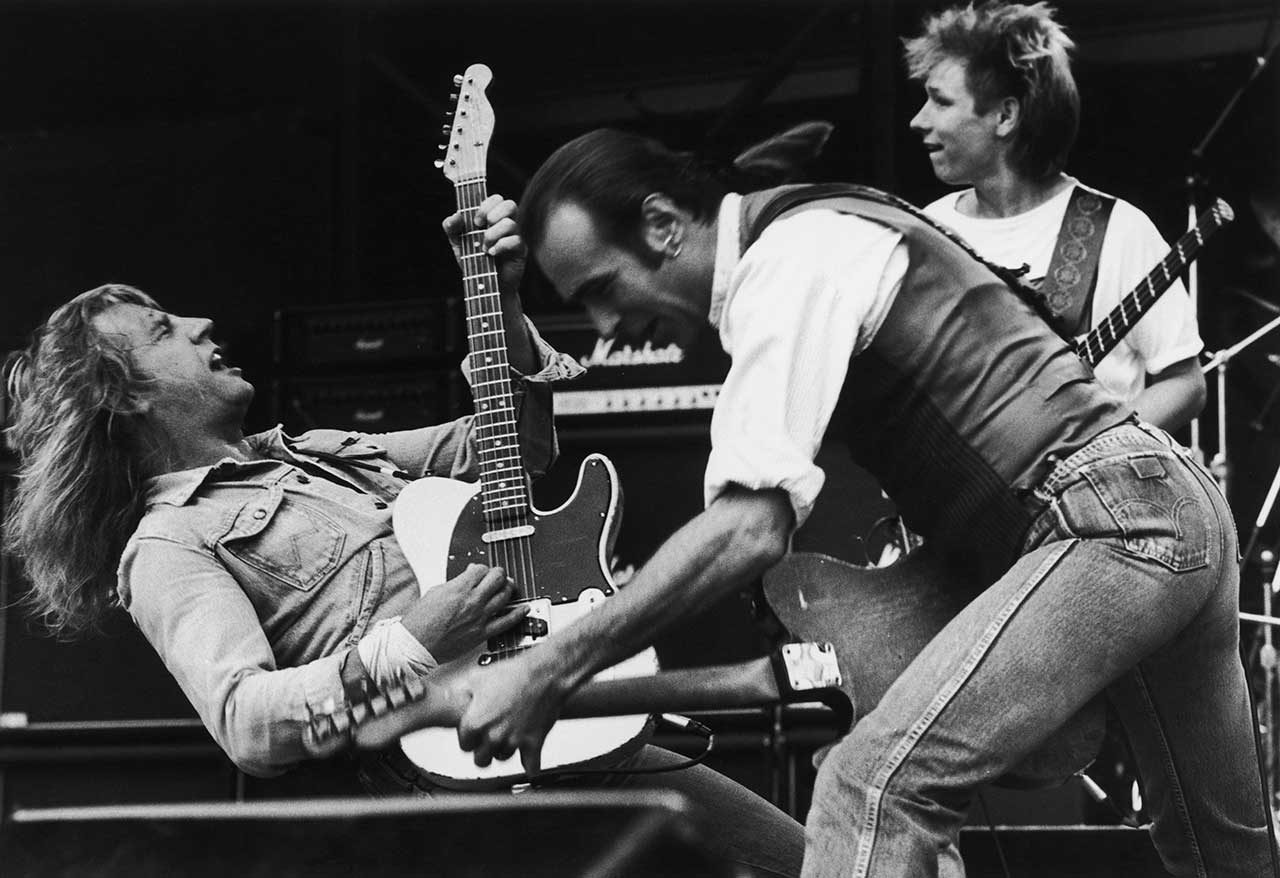

Rhino Edwards: Status Quo's bass man on his strange route through rock

Status Quo's Rhino Edwards on Rhino's Revenge, why some Quo fans want him dead, why some call him the "Frank Sinatra of rock", and why the first Frantic Four gig was a "f**king shambles"

“My nickname’s The Rhino because I like to bang and crash around,” laughs John Edwards, the bass player of Status Quo since 1986 who today is upping the profile of his own group, Rhino’s Revenge. “I don’t do too many interviews,” he divulges during the course of a hugely entertaining dialogue. Principally, one suspects, this is because journalists prefer talking to the band’s official spokespersons, Francis Rossi or the late Rick Parfitt, who died last December, though as you will learn, when it comes to tact and diplomacy, this rhino also refuses to tippy-toe around the difficult issues.

