Under the approaching footfalls of The Who’s singer, the fashionably minimalist hardwood flooring clatters like an overworked slapstick, and my overwhelming feeling of crippling self-consciousness is almost impossible to bear.

The sheer scale of Trinifold’s Camden, North London, headquarters belongs to a different age. And on entering its hallowed, park-side portals it is almost impossible not to be impressed. Trinifold, The Who’s management company, is also that of Led Zeppelin. Consequently, hugeness is the order of the day here.

Even the most cursory glance at the interior décor at Trinifold will inundate your brain with evidence of their clients’ stratospheric achievements and enduring sonic legacy: original album artwork by John Entwistle; vintage posters for gigs by pre-Who High Numbers; prestigious awards galore; and a veritable embarrassment of precious-metal discs that recognise huge and consistent record sales figures far beyond the scope and imagination of even today’s biggest stars.

And am I intimidated? Hell, yes.

Suddenly the reverie is broken by an out-thrust hand. As I turn absent-mindedly to shake it, I’m staring into the piercing blue eyes belonging to the star of Tommy, Monterey Pop, Lisztomania, Woodstock and McVicar; the iconic Ace Face that stuttered forth the ultimate mod manifesto via the auto-destructive aggression of My Generation; the voice of Won’t Get Fooled Again, Pinball Wizard and 5.15.

“Alright, mate? I’m Rog,” the living legend smiles without ceremony. “Cup of tea?”

As the kettle fills, I suddenly feel right at home.

And herein lies Roger Daltrey’s essential magic: he really is an ordinary geezer. Just like us.

Daltrey is here ostensibly to talk about the all-singing, all-dancing DVD release of The Kids Are Alright, Jeff Stein’s 1979 film documentary that captured perfectly the rise of The Who from pill-blocked mod upstarts to all-conquering rock godheads. Now digitally buffed to a shine and restored to its original 109-minute cinema-release cut, remixed to 5.1 surround sound and expanded (it’s on two discs) by the addition of numerous mouth-watering extras, The Kids Are Alright collates early TV footage, rare Who promo clips, interview snippets, and performances from Monterey, Woodstock and Charlton FC, as well as a specially-shot intimate show at Shepperton Studios.

There’s no doubting that the finished article was the best cinematic portrait of a band ever given a cinema release, but how did it come into being? Why would a band at their peak suddenly take time out to produce what was essentially an historical document?

“A fan came to us,” Daltrey remembers, “and said he’d like to make a film using clips of the band. He did a short promo, and we said why not. We thought it was going to be some cheap little stuck-together production, and it ended up costing an arm and a leg. But Jeff did a great job. I couldn’t be objective about it at the time, but I look at it now and think it’s a really important piece of work. Jeff broke the rules. It’s complete anarchy but he gets away with it. It captures the band at the pinnacle of our career. It’s unpretentious, fun and an important rock’n’roll document. At the time it was released people were saying: ‘This film makes no sense, it’s a complete piece of rubbish.’ But now they call it one of the breakthrough moments of rock’n’roll film-making. That’s how ridiculous it is.”

The timing of The Kids Are Alright may have been totally inexplicable, but it was also quite perfect. The Who’s behind-closed-doors performance at Shepperton film studios, their first live work-out in well over a year and specifically arranged to provide contemporary footage for the movie, was also destined to be their very last show with Keith Moon.

“It was the last stand,” Daltrey shrugs. “The last gig.”

And how fortuitous that the footage ultimately captured the band in full effect, for the difference between The Who as a studio entity and as live band was always immense.

“The four walls of a studio could never contain us,” Daltrey attests. “That was the trouble. The personalities and performances were just too fucking big, and it was very difficult to do The Who justice in the studio for some reason. Even Who’s Next feels like we’re all constrained; even though they’re great performances you can still hear the constraints of the studio. But hear it played live and it’s explosive.

