From up here you can see the morning mist rising up off the freshly turned earth. The threads of sunshine are turning into beams of light. It’s cool, but the day’s going to swelter long before midday. In the distance the valley comes slowly into relief, the hill’s black edges stark against the blueing sky.

At this time of day, it’s deserted except for a figure leading two giant shire horses, hat pulled down hard on his head, doing his best to keep the two beasts with him, traversing the land in straight, parallel lines. A slow half‑circle turn and off they go again, this strange trio: mute, two of them hugely muscular, one sinewy and determined, working together.

In the distance, on the far edge of the field, a photographer cradling a camera with a telephoto lens shouts an instruction and the man between the horses jerks his head up, nods a silent affirmation, pulls at the heavy horses and goes again.

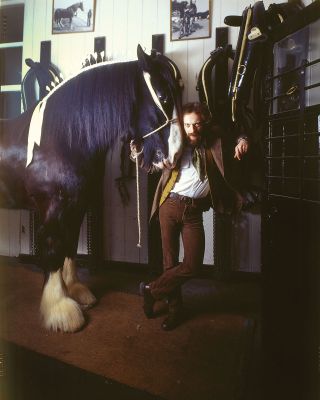

“I was holding on – they were very big!” Ian Anderson laughs as he remembers the day-long photo session for what would become the cover of Jethro Tull’s 1978 album Heavy Horses.

“They were actually pussycats, those two horses – they were very good. The absurdity was that the shots that were taken were from a very long way away. It could have been so much easier. They wanted to get the valley in the background and the brow of the hill to give it some context, so I was a long way off. I had to walk an awful long way with these animals!

“The photographer was way over there somewhere – there was a lot of hollering and shouting. And you had to walk, and then it would be, ‘Let’s do that again, sorry!’ But they were very well behaved. They were the best part of the day – they were nice animals.”

The band’s 11th studio album came as the decade was ending, a beautiful paean to a time that was fading as quickly as the 70s in which it was created. It’s framed, albeit loosely, as the spine of the band’s classic folk rock triumvirate, which began with 1977’s Songs From The Wood and ended with 1979’s Stormwatch. That’s to underplay its elegance and vivacity though.

It could be argued that Heavy Horses often gets overlooked simply for not being Songs From The Wood, an album that helped define Jethro Tull’s elongated musical and creative evolution. But that’s to miss the point. In the yearning and sometimes playful Heavy Horses, Anderson and his band might have been continuing with some of the familiar tropes of its predecessor, but the record’s hankering for a nearly bygone age – not least in the all‑encompassing title track – gives it a timeless, magical feel, like finding a trove of old, forgotten photographs.

“It was fairly hot on the heels of the Songs From The Wood album,” says Anderson today.

It’s early evening in London, but dark, the lights of passing cars rushing past the hotel bar’s windows. “In my mind, Heavy Horses is a logical successor – not quite part two, but it follows on with that slightly more rural context of its predecessor for a lot of the songs. I remember that Songs… was recorded in Morgan Studios, our last time there, and Heavy Horses was our first in the new Maison Rouge building, which we’d finished building in time to do the sessions.

“You have to remember, this was at the time punk’s final embers were burning out and you had bands like The Police and The Stranglers, who were, collectively speaking, a bunch of old hippies. The brave new world of punk rock had perhaps become commercialised at that point. But bands like those two used punk as a means to get their foot in the door, just as I did with the blues in 1968.

“So from our perspective then, it wasn’t that we were vindicated that this new, intrusive music form had somehow ousted us from the public eye and approval, it was just a parallel event. I don’t really recall being moved as a music maker by any of those changes in music that were going on. I knew what it was about and I rather liked some of it, but it was entirely separate to what I was writing. I didn’t want to try to catch up or be influenced by it. We were still making Jethro Tull albums at that point.”

Anderson wrote, as he always did, in snatched moments, some of the album’s songs created on the train between his studio in London and his then home in Buckinghamshire.

“I do remember writing on the train, yes,” he says. “In most cases the songs for Heavy Horses were written before we went into the studio, but sometimes they were written the night before, which is the way I often tend to work: writing things based on yesterday’s rehearsal. It will make me rethink something and come up with a new idea or even a new song. I wake up very early in the morning and I work quickly – that’s my time to get things done.”

The band worked in short, creative bursts in the Maison Rouge studio, Anderson laid low with a head cold for part of the sessions.

“I know some people have a lot of affection for the title track, but when I was recording that, I had a stinker of a cold and when I listen to the opening vocals in the quiet part of the song, I can hear the mucus and the congestion going on through my nose – it almost sounds like it was processed through something. Well, it was, in a way.”