With unnecessary cheeriness Edwards volunteers: “I know that there’s a small but vocal minority of Quo fans who would rather that I stopped breathing.”

For some, this is can be attributed to the trademark short hair and effeminate looking headstock-less bass, but for others Edwards is guilty of a far more heinous crime – not being Alan Lancaster, the co-founder who was acrimoniously forced out of the group following Live Aid in 1986. And yet the bottom line is that Rhino has been a member of Quo for seven more years than the man hardcore fans call Nuff (excluding the latter’s spell with the reunited Frantic Four).

“This will look bad in print, but there’s no other way of saying it,” Edwards says of his predecessor. “I feel really sorry for Nuff that he can’t let it go. I watched a recent interview with him and he was still incredibly bitter. After more than 30 years I would hate to think that I might still harbour a grudge over something. Life’s too short.”

- Status Quo - The Last Night Of The Electrics album review

- Subscribe to Classic Rock and save up to 35% this Christmas!

- Status Quo plug back in for UK winter tour

- Status Quo - Aquostic II: That’s A Fact! album review

Rhino probably knows he’s already said too much but can’t resist a follow-up: “Look, Alan’s a lovely guy; I’ve met him a few times. He seemed great. I also like Spud [Quo’s co-founding drummer John Coghlan] which is quite bizarre as not too many people do.”

Before going further, let’s stress that the truth – or his own interpretation of it – is important to John Edwards. He’s also a determined individual who’s worked hard to reach where he is in life.

“This is all I ever wanted to do,” he smiles. “Ever since seeing Free at Richmond Athletic Ground on November 7, 1969, I was absolutely certain that I would end up in a successful group. My first band was at ten years old and I played my first gig at 11. In every band I was with, I was keener than anybody else.”

Classic Rock Newsletter

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

For the casual rock fan, Rhino’s career began with a spell in Judie Tzuke’s band during the 1980s.

“I really wouldn’t want anyone to know what I did before Judie,” he guffaws. “I backed Sandie Shaw, I backed an Elvis impersonator. I was in a band called Space who had a hit called Magic Fly [which reached Number Two in 1977]. Look it up, I was the one who resembled a cosmic ice cream salesman.”

Born in Chiswick, Edwards began in several local bands including Rococo before receiving a call suggesting he gave up the day job and headed to France for a month to play on an album by Gallic megastar Nino Ferrer. “It was a no-brainer,” Rhino recalls. Ferrer suggested the bassist should join him in a group called The Spamm Band. A self-titled offering, released in 1976, Edwards freely admits ranks among “possibly in the top ten worst albums of all time.”

Whilst in Paris he met Didier Marouani and joined Space, whose brand of electronic pop was rendered quirkier still by the wearing of ski-suits and astronaut helmets.

“It was strange. They’d call in my bedsit in Teddington the day before a gig or a TV show,” he remembers. “After collecting a first class ticket and doing what was necessary I’d be back home by that same evening.”

Later on, whilst his next band prepared to play “the hippest club in France, the Nashville Rooms”, Edwards happened upon Steve Marriott in a nearby café.

“He asked: ‘Have you got any drugs?’ I didn’t but I knew a man who did,” Rhino beams. “Steve ended up playing with us for an entire week. One time John Bonham walked in – the band that night was Simon Kirke on percussion, Boz Burrell playing tambourine, Bonham on drums, Marriott on vocals and myself on bass. That ticked a few boxes.”

Back in England, Edwards met Mike Paxman, producer of Tzuke and, eventually, Status Quo, at a party. An admirer of Edwards’ musicianship, Paxman had already had a conversation with Judie about hiring him as soon as a budget became available. Lo and behold, said party took place on the very day that such funds became available.

“It was one of many coincidences to affect my life,” he states. “Mike and I were completely drunk and he said: ‘If you can remember my number, call me tomorrow and the gig’s yours.’ At 9am, I was there: ‘Good morning’.”