“We always played with the same passion. Still do today, and when that dies we’ll stop. I don’t know whether the notes are quite the same as they used to be, because I’m a lot older, but they’re good enough, and it’s never been all about just notes to me anyway. But as long as that passion remains I’ll go on doing it. It’s the passion that lives within our music on stage that makes The Who special.”

Despite the fact that The Kids Are Alright wasn’t released until after Keith Moon’s tragic death at the age of 31 in September 1978, the drummer did get to see the finished product. Just weeks prior to his drug-hastened demise, he accompanied Daltrey to a private screening. And what he saw shook him to his very core.

“He was like a blubbering baby. He was crying. He was devastated. And I kept saying to him: ‘Keith, you’re the star of the fucking film, you’re brilliant. Without you in it it would be as dull as dishwater’. And he’s saying: ‘Yeah, but I’m overweight, I can’t drum anymore’.

“It must have been like falling off the edge of a cliff for him, because he saw this beautiful young kid go from looking 16 years old to looking 40 in a very short space of time, and he found it very hard.

“I said to him: ‘Don’t worry, Keith. It’s just because we haven’t been on the road for two years. We’ll get you fit. We’ll get a gymnasium at the studio, I’ll come down with you and we’ll train, and I’ll get Pete back on the road, and you’ll soon be fit’.

“It’s because he didn’t drum. Drummers need to drum. He was devastated.”

You can see on the Shepperton footage that he was really starting to suffer behind the kit by the end of each song, I remark.

“But he’d had two years off; well, 18 months. And 18 months in the life of Keith Moon was a fucking long time, and he had overindulged in every way. He’d had California living, he’d done no exercise, hadn’t done any drumming, and he paid the price. You’ve got to think about someone with the amount of energy that he used to put into those performances – where the hell do you put it when you’re not performing? It must have been awful. It was almost like all that energy was stored up in the fat, and it had to kill him because it couldn’t come out. It’s weird.”

While many will be drawn to the charms of The Kids Are Alright for the fleet-fingered stoicism of bassist John Entwistle, the octopus-armed lunacy of Keith Moon or the windmill-delivered power chords of Pete Townshend, just as many will want to watch the chest-beating, microphone-whirling vocal machismo of Roger Daltrey – the frontman’s frontman. But not Rog.

I tell him that he seems surprisingly uncomfortable about watching himself perform, and ask if he has any interest in nostalgia. Does he doubt his own ability, I enquire, or is his singing voice simply not to his taste?

“I don’t like it,” Daltrey admits. “I never have. I know when it’s kind of right, but it’s the emotional road map that interests me. I can be objective about it 20 years later, and if I hear it coming out of somebody’s window I’ll go: ‘Fucking hell, that sounds like a good band’ and be most surprised that it’s us. But if you sat me down in front of a full-blast stereo, I’d go: ‘Well it must be alright, because it did really well’. But do I like it? Do I like my voice? No. Seeing myself is the same. It’s like everything you’re doing is clumsy, cluttery, too much, too big, and it doesn’t feel like you, it’s like somebody else. It’s very strange. My wife always says: ‘It certainly was somebody else. And I took the wrong one home’.”

You’ve said that until The Who it was always your custom to sing like Howlin’ Wolf, but on joining the band you were suddenly called upon to sing like a choirboy. Do you think that on occasion Pete writes for his own voice, thus forcing you to sing a little out of character and not to your greatest strengths?

“Now, he writes for a cross between my voice and his voice, which is fantastic. But in the early days he certainly wrote for his voice, and I had terrible trouble finding the voice for The Who. But when I first used to listen to my voice, fuck me, I’d run a mile. It always sounded like I was at the other end of a foghorn, like I’m coming down this tube at you. It had a very strange quality. But maybe because I couldn’t find the voice, it had the voice of anybody. Although it was very individual, it was the voice of everybody. Do you understand what I mean?”

Yeah, so people could relate to it more.

“Yeah. And I know it worked, because those records sold millions. But I did have trouble finding that voice. It didn’t come until Tommy. And it didn’t come from Tommy in the studio, it came from Tommy live.”

