the world of the Rolling Stones. It was John Wayne versus John Lennon. That’s how it was divided. We were saying this is groovy stuff that’s happening, and it’s big stuff. ‘Oh, the Stones’ll never last.’

Howlin’ Wolf, meanwhile, made him dig beneath the Stones, and to realise that the blues was what he wanted to play.

In his high-school yearbook, Thorogood was voted unanimously the boy least likely to succeed. It gives an idea of Wilmington’s fear and loathing for rock’n’roll misfits, and his bad need to get out.

There was some travelling along the way, including to England, before he arrived in San Francisco as a 23-year-old street musician in the winter of 1973. His sympathies on Soft Spot make even more sense when you hear how this went.

“I was hungry,” he says. “If I didn’t play, I didn’t eat. I wanted to be in a top-of-the-line nightclub opening up for Jeff Beck, not standing freezing my ass off, begging people for money! But I had no choice. It was for two and a half, three months, which doesn’t sound that long. If I didn’t have any gigs, we’d go to a coffee house and pass the hat, or play a song to get a hamburger. But most of the time I was on the street corner playing music. If the sun moved, I moved with it. It was just something I had to do, or I’d starve.”

He was sleeping “wherever anyone would put me up. Sometimes I’d just walk the streets, or get the all-night trolley car. Sometimes you just walked all night and waited till the dawn, and found a comfortable place in the park and caught a nap. It was pretty rough. I needed to go to a dentist. ‘If I don’t get some money, my teeth are going to fall out, and I’m gonna be doomed.’ That was the thing that bothered me. That was scary.

“It wasn’t like I was ignored in San Francisco,” he explains. “It just took time to circle round clubs enough so they would hire me.”

Just as his graft paid off, a tape of his set got him on a bill with Bonnie Raitt, whose manager lured him back east, where a support slot in Boston with two of his blues heroes, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, got him a club gig for a couple of years. There he supported and hung around bluesmen.

“It was the music that connected us,” he says of these men from another world to his, even “another century”, thanks to their racistly blighted lives. “When I started playing the guitar, they started listening. They all said: ‘You’ve got the right idea.’ That was the best thing I could hear. Some guys, like Sonny, even wanted to give me a couple of bucks. ‘Man, keep your money…’ So they’d buy me a sandwich instead.

“Robert Lockwood especially took kind of a shine to me. We all knew who he was and what he stood for [Lockwood had played with Robert Johnson]. And so did he. The only thing Lockwood suggested strongly was to get an electric guitar. He said: ‘That’s the way you make money. That’s the way to get it going.’”

- George Thorogood - Party Of One album review

- Legacy: George Thorogood

- The TeamRock+ Singles Club

- TeamRock Radio app back on Apple’s app store

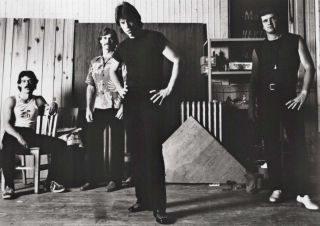

In 1973, Thorogood formed the Destroyers with school friend Jeff Simon on drums, Ron Smith on rhythm guitar (these days Jim Suhler’s job) and, from 1976, bassist Billy Blough. The then-folk label Rounder let him make a blues record, but were considerably less keen to release it. “I was w

orking on that in seventy-four, but we didn’t get it out till the end of seventy-seven,” he says. “I felt I got to the big time a couple of years late.”

When it was finally released, the songs audiences had loved at his gigs – such as One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer, and Hank Williams’s Move It On Over – did their work on vinyl, too, making George Thorogood And The Destroyers a gold-selling US hit.

Thorogood was 28 when his struggles started to pay off. “I was trying hard not to lose my mind,” he says. “I’d been waiting so long for this to happen, and the whole thing seemed to be backfiring. The record came out way past the deadline I had set for myself. A lot of the opportunities I’d looked forward to were gone. I wanted to play at the Fillmore East and Fillmore West, but they’d closed down. I’d thought it’d be cool to open for the Allmans, but Duane Allman had passed away. The things that were happening big were punk rock and disco. It was very rough going in the first couple of years. But I thought: ‘I’ve worked too hard to get to this spot. I’m going to hang in there.’”

Gigs during a week in England in 1978 were well-received by the British rock press; less so by Thorogood himself. “I was using a bad amp, a bad guitar and it was right at the peak of punk rock,” he recalls, “and a lot of people thought we were punk. I even had people spitting on me in Birmingham and Manchester, and I thought they hated me. And when I heard that Bob Dylan came to hear us at Dingwalls, I went: ‘Oh, no. Not now – you’re seeing me at my absolute worst.’”

There was one compensation. “Eric Burdon stayed in the same hotel one night. He was a gas. He really helped. He knew what it was like when you first break in. He was a good cat, and he was always one of my people. So that was groovy.”

Thorogood’s discomfort was plain in interviews back then. “Things are pretty bad when they gotta come around to me,” he told Trouser Press’s Jim Sullivan gloomily in 1981.

But that was just before the real payoff, when his determination to support his first heroes, the Stones, at last succeeded.

“I was going to walk away from the whole thing,” he says now. “The one last thing I’d like to do is get a date with the Stones, and get Mick Jagger’s autograph. Because I’ve had enough, of dealing with this industry, and the changing times that just weren’t what I thought this thing was about.

“With that attitude we played the gig, and before you know it we were working with these guys for a dozen shows. Nobody ever paid any attention until I got on that stage in front of eighty thousand people a night, and got two or three encores before the Stones, when seventy-nine thousand of them didn’t know who I was. I thought: ‘I’m on my way out anyway. Who cares? I’m going to go out there and just pretend I’m the baddest cat in the world.’ But when Bill Wyman and [the Stones’ then-keyboard player] Ian Stewart are coming out to watch you every night, and major record companies are coming after your ass, they were reinforcing what I’d told myself for years: that this is where you belong, that I wasn’t a delusional kid from Delaware. I was too old to get a big head. But these money people obviously had this vision that George Thorogood could be a rock star. Who am I to argue?”

Bad To The Bone made that official when MTV helped the track become a hit in 1982.

“It’s a tongue-in-cheek fantasy,” Thorogood says, “like Bo Diddley [who appears in the video] singing Who Do You Love? or the Stones’ Jumpin’ Jack Flash – very groovy, insecure male lyrics!”

But it was a gently downhill slope from there commercially. “You tell yourself that if the ups are high enough, then you can handle the downs,” Thorogood says. “Like an athlete in a slump, you know you’re in the big leagues, and this will pass.”

Party Of One stands out from Thorogood’s other records. He’s dubbed it a personal statement, and therefore a one-off. It’s not the sort of statement the fans in the vicinity of New Jersey’s Museum of Ballooning will be hearing later tonight.

“No,” says the hard-working, talented pro. “The promoters have hired me to do a rock’n’roll show, and that’s what we’re gonna do, to the best of our ability, with whatever energy we have at the time.”

Is he happy in his work?

“Oh, well, honey baby,” he croons, “if I’m not satisfied at this point in my life, I’d better throw it down. You dig me, brother?”

Party Of One is available now via Rounder