For a while Edwards rotated between the bands of Tzuke and former Fleetwood Mac guitarist Peter Green, appearing on the latter’s 1980 album Little Dreamer, and also playing with the Climax Blues Band.

“Peter Green was living locally to me at the time but he was a complete and utter down ‘n’ out. He was in a bad way; it was awful,” John sighs. “Then a guy called Peter Vernon-Kell [who produced the album] stepped in and looked after him. Peter would only sing songs written by his brother Mike, which weren’t the best of tunes if I’m honest. He would occasionally stop playing and stand motionless during a take. It was so sad I thought: ‘This guy shouldn’t be here’ but at other times for 20 seconds or so he’d play a solo so incredible, I almost came in me pants.”

In 1982, following another recommendation, Edwards joined Dexy’s Midnight Runners, the self-styled young soul rebels riding high in the charts. “Literally the following day we were on a set alongside the cast of The Young Ones to film a version of Jackie Wilson Said,” he marvels. “It was the first series, nobody had seen that show before… what an anarchic experience.”

Dexy’s leader Kevin Rowland famously struggled with the pressures of fame, but Edwards didn’t exchange a crossed word with him “until he sacked me. He rang up and I mistook him for another Kevin. I was moaning about how we didn’t need to rehearse, and he replied: ‘If that’s how you feel, John, I’ll put that to the other guys in the band’. That’s when I went, ‘Oh, you’re that Kevin’!”

It was producer Pip Williams who asked Edwards and drummer Jeff Rich to play on Recorded Delivery, a solo album from Rick Parfitt that remains unreleased.

“When Quo got back together, Rick said to Francis: ‘I’ve got this rhythm section’ and it was all very seamless, though I completely understand that some people said: ‘Who’s this twat?’” chuckles Rhino. “But look, I’m a Quo fan. I saw the band in 1971 at the Winning Post in Twickenham, Thin Lizzy were supporting. It was a golden age for bands. I saw them and thought, ‘That doesn’t look too difficult’ – until I joined, and then you realise that it really is.”

Did Quo ask you to grow your hair?

“No,” he responds, spluttering with laughter. “At the beginning, Francis and Rick used to have their own spotlights and I wanted one too. I was told I could have one if grew my hair and I did try but it made me look like Worzel Gummidge.”

The following decades saw Rhino and Parfitt develop an incredibly close friendship.

“I must have spent more time with Rick than any of his wives and he was the funniest man I know – knew, sorry,” he says, correcting himself.

Asked whether he was taken aback by the full scale of the love generated by Parfitt’s death and Rhino shrugs: “Honestly, I didn’t pay much attention. I got an hour’s notice that there was something serious afoot, and afterwards I don’t recall much of Christmas. I was in shock.

When did the pair’s final conversation take place?

“Quite near the end. When he was in the UK I would go over and see him, and he seemed to be getting better. He’d realised that coming back to the band wasn’t an option because… well, he’d had a few knocks. He didn’t listen to his body and it had called out to him a few times. He’d had his collar felt in June [when Parfitt died for a few minutes following a heart attack] and he was possibly on borrowed time.”

Edwards mentions that he has just played on a number from Parfitt’s second solo album. “It’s a rocking song,” he enthuses. “There was a track that I knew Rick had wanted me to play on, so I did that. It’s a proper hardcore shuffle.”

This revelation will come as music to the ears of Quo’s hardcore faithful. The record, Over And Out will see the light of day on March 23, 2108 on earMusic.

However, those of a more casual persuasion may be unaware that Edwards actually campaigned internally for the Frantic Four to reunite for the first time in 2013.

“I felt the original four guys had unfinished business,” he explains. “They needed to go out there and do something, and then they could either put it to bed or keep on going – and put me out of a job. Of course, I went to see it, the first of the Hammersmith shows.”

And what was your verdict?

“Being brutally honest, musically it was a mess. It was fucking appalling,” he sighs. “Rick kept the whole thing going. But for sheer excitement and atmosphere it was also one of the best gigs I’ve ever attended. The guys could have got their wangers out and the place would have gone ballistic. There was a real outpouring of love. I went a second time and it was much better… but still not magical.”