Despite an outward camaraderie and an obviously enormous mutual respect for each other as musicians, what really comes across when watching the four original members of The Who in harness is an incredible feeling of brooding antagonism. How in God’s name did they stay together for so long?

“I think we all recognised the strength in numbers. We’d all been in enough bands to recognise what it takes to be a great band. You know when the music’s good, and if the music’s good you can put up with any of the other shit. There was only once when the personalities really clashed. I don’t know whether it was all me – it certainly can’t ever be all one person – but my personality was definitely clashing with the others. And it wasn’t particularly the personalities that were clashing, it was more to do with the drugs they were taking at the time… Which were the opposite to the drugs I was taking [laughs].”

Did you ever actually come to blows?

“Oh yeah, bad blows.”

How bad?

“I had a really bad fight with Keith. That was over drugs. Because the playing had gone really, really downhill.

“We were on our first tour of Europe, and I slung the drugs away, because it was purple hearts and speed, and with the songs we were playing it just was a fucking mess. And I thought: ‘This band’s going to self-destruct’. And the band was everything to me. I was always the one who drove it. I was the guy who started out making the guitars. I drove the van, set the gear up. I was the guy who always pushed that end of it. And I could see it flying apart at the seams, and I thought: ‘Fuck it, I’m going to try and do everything I can to stop it’. And, of course, I wasn’t very articulate in those days, but I had a very useful pair of fists. But anyway, that was over drugs.

“And I had one fight with Pete where I knocked him out, which I’ve always felt bad about because it was so unnecessary. But I had no choice, because unfortunately I was the one being held back and he was hitting me with a guitar at the time.”

Well that’s not going to help matters, is it?

“No, and if you break a Gibson SG over someone’s shoulder it’ll fucking hurt [laughs]. It was only one punch, and unfortunately it hit him when he was off balance, coming forward after throwing a punch at me which I dodged. It was his own fault, because he told the roadies to let me go [laughs]. But I’ve always felt bad about it, I don’t know why. He did go out cold, and the next thing I know I’m sitting in the fucking ambulance holding his hand.”

There isn’t a great deal of offstage footage in The Kids Are Alright, but what there is gives a strong impression of how the band were. The dynamic seems to be that Pete knew exactly what strings to pull to make Keith act in the most outrageous fashion possible, while John simply sat back and shook his head, and you were left to pick up the pieces. Is that a fair summation?

“That’s about right,” Daltrey laughs. “Hole in one, mate. Pete would always be the instigator of Moon’s antics. He knew exactly what strings to pull, and he was a great foil for Moon’s humour, verbal and otherwise. And John, like you say, could just sit back and let it roll over him. John had a much wittier sense of humour, but he could get stuck in when the cake fights started and all that, a lot of fun. But I didn’t do too much of picking up the pieces, and in the end I just used to sit there like John. Even smashing up rooms gets boring after a while. It’s like anything in life, it’s really great the first time… but the second time? ‘It wasn’t as good as last time, we’ve got to work harder on this’. Then the third time: ‘Oh God, it’s lost a bit of its excitement’. And then – when you can afford it – it’s no fun at all.”

Life with Keith Moon was many things, but never dull. And the opening segment of The Kids Are Alright documents an incident that pretty much defines the perilous nature of co-existing in the same orbit as rock’s most celebrated madman.

Unimpressed by a half-cocked pyrotechnic rehearsal on American TV variety extravaganza The Smothers Brothers Show, Keith plied the man in charge of special effects with enough alcohol to persuade him to increase the explosive charge. When it went off, Pete’s hair caught fire, Roger was blown across the studio, and Keith ended up with a large chunk of drum-kit shrapnel embedded in his arm.

Was that the only occasion when Keith’s antics actually put your lives in danger?