So in the midst of decongestants, express trains between the capital and the countryside, and the final, faint traces of punk rock’s boom, how did Ian Anderson and Jethro Tull magic up the bucolic pastures of a green and pleasant land that was fast fading in the rear-view mirror of history?

“If I’m honest, I wrote the songs as they came,” says Anderson. “It wasn’t a concept album – I didn’t really have an overall thematic approach. It really was a collection of songs, albeit with a certain sense of tone and mood, and at the end of it, Heavy Horses was the one that presented itself somehow. It had this significance and it was a visual reference for the album cover. And it was also, let’s not pretend, quite a good title.

“That said, it’s unashamedly about something that was lamenting the passing of an age. It’s the equivalent of the end of the age of steam or when I do cathedral concerts at Christmas – it’s celebrating what’s possibly the end of our association with Christianity and the Anglican Church. Those things that you know aren’t going to be around very much longer, they do exercise an attraction and an appeal, emotionally and intellectually, because you’re having to chronicle something that you know other people are going to look back on and think, ‘What on earth was all that about? I’ve no idea what they were.’

“And that was the kind of thing that was happening with those kinds of horses. Before we released the album, the band had a brush with some heavy horses in terms of pre-publicity, where we went to a brewery to see the dray horses there. They weren’t using them as workhorses any more – it was more of a showbiz thing. They kept a few as draft horses for taking the beer, so it was still something they were keeping alive for the tourists and for tradition, but it wasn’t there for the daily deliveries any more.

“So I’d met some heavy horses before, and though we [Anderson and his wife] didn’t have heavy horses, we had a few horses around the place, so I was pretty comfortable being put in charge of those two monsters. That said, you have to remember that there had been various horses used in cultivation, but there were small, working horses, the pit ponies that pulled coal out of the ground. Working horses are not all necessarily of a larger stature, hence the album’s dedication to ‘indigenous working ponies and horses of Great Britain.’”

Even with its underpinning pastoral overtones, Anderson also found time to address the leaden travails of modern living in Journey Man, a song that surely must have been conjured up on the rattling rails leading from his country home into London.

The animal theme continues with nods to both Anderson’s dog and another Jethro Tull song about cats in the shape of …And The Mouse Police Never Sleep. Meanwhile, No Lullaby is guitarist Martin Barre in full flight, while Weathercock marries folk and hard rock to dizzying effect.

That said it’s still the title track that casts the longest shadow, and it’s a song that’s endured in the band’s live set, even with some minor tweaking.

“I changed it a few years ago,” says Anderson, “to bring some other elements into it. I changed some of the lyrics, which is a brave and perhaps silly thing to do, but I wanted to give a little bit more emphasis to put in context that world – I guess, being over 30 years later, it’s even less likely to encounter working horses. In fact, right at this moment, there’s a lot of pressure on the gene pool for a lot of rare breeds of horses, so it’s looking a bit rough for some of them as there are fewer people willing to look after them and so forth.

“The problem is that they’re not riding horses – you can’t hop on their back and go for a walk; they don’t race. They’re just an impediment, really, in terms of the fact that they need a lot of land to graze and need to be mucked out and looked after just like any other horse. It’s not their fault, but they can’t earn their living these days.

“So I thought it’d be nice just to bring in the context, so the second verse now starts with a reference to ‘nothing runs like a Deere’, which is the slogan for the famous John Deere tractors. I’m trying to make the more obvious comparison with today’s world where we talk in terms of horsepower, but today’s world is full of air-conditioned cabs and hydraulic seats and suspension. It’s a very different world, which was just beginning to happen when I got into farming.

“You know, I think there’s something to be said for people getting their hands dirty,” Anderson continues. “And I think, in a way, there’s something more romantic and, dare I say it, something more satisfying at the end of the day about humping bales of hay than humping Marshall cabinets into the back of a transit van. And you get cold and sore hands, but it’s good for the soul and it’s all tied in with that thing that along the way, and over the years, you’ve done something, be it farming or whatever.

“But the one thing is that you have to be prepared to get down and dirty and get wet and cold, get back to the earth, to a more traditional way of doing things.”

The field looks different now. The earth’s freshly turned, the sun high in the sky, but the figures are gone and a tractor idles in the distance, a thin plume of smoke, barely an outline, evaporating in the air.

At the farthest corner of the field stand a pair of heavy horses, indescribably tall, a towering monument to a time passed. Blink and the waves of heat from the earth make them into mirages out at the horizon and for a moment, you can’t be sure. You strain to see, but they’ve gone.

The Heavy Horses 40th Anniversary New Shoes Edition box set is out on March 2 via Parlophone. See www.jethrotull.com for details