In September 2015, without warning, Satyr Wongraven had a seizure at home and passed out. When he came to, he was in an ambulance called by his partner, and his world was about to change in ways that he wasn’t at first able to grasp.

“In the beginning, when I was at the hospital in the first few days, I don’t think I fully realised what exactly was going on,” he recalls. “I’m not a naive optimist; I’m a little bit more wary and sceptical, and I like to double-check things. the doctors just said, ‘We’re still trying to find out what’s wrong with you, but we have discovered a cyst in your brain. It’s not cancer or anything, it’s benign, but it’s something that we just need to monitor and take it from there’.”

For an artist so fiercely driven, coming from within a black metal scene that’s always celebrated the power of will and self-determination, Satyr had entered a new, uncertain realm he’d have to learn to navigate from the ground up. “There was one part of me that thought, ‘Oh well, that didn’t sound too dramatic’. But on the other hand, I thought it couldn’t be that great because I felt terrible, ha ha ha! So I was a little confused because someone was saying, ‘Well, it sounds worse than it is and we’ll keep track of it, and if this takes a turn for the worse then we’ll have to do something more drastic’. But I was thinking, ‘Why is my pulse 32? Why am I in such a terrible shape all over and why has my body shut down completely?’”

The specialist Satyr was referred to offered some perspective, explaining that the symptoms he was suffering were fairly common for the condition, but it was the beginning of a long and ongoing road back to full health that’s called for various lifestyle adjustments, and it’s given him new perspectives in the process.

“Physically it’s kind of rough on me,” he admits, “so I had to start all over again, and I honestly feel like I’m physically not back to where I used to be because my body seems to have a harder time in terms of pushing so relentlessly as I used to. But I still work out and I’m physically active, just maybe not as kamikaze-like as before. likewise, I can party but I’m not so much of an afterparty guy anymore, ha ha ha! So for the most part you have to adjust, but we all go through so many different things in life, you have to learn to deal with it and the most important thing is to not give up on your art.”

Engaging, voluble, but a man whose steely perfectionism doesn’t lie far below the surface, Satyr is wary of relating his latest album, Deep Calleth Upon Deep, too closely to his diagnosis. In no small part that’s because the writing process had already begun a year earlier, but there’s also the fact that the four years since Satyricon’s last, self-titled album was released have offered a range of experiences that have granted him new ways of perceiving his music.

“I don’t really think of myself as ill,” he says, “because I live, basically, a normal life, but I think my perspective on a few things has become more interesting. over the last few years, I’ve done, from a musical point of view, some very interesting projects. there was the live collaboration with the royal Norwegian opera chorus at the oslo opera house in 2013, and the 20th anniversary shows for Nemesis Divina, which has put some nice perspective in the importance this band has had in a lot of people’s lives. and yes, then you can add to that a real health scare, but also in the last five years, becoming the father of two boys!”

Satyr recalls how, when his second son was born during the recording process of Deep Calleth Upon Deep, he had to be moved to an intensive care unit due to water on his lungs. Satyr sat with him until the next day, until the nurses pushed him to go home. on an impulse, he decided to head for the rehearsal studio instead. “I picked up the guitar and started playing a melody,” he remembers, “and [long-term musical partner and drummer] Frost said, ‘Wow I really like that. maybe I can play some drums around it, too.’ That ended up being the chorus of the title track. So there you go, who knows where that comes from? Maybe that’s just being awake for 30 hours, being through some sort of emotional rollercoaster, being on a high on a lot of different things and then something is building up in my subconscious as soon as I grab the guitar and start playing something. That just says something about how everything that we experience in our lives affects us, and as musicians we have our instruments as tools of expression.”

Constant agitators against the conservatism of black metal, Satyricon have always refused to look back and go over old ground. Each successive album has claimed new musical and spiritual territory, and Deep Calleth Upon Deep is another fearlessly bold step that’s likely to surprise at much as it will galvanise its listeners. Welded to its supremely efficient chassis you’ll find unexpected progressive elements, subtle classical instrumentation, saxophone parts and, emerging from its meticulously calibrated momentum, a deeply affecting new range of emotion. Be it the searching, spindly riffs peeling off To Your Brethren In The Dark’s central core or The Ghost Of Rome’s expansive surges, guided by an operatic vocal swooping above, this feels, for all its resolute, modernist temperament, like Satyricon’s most personal album to date. Deep Calleth Upon Deep may sound triumphant, but it refuses to take shortcuts, wrought instead from gristle and relentless, anvil-stamped determination.

“I like that idea of determination,” says Satyr. “I never thought about it that way, but that really says a lot about the way we feel. If people can pick up on that, that’s great. You can talk about this record and its spirituality and its darkness, but I think that what I’m hearing on this record, you say determination and I hear that, too, in all our records. But the passion is very important to me. What I hear when I listen to it, obviously I know that we feel it when we do. It has that rawness that perhaps you hear less and less of today, because in recording technology it has become important to many bands and producers for everything to sound perfect.”