Edwards has admitted that the Frantic Four’s reunion may have put him out of a job, but it didn’t happen. And yet Quo have found it impossible to put the genie back into the box. To some fans, the group ended after the Frantics signed off second time around in Dublin.

“To be honest, do I care a shit if people think that?” he retorts. “It [the reunion] ran its course, and now we’re back to the Status Quo of 2017. We still play a lot of those old songs but the Frantics really was all about nostalgia. If they had done an album I don’t think it would have been very good – not at all. Maybe Nuff will want to punch my lights out for saying that because I know he was very keen to do it, but they’re not as young as they were and the band has become something different to what it was back then, whether that’s a good or a bad thing.”

That’ll set the message boards into hyperdrive.

“Again, do I give a fuck?” he shrugs. “Those places are full of people who write: ‘I’d like to eat Alan Lancaster’s shit, Quo are the best band ever’. It’s ridiculous.”

However, Edwards fully understands why some Quo fans are irate that the band’s Last Night Of The Electrics tour, completed with a stand-in for Parfitt before he died, is no longer their last electric tour at all.

“I totally get that,” Rhino acknowledges, “but it’s hair-splitting, really. Our announcement said it was the end of electric touring. What we’re doing now is gigs [and not tours]. I understand why it might annoy people that bought tickets [for those farewell shows] but personally I’m thrilled that we’re carrying on. That doesn’t really answer your question, does it?”

Not fully, it doesn’t. So instead let us ask you point blank – should Quo really be continuing at all after the loss of Rick?

“Cor,” he winces painfully. “I know exactly what you’re saying, but… you’ll have to give me a minute to think about that. [After a few moments]: Yes, I think that we should. And that’s because when Rick wasn’t doing it last year, a lot of people still came. The one conclusion we can draw from all of this is that Francis is the only indispensable remaining member of Status Quo.”

But Rhino still can’t resist one final gag: “However, I am starting a campaign to get Francis’ son to take over from him when he retires.”

Horny Bastard: Who are Rhino’s Revenge?

You’ve described the music of Rhino’s Revenge as “a bit more of a punky bluesy style than Quo, and less subtle.”

I don’t think people understand how subtle Quo’s music is, but mine’s quite different. It’s loud and aggressive. But it’s also it’s all about the words. A lot of thought goes into those.

The likes of Cougar and Famous boast some clever and funny lyrics.

Thanks. That’s where I get off. I perform songs, as opposed to singing them. I’ve been called the Frank Sinatra of rock because I get to the note eventually but usually it takes some time. I’ve never claimed to be a great singer.

The current line-up of Rhino’s Revenge includes FM guitarist Jim Kirkpatrick and Russell Gilbrook, drummer of Uriah Heep.

When I called Russ to pick his brain over people to approach he said, ‘I’ll do it’ which was amazing because he’s my favourite drummer. We’ve got a young instrumentalist called Matthew Starritt who plays trumpet and harmonica. He’s also a better bass player than me, though I don’t like to let him know that.

Do Rhino’s Revenge perform any Quo tunes?

It’s a mix and match. We do a lot of the stuff that I wrote, and funnily enough things that I wrote with Rick Parfitt. I think it’s important to keep his legacy alive, that’s why I sang Rain [on Quo’s Last Night Of The Electrics tour]. People might think that I cheerfully murdered that song, but my whole point was that I wanted to keep it out there.

Status Quo are currently on tour. Rhino’s Revenge hit the road with King King in January, while the band’s album Rhino’s Revenge II is out now.

Dave Ling was a co-founder of Classic Rock magazine. His words have appeared in a variety of music publications, including RAW, Kerrang!, Metal Hammer, Prog, Rock Candy, Fireworks and Sounds. Dave’s life was shaped in 1974 through the purchase of a copy of Sweet’s album ‘Sweet Fanny Adams’, along with early gig experiences from Status Quo, Rush, Iron Maiden, AC/DC, Yes and Queen. As a lifelong season ticket holder of Crystal Palace FC, he is completely incapable of uttering the word ‘Br***ton’.