“Well that was fucking serious,” smiles Daltrey, “Once, we chartered a plane to Germany. And as we were flying home he came out wearing the toilet door over his shoulder. He’d almost ripped the bulkhead of the fucking plane off. Which got us a bit nerve- racked. You suddenly realise that, hang about, a plane is built so that every bit of the structure holding it together is quite important, and ripping bits out in mid-flight is not a fucking good idea [laughs].”

Also included in The Kids Are Alright is priceless footage of The Who, especially Moon, doing to TV chat-show host Russell Harty almost exactly the same as Rod Hull’s Emu did to Michael Parkinson.

How drunk was Keith on that occasion?

“He wasn’t drunk. That was Keith. That’s how he was.”

But when he was in that kind of mood…

“What do you mean, ‘When he was in that kind of mood’? That’s how he was. He was like that 24⁄7. Well, he would have his down moments, but two or three hours out of every day that’s what he was like.”

He must have been bloody hard work.

“Fucking hard work. But fun… never dull. He was hard work, and I can’t pretend he wasn’t, but it’s the kind of hard work that’s pleasurable. And he was so creative, and he was so verbally astute. His use of language was way beyond his education.”

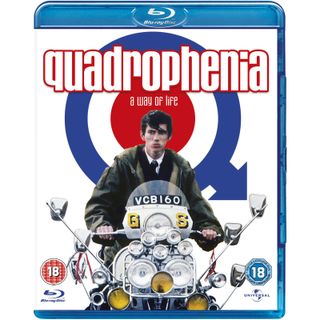

There’s no Quadrophenia material in The Kids Are Alright, and despite the fact that Franc Roddam’s classic 79 movie version of The Who’s 73 concept album was the catalyst for an all-pervasive cultural revolution in the shape of the second coming of mod, Quadrophenia seems to have always been overshadowed by Tommy.

“Well I don’t agree that it’s been overshadowed by it,” Daltrey says with a frown. “I think Quadrophenia has an audience that’s more attached to it than anyone is to Tommy. Although Tommy is probably more commercial, people in the Quadrophenia camp are more attached to it because it articulates a very important moment in their lives. Whether you’re today’s generation, 20 years ago’s generation or our generation, it articulates a specific area of your life that every adolescent goes through. And those people that discover Quadrophenia, and identify with it, attach it to themselves more strongly than anyone ever attached Tommy to themselves.”

Audiences in the punk era were able to equate everything that was happening on screen to their own life experience, in spite of the fact that the film was set at least a decade earlier. It was very much a case of same feelings, different tribe.

“That’s right, it’s just tribes. Tribal music. And of course the passions and feelings of adolescence will always be the same. It’s always a struggle for identity and: ‘Where the fuck do I go?’; ‘What’s the next step in life?’. And no matter how the circumstances around it might change – it might be scooters, it might be motorbikes, it might be flying fucking saucers – what is going on within the human being at that age is going to be the same.”

The Who without John Entwistle (whose sudden, drug-induced death in Las Vegas happened on the eve of the band’s 2002 American tour) seems almost inconceivable, but you got on and fulfilled your obligations with incredible resilience. It must have been extremely draining emotionally. Did you ever consider cancelling those shows in order to to lick your wounds?

“We did on the day we heard that John had died. We certainly did. But we considered everything. We considered how many people we would be letting down. It was a summer where there were very few sell-out tours in America; there was only us, McCartney and Springsteen selling out. We worked out how many people would be affected.

“We’d [the world] been in a depression, really. Politicians won’t tell you that, but it has certainly been a very strong recession, especially in America. And you gain responsibilities. We worked out that we were employing – when you take the car park attendants and everything else in all the venues around America – thousands of people, and that would have been one day where they would have been sitting on their arses not getting paid. And you think: ‘Fucking hell. We’ve got a bit of responsibility here. We can duck it quite easily. John’s dead, it’s the perfect time to stop, but maybe we should reconsider. Let’s see what we can do’.