Tell Satyr that the album contains much that is unexpected, but feels like it’s opened up new routes for the band to explore, and he’ll tend to agree with you. “It did end up somewhere different to what I thought it would, too,” he admits. “In the beginning there was a lot of really aggressive stuff, and there’s still a lot of really aggressive stuff, but partially because of my health scare I felt that this had to have a stronger spirituality. A lot of the time I would think, what if this is the last thing I do? And then other times I felt this is possibly the beginning of something new, so it has to be edgier than what we are doing right now. Songs couldn’t just be ‘good’; they had to feel special.”

Sixteen years since they formed, Satyricon aren’t just still going strong; their status as a relentlessly vital force, unencumbered by the drag of legacy that’s weighed so heavily on their peers, has given them a rare freedom – not just to define black metal purely on their own terms, but to drive it ever forwards, beholden to nothing but their own will. It’s an attitude that’s brought in large numbers of fans beyond the black metal cliques, and Satyr thinks he knows why.

- Watch lyric video for Satyricon’s Deep calleth upon Deep

- Last Men Standing: How Satyricon Finally Settled For Success

- Satyricon - Deep Calleth Upon Deep album review

“It’s because a lot of the same things that people outside of black metal dislike about black metal, I dislike too. I always found it to be so ironic that that group of people who would stand up for individualism at the same time want everything to be a collective. I feel that everyone is listening to the same bands, the same records and that’s boring. Let’s see if there’s something else out there that’s more interesting. I’m not a downstream guy – it’s genuinely in my nature to go upstream.”

Some have mistaken Satyr’s certitude, and his willingness to call out the failings of the scene from which he sprung, as arrogance. But for him, it’s a right that’s had to be earned. “I consider myself a black metal fan,” he states. “I consider my band a black metal band. I feel like sometimes people forget when they ask me: ‘The old-school people say…’. So you mean the other people, unlike the new-school people like me who just started doing this? I’ve been doing this my whole fucking life! I’m 41 and I started doing this when I was 15. I was 17 when I released my first black metal record. How much more old-school does it get? So when people say to me, ‘You’re breaking the rules’, I say it’s interesting that you’d say that, because I belong to a generation who made the rules, and one of the rules should be there are no rules.”

Deep Calleth Upon Deep isn’t a literal response to what Satyr has been through. It transmutes it into something more universal. It’s a gift. What advice would Satyr give to fans who have their own mountains to climb? He takes a deep breath. “Listen, I also have emotions. I also get sad and deeply upset or furious. But regardless of my emotions, what I first and foremost am driven by is: ‘OK, so this seems to be the situation, what are we going to do?’ And I think if you are able to do that, you can still be deeply sad and frustrated and upset and furious, all these things, but you will pull through it if you are prepared be a pragmatic taskmaster and become task-oriented. If you are overwhelmed with what has actually happened and you’re incapable of doing something about it yourself, rely on others too. Don’t be afraid to ask for help. It sounds simple and it is simple. That’s just the way it is!”

Deep Calleth Upon Deep is released on September 22 via Napalm.

Morbid tales

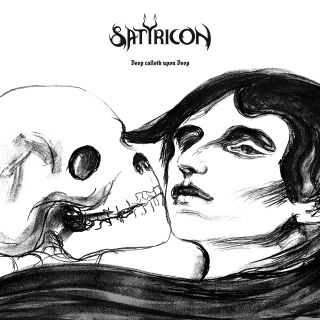

Everything you need to know about Norwegian artist Edvard Munch, whose dark drawing adorns the cover of Deep Calleth Upon Deep

Munch’s experience of mortality started early on

Born in December 1863 in Løten, Norway, Edvard Munch was the second of five children. His father, Christian, was a doctor, but was helpless when Edvard’s mother died of tuberculosis when the boy was only five years old, and his sister Johanne Sophie passed away at the age of 15 from the same disease. Johanne Sophie’s death later inspired Munch’s 1885 painting The Sick Child and many further works. Tragically, another sister, Laura Catherine, was sent to an asylum early in her life.

His morbid temperament was home-schooled

Suffering from ill health as a child, Munch was schooled at home by his pious father. That didn’t stop him from reading his son ghost stories, which inspired macabre nightmares. Edvard also said his father “was temperamentally nervous and obsessively religious – to the point of psychoneurosis. From him I inherited the seeds of madness. The angels of fear, sorrow and death stood by my side since the day I was born.”

He took an early leap from naturalism to nihilism

Having experimented with both the naturalist and impressionist styles of painting early in his career – to critical disapproval – Edvard became friends with an anarchist and a nihilist called Hans Jæger, whose celebration of artistic destruction and suicide pretty much make him an early version of Shining (Swe)’s Niklas Kvarforth. Immersed in the bohemian lifestyle, Munch sought out a more emotional, self-examining style of art.

Just like in the movie, there’s more than one Scream

There are actually four versions of Munch’s most famous painting and representation of the anxiety of modern man, The Scream. Two are painted, and permanently housed in the Oslo National Gallery; two are pastel versions, one of which was auctioned for a whopping $119,922,600 at Sotheby’s in 2012. Two of these versions have been stolen and later recovered, one of them getting damaged in the process.