“And Pete felt, and I do too, that it’s too easy at our age. We’ve always been a band that reflects what’s happening in our generation, and we’re unfortunately the next in line for the hole in the ground – fact of life.

“We owe it to our fans, our original fans that are our age now, to show them how to live. And you don’t fucking give up because one of your mates died, mate. You carry on. If you don’t feel you’ve got anything to offer, then by all means stop, but at the moment I feel we’ve still got a lot to offer. Pete’s writing new stuff now, I can still sing as good as I ever could, Pete’s one of the genius guitarists and songwriters of the last century, why not go on? It might not be the same, but it doesn’t make it irrelevant. We can still play the old stuff as good as we ever could, and although John isn’t playing it, nor is Keith – and Keith hasn’t been for 26 years. You hear it played without him and he lives within it.

“Music has got that ability to transcend life, and they’re the reasons we went on. And, believe it or not, it feels like we’ve still got all the best of what John brought to the band. Pino [Palladino, Entwistle’s replacement] doesn’t play like John played at all, but what Pino does play, and what is structured within the songs, reflects enough of what John did. So you get all the best of what John and Keith did but it’s opened up space where Pete and I can stretch out. And at this time in our life maybe we should be doing that and trying to find new avenues. It’s made it exciting and, like I say, it’s given us open roads to travel.”

And you say that the best work from The Who is yet to come.

“I’ve always felt that. I’ve always had a thing in my bones about what kind of writer Pete Townshend is. He’s a guy who writes about where he is in life, about the spiritual journey that a life is; he always has. He used to write great about adolescence. That’s only because that’s where he was then. But you have to get to a certain age before you can actually face the fact that you’re fucking going to get old and you’re the next in line for the graveyard. And when it comes to the point where he crosses that line, he will write about it in a way that it’s never been written about before, in a way that can communicate to everybody going through that period in their life in the same way that he communicated with adolescents. And I think from that point of view alone he’s got the potential to articulate it in a way that will make it his best piece of work, because nobody writes about that period of your life in music, not in pop music anyway.”

It’s uncharted territory, and it’s quite courageous to address it and face it head on.

“Well, I think it’s important that we do. I think the most important function of music is to reflect life itself, because to me it is the most important thing in life. A life without music is no life at all.”

Are you perfectly content to be, almost exclusively, an interpreter of Pete’s songs?

“Yeah.”

That’s it, period? But don’t you ever wish that you had persevered more with growing your solo career?

“Hobby.”

Don’t you ever wish you’d investigated your own songwriting potential more?

“I can write. I write all the time. I write songs that have been used in film soundtracks and things. But I’m not Pete Townshend. I was the lucky fucker who got to sing songs of pure genius, and I’m not moaning. And I’m very happy with that, thank you very much. I would like some of the publishing [laughs] but apart from that…”

On Quadrophenia Roger Daltrey sang the lead role of Jimmy Cooper: in popular culture terms the ultimate exemplification of the everyman mod ideal.

And The Who are more synonymous with the 60s mod scene than any other band. But did Daltrey ever actually consider himself to be a mod?

“No. Never. And if you read stuff from the period, I always made it painfully apparent that I was a fucking sheep in wolf’s clothing.”

And did you always consider the whole pop-art subtext attributed to The Who to be, and I quote, ‘a load of old bollocks’?

“No, I didn’t… But it was like not liking Elvis, wasn’t it? You had to say that it was a load of old bollocks, otherwise you’d have been considered totally pretentious. But I was very aware of the fact that we were living pop-art – you know, a manufactured thing. We were the Campbell’s soup tin; we were the Coke bottle. We were just another package; we were packaging music. That’s what we were doing. But if you had started to say that at that time, it would have seemed incredibly pretentious.”

It is bizarre that an entire generation, when faced with the RAF bullseye symbol, don’t consider the proud and enduring tradition of the Royal Air Force for a second. Instead their minds are irresistibly drawn to a T-shirt that Keith Moon favoured for a couple of months in 1966.

“People underestimate just how much, in terms of modern visual graphics, The Who put out there. The Union Jack on anything other than a flag was put out there by The Who. When we did that, the first Union Jack jacket, which was where it started, one Union Jack jacket, Kit Lambert [band co-manager] and Pete bought the flags and went into a tailor on Saville Row and said: ‘Will you make this into a jacket?’. ‘Can’t do that, sir, we’ll be put into prison’. We had to go to a backstreet tailor and get the bloody thing made, because they were really frightened of going to jail. That’s how serious it was then. To cut the flag was serious shit in those days. Now look at it. You can wipe your arse on the flag these days. And it was a similar thing with the bullseye T-shirt.”

- The Who release dazzling live version of Pinball Wizard

- Roger Daltrey: Rap is more relevant than rock

- Roger Daltrey: There's no music industry anymore, why would we make an album?

The Who did manage to hijack a number of cultural icons and make them their own: the white Levi jacket and the fringed suede jacket soon became known in popular street fashion parlance as the ‘Keith Moon’ and the ‘Roger Daltrey’ respectively.

“Well, when people write about the mod period, and they write about the fashions and you see the photographs, obviously those photographs represent just one day, or one hour, in the life of mod. And it’s very hard to get a perception of how the fashion used to change within the fucking week. It was scary how quickly it changed in those days. What would be fashionable one week would be out of fashion the next and there’d be something else. I mean, one week it was ice-cream jackets – three-quarter-length white jackets – and then it went to short ones, and they were there for like two weeks and gone. And if you were seen wearing them after that two weeks it was like: ‘Fucking hell, mate, where are you from? Wales?’ [laughs].”

What’s the most preposterous item of clothing you ever wore in the name of mod?

There follows a full 15 seconds of deafening silence. “I don’t think I ever wore anything that I wasn’t totally happy with. I mean, I think it got preposterous after the mod period when the flower-power thing came in. Now that was preposterous, that was fucking ridiculous [laughs]. But it was total bravado. When I think back to the things we used to wear, I was always wearing my girlfriend’s stuff.”

It has also become routine for chroniclers of street fashion to look back on old promo clips of The Who and reach the conclusion that ‘this is how mods dressed’. But before the arrival of The Who mods were all Italian suits and Hush Puppies shoes, and what has since become accepted as the classic mod look is actually the classic Who look.

“That’s right. But the classic mod look – the suits, the button-down shirts – it’s so classic it’ll never date. It’s sharp, pin-sharp, clean lines… sharp. Punk will never date, either, but in the opposite way – it’s totally flamboyant anarchy. We really just happened to be lucky. We were lucky to have arrived in just the right period. The bits inbetween were kind of boring though, weren’t they? I never got into the glam. I always found it embarrassing.”

We then discuss the glam-like dearth of good music in the present musical zeitgeist. And Daltrey is particularly interested in The Darkness: “Are they any good?” he asks. And, more specifically: “Could you put them on the same stage as Zeppelin and The Who?”. I venture the opinion that they’d make a bloody good support, but aren’t quite in the same league yet.

“There’s lots of Coldplay soundalikes at the moment, isn’t there?” he ventures without any enthusiasm, before sighing: “It’s weird.”

We’re in the doldrums because the industry seems far more interested in disposable pop.

“The industry is in trouble. The record companies are so stupid. They always were, nothing’s changed. They don’t want to admit that they were the ones that destroyed an art form, which was the album – the long-playing record. A total self-supporting art form – the artwork and the whole scale of it in people’s lives. It became very precious to people, and they replaced it with a plastic box that you can’t put any added value to. And you can copy what’s in the grooves. If you can do that for free, why fucking buy it? You don’t want the plastic box. You don’t really want them in your house, do you? They’re just nasty.”

Oh yeah, Roger Daltrey is definitely one of us. He would have made a magnificent punk.

This was first published in Classic Rock issue 58.

Pains, planes and automobiles: What happened when The Who